|

Aboriginal Victorians

Aboriginal Victorians, the Aboriginal Australians of Victoria, Australia, occupied the land for tens of thousands of years prior to European settlement.[1] Aboriginal people have lived a semi-nomadic existence of fishing, hunting and gathering and associated activities for at least 40,000 years.[2] The Aboriginal people of Victoria had developed a varied and complex set of languages, tribal alliances, beliefs and social customs that involved totemism, superstition, initiation and burial rites, and tribal moieties.[3] History PrehistoryThere is some evidence to show that people were living in the Maribyrnong River valley, near present-day Keilor, about 40,000 years ago, according to Gary Presland.[4] At the Keilor archaeological site a human hearth excavated in 1971 was radiocarbon-dated to about 31,000 years BP, making Keilor one of the earliest sites of human habitation in Australia.[5] A cranium found at the site has been dated at between 12,000[6] and 14,700 years BP.[5] Similar archaeological sites in Tasmania and on the Bass Strait Islands have been dated to between 20,000 and 35,000 years ago, when sea levels were 130 metres (430 ft) below present level, allowing Aboriginal people to move across the region of southern Victoria and on to the land bridge of the Bassian plain to Tasmania by at least 35,000 years ago.[7][8] There is evidence of occupation in Gariwerd (the Grampians) – the territory of the Jardwadjali people – many thousands of years before the last Ice Age. One site in the Victoria Range (Billawin Range) has been dated from 22,000 years ago.[9][10] During the Ice Age about 20,000 years BP, the area now the bay of Port Phillip would have been dry land, and the Yarra and Werribee rivers would have joined to flow through the heads then south and south west through the Bassian plain before meeting the ocean to the west. Between 16,000 and 14,000 years BP the rate of sea level rise was most rapid, rising about 15 metres (50 ft) in 300 years according to Peter D. Ward.[11] Tasmania and the Bass Strait islands became separated from mainland Australia around 12,000 BP, when the sea level was about 50 metres (160 ft) below present levels.[7] Port Phillip was flooded by post-glacial rising sea levels between 8000 and 6000 years ago.[7] Oral history and creation stories from the Wada wurrung, Woiwurrung and Bun wurrung languages describe the flooding of the bay. Hobsons Bay was once a kangaroo-hunting ground. Creation stories describe how Bunjil was responsible for the formation of the bay,[8] or the bay was flooded when the Yarra River was created (Yarra Creation Story.[12]) LaterThe Wurundjeri mined diorite at Mount William Quarry, a source of the highly valued greenstone hatchet heads, which were and traded across a wide area as far as New South Wales and Adelaide. The mine provided a complex network of trading for economic and social exchange among the different Aboriginal nations in Victoria.[13][14][15] The quarry had been in use for more than 1,500 years and covered 18 hectares (44 acres), including pits of several metres. In February 2008 the site was placed on the National Heritage List for its cultural importance and archeological value.[16] In some areas semi-permanent huts were constructed and a sophisticated network of water channels were constructed for farming eels. During winter the Djab wurrung encampments were more permanent, sometimes consisting of substantial huts as attested by Major Thomas Mitchell near Mount Napier in 1836:

During early autumn there were often large gatherings of up to 1000 people for one to two months hosted at the Mount William swamp or at Lake Bolac for the annual eel migration. Several tribes attended these gatherings including the Girai wurrung, Djargurd wurrung, Dhauwurd wurrung and Wada wurrung. Near Mount William, an elaborate network of channels, weirs and eel traps and stone shelters had been constructed, indicative of a semi-permanent lifestyle in which eels were an important economic component for food and bartering, particularly the Short-finned eel.[18] Near Lake Bolac a semi-permanent village extended some 35 kilometres along the river bank during autumn. George Augustus Robinson on 7 July 1841 described some of the infrastructure that had been constructed near Mount William:

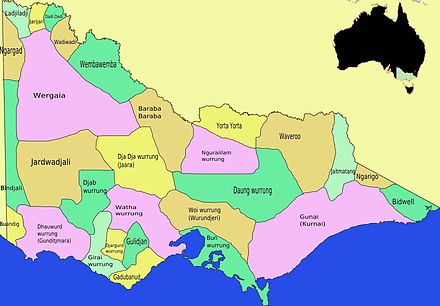

The way of life of the Aboriginal people of Western Victoria, who included the Gunditjmara, differed from other groups in Victoria in several respects. Because of the colder climate, they made, wore, and used as blankets, rugs of possum and kangaroo. They also built huts from wood and local basalt (known as bluestone), with roofs made of turf and branches.[20] The Budj Bim heritage areas, which show extensive evidence of fish-farming and traps for short-finned eels, around the Lake Condah area, are in Western Victoria.[21] Victorian Aboriginal languagesThirty nine Aboriginal languages were spoken in Victoria at the time of European contact, according to Ian D. Clark, although five of these languages are primarily located around the border areas with New South Wales and South Australia.[22] Clark also identified 19 sub-dialects in seven languages. The Victorian Aboriginal Corporation For Languages (VACL) is the peak body for Aboriginal languages in Victoria and coordinates all of the community language programs throughout Victoria. The corporation is focused on retrieving, recording and researching Aboriginal languages and providing a central resource on Victorian Aboriginal languages with programs and educational tools to teach the indigenous and wider community about language.[23] In recent years there has been an upsurge of interest in the Aboriginal languages of the south-eastern corner of Australia. The boundaries between one language area and another are not distinct. Rather, mixtures of vocabulary and grammatical construction exist in such regions, and so linguistic maps may show some variation about where one language ends and another begins. Many Australian indigenous languages have declined to a critical state. More than three-quarters of the original Australian languages have already been lost, and the survival of almost all of the remaining languages is extremely threatened. Communities throughout Victoria, supported by VACL, are reviving their languages through language camps, workshops, school programs, educational material for children, networking events, publications, music, digital resources, and dictionaries.[23] VACL is expanding into the use of interactive digital tools and apps for learning language. They have a number of digital applications to revive Victorian Aboriginal languages through traditional and contemporary stories.[24] VACL supports education and learning activities in schools and communities around Victoria.

Marginal language groups in Victorian border areas with South Australia and New South Wales include Bindjali, Buandig, Jabulajabula, Ngargad, and Thawa. There is considerable debate over the substance and location of North-eastern Victorian indigenous languages including Mogullumbidj, Dhudhuroa and Yaithmathang.[25] Howitt considered Mogullumbidj the easternmost dialect of the Kulin speaking tribes of central Victoria, but Clark argues the name is a descriptive term of appearance.[26] First Peoples' AssemblyIn November 2019, the First Peoples' Assembly was elected, consisting of 21 members elected from five different regions in the state, and 10 members to represent each of the state's formally recognised traditional owner corporations, excluding the Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation, who declined to participate in the election process. The main aim of the Assembly is to work out the rules by which individual treaties will be negotiated between the Victorian Government and individual Aboriginal peoples. It will also establish an independent "umpire" body to oversee the negotiations to ensure fairness.[27] The Assembly met for the first time on 10 December 2019[28] and again met over two days in February 2020. The Assembly hopes to agree upon a framework, umpire and process before November 2022, the date of the next state election.[29] See alsoReferencesNotes

Sources

Further reading

|