|

100,000-year problem

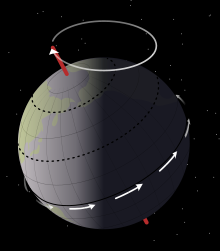

The 100,000-year problem (also 100 ky problem or 100 ka problem) of the Milankovitch theory of orbital forcing refers to a discrepancy between the reconstructed geologic temperature record and the reconstructed amount of incoming solar radiation, or insolation over the past 800,000 years.[1] Due to variations in the Earth's orbit, the amount of insolation varies with periods of around 21,000, 40,000, 100,000, and 400,000 years. Variations in the amount of incident solar energy drive changes in the climate of the Earth, and are recognised as a key factor in the timing of initiation and termination of glaciations. While there is a Milankovitch cycle in the range of 100,000 years, related to Earth's orbital eccentricity, its contribution to variation in insolation is much smaller than those of precession and obliquity. The 100,000-year problem refers to the lack of an obvious explanation for the periodicity of ice ages at roughly 100,000 years for the past million years, but not before, when the dominant periodicity corresponded to 41,000 years. The unexplained transition between the two periodicity regimes is known as the Mid-Pleistocene Transition, dated to some 800,000 years ago. The related 400,000-year problem refers to the absence of a 400,000-year periodicity due to orbital eccentricity in the geological temperature record over the past 1.2 million years.[2] The transition in periodicity from 41,000 years to 100,000 years can now be reproduced in numerical simulations that include a decreasing trend in carbon dioxide and glacially induced removal of regolith, as explained in more detail in the article Mid-Pleistocene Transition.[3] Recognition of the 100,000-year cycle The geologic temperature record can be reconstructed from sedimentary evidence. Perhaps the most useful paleotemperature indicator of past climate is the fractionation of oxygen isotopes, denoted δ18O. This fractionation is controlled mainly by the amount of water locked up in ice and the absolute temperature of the planet and has allowed a timescale of marine isotope stages to be constructed. By the late 1990s, δ18O records of air (in the Vostok ice core) and marine sediments were available and were compared with estimates of insolation, which should affect both temperature and ice volume. As described by Shackleton (2000), the deep-sea sediment record of δ18O "is dominated by a 100,000-year cyclicity that is universally interpreted as the main ice-age rhythm". Shackleton (2000) adjusted the time scale of the Vostok ice core δ18O record to fit the assumed orbital forcing and used spectral analysis to identify and subtract the component of the record that in this interpretation could be attributed to a linear (directly proportional) response to the orbital forcing. The residual signal (the remainder), when compared with the residual from a similarly retuned marine core isotope record, was used to estimate the proportion of the signal that was attributable to ice volume, with the rest (having attempted to allow for the Dole effect) being attributed to temperature changes in the deep water. The 100,000-year component of ice volume variation was found to match sea level records based on coral age determinations, and to lag orbital eccentricity by several thousand years, as would be expected if orbital eccentricity were the pacing mechanism. Strong non-linear "jumps" in the record appear at deglaciations, although the 100,000-year periodicity was not the strongest periodicity in this "pure" ice volume record. The separate deep sea temperature record was found to vary directly in phase with orbital eccentricity, as did the Antarctic temperature and CO2; so eccentricity appears to exert a geologically immediate effect on air temperatures, deep-sea temperatures, and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Shackleton (2000) concluded: "The effect of orbital eccentricity probably enters the paleoclimatic record through an influence on the concentration of atmospheric CO2".[4] Elkibbi and Rial (2001) identified the 100 ka cycle as one of five main challenges met by the Milankovitch model of orbital forcing of the ice ages.[5] Hypotheses to explain the problem As the 100,000-year periodicity only dominates the climate of the past million years, there is insufficient information to separate the component frequencies of eccentricity using spectral analysis, making the reliable detection of significant longer-term trends more difficult, although the spectral analysis of much longer palaeoclimate records, such as the Lisiecki and Raymo stack of marine cores[6] and James Zachos' composite isotopic record, helps to put the last million years in a longer-term context. Hence there is still no clear proof of the mechanism responsible for the 100 ka periodicity—but there are several credible hypotheses. Climatic resonanceThe mechanism may be internal to the Earth system. The Earth's climate system may have a natural resonance frequency of 100 ka; that is to say, feedback processes within the climate automatically produce a 100 ka effect, much as a bell naturally rings at a certain pitch.[7][8] Opponents to this claim point out that the resonance would have to have developed 1 million years ago, as a 100 ka periodicity was weak to non-existent for the preceding 2 million years. This is feasible—continental drift and sea floor spreading rate change have been postulated as possible causes of such a change.[9] Free oscillations of components of the Earth system have been considered as a cause,[10] but too few Earth systems have thermal inertia on a thousand-year timescale for any long-term changes to accumulate. The most common hypothesis looks to the Northern Hemisphere ice sheets, which might expand through a few shorter cycles until large enough to undergo a sudden collapse.[11] The 100,000-year problem has been scrutinized by José A. Rial, Jeseung Oh and Elizabeth Reischmann[12] who find that master-slave synchronization between the climate system's natural frequencies and the eccentricity forcing started the 100 ky ice ages of the late Pleistocene and explain their large amplitude. Orbital inclination Orbital inclination has a 100 ka periodicity, while eccentricity's 95 and 125ka periods could inter-react to give a 108ka effect. While it is possible that the less significant, and originally overlooked, inclination variability has a deep effect on climate,[13] the eccentricity only modifies insolation by a small amount: 1–2% of the shift caused by the 21,000-year precession and 41,000-year obliquity cycles. Such a big impact from inclination would therefore be disproportionate in comparison to other cycles.[9] One possible mechanism suggested to account for this was the passage of Earth through regions of cosmic dust. Our eccentric orbit would take us through dusty clouds in space, which would act to occlude some of the incoming radiation, shadowing the Earth.[13] In such a scenario, the abundance of the isotope 3He, produced by solar rays splitting gases in the upper atmosphere, would be expected to decrease—and initial investigations did indeed find such a drop in 3He abundance.[14][15] Others have argued possible effects from the dust entering the atmosphere itself, for example by increasing cloud cover (on 9 July and 9 January, when the Earth passes through the invariable plane, mesospheric cloud increases).[16] Therefore, the 100 ka eccentricity cycle can act as a "pacemaker" to the system, amplifying the effect of precession and obliquity cycles at key moments, with its perturbation.[17] Precession cyclesA similar suggestion holds the 21,636-year[failed verification] precession cycles solely responsible. Ice ages are characterized by the slow buildup of ice volume, followed by relatively swift melting phases. It is possible that ice built up over several precession cycles, only melting after four or five such cycles.[18] Dust and albedoIt has been suggested that ice-sheet albedo and dust are responsible. The high albedo of northern ice sheets will resist climatic warming from Milankovitch maxima unless they are covered in dust. Dust episodes occur just before each interglacial warming period, and it is claimed that the resulting reduced albedo of northern ice sheets assists in interglacial warming. Dust episodes are said to be caused by low atmospheric CO2 creating CO2-deserts in northern China upland areas, with the resulting dust creating the Loess Plateau and coating the northern ice sheets.[19] Solar luminosity fluctuationA mechanism that may account for periodic fluctuations in solar luminosity has also been proposed as an explanation. Diffusion waves occurring within the Sun can be modeled in such a way that they explain the observed climatic shifts on Earth.[20] Land vs. oceanic photosynthesis The Dole effect describes trends in δ18O arising from trends in the relative importance of land-dwelling and oceanic photosynthesizers. Such a variation is a plausible cause of the phenomenon.[21][22] Ongoing researchThe recovery of higher-resolution ice cores spanning more of the past 1,000,000 years by the ongoing EPICA project may help shed more light on the matter. A new, high-precision dating method developed by the team[23] allows better correlation of the various factors involved and puts the ice core chronologies on a stronger temporal footing, endorsing the traditional Milankovitch hypothesis, that climate variations are controlled by insolation in the northern hemisphere. The new chronology is inconsistent with the "inclination" theory of the 100,000-year cycle. The establishment of leads and lags against different orbital forcing components with this method—which uses the direct insolation control over nitrogen-oxygen ratios in ice core bubbles—is in principle a great improvement in the temporal resolution of these records and another significant validation of the Milankovitch hypothesis. An international climate modelling exercise (Abe-ouchi et al., Nature, 2013[24]) demonstrated that climate models can replicate the 100,000-year cyclicity given the orbital forcing and carbon dioxide levels of the late Pleistocene. The isostatic history of ice sheets was implicated in mediating the 100,000-year response to the orbital forcing. Larger ice sheets are lower in elevation because they depress the continental crust upon which they sit, and are therefore more vulnerable to melting. See alsoNotes

References

|