|

177th Rifle Division

The 177th Rifle Division was formed as an infantry division of the Red Army south of Leningrad in March 1941, based on the shtat (table of organization and equipment) of September 13, 1939. As Army Group North advanced on Leningrad the division, still incomplete, was rushed south to the Luga area. In mid-July it helped provide the initial resistance to the LVI Motorized Corps which set up the counterstroke at Soltsy, the first significant check of the German drive on Leningrad. In August the German offensive was intensified and the defenders of Luga were encircled and forced to escape northward, losing heavily in the process. A remnant of the 177th reached Leningrad, where it received enough replacements to again be marginally combat-effective. In October to was moved to the Neva River line as part of the Eastern Sector Operational Group. After briefly coming under command of 55th Army it was moved across Lake Ladoga to join 54th Army. It remained in this Army, as part of Volkhov Front, almost continuously until early 1944, serving west of the Volkhov River. It took part in the winter offensive that finally drove Army Group North away from Leningrad and earned a battle honor for the liberation of Lyuban, where part of it had been raised in 1941. Following this victory it was reassigned to 2nd Shock Army in Leningrad Front, and took part in the unsuccessful efforts to retake the city of Narva, before being removed to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command in April for further rebuilding and replenishment. It returned to the fighting front at the beginning of May in 21st Army facing Finland. At the outset of the final offensive against Finland it was in 23rd Army in the Karelian Isthmus. During this operation it advanced through the central part of the isthmus against determined Finnish resistance. The division remained facing Finland until early 1945, when it was moved to Latvia and spent the remainder of the war containing the German forces trapped in Courland, eventually assisting in clearing the region after the German surrender in May. It was moved to the Gorkii Military District in August, and was disbanded there in April 1946. FormationThe division was formed in March 1941 south of Leningrad. At the start of the German invasion it was still trying to complete its formation under direct command of Leningrad Military District. Its order of battle on June 22, 1941, was as follows:

Col. Ivan Stepanovich Ugryumov was assigned to command on March 24, but he was superseded on May 5 by Col. Andrei Fyodorovich Mashoshin. On May 25 the commander of Leningrad District, Lt. Gen. M. M. Popov, and his staff, had drafted a defense plan under which the 177th, along with the 191st and 70th Rifle Divisions, plus the 3rd Tank and 163rd Motorized Divisions of 1st Mechanized Corps, would remain under his direct command as a strategic reserve. Popov's plan was flawed by the assumption that the main threat to the city would come from Finland, and little was done to prepare for a German drive from the south. It was not until June 23 that Popov dispatched a deputy, Lt. Gen. K. P. Piadyshev, in that direction. This officer soon recommended that a line be established from Kingisepp to Luga to Lake Ilmen. However, severe shortages of materiel and manpower prevented any immediate action.[2] Defense of LeningradAfter its breakneck advance through the Baltic states, Army Group North began moving again early on July 9 from the Pskov and Ostrov regions. It was now 250km from Leningrad. In anticipation, on July 4 Army Gen. G. K. Zhukov ordered Popov to "immediately occupy a defense line along the Narva–Luga–Staraya Russa–Borovichi front." Popov officially formed the Luga Operational Group on July 6,[3] and as of July 10 it consisted of the 191st and 177th Divisions as well as the 1st Narodnoe Opolcheniye Division and four machine gun-artillery battalions.[4] By July 14 the Group had been considerably reinforced with the 41st Rifle Corps, 1st Mountain Rifle Brigade, two more Opolcheniye divisions, and other forces. Popov also placed the two tank divisions of 10th Mechanized Corps in Front reserve to provide armor support. The construction of the actual defense line had begun on June 29, using construction workers and civilians from Leningrad, although when the 177th arrived south of Luga itself on July 4 it was so incomplete that an additional 25,000 labourers had to mobilized. The 191st Division occupied the Kingisepp sector of the line. Meanwhile, the German advance from Pskov, while slower than through the Baltics due to rugged terrain and summer heat, was still gaining some 25km per day. The 111th Rifle Division, which had already taken heavy losses in fighting east of Pskov, fell back to support the 177th south of Luga. As the LVI Motorized Corps, under command of Gen. E. von Manstein, and backed by infantry of I Army Corps, advanced on the Novgorod axis it encountered unexpectedly stiff resistance.[5] Counterstroke at SoltsyThe 8th Panzer Division, in the vanguard, penetrated 30-40km along the Shimsk road and reached the town of Soltsy late on July 13. Here it was halted by spirited opposition from the 177th and the 10th Mechanized, skilfully exploiting the difficult terrain. By nightfall the panzers found themselves isolated from the 3rd Motorized Division to its left and the 3rd SS Totenkopf Division lagging in the rear.[6] Alert for opportunities to strike back, the STAVKA ordered a counterstroke against the overexposed German force. This was communicated to Marshal K. Ye. Voroshilov, who in turn directed 11th Army to attack along the Soltsy-Dno axis with two shock groups. The northern group consisted of the 10th Mechanized's 21st Tank Division and the two divisions of 16th Rifle Corps, with reinforcements. The southern group consisted of the three divisions of the 22nd Rifle Corps, and was to attack 8th Panzer from the east, with one division moving against the panzers' communication lines to the southwest. The assault, launched in oppressive 32 degree C summer heat and massive clouds of dust, caught 8th Panzer and 3rd Motorized totally by surprise. The two divisions were soon isolated from one another and 8th Panzer was forced to fight a costly battle in encirclement for four days. It also disrupted the German offensive plans by forcing 4th Panzer Group to divert 3rd SS from the Kingisepp and Luga axes to rescue the beleaguered panzer division. In his memoirs von Manstein wrote:

The Soltsy counterstroke cost 8th Panzer 70 of its 150 tanks destroyed or damaged and represented the first, albeit temporary, success achieved by Soviet forces on the path to Leningrad. It also cost the German command a precious week to regroup and resume the advance. However, the cost to the Soviet forces was high.[7] In response to a letter from the STAVKA dated July 15, Popov split the Luga Group into three separate and semi-independent sector commands on July 23, in addition to relieving and arresting Piadyshev for "dereliction of duty". The Luga Sector, under command of Maj. Gen. A. N. Astinin, was tasked with holding the Luga highway axis south of Leningrad. He was assigned the 177th, 111th, and 235th Rifle Divisions, 2nd Tank Division, the 1st Regiment of 3rd Narodnoe Opolcheniye Division, two machine gun - artillery battalions, and a battalion from the Leningrad Artillery School. At the same time Voroshilov's headquarters inspected the Luga Defense Line and determined it was utterly inadequate. It was recommended that further defenses be constructed closer to Leningrad, despite Voroshilov's objections, which were overruled by Stalin.[8] By the beginning of August the 177th, 111th and 235th had come under command of 41st Rifle Corps, still in the Luga Group.[9] Retreat to LeningradOn August 8 Hitler ordered that Army Group North be reinforced with large armored forces and air support in preparation for a final drive on the city. Two days later elements of LVI Motorized, supported by I and XXVIII Army Corps, advanced along the Luga and Novgorod axes toward the southern and southwestern approaches to Leningrad. The three Corps tore into and through the partially prepared defenses of the Luga Group and advanced on Krasnogvardeysk, while the 48th Army was forced out of Chudova and Tosno. These advances cut the line of communications to the Luga Group, which had to give up the town August 20. Fighting in encirclement, the nine Soviet divisions, including the 177th, had to cut their way out to the north and east in small parties, harried continually by the 8th Panzer, 4th SS, 269th and 96th Infantry Divisions conducting ongoing converging attacks on the Group from all sides. The German command estimated Red Army losses at 30,000 men, 120 tanks and 400 guns among the encircled forces.[10] As of September 1 the 235th was still in 41st Corps which was assigned to the Southern Operational Group of Leningrad Front, which had been formed on August 27 from part of Northern Front.[11] Remnants of the division took up positions near Pushkin, but by now the combined strength of the 235th, 177th Rifle and 24th Tank Divisions was no more than 2,000 men. On September 8 elements of Army Group North captured Shlisselburg, completing the land blockade of Leningrad.[12] Under the circumstances the 235th would be disbanded as part of an effort to rebuild the 177th over the next four weeks.[13] On October 10, Colonel Mashoshin left the division to take command of the 115th Rifle Division; he would lead three other divisions during the war and gained the rank of major general on September 25, 1943. He was replaced by Col. Grigorii Ivanovich Vekhin, who had been serving as acting commander of 70th Rifle Division. First Sinyavino OffensiveIn early October the 177th was assigned to the Eastern Sector Operational Group, formed by Maj. Gen. I. I. Fedyuninskii, the commander of Leningrad Front, from 55th Army and Front reserves. This Group consisted of five rifle divisions, two tank brigades and one battalion, and supporting artillery. It was intended to assault across the Neva River on a 5km-wide sector between Peski and Nevskaya Dubrovka, advance toward Sinyavino, and help encircle and destroy the German forces south of Shlisselburg in conjunction with 54th Army advancing from the east, effectively lifting the siege. German action preempted the Soviet attack, as they began a thrust toward Tikhvin on October 16. Nevertheless, the STAVKA insisted that the attack proceed as planned on October 20, but it made little progress. By October 23, Tikhvin was directly threatened, and the STAVKA lost its nerve. Fedyuninskii was moved to command of 54th Army, Lt. Gen. M. S. Khozin, took over Leningrad Front, and the Sinyavino offensive was officially cancelled on October 28.[14] Tikhvin CounteroffensiveTikhvin fell on November 8 to 12th Panzer Division, but it had been weakened by Soviet resistance, was vastly overextended, surrounded on three sides, and subject to minus 40 degree C. temperatures. Despite this, Hitler refused to sanction any retreat. The STAVKA now prepared for a wide-reaching counteroffensive, to involve 17 rifle divisions, two tank divisions, and one cavalry division. The series of attacks began on November 12. Previous to this the forces of Leningrad Front had been ordered to support the operations east of the Volkhov River. Khozin launched an attack on November 2 from the bridgehead at Moskovskaya Dubrova against the 96th Infantry but made little impression at the cost of heavy casualties. Supporting KV tanks had been unable to cross the river due to heavy losses of bridging equipment. A second attempt was set for overnight on November 9, now also targeting the 227th Infantry Division. A special shock group had been formed from select Narodnoe Opolcheniye volunteers backed by the 177th and went into action on November 11 along an axis toward the Gorodok No. 1 settlement, which had been turned into a strongpoint. The attack faltered after gaining a small lodgement on the western edge of the settlement.[15] On December 7 the German forces were still in Tikhvin, but the counteroffensive west of Moscow by Western Front had begun two days earlier, which rendered Hitler's notions of continuing an advance from the town utterly futile. At 0200 hours on December 8 he finally authorized a withdrawal, which, in fact, had been underway for several hours. The retaking of Tikhvin, in the event, would prove to be one of the first permanent liberations of Soviet territory during the war, and probably saved Leningrad. By the end of the month Army Group North had been driven back roughly to the line of the Volkhov.[16] Also during December the 177th came under direct command of 55th Army,[17] and on December 18 Colonel Vekhin left the division; he would soon be given command of the 152nd Rifle Division and would end the war leading the 350th Rifle Division, becoming a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 29, 1945. He was replaced by Col. Anatolii Gavrilovich Koziev, who had previously led the artillery group of 42nd Army. Move to Volkhov FrontIn January 1942 the division left Leningrad via the Road of Life over Lake Ladoga to join 54th Army, which was still in Leningrad Front. With one brief interruption it was in this Army until February 1944, part of Volkhov Front.[18] 54th Army controlled the Lake's southern shore.[19] Lyuban Offensive Operation Having liberated the territory occupied by the Germans in their Tikhvin offensive and caused them significant casualties, Stalin expected his armies to be able to break the siege of Leningrad, as part of a series of offensives across the front. Army Gen. K. A. Meretskov of Volkhov Front wrote:

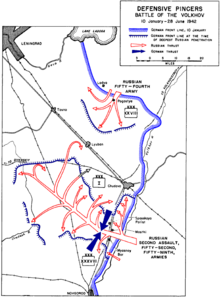

The new offensive had been launched by 54th Army on January 4, when it once again attacked I Corps, to the west of Kirishi. Forty-eight hours of heavy fighting produced an advance of only 4–5km, after which a counterattack by 12th Panzer Division drove the Army's troops back to their starting line. The attack was renewed on January 13 and the village of Pogoste was taken on the 17th, but that was the limit of success.[21] By mid-February 2nd Shock Army of Volkhov Front had driven across that river and was forcing its way through the swamps towards Lyuban, well in the German rear, but was unable to break out decisively toward Leningrad. On February 26, Leningrad Front received the following:

Reinforcement of 54th Army with the 4th Guards Rifle Corps made it possible to penetrate the German defenses near Pogoste on March 15, driving 22km southwards to within 10km of Lyuban, but German re-deployments brought the advance to a halt by March 31. The 177th was not heavily involved in this operation, holding the line on quieter sectors.[23] During March it was transferred to 8th Army, still in Leningrad Front, but returned to the 54th in April.[24] The 54th Army, while liberating some territory, was not successful in linking up with 2nd Shock Army, and the latter army was cut off and destroyed during the following months. Operation Polyarnaya Zvezda54th Army was engaged in mostly local fighting through the balance of 1942. It became part of Volkhov Front when it was formed in June.[25] The 177th was kept at a fairly low strength level on this defensive front. On January 12, 1943, Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts launched Operation Iskra, which by the end of the month had finally opened a land corridor to the besieged city, but this also did not directly involve the 54th. However, the success of Iskra, as well as the encirclement and destruction of German 6th Army at Stalingrad and the subsequent offensives in the south, led the STAVKA to plan a larger operation near Leningrad, to be called Operation Polyarnaya Zvezda (Pole Star), with the objective of the complete destruction of Army Group North.[26] The objective of 54th Army was to create a shallow encirclement, in conjunction with 55th Army from Leningrad, of the German forces still holding the Sinyavino – Mga area. The Army was to attack north of the village of Smerdynia in the direction of Tosno where it would meet the 55th; it would then attack towards Lyuban to divert the attention of German 18th Army from the deep encirclement being planned by Northwestern Front once its forces captured the Demyansk salient and its defenders. The 54th was reinforced before the offensive, which it began on February 10. It attacked the 96th Infantry with four rifle divisions (not including the 177th), three rifle brigades, and the 124th Tank Brigade, and yet only managed to penetrate 3–4km on a 5km front in three days of heavy fighting. On February 27, STAVKA ordered Pole Star halted, as almost no progress had been made on any sector.[27] Leningrad–Novgorod OffensiveThe front went back to relative inactivity for the remainder of 1943. At the beginning of October, after nearly two years of intermittent pressure, Army Group North evacuated the Kirishi salient to free up desperately needed reserves. In spite of this, the Army Group was in a very precarious position as the northern Soviet Fronts began planning a winter offensive. The plan that was issued to the commander of 54th Army between October and December must have looked familiar: a drive westwards towards Tosno, Lyuban and Chudovo as part of a short encirclement, followed by an advance southwest to Luga. However, in the past year the German forces had grown weaker, the Soviets stronger, and the offensive would be launched on three attack axes.[28] On December 18 Colonel Koziev was transferred to command of the 256th Rifle Division where he would remain for the duration, being made a Hero of the Soviet Union on February 21, 1944 and promoted to the rank of major general on June 3. He was replaced by Col. Aleksei Yakovlevich Tzygankov, who had previously led the 1st Mountain Rifle Brigade.  The offensive on first two of the attack axes, from Leningrad itself and from the Oranienbaum bridgehead, began on January 14. 54th Army launched the third prong on the 16th:

Although the attack had only advanced 5km by January 20, it was preventing German XXXVIII Army Corps from transferring forces to even harder-pressed sectors. In response to increased German resistance the 119th Rifle Corps was assigned to 54th Army, which resumed its advance overnight on January 25/26, captured Tosno and Ushaki, and reached the rail line southeast of Lyuban. The next day the commander of German 18th Army ordered his 121st Infantry Division, along with the Spanish Legion, to abandon the town, which was enveloped on three sides, and fall back to Luga. Fearing full encirclement after the loss of Lyuban and Chudovo the XXVIII Corps accelerated toward Luga, with 54th Army in pursuit.[29] On January 28 the division received a battle honor:

At the beginning of February the division was under direct command of Volkhov Front, but by a month later it had joined 124th Rifle Corps of 2nd Shock Army,[31] which was facing the German positions at Narva. First Battle for Narva2nd Shock, now under command of General Fedyuninskii, had initially made good progress toward Narva. Kingisepp had been liberated on February 1, and bridgeheads across the Narva River had been forced both north and south of the city by February 3. Beginning on February 11, Fedyuninskii's forces attacked the left wing forces of 18th Army in an effort to outflank the Panther Line from the north and to advance into Estonia. While the advance from the southern bridgehead gained up to 12km by mid-month it then came to a standstill. The STAVKA issued a directive to the commander of Leningrad Front, Army Gen. L. A. Govorov, late on February 14 demanding that Narva be taken no later than February 17. The 124th Corps had already been sent to 2nd Shock from Front reserves and it was duly deployed into the southern bridgehead, along with additional armor. Despite heavy fighting and consequent casualties on both sides by February 28 it was clear that the offensive had failed.[32] The next day Colonel Tzygankov left the 177th, being replaced by Col. Vasilii Mikhailovich Rzhanov. This officer would be promoted to the rank of major general on April 20, 1945 and would lead the division into the postwar. Continuation WarDuring March the 124th Corps returned to Leningrad Front reserves, and on April 6 entered the Reserve of the Supreme High Command for rebuilding, being assigned to 21st Army on April 10.[33] While the Leningrad–Novgorod offensive had driven Army Group North from the gates of Leningrad, Finland continued to hold the part of the Karelian Isthmus that it had retaken in 1941. The STAVKA, now with an abundance of resources, set a priority on defeating the Finnish forces in Karelia, reoccupying the territory taken after the Winter War, possibly occupying Helsinki, but in any case driving Finland out of the war. The USSR officially published its peace terms on February 28, but these were rejected on March 8. Although negotiations continued, the STAVKA began planning for operations in May.[34] At this time the line from Lake Ladoga to the Gulf of Finland was held by 23rd Army. It faced the six infantry and one armored divisions of the Finnish III and IV Army Corps, a total of roughly 250,000 personnel. 23rd Army had numerical superiority, especially in equipment, but also faced heavy fortifications and difficult terrain. In order to provide General Govorov with an overwhelming force to guarantee success, on April 28 the headquarters of 21st Army, under Lt. Gen. D. N. Gusev, arrived from the Reserve of the Supreme High Command, soon followed by the men and equipment of his 124th and 97th Rifle Corps. By this time 124th Corps comprised the 177th, 281st, and 286th Rifle Divisions.[35] During May the 177th and 281st were transferred to 23rd Army, joining the 372nd Rifle Division in 98th Rifle Corps.[36] Vyborg–Petrozavodsk OffensiveAt the outset of the offensive the 177th and 281st Divisions were deployed in the second echelon of 23rd Army,[37] in the eastern half of the Karelian Isthmus. In the plan for the offensive the entire 98th Corps, under command of Maj. Gen. A. I. Anisimov, would be handed over to join battle in the sector of 21st Army's right flank.[38]  On the evening of June 9 the first echelon rifle corps of 21st Army fired a 15-minute artillery preparation, followed by a reconnaissance-in-force to assess the damage. The offensive proper by this Army began at 0820 hours on June 10, following a 140-minute artillery onslaught. The 30th Guards Rifle Corps gained up to 15km against the 10th Infantry Division, while 97th Corps only managed to advance 5km. Meanwhile, the Finns were ordered to pull back to their second line. For the next day, 97th Corps was ordered to continue to advance on Kallelovo, and 98th Corps joined the offensive in the early morning, striking at the junction between 30th Guards and 97th Corps, which was handed over to 23rd Army at 1500 hours. By day's end the 97th and 98th Corps reached the Termolovo-Khirelia line. On June 12, 98th Corps advanced northward on the road to Siiranmiaki, but the pace of the advance was slowing, and it became clear that a regrouping would be necessary before tackling that second line.[39] Between June 14–17 the two Soviet armies penetrated the second Finnish defense line and began a pursuit towards the third. This began with a 55-minute artillery preparation on the 23rd Army sector and the Army went over to the attack at 1000 hours along the Keksholm axis. On the left flank the 98th Corps, with two divisions of 115th Rifle Corps, attacked the defenses of 2nd and 15th Infantry Divisions in the sector of Lake Lembalovskoe and Kholttila. This force managed to capture the strongpoints of Vekhmainen and Siiranmiaki, 500-600m into the second Finnish defensive belt, by the end of the day. The attacks continued during June 16-17, but Finnish resistance increased with the commitment of scant reserves. 23rd Army slowed to a crawl in dense terrain where the Finns carried out skilful rearguard actions, and 98th Corps was completely stymied in attacks on many strongpoints in the second defensive belt. Govorov's orders on the afternoon of June 17 stated in part:

He also ordered both armies to create strong forward detachments reinforced with tanks and artillery. During the day the Army regained its momentum as the Finns fell back to the VTK line, advancing 5-10km on a 30km-wide sector against heavy resistance; 98th Corps reached the line from Iulentelia to Kakhkala to Tarpila. Despite these successes, both Govorov and the STAVKA considered that the advance was far too slow.[40] 23rd Army was now reinforced with 6th Rifle Corps, and fought all day on June 18 to pierce the VTK line. By dusk it had gained 15-20km, reaching a line from the mouth of the Taipalen-ioki River on Lake Ladoga to Marianiemi and as far as Kaurula. The next day, 21st Army tore a huge gap in the defenses from Muolaa to the Gulf of Finland and began racing toward Vyborg. By now the depleted 2nd and 15th Infantry Divisions, reinforced by 19th Infantry Brigade, were trying to hold sectors up to 50km wide. Overnight on June 19/20, Govorov ordered the two armies to "destroy the enemy Vyborg grouping and capture Vyborg no later than 20 June by developing the attack to the northwest." 23rd Army was to attack from the line Kiuliapakkola–Kheinioki with the 6th and 98th Corps to reach a line from Kavantsaari Station to Kukauppi no later than June 21.[41] At the same time the 177th was transferred to 6th Corps,[42] and it captured the Saren Peninsula on June 27 before going over to the defense. On July 10 it returned to 98th Corps, which was now part of 21st Army.[43] During the offensive the division suffered 1,177 fatal casualties, of which 95 were officers, and 1,082 other ranks. Courland Pocket and PostwarIn September the 177th was reassigned to the 43rd Rifle Corps in 59th Army, still in Leningrad Front. In November it returned to 23rd Army as part of 97th Corps, which also contained the 178th and 327th Rifle Divisions.[44] It would remain under these commands until the German surrender.[45] In the spring of 1945 it moved into Latvia, eventually to the vicinity of Liepāja. On the evening of May 9, Army Group Courland surrendered, and for most of the remainder of the month the 177th was involved in taking the surrender of German troops. In August the 97th Corps was moved to the newly-formed Gorkii Military District, where the division was stationed at Ivanovo. It was disbanded there in April 1946.[46] ReferencesCitations

Bibliography

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||