|

Art in Nazi Germany

The Nazi regime in Germany actively promoted and censored forms of art between 1933 and 1945. Upon becoming dictator in 1933, Adolf Hitler gave his personal artistic preference the force of law to a degree rarely known before. In the case of Germany, the model was to be classical Greek and Roman art, seen by Hitler as an art whose exterior form embodied an inner racial ideal.[1] It was, furthermore, to be comprehensible to the average man.[2] This art was to be both heroic and romantic.[2] The Nazis viewed the culture of the Weimar period with disgust. Their response stemmed partly from conservative aesthetics and partly from their determination to use culture as propaganda.[3] TheoryAs indicated by historian Henry Grosshans in his book Hitler and the Artists, Adolf Hitler who came to power in 1933 (quote): "saw Greek and Roman art as uncontaminated by Jewish influences. Modern art was [perceived by him as] an act of aesthetic violence by the Jews against the German spirit. Such was true to Hitler – wrote Grosshans – even though only Liebermann, Meidner, Freundlich, and Marc Chagall, among those who made significant contributions to the German modernist movement, were Jewish. But Hitler ... took upon himself the responsibility of deciding who, in matters of culture, thought and acted like a Jew."[4] The supposedly "Jewish" nature of art that was indecipherable, distorted, or that represented "depraved" subject matter was explained through the concept of degeneracy, which held that distorted and corrupted art was a symptom of an inferior race. By propagating the theory of degenerate art, the Nazis combined their anti-Semitism with their drive to control the culture, thus consolidating public support for both campaigns.[5] Their efforts in this regard were unquestionably aided by a popular hostility to Modernism that predated their movement.[6] The view that such art had reflected Germany's condition and moral bankruptcy was widespread, and many artists acted in a manner to overtly undermine or challenge popular values and morality.[7] In July 1937, two officially sponsored exhibitions opened in Munich: Entartete Kunst, (the Degenerate Art Exhibition), displayed modern art in a deliberately chaotic installation accompanied by defamatory labels that encouraged the public to jeer; in contrast, the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) made its premiere amid much pageantry. This exhibition, held at the palatial Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), displayed the work of officially approved artists such as Arno Breker and Adolf Wissel. "The audience entered the portals of the new museum, already dubbed "Palazzo Kitschi" and "Munich Art Terminal", to a stultifying display carefully limited to idealized German peasant families, commercial art nudes, and heroic war scenes, including not just a few works by jurist Ziegler himself."[8] "...The show was essentially a flop and attendance was low. Sales were even worse and Hitler ended up buying most of the works for the government."[8] At the end of four months Entartete Kunst had attracted over two million visitors, nearly three and a half times the number that visited the nearby Grosse deutsche Kunstausstellung.[9] Historical background The early twentieth century was characterized by startling changes in artistic styles. In the visual arts, such innovations as cubism, Dada and surrealism, following hot on the heels of Symbolism, post-Impressionism and Fauvism, were not universally appreciated. The majority of people in Germany, as elsewhere, did not care for the new art which many resented as elitist, morally suspect and too often incomprehensible.[10] During recent years, Germany had become a major center of avant-garde art. It was the birthplace of Expressionism in painting and sculpture, the atonal musical compositions of Arnold Schoenberg, and the jazz-influenced work of Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill. Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang's Metropolis brought expressionism to cinema. Creation of the Reichskulturkammer In September 1933, the Reichskulturkammer (Reich Culture Chamber) was established, with Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's Reichsminister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda) in charge.[11] Individual divisions in the Chamber of Culture for the Reich included: "press, radio, literature, movies, theater, music, and visual arts."[12] "The purpose of this chamber was to stimulate the Aryanization of German culture and to prohibit, for example, atonal Jewish music, the blues, surrealism, cubism, and Dadaism."[12] Nazi cultural policyBy 1935, the Reich Culture Chamber had 100,000 members.[13] Goebbels made clear that: "In the future only those who are members of the chamber will be allowed to be productive in our cultural life. Membership is open only to those who fulfil the entrance condition. In this way all unwanted and damaging elements have been excluded."[13] Nonetheless, there was, during the period 1933–1934, some confusion within the Party on the question of Expressionism. Goebbels and some others believed that the forceful works of such artists as Emil Nolde, Ernst Barlach and Erich Heckel exemplified the Nordic spirit; as Goebbels explained, "We National Socialists are not un-modern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters."[14] However, a faction led by Rosenberg despised Expressionism, leading to a bitter ideological dispute which was settled only in September 1934, when Hitler declared that there would be no place for modernist experimentation in the Reich. Document No. 2030-PS: Decree Concerning the Duties of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda of June 1933 stated that: "The Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda has jurisdiction over the whole field of spiritual indoctrination of the nation, of propagandizing the State, of cultural and economic propaganda, of enlightenment of the public at home and abroad; furthermore, he is in charge of the administration of all institutions serving these purposes".[15] This increased the jurisdiction of the Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda to include "enlightenment in foreign countries; art; art exhibitions; moving pictures and sport abroad" ... [and increased jurisdiction in domestic] "Press (including the Institute for Journalism); Radio; National anthem; German Library in Leipzig; Art; Music (including the Philharmonic Orchestra); Theater; Moving Pictures; Campaign against dirty and obscene literature" ... Propaganda for tourism." Signed by The Reich Chancellor, Adolf Hitler.[15] Document No. 2078-PS: Decree concerning the establishment of the Reichs Ministry of Science, Education and Popular Culture of 1 May 1934 stated that: "The Chancellor of the Reich will determine the various duties of the Reich Ministry for Science, Education, and Popular Culture."[16] Signed by The President of the Reich, von Hindenburg, and The Chancellor of the Reich, Adolf Hitler. Document No. 1708-PS: The program of the NSDAP stated that: only members of the German race can be citizens (Jews, specifically are denied citizenship), and that non-members of the race can only live in Germany as registered 'guests'. Point 23 stated: "We demand legal prosecution of artistic and literary forms which exert a destructive influence on our national life, and the closure of organizations opposing the above made demands.[17] Art theftNazis began plundering Jewish collections from 1933 in Germany with the Aryanization of Jewish art dealerships like that of Alfred Flechtheim and the transfer to non-Jewish owners.[18][19] In each country occupied by the Nazis, including Austria,[20] France,[21] Holland[22] and others, Jewish art collectors and art dealers were forced out of business and plundered as part of the Holocaust.[23] Later, as the occupiers of Europe, the Germans trawled the museums and private collections of Europe for suitably "Aryan" art to be acquired to fill a bombastic new gallery in Hitler's home town of Linz. At first a pretense was made of exchanges of works (sometimes with Impressionist masterpieces, considered degenerate by the Nazis), but later acquisitions came through forced "donations" and eventually by simple looting.[24] The purge of art in Germany and occupied countries was extremely broad. The Nazi theft is considered to be the largest art theft in modern history including paintings, furniture, sculptures, and anything in between considered either valuable, or opposing Hitler's purification of German culture.  During the Second World War, art theft by German forces was devastating, and the resurfacing of missing stolen art continues today, along with the fight for rightful ownership. Not only did the Reich confiscate and reallocate countless masterpieces from occupied territories during the war, but also put to auction a large portion of Germany's collection of great art from museums and art galleries. In the end, the confiscation committees removed over 15,000 works of art from German public collections alone.[25] It took four years to "refine" the Nazi art criteria; in the end what was tolerated was whatever Hitler liked, and whatever was most useful to the German government from the point of view of creating propaganda. A thorough head-hunting of artists within Germany was in effect from the beginning of the Second World War, which included the elimination of countless members within the art community. Museum directors that supported modern art were attacked; artists that refused to comply with Reich-approved art were forbidden to practise art altogether. To enforce the prohibition of practising art, agents of the Gestapo routinely made unexpected visits to artist's homes and studios. Wet brushes found during the inspections or even the smell of turpentine in the air was reason enough for arrest. In response to the oppressive restrictions, many artists chose to flee Germany.[26] Before the impending war and a time of simply looting occupied nation's art treasures, but during the Reich's efforts to free Germany of conflicting art, authorities of the Nazi party realized the potential revenue of Germany's own collection of art that was considered degenerate art which was to be purged from German culture. The Reich began to collect and auction countless pieces of art—for example, "on June 30, 1939 a major auction took place at the elegant Grand Hotel National in the Swiss resort town of Lucerne".[27] All of the paintings and sculptures had recently been on display in museums throughout Germany. This collection offered over 100 paintings and sculptures by numerous famous artists, such as Henri Matisse, Vincent van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso; all of which were considered "degenerate" pieces by Nazi authorities and were to be banished from Germany. An auction of this magnitude was viewed as suspicious by potential buyers, who feared that the profits would end up funding the Nazi party: "The auctioneer had been so worried about this perception that he had sent letters to leading dealers assuring them that all profits would be used for German museums".[28] In reality, all of the proceeds from the auction were deposited into "German controlled-accounts", and the museums "... as all had suspected, did not receive a penny".[29]  Genres Belief in a Germanic spirit—defined as mystical, rural, moral, bearing ancient wisdom, noble in the face of a tragic destiny—existed long before the rise of the Nazis; Richard Wagner celebrated such ideas in his work.[30] Beginning before World War I the well-known German architect and painter Paul Schultze-Naumburg's influential writings, which invoked racial theories in condemning modern art and architecture, supplied much of the basis for Adolf Hitler's belief that classical Greece and the Middle Ages were the true sources of Aryan art.[31] Among the well-known artists endorsed by the Nazis were the sculptors Josef Thorak and Arno Breker, and painters Werner Peiner, Arthur Kampf, Adolf Wissel and Conrad Hommel. In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich. The Great German Art Exhibition was designed to show works that Hitler approved of, depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealized soldiers and landscapes. The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art: modern, abstract, non-representational—or as the Nazis saw it, "degenerate". According to Klaus Fischer, "Nazi art, in short, was colossal, impersonal, and stereotypical. People were shorn of all individuality and became mere emblems expressive of assumed eternal truths. In looking at Nazi architecture, art, or painting one quickly gains the feeling that the faces, shapes, and colors all serve a propagandistic purpose; they are all the same stylized statements of Nazi virtues—power, strength, solidity, Nordic beauty."[32] Painting  Art of Nazi Germany was characterized by a style of Romantic realism based on classical models. While banning modern styles as degenerate, the Nazis promoted paintings that were narrowly traditional in manner and that exalted the "blood and soil" values of racial purity, militarism, and obedience. Other popular themes for Nazi art were the Volk at work in the fields, a return to the simple virtues of Heimat (love of homeland), the manly virtues of the National Socialist struggle, and the lauding of the female activities of child bearing and raising symbolized by the phrase Kinder, Küche, Kirche ("children, kitchen, church"). In general, painting—once purged of "degenerate art"—was based on traditional genre painting.[3] Titles were purposeful: "Fruitful Land", "Liberated Land", "Standing Guard", "Through Wind and Weather", "Blessing of Earth", and the like.[3] Hitler's favorite painter was Adolf Ziegler and Hitler owned a number of his works. Landscape painting featured prominently in the Great German Art exhibition.[33] While drawing on German Romanticism traditions, it was to be firmly based on real landscape, Germans' Lebensraum, without religious moods.[34] Peasants were also popular images, reflecting a simple life in harmony with nature.[35] This art showed no sign of the mechanization of farm work.[36] The farmer labored by hand, with effort and struggle.[37] Not a single painting in the first exhibition showed urban or industrialized life, and only two in the exhibition in 1938.[38] Nazi theory explicitly rejected "materialism", and therefore, despite the realistic treatment of images, "realism" was a seldom used term.[39] A painter was to create an ideal picture, for eternity.[39] The images of men, and still more of women, were heavily stereotyped,[40] with physical perfection required for the nude paintings.[41] This may have been the cause of there being very few anti-Semitic paintings; while such works as Um Haus and Hof, depicting a Jewish speculator dispossessing an elderly peasant couple exist, they are few, perhaps because the art was supposed to be on a higher plane.[42] Explicitly political paintings were more common but still very rare.[33] Heroic imagery, on the other hand, was common enough to be commented on by a critic: "The heroic element stands out. The worker, the farmer, the soldier are the themes .... Heroic subjects dominate over sentimental ones".[43] With the advent of war, war paintings became far more common.[44] The images were romanticized, depicting heroic sacrifice and victory.[45] Still, landscapes predominated, and among the painters exempted from war service, all were noted for landscapes or other pacific subjects.[46] Even Hitler and Goebbels found the new paintings disappointing, although Goebbels tried to put a good face on it with the observation that they had cleared the field, and that these desperate times drew many talents into political life rather than cultural.[47] In a speech at the Great German Art Exhibition in Munich Hitler said in 1939:

By 1938, nearly 16,000 works by German and non-German artists had been seized from German galleries and either sold abroad or destroyed.[49] Sculpture The monumental possibilities of sculpture offered greater material expression of the theories of Nazism. The Great German Art Exhibition promoted the genre of sculpture at the expense of painting.[50] As such, the nude male was the most common representation of the ideal Aryan; the artistic skill of Arno Breker elevated him to become the favourite sculptor of Adolf Hitler.[51][52] Josef Thorak was another official sculptor whose monumental style suited the image Nazi Germany wished to communicate to the world.[53] Nude females were also common, though they tended to be less monumental.[54] In both cases, the physical form of the ideal Nazi man and woman showed no imperfections.[41] MusicMusic was expected to be tonal and free of jazz influence; films and plays were censored. "Musical fare alternated between light music in the form of folk songs or popular hits (Schlager) and such acceptable classical music as Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Italian Opera."[55] Germany's urban centers in the 1920s and '30s were buzzing with jazz clubs, cabaret houses and avant-garde music. In contrast, the Nazi regime made concentrated efforts to shun modern music (which was considered degenerate and Jewish in nature) and instead embraced classical German music. Highly favored was music which alluded to a mythic, heroic German past such as Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven and Richard Wagner. Anton Bruckner was highly favored, as his music was regarded as an expression of the zeitgeist of the German volk.[56] The music of Arnold Schoenberg (and atonal music along with it), Gustav Mahler, Felix Mendelssohn and many others was banned because the composers were Jewish or of Jewish origin.[57] Paul Hindemith fled to Switzerland in 1938,[58] rather than fit his music into Nazi ideology. Some operas of Georg Friedrich Händel were either banned outright for themes sympathetic to Jews and Judaism or had new librettos written for them. German composers who had their music performed more often during the Nazi period were Max Reger and Hans Pfitzner. Richard Strauss continued to be the most performed contemporary German composer, as he had been prior to the Nazi regime. However, even Strauss had his opera The Silent Woman banned in 1935 due to his Jewish librettist Stefan Zweig.[59] Music by non-German composers was tolerated if it was classically inspired, tonal, and not by a composer of Jewish origin or having ties to ideologies hostile to the Nazi regime. The Nazis recognized Franz Liszt for having German origin and fabricated a genealogy that purported that Frédéric Chopin was German. The Nazi Governor-General of occupied Poland even had a "Chopin Museum" built in Kraków. Music of the Russian Peter Tchaikovsky could be performed in Nazi Germany even after Operation Barbarossa. Operas by Gioacchino Rossini, Giuseppe Verdi and Giacomo Puccini got frequent play. The most-performed modern non-German composers prior to the outbreak of war were Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Jean Sibelius and Igor Stravinsky.[59] After the outbreak of war, the music of German allies became more often performed, including the Hungarian Béla Bartók, the Italian Ottorino Respighi and the Finn Jean Sibelius. Composers of enemy nations (such as Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky) were largely banned and almost never performed – although there were some exceptions. There has been controversy over the use of certain composers' music by the Nazi regime, and whether that implicates the composer as implicitly Nazi. Composers such as Richard Strauss,[60] who served as the first director of the Propaganda Ministry's music division, and Carl Orff have been subject to extreme criticism and heated defense.[61] Jews were quickly prohibited from performing or conducting classical music in Germany. Such conductors as Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter, Ignatz Waghalter, Josef Krips, and Kurt Sanderling fled Germany. Upon the Nazi seizure of Czechoslovakia, the conductor Karel Ančerl was blacklisted as a Jew and was sent in turn to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Musicologists of Nazi GermanyAs the Nazi regime accrued power in 1933, musicologists were directed to rewrite the history of German music in order to accommodate Nazi mythology and ideology. Richard Wagner and Hans Pfitzner were now seen as composers who conceptualized a united order (Volksgemeinschaft) where music was an index of the German community. In a time of disintegration, Wagner and Pfitzner wanted to revitalize the country through music. In a book written about Hans Pfitzner and Wagner, published in Regensburg in 1939 followed not only the birth of contemporary musical parties, but also of political parties in Germany. The Wagner-Pfitzner stance contrasted ideas of other notable artists, such as Arnold Schoenberg and Theodor W. Adorno, who wanted music to be autonomous from politics, Nazi control and application. Although Wagner and Pfitzner predated Nazism, their sentiments and thoughts, Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk, were appropriated by Hitler and his propagandists—notably Joseph Goebbels. According to Michael Meyer, "The very emphasis on rootedness and on tradition music underscored Nazi understanding of itself in a dialectic terms: old gods were mobilized against the false values of the immediate past to offer legitimacy to the epiphany of Adolf Hitler and the music representation of his realm."[citation needed] Composers, librettists, educators, critics, and especially musicologists, through their public statements, intellectual writings, and journals contributed to the justification of a totalitarian blueprint to be implanted through nazification. All music was then composed for the occasions of Nazi pageantries, rallies, and conventions. Composers dedicated so called 'consecration fanfares,' inaugurations fanfares and flag songs to the Fuhrer. When the Fuhrer assumed power the Nazi revolution was immediately expressed in musicological journalism. Certain progressive journalism pertaining to modern music was purged. Journals that had been sympathetic to the ‘German viewpoint,’ entrenched in Wagnerian ideals, like the Zeitschrift für Musik and Die Musik, showed confidence in the new regime and affirmed the process of intertwining government policies with music. Joseph Goebbels used the Völkischer Beobachter, a journal that was disseminated to the general public in addition to elites and party officials, as an organ of Reich Culture. By the end of the 1930s the Mitteilungen der Reichsmusikkammer became another prominent journal that reflected the music policy, organizational and personnel changes in musical institutions. In the early years of Nazi rule, the musicologists and musicians redirected the orientation of music, defining what was "German Music" and what was not. Nazi ideology was applied to the evaluation of musicians for hero status; musicians defined in the new German musical era were given titles of prophets, while their accomplishments and deeds were seen as direct accomplishments of the Nazi regime. The contribution of German musicologists led to the justification of Nazi power and a new German music culture in whole. The musicologists defined the greater German values that musicians would have to identify with, because their duty was to integrate music and Nazism in way that made them look inseparable. Nazi myth making and ideology was forced upon the new musical path of Germany rather than truly embedded in the rhetoric of German music. Graphic design The poster became an important medium for propaganda during this period. Combining text and bold graphics, posters were extensively deployed both in Germany and in the areas occupied. Their typography reflected the Nazis' official ideology. The use of Fraktur was common in Germany until 1941, when Martin Bormann denounced the typeface as "Judenlettern" and decreed that only Roman type should be used.[62] Modern sans-serif typefaces were condemned as cultural Bolshevism, although Futura continued to be used owing to its practicality.[63] Imagery frequently drew on heroic realism.[64] Nazi youth and the SS were depicted monumentally, with lighting posed to produce grandeur.[64] Graphic design also played a part in Nazi Germany through the use of the swastika.[65] The swastika was in existence long before Hitler came into power—serving purposes that were much more benign than the ones it [the swastika] is associated with today.[66] Because of the stark, graphic lines used to create a swastika, it was a symbol that was very easy to remember.[65] LiteratureThe Reich Chamber of Literature Reichsschriftstumskammer[67] Literature was under the jurisdiction of Goebbels's Ministry of Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment. According to Grunberger, "At the beginning of the war this department supervised no less than 2,500 publishing houses, 23,000 bookshops, 3,000 authors, 50 national literary prizes, 20,000 new books issued annually, and a total of 1 million titles constituting the available book market."[68] Germany was Europe's biggest producer of books—in terms both of total annual production and the number of individual new titles appearing each year.[69] In 1937, at 650 million RM, the average sales value of the books produced took third place in the statistics on goods, after coal and wheat.[70] The first Nazi literature commission set itself the goal of eradicating the literature of the 'System Period', as Weimar was contemptuously called, and of propagating volkisch-nationalist literature in the Nazis state.[71] Literature was recognized early on as an essential political tool in Nazi Germany, as virtually 100 percent of the German population was literate.[72] "The most widely-read-or displayed-book of the period was Hitler's Mein Kampf, a collection (according to Lion Feuchtwanger) of 164,000 offences against German grammar and syntax; by 1940, it was, with 6 million copies sold, the solitary front-runner in the German best-seller list, some 5 million copies ahead of Rainer Maria Rilke and others."[68] Richard Grunberger says, "In 1936 literary criticism as hitherto understood was abolished; henceforth reviews followed a pattern: a synopsis of content studded with quotations, marginal comments on style, a calculation of the degree of concurrence with Nazi doctrine and a conclusion indicating approval or otherwise."[73] The Nazis permitted much foreign literature to be read, in part because they believed that the writings of authors such as John Steinbeck and Erskine Caldwell substantiated the Nazis' condemnation of Western society as corrupt.[74] However, when the United States entered the war, all foreign authors were strictly censored. Themes in Nazi literature were defined as a range of "permissible literary expression" largely limited to four subjects: German war glorification, Nazism and race, blood and soil, and the Nazi movement."[75] Popular Nazi Germany authors included Agnes Miegel, Rudolf Binding, Werner Bumelburg and Börries von Münchhausen.[76] Fronterlebnis (War as a Spiritual Experience)This was one of the most popular themes during the interwar period. Writers celebrated the "heroics of front-line soldiers in [World War I], ... the thrill of combat and the sacredness of death when it is in the service of the fatherland."[77] Popular writers in this genre included Ernst Jünger and Werner Beumelburg (de), an ex-officer.[77] Prominent books include Ernst Junger's Storm of Steel (1920), Struggle as Inner Experience (1922), Storms (1933), Fire and Blood (1925), The Adventurous Heart (1929), and Total Mobilization (1931). Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil)Novels in this theme often featured an instinctive and soil-bound peasant community that warded off alien outsiders who sought to destroy their way of life.[77] The most popular novel of this kind was Hermann Lons's Wehrwolf published in 1910. Historical ethnicityKlaus Fischer says Nazi literature emphasized "Historic Ethnicity—that is, how a group of people defines itself in a process of historical growth. Writers tried to highlight prominent episodes in the history of the German people; they stressed the German mission for Europe, analyzed the immutable racial essence of Nordic man, and warned against subversive or un-German forces—the Jews, Communists, or Western liberals."[77] Prominent writers included: Erwin Guido Kolbenheyer (Die Bauhutte: Elemente einer Metaphysik der Gerenwart; The building hut: Elements of a contemporary metaphysics, 1925), Alfred Rosenberg (Der Mythus des 20.Jahrhunderts; The myth of the twentieth century, 1930), Josef Weinheber, Hans Grimm (Volk ohne Raum; People without living space, 1926), and Joseph Goebbels (Michael, 1929). ArchitectureHitler favored hugeness, especially in architecture, as a means of impressing the masses.[78] "A once mediocre artist and aspiring architect, Hitler also pronounced upon the ‘decadence’ of modern art and pushed his planners to create monumental buildings in older neoclassical or art deco styles."[79]  Theatre and cinema"The Reich Film Chamber (Reichsfilmkammer) controlled the lively German film industry, while a Film Credit Bank (also under Goebbels' control) centralized the financial aspects of film production."[80] Approximately 1,363 feature pictures were made during Nazi rule (208 of these were banned after World War II for containing Nazi Propaganda).[81] Every film made in Nazi Germany (including features, shorts, newsreels, and documentaries) had to be passed by Joseph Goebbels himself before they could be shown in public.[82] Mass culture was less stringently regulated than high culture, possibly because the authorities feared the consequences of too heavy-handed interference in popular entertainment.[83] Thus, until the outbreak of the war, most Hollywood films could be screened, including It Happened One Night, San Francisco, and Gone with the Wind. While performance of atonal music was banned, the prohibition of jazz was less strictly enforced. Benny Goodman and Django Reinhardt were popular, and leading English and American jazz bands continued to perform in major cities until the war; thereafter, dance bands officially played "swing" rather than the banned jazz.[84] A film premiered in Berlin on November 28, 1940, which was clearly a tool used to promote Nazi Ideology. The release of the film Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) was only two months prior to the announcement made by German officials of the establishment of the ghetto in Łódź. The film was portrayed in the Nazi press as a documentary to emphasize the cinema as truth, when in reality it was nothing more than propaganda to raise hatred against the Jewish community in its viewers.[85] The filmmaker, Fritz Hippler, used numerous visual techniques to portray Jews as a filthy, degenerate, and disease-infested population. Purporting to provide the viewer with an in-depth look at the Jewish lifestyle, the film showed staged scenes of Łódź (soon to be ghetto) with the presence of flies and rats, to suggest a dangerous-to-life area of Europe, which, in turn, only perpetuated underlying superstition and fear to the viewer. To add to this staged and exaggerated scene of filth was a warning released by officials of The Reich: an advisory that Łódź is an area of widespread infectious disease. The film director utilized racist cinema to bolster the illusion that Jews were parasites and corruptors of German culture.[86] Hippler made use of voice-overs to cite hate speeches or fictitious statistics of the Jewish population. He also borrowed numerous scenes from other films, and presented them out of context from the original: for example, a scene of a Jewish businessman in the United States hiding money was accompanied with a bogus claim that Jewish men get taxed more than non-Jews in the United States, which was used to insinuate that Jews withhold money from the government. Through the repetitive use of side angles of Jewish people, who were filmed (without knowledge) while looking over their shoulder at the camera, Der ewige Jude created a visual suggesting a shifty and conspiring nature of Jews. Yet another propaganda technique was superposition. Hippler superimposed the Star of David onto the tops of world capitals, insinuating an illusion of Jewish world domination.[87] Der ewige Jude is notorious for its anti-Semitism and its use of cinema in the fabrication of propaganda, to satisfy Hitler and to embrace the Germanic ideology that would fuel a nation in support of an obsessive leader.[88] "On the lighter side, a Jewish actor named Leo Reuss fled Germany to Vienna, where he dyed his hair and beard and became a specialist in 'Aryan' roles, which were greatly praised by the Nazis. Having had his fun, Reuss revealed he was a Jew, signed a contract with MGM, and departed for the United States".[89]  FührermuseumApart from auctioning art that was to be purged from Germany's collection, Germany's art that was considered as especially favourable by Hitler were to be combined to create a massive art museum in Hitler's hometown of Linz, Austria for his own personal collection. The museum to-be by 1945 had thousands of pieces of furniture, paintings, sculptures and several other forms of fine craft. The museum was to be known as the "Führermuseum". By the late spring of 1940 art collectors and museum curators were in a race against time to move thousands of pieces of collectables into hiding, or out of soon-to-be-occupied territory where it would be vulnerable to confiscation by German officials—either for themselves or for Hitler. On June 5, a particularly important movement of thousands of paintings occurred, which included the Mona Lisa, and all were hidden in the Loc-Dieu Abbey located near Martiel during the chaos of invasion by German forces. Art dealers did their best to hide artwork in the best places possible; Paul Rosenberg managed to move over 150 great pieces to a Libourne bank, which included works by Monet, Matisse, Picasso, and van Gogh. Other collectors did whatever they could to remove France's artistic treasures to the safest locations feasible at the time; filling cars, or large crates en route to Vichy, or south through France and into Spain to reach transport by boat. Art dealer Martin Fabiani, whom after WWII was arrested for his involvement in Nazi art looting,[90] moved mass quantities of pictures: drawings and paintings from Lisbon destined for New York, however they were seized by the Royal Navy which relocated them to Canada, in the charge of the Registrar of the Exchequer Court of Canada where they were to remain until the end of the war. Similar shipments landed in New York.[91][92] By the end of June, Hitler controlled most of the European continent. As people were detained, their possessions were confiscated; if they were lucky enough to escape, their belongings left behind or in storage became the property of Germany. By the end of August, officials of the Reich were granted permission to access any shipping containers and remove any desirable items inside. As well as looting goods that were to be shipped out of occupied territories, Arthur Seyss-Inquart authorized the removal of any objects found in houses during the invasion, after which a long and thorough search was in effect for European treasures.[93]  Artwork became an important commodity in the German economy: no one in German or axis-controlled countries was allowed to invest outside of the new Germanic-controlled territory, which in turn created a self-contained market. With few options available for investments, art was of great importance to anyone with cash, including the Führer himself, as a safe form of investment, and even in trade for the lives of others. At the height of trading in 1943, art was used by Pieter de Boers, the head of the Dutch association of art dealers and the largest art seller to Germans in the Netherlands, in the exchange of the release of his Jewish employee. Demand began to increase dramatically, forcing prices to rise, and only furthering the desire to discover hidden treasures within occupied territory.[94] As exploration continued within occupied France, and by Hitler's orders, a list was created which included all of the great works of art in France, and the German Currency Unit began to open private bank units which contained countless collectors' property and possible items on the list. The owner of the vault was required to be present. One particular investigation of a vault was that of Pablo Picasso; he chose a rather clever tactic when soldiers searched the contents of his vault. He packed his own artworks with countless other artists’ works of his collection in a chaotic manner, with the result that the investigators thought that nothing in the collection was significant, and took nothing.[95] As confiscations began to pile up in massive quantities, the items filled the Louvre, and forced Reich officials to use the Jeu de Paume, a small museum, for additional space, and for proper viewing of the collection. The grand stockpile of art was ready for Hitler to choose from: Hitler had first choice for his own collection; second were objects that would complete collections of the Reichsmarschall; third was intended for whatever was useful to support Nazi ideology; a fourth category was created for German museums. Everything was supposed to be appraised and paid for, with proceeds being directed to French war-orphans.[96] Hitler also ordered the confiscation of French works of art owned by the state and the cities. Reich officials decided what was to stay in France, and what was to be sent to Linz. Further orders from Hitler also included the return of artworks that were looted by Napoleon from Germany in the past. Napoleon is considered the unquestioned record holder in the act of confiscating art.[97]  Individual NSDAP artistsAccording to Klaus Fischer, "Many German writers, artists, musicians, and scientists not only stayed but flourished under the Nazis, including some famous names such as Werner Heisenberg, Otto Hahn, Max Planck, Gerhart Hauptmann, Gottfried Benn, Martin Heidegger, and many others".[98] In September 1944, the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda prepared a list of 1,041 artists considered crucial to Nazi culture, and therefore exempt from war service. This Gottbegnadeten list provides a well-documented index to the painters, sculptors, architects and filmmakers who were regarded by the Nazis as politically sympathetic, culturally valuable, and still residing in Germany at this late stage of the war. Official painters

Official sculptors

Writers

Actors and actresses

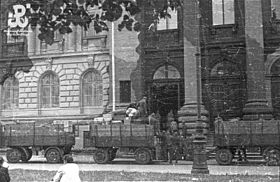

Degenerate art forms Hitler's rise to power on January 31, 1933, was quickly followed by actions intended to cleanse the culture of degeneracy: book burnings were organized, artists and musicians were dismissed from teaching positions, artists were forbidden to utilize any colors not apparent in nature, to the "normal eye",[104] and curators who had shown a partiality to modern art were replaced by Nazi Party members.[105] "Through the Ministry of Propaganda or the ERR, the Nazis destroyed or quarantined the culture of all the nations they invaded."[106] "A four-man purge tribunal (Professor Ziegler, Schweitzer-Mjolnir, Count Baudissin and Wolf Willrich) toured galleries and museums all over the Reich and ordered the removal of paintings, drawings and sculptures that were regarded as 'degenerate'."[107] "The swathe these four apocalyptic Norsemen cut through Germany's stored-up artistic treasure has been estimated at upwards of 16,000 paintings, drawings, etchings and sculptures: 1,000 pieces by Nolde, 700 by Haeckel, 600 each by Schmidt-Rottluff and Kirchner, 500 by Beckmann, 400 by Kokoschka, 300–400 each by Hofer, Pechstein, Barlach, Feininger and Otto Muller, 200-300 each by Dix, Grosz and Corinth, 100 by Lehmbruck, as well as much smaller numbers of Cézannes, Picassos, Matisses, Gauguins, Van Goghs, Braques, Pissarros, Dufys, Chiricos and Max Ernst."[108][failed verification] On March 20, 1939, more than 4000 of those works seized were burned in the courtyard of the headquarters of the Berlin Fire Department.[109] The term Entartung (or "degeneracy") had gained popularity in Germany by the late 19th century when the critic and author Max Nordau devised the theory presented in his 1892 book, Entartung.[110] Nordau drew upon the writings of the criminologist Cesare Lombroso, whose The Criminal Man, published in 1876, attempted to prove that there were "born criminals" whose atavistic personality traits could be detected by scientifically measuring abnormal physical characteristics. Nordau developed from this premise a critique of modern art, explained as the work of those so corrupted and enfeebled by modern life that they have lost the self-control needed to produce coherent works. Explaining the painterliness of Impressionism as the sign of a diseased visual cortex, he decried modern degeneracy while praising traditional German culture. Despite the fact that Nordau was Jewish (as was Lombroso), his theory of artistic degeneracy would be seized upon by the Nazis during the Weimar Republic as a rallying point for their anti-Semitic and racist demand for Aryan purity in art. Germany lost "thousands of intellectuals, artists, and academics, including many luminaries of Weimar culture and science", according to Raffael Scheck.[111] Fischer says that "as soon as Hitler seized power, many intellectuals rushed to the exits."[112] Though pornography was officially banned in Nazi Germany, it has been acknowledged that pornographic films were privately filmed and screened for senior Nazi Party figures, and were also traded to north Africa for insect repellent and other commodities.[113] One notable series of erotic films which were secretly shot in 1941 were Sachsenwald films.[113] Proscribed literatureAccording to Pauley, "literature was the first branch of the arts to be affected by the Nazis."[114] "As early as April 1933, the Nazis had compiled a long blacklist of left, democratic, and Jewish authors which included several famous authors of the nineteenth century."[114] Large scale book burnings were staged across Germany in May 1933. Two thousand five hundred writers, including Nobel prize winners and writers of worldwide best sellers, left the country voluntarily or under duress, and were replaced by people without international reputations."[114] In June 1933, the Reichsstelle zur Forderung des deutschen Schrifttums (Reich Office for the Promotion of German Literature) was established.[71] Jan-Pieter Barbian says, "On the level of the state, the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda and the Reich Chamber of Literature had to share responsibility for literary policy with the new Reich Ministry of Science, Education, and Public Instruction and the Foreign Office."[115] "The full repertoire—which also included the consistent removal of Jews and political opponents—was brought to bear during the twelve years of Nazi rule: on writers and publishers; book wholesaling; the retail, door-to-door, and mail-order book libraries, public libraries, and research libraries."[115] Between November 1933 and January 1934, publishers were informed "that supplying and distributing the works named is undesirable for national and cultural reasons and must therefore cease."[116] Publishers, who often faced enormous economic losses when books were banned, received letters stating that the "authorities responsible would proceed against any indiscretion in the most rigorous manner".[117] Companies which had published primarily "the fiction of naturalism, expressionism, Dadaism, and New Objectivity; modern translated literature; and critical nonfiction ... suffered enormous economic losses."[117] A few of the hardest hit publishers were Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, S.Fischer Verlag, Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlags-AG, Rowohlt, Ullstein Verlags-AG, and Kurt Wolff Verlags.[117] In 1935, the same year that "Goebbels assumed complete control over censorship," the Reichsschrifttumskammer banned the work of 524 authors.[106] "The Office for the Supervision of Ideological Training and Education of the NSDAP...became another watchdog of the state, spying on writers, developing black lists, encouraging book burnings, and emptying museums of 'non-German' works of art."[118] Punishments varied, some individuals were censored or had their work destroyed or publicly ridiculed, while others were incarcerated in concentration camps.[119] "During World War II, 1939–1945, identical indexes of forbidden literature were applied by the Nazis in all occupied countries as well as in Germany's allied countries: Denmark, Norway, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Poland, Yugoslavia, Greece, and of course, Germany."[120] Book burnings Described as a cleaning action or Sauberung,[119] book burnings, known as the Bücherverbrennung in Germany, and sometimes referred to as the "bibliocaust", began on May 10, 1933, when the Association of German Students confiscated some 25,000 books from the Institute for Sexual Research and several captured Jewish libraries, which were burned in Opernplatz.[121] Like a lit fuse, the bonfire triggered book burning in other cities all over Germany, including Frankfurt and Munich, where the burnings were part of an orchestrated program, including music and speeches.[121] "Political police groups like the SA, the SS, and the Gestapo unleashed a campaign of intimidation that often frightened people into burning their own books."[122] "The blind writer Helen Keller published an Open Letter to German Students: 'You may burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe, but the ideas those books contain have passed through millions of channels and will go on.'"[123] Degenerate Art exhibitionModern artworks were purged from German museums. Over 5,000 works were initially seized, including 1,052 by Nolde, 759 by Heckel, 639 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and 508 by Max Beckmann, as well as smaller numbers of works by such artists as Alexander Archipenko, Marc Chagall, James Ensor, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh.[124] These became the material for a defamatory exhibit, Entartete Kunst ("Degenerate Art"), featuring over 650 paintings, sculptures, prints, and books from the collections of thirty-two German museums, that premiered in Munich on July 19, 1937, and remained on view until November 30 before travelling to eleven other cities in Germany and Austria. In this exhibition, the artworks were deliberately presented in a disorderly manner, and accompanied by mocking labels. "To 'protect' them, children were not allowed in."[125]

Coinciding with the Entartete Kunst exhibition, the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) made its premiere amid much pageantry. This exhibition, held at the palatial Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), displayed the work of officially approved artists such as Arno Breker and Adolf Wissel. At the end of four months Entartete Kunst had attracted over two million visitors, nearly three and a half times the number that visited the nearby Grosse deutsche Kunstausstellung.[9] The Degenerate Art Exhibition included works by some of the great international names—Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky—along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, and Georg Grosz. The exhibition handbook explained that the aim of the show was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them". Works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist", says Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and author of several books on art and politics of the Nazi era. Hitler had been an artist before he was a politician—but the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes that he preferred had been dismissed by the art establishment in favor of abstract and modern styles. So the Degenerate Art Exhibition was his moment to get his revenge. He had made a speech about it that summer, saying "works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people". The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the 112 artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish. The art was divided into different rooms by category—art that was blasphemous, art by Jewish or communist artists, art that criticized German soldiers, art that offended the honor of German women. One room featured entirely abstract paintings, and was labelled "the insanity room". The idea of the exhibition was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people. The curators went to some lengths to get the message across, hiring actors to mingle with the crowds and criticize the exhibits. The Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich attracted more than a million visitors—three times more than the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibition.[127] Individual artists forbidden under Nazi ruleBanned in German-occupied Europe and/or living in exile: See also

Notes

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Art approved by the Nazi regime.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||