|

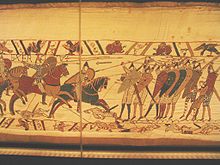

Anglo-Saxon warfare The period of Anglo-Saxon warfare spans the 5th century AD to the 11th in Anglo-Saxon England. Its technology and tactics resemble those of other European cultural areas of the Early Medieval Period, although the Anglo-Saxons, unlike the Continental Germanic tribes such as the Franks and the Goths, do not appear to have regularly fought on horseback.[1] EvidenceAlthough much archaeological evidence for Anglo-Saxon weaponry exists from the Early Anglo-Saxon period due to the widespread inclusion of weapons as grave goods in inhumation burials, scholarly knowledge of warfare itself relies far more on the literary evidence, which was only being produced in the Christian context of the Late Anglo-Saxon period.[2] These literary sources are almost all authored by Christian clergy, and thus do not deal specifically with warfare; for instance, Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People mentions various battles that had taken place but does not dwell on them.[3] Thus, scholars have often drawn from the literary sources from neighbouring societies, such as those produced by continental Germanic societies like the Franks and Goths, or later Viking sources.[4] As Underwood noted, "Warfare in the Anglo-Saxon period cannot be viewed as a uniform whole".[5] This is because Anglo-Saxon society changed greatly during this period; in the fifth century, it constituted an array of small tribal groups while by the eleventh it had consolidated into a single state.[5] Battlefield tacticsThere are extant contemporary descriptions of some Anglo-Saxon battles. Of particular relevance are the poems recounting the battles of Brunanburh, fought in 937 AD and Maldon, fought in 991 AD. In the literature, most of the references to weapons and fighting concern the use of javelins, spears and swords, with only occasional references to archery.[6] The shieldwall The typical battle involved both sides forming shieldwalls to protect against the launching of missiles, and standing slightly out of range of each other. Stephen Pollington has proposed the following sequence to a typical shieldwall fight[7]

Individual combat styleIndividual warriors would run forward from the ranks to gain velocity for their javelin throws. This made them vulnerable due to their being exposed, having left the protection of the shield wall, and there was a chance of being killed by a counter throw from the other side.[citation needed] This is epitomized in the following excerpt:

If a warrior was killed in the 'no man's land' between shieldwalls, someone from the other side might rush out to retrieve the valuable armour and weapons, such as extra javelins, sword, shield and so on from the corpse. The one best positioned to retrieve the body was often the thrower of the fatal javelin as he had run forward of his shield wall too in order to make his throw. Exposing himself like this, and even more so during his attempt to retrieve the slain's gear, was a great mark of bravery and could result in much valuable personal gain, not only in terms of his professional career as a retainer, but also in material wealth if the equipment were valuable.[citation needed] Due to the very visible and exposed nature of these javelin-throwing duels, we have some detailed descriptions which have survived, such as the following passage. The first part describes thrown javelin duels, and the latter part describes fighting over the corpses' belongings.

Reconstructions of fighting techniques suggested by Richard Underwood in his book Anglo Saxon Weapons and Warfare suggest two primary methods of using a spear. You can use it over arm – held up high with the arm extended and the spear pointing downwards. Used this way you could try and attack over the enemy shield against head and neck. Or you could use it underarm with the spear braced along the forearm. This was more defensive and was good for parrying the enemy spear and pushing against his shield to keep him away but was not much use offensively. Sometimes individuals or groups fighting over bodies might come to sword blows between the two shield walls. Ideally, enough damage would be done to the enemy through the launching of missiles, so that any shield-to-shield fighting would be a mopping-up operation rather than an exhausting and risky push back and forth at close quarters. At close quarters, swords and shields were preferred over thrusting spears. The shield was used to push the opponent in order to create a breach in the shield wall so that the opponent could become exposed to attack. Hacking through shields was a commonly used tactic, so having a strong sword arm and sword were of great benefit. The horse in war

There are numerous references to the horses of warriors in literature and graves with horse burials are known in the early Anglo-Saxon period. By the later period, much of the army may have travelled to war on horseback. There is little evidence of use of horses in battle, except in pursuit of a beaten foe. However, the Aberlemno 2 stone is thought to depict combat between Northumbrian cavalry and a Pictish army and the Repton stone shows a mounted warrior in a fighting pose.[8] After the Norman conquest of England the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine emperors became dominated by emigrant Anglo-Saxon warriors, to the extent of the guard becoming known in Greek as the Englinbarrangoi ("English-varangians"). In 1081 in the opening stages of the Battle of Dyrrachion the emperor Alexios I ordered the Varangians to dismount and march at the head of the army, an instance of Anglo-Saxons riding to battle but dismounting to fight.[9] Supplying warLittle is known about the way in which Anglo-Saxon armies were supplied. Smaller armies could live off the land but larger forces needed some degree of organised supply. It is possible that troops brought food with them on campaign but there is also limited evidence of the existence of pack horses tended by grooms being used to carry supplies and equipment.[10] Combined operations involving a fleet and army working together are recorded in the reign of Athelstan against the Scots and again in the 11th century in Wales. It is possible that, like later medieval operations in these areas, part of the role of the fleet was to carry supplies.[11] Training for warUnderstanding how battles were fought also helps us to understand why excelling in certain sports was considered the mark of a valuable retainer or war leader. Sports like running, jumping, throwing spears, and unbalancing people (i.e. wrestling) were all critical skills for combat.[12] Heroes like the legendary Beowulf are described as champions in such athletic events. See alsoReferencesFootnotes

Bibliography

Primary sourcesFurther reading

External links |