|

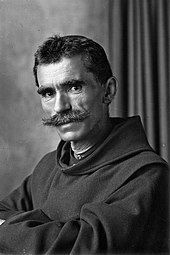

Albanian folkloreAlbanian folklore is the folk tradition of the Albanian people. Albanian traditions have been orally transmitted – through memory systems that have survived intact into modern times – down the generations and are still very much alive in the mountainous regions of Albania, Kosovo and western North Macedonia, as well as among the Arbëreshë in Italy and the Arvanites in Greece, and the Arbanasi in Croatia.[1] The most important artistic festival of Albanian folklore – the Gjirokastër National Folk Festival – takes place every five years at Gjirokastër Castle in Gjirokastër, southern Albania.[2] CollectionAlbanian traditions have been handed down orally across generations.[3] They have been preserved through traditional memory systems that have survived intact into modern times in Albania, a phenomenon that is explained by the lack of state formation among Albanians and their ancestors – the Illyrians, being able to preserve their "tribally" organized society. This distinguished them from civilizations such as Ancient Egypt, Minoans and Mycenaeans, who underwent state formation and disrupted their traditional memory practices.[4] Albanian traditional practices, beliefs, myths and legends have been sporadically described in written sources since the 15th century CE,[5][6][7] but the systematic collection of Albanian customs and folklore material began only in the 19th century.[8] Albanian collectors  Albanian myths and legends are already attested in works written in Albanian as early as the 15th century;[7] however, the systematic collection of Albanian folklore material began only in the 19th century.[8] One of the first Albanian collectors from Italy was the Arbëresh writer Girolamo De Rada who—already imbued with a passion for his Albanian lineage in the first half of the 19th century—began collecting folklore material at an early age. Another important Arbëresh publisher of Albanian folklore was the linguist Demetrio Camarda, who included in his 1866 Appendice al Saggio di grammatologia comparata (Appendix to the Essay on the Comparative Grammar) specimens of prose, and in particular, Arbëreshë folk songs from Sicily and Calabria, Albania proper and Albanian settlements in Greece. De Rada and Camarda were the two main initiators of the Albanian nationalist cultural movement in Italy.[9] In Greece, the Arvanite writer Anastas Kullurioti published Albanian folklore material in his 1882 Albanikon alfavêtarion / Avabatar arbëror (Albanian Spelling Book).[10] The Albanian National Awakening (Rilindja) gave rise to collections of folklore material in Albania in the second half of the 19th century. One of the early Albanian collectors of Albanian folklore from Albania proper was Zef Jubani. From 1848 he served as interpreter to French consul in Shkodra, Louis Hyacinthe Hécquard, who was very interested in, and decided to prepare a book on, northern Albanian folklore. They travelled through the northern Albanian mountains and recorded folkloric materials which were published in French translation in the 1858 Hécquard's pioneering Histoire et description de la Haute Albanie ou Guégarie (History and Description of High Albania or Gegaria"). Jubani's own first collection of folklore—the original Albanian texts of the folk songs published by Hécquard—was lost in the flood that devastated the city of Shkodra on 13 January 1866. Jubani published in 1871 his Raccolta di canti popolari e rapsodie di poemi albanesi (Collection of Albanian Folk Songs and Rhapsodies)—the first collection of Gheg folk songs and the first folkloric work to be published by an Albanian who lived in Albania.[11] Another important Albanian folklore collector was Thimi Mitko, a prominent representative of the Albanian community in Egypt. He began to take an interest in 1859 and started recording Albanian folklore material from the year 1866, providing also folk songs, riddles and tales for Demetrio Camarda's collection. Mitko's own collection—including 505 folk songs, and 39 tales and popular sayings, mainly from southern Albania—was finished in 1874 and published in the 1878 Greek-Albanian journal Alvaniki melissa / Belietta Sskiypetare (The Albanian Bee). This compilation was a milestone of Albanian folk literature being the first collection of Albanian material of scholarly quality. Indeed, Mitko compiled and classified the material according to genres, including sections on fairy tales, fables, anecdotes, children's songs, songs of seasonal festivities, love songs, wedding songs, funerary songs, epic and historical songs. He compiled his collection with Spiro Risto Dine who emigrated to Egypt in 1866. Dino himself published Valët e Detit (The Waves of the Sea), which, at the time of its publication in 1908, was the longest printed book in the Albanian language. The second part of Dine's collection was devoted to folk literature, including love songs, wedding songs, funerary songs, satirical verse, religious and didactic verses, folk tales, aphorisms, rhymes, popular beliefs and mythology.[12] The first Albanian folklorist to collect the oral tradition in a more systematic manner for scholarly purposes was the Franciscan priest and scholar Shtjefën Gjeçovi.[13] Two other Franciscan priests, Bernardin Palaj and Donat Kurti, along with Gjeçovi, collected folk songs on their travels through the northern Albanian mountains and wrote articles on Gheg Albanian folklore and tribal customs. Palaj and Kurti published in 1937—on the 25th anniversary of Albanian independence—the most important collection of Albanian epic verse, Kângë kreshnikësh dhe legenda (Songs of the Frontier Warriors and Legends), in the series called Visaret e Kombit (The Treasures of the Nation).[14][15] From the second half of the 20th century much research has been done by the Academy of Albanological Studies of Tirana and by the Albanological Institute of Prishtina. Albanian scholars have published numerous collections of Albanian oral tradition, but only a small part of this material has been translated into other languages.[10] A substantial contribution in this direction has been made by the Albanologist Robert Elsie. Foreign collectors Foreign scholars first provided Europe with Albanian folklore in the second half of the 19th century, and thus set the beginning for the scholarly study of Albanian oral tradition.[16] Albanian folk songs and tales were recorded by the Austrian consul in Janina, Johann Georg von Hahn, who travelled throughout Albania and the Balkans in the middle of the 19th century and in 1854 he published Albanesische Studien (Albanian Studies). The German physician Karl H. Reinhold collected Albanian folklore material from Albanian sailors while he was serving as a doctor in the Greek navy and in 1855 he published Noctes Pelasgicae (Pelasgian Nights). The folklorist Giuseppe Pitrè published in 1875 a selection of Albanian folk tales from Sicily in Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliani (Sicilian Fables, Short Stories and Folk Tales).[16][10] The next generation of scholars who became interested in collecting Albanian folk material were mainly philologists, among them the Indo-European linguists concerned about the study of the then little known Albanian language. The French consul in Janina and Thessalonika, Auguste Dozon, published Albanian folk tales and songs initially in the 1879 Manuel de la langue chkipe ou albanaise (Manual of the Shkip or Albanian Language) and in the 1881 Contes albanais, recueillis et traduits (Albanian Tales, Collected and Translated). The Czech linguist and professor of Romance languages and literature, Jan Urban Jarnik, published in 1883 Albanian folklore material from the region of Shkodra in Zur albanischen Sprachenkunde (On Albanian Linguistics) and Příspěvky ku poznání nářečí albánských uveřejňuje (Contributions to the Knowledge of Albanian Dialects). The German linguist and professor at the University of Graz, Gustav Meyer, published in 1884 fourteen Albanian tales in Albanische Märchen (Albanian Tales), and a selection of Tosk tales in the 1888 Albanian grammar (1888). His folklore material was republished in his Albanesische Studien (Albanian Studies). Danish Indo-Europeanist and professor at the University of Copenhagen, Holger Pedersen, visited Albania in 1893 to learn the language and to gather linguistic material. He recorded thirty-five Albanian folk tales from Albania and Corfu and published them in the 1895 Albanesische Texte mit Glossar (Albanian Texts with Glossary). Other Indo-European scholars who collected Albanian folklore material were German linguists Gustav Weigand and August Leskien.[16][10] In the first half of the 20th century, British anthropologist Edith Durham visited northern Albania and collected folklore material on the Albanian tribal society. She published in 1909 her notable work High Albania, regarded as one of the best English-language books on Albania ever written.[17] From 1923 onward, Scottish scholar and anthropologist Margaret Hasluck collected Albanian folklore material when she lived in Albania. She published sixteen Albanian folk-stories translated in English in her 1931 Këndime Englisht–Shqip or Albanian–English Reader.[18] Some Albanian folk traditions

Selected Albanian folk tales, legends, songs and balladsFolk tales

Myths and Legends

Songs and Ballads

See alsoReferences

Bibliography

Further reading

|