|

Birmingham Americans

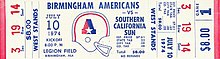

The Birmingham Americans were a professional American football team located in Birmingham, Alabama. They were members of the four-team Central Division of the World Football League (WFL). The Americans, founded in late December 1973, played in the upstart league's inaugural season in 1974. The team was owned by William "Bill" Putnam, doing business as Alabama Football, Inc. The club played all of their home games at Legion Field. The most successful of the World Football League franchises, the Americans led the league in attendance and won all 13 of their home games. They developed a reputation for come-from-behind victories and winning by narrow margins. The Americans finished the 1974 regular season at 15–5 and won the 1974 World Bowl by one point over the Florida Blazers. Financially unstable due to investor reluctance and lavish signing bonuses paid to lure National Football League (NFL) players to the new league, the team folded after only one season. Most of the team's assets were seized to pay back taxes; failed lawsuits to recover the signing bonus money kept the team in the headlines long after the WFL was itself defunct. The Americans were replaced as the Birmingham WFL franchise for the 1975 season by a new team called the Birmingham Vulcans. Franchise historyAtlanta businessman William R. "Bill" Putnam was awarded an expansion franchise for Birmingham in the upstart World Football League and secured a lease to play at Legion Field.[1][2] The five original investors in Alabama Football, Inc., all Atlanta businessmen, were majority owner Bill Putnam, Cecil Day, Lon Day, Jay Donnelly, and Erv Plesko.[3] Between them they had already invested over US$1.5 million in the franchise and hoped to find ten investors in Birmingham to buy in for an additional $150,000 each.[3] Unable to find local investors for the team, Putnam threatened to move the Americans from Birmingham before the start of the 1974 season.[4] However, with more than 10,000 season tickets sold before the first game, the team's position in Birmingham was secured for the year.[5] Vince Costello, an assistant coach with the Cincinnati Bengals, was chosen as head coach/general manager. A few days after the announcement, he turned down the job to become an assistant with the Miami Dolphins. Jack Gotta, head coach of the Ottawa Rough Riders of the Canadian Football League (CFL), was hired.[6] Gotta put together a solid squad, including veteran quarterback George Mira, rookie passer Matthew Reed, wide receiver Dennis Homan, running back Charley Harraway of the Redskins, and former St. Louis Cardinals and Auburn standout safety Larry Willingham.[5][7] Johnny Musso, a former Alabama fullback with the CFL's BC Lions, was the Americans' first round pick in the WFL's "pro draft" in March 1974.[8][9] Birmingham selected 42-year-old retired professional basketball player and former Atlanta Hawks head coach Richie Guerin in the fortieth and last round of that draft,[9] drawing laughter from the audience.[10] Radio play-by-play duties were handled by Larry Matson with color commentary provided by a series of guest commentators.[11] 1974 season  Birmingham competed in the Central Division, along with the Chicago Fire, Memphis Southmen, and Detroit Wheels.[13] The team began training camp on June 3 at the Marion Military Institute in Marion, Alabama, and broke camp during the first week in July.[14] The Americans played a 20-game regular season with no pre-season games. (The team did however play one "controlled scrimmage" against the Jacksonville Sharks on Saturday, June 29, 1974.)[15] Most games were played on Wednesday nights with nationally televised games on Thursday nights.[16][17] The Americans won their first ten games, finishing the regular season 15–5, in second place in the Central Division behind Memphis.[18] Midway through the season, the World Football League Players Association was formed and Americans fullback Charley Harraway was selected to serve as its first president.[19] Alfred Jenkins was named the team's Most Valuable Player for the 1974 season.[20] First halfThe Americans' first game was played on July 10, 1974, against the Southern California Sun in front of a crowd of 53,231 at Legion Field.[21] (The announced attendance of 53,231 was inflated. The actual attendance figure was 43,031 for the opening game, of which 41,799 had paid.)[22][23] Held scoreless by the Sun for the first three quarters and trailing by a touchdown at the start of the fourth quarter, the Americans came back to win 11–7.[24] In their first road game, the Americans overcame a 26-point deficit at halftime to win 32–29 over the New York Stars in front of 17,943 at Downing Stadium on July 17, 1974.[25] The second home game, a 58–33 win over the Memphis Southmen on July 24, drew an announced attendance of 61,319 fans (actual attendance was 54,413 with 40,367 paying).[22][23][26][27] In the first of back-to-back games against the Detroit Wheels, Birmingham quarterback Matthew Reed scored the game-winning touchdown with 2:12 remaining in the fourth quarter to secure a 21–18 victory. The July 31, 1974, road win was witnessed by 14,614 fans in Rynearson Stadium in Ypsilanti, Michigan.[28] Reed led a four-play touchdown drive in the last 26 seconds of the Americans' third home game to give Birmingham another win, 28–22 over Detroit.[29] An announced 56,453 (33,993 paying) fans sat through rain and foul weather to see the victory on August 7.[23][26] Weather was also a factor in the Americans' fourth home game as driving rain delayed the start of the August 14 game against The Hawaiians and reduced attendance to 43,297.[30] Fans at Legion Field saw a halftime show featuring grass skirt-clad hula dancers with music provided by the Tuscaloosa High School marching band in addition to the 39–0 victory by Birmingham.[30][31] The Americans travelled to Florida to face the Jacksonville Sharks, 27,140 Jacksonville fans, and the Sharks' new coach, Charlie Tate.[32] Birmingham managed a 15–14 win with a touchdown by Charley Harraway and action point by quarterback Matthew Reed with 19 seconds remaining in the August 21 game.[32] The Americans then went north to face the Chicago Fire on Thursday, August 29, 1974, in their first nationally televised game.[33] Birmingham won that match-up 22–8 with 44,732 fans in attendance at Soldier Field.[33] A quick turnaround found the Americans back home for a Labor Day game against the Eastern Division-leading Florida Blazers on Monday, September 2, 1974, with 36,529 fans in the stadium.[34][35] A fourth quarter scoring drive kept Birmingham's winning streak intact with a narrow 8–7 win over Florida.[36] Another short week found the Americans in action on Saturday, September 7, 1974, at home against the Chicago Fire.[37] Weather was again a factor as Hurricane Carmen pushed "torrential rains" into the Birmingham area, drenching the field, the players, and the 54,872 fans in attendance.[38][39] A 34-yard field goal by Earl Sark with less than one minute to go in the game was the difference in Birmingham's 41–40 victory over Chicago.[37] Second halfFour games in just two weeks proved too much for the Americans as their ten-game winning streak came to an end on September 11 with a loss to the Memphis Southmen.[40] After rallying for seven fourth-quarter comebacks in their first ten games, Birmingham lost 46–7 in front of a 30,675-strong crowd at Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium.[41] The Americans' nationally televised September 19 home game against the Houston Texans proved to be the last WFL game for Houston as the following week the Texans were taken over by the league and relocated to Shreveport, Louisiana.[40][42] Just 33,619 fans at Legion Field saw the 42–14 win for Birmingham, the beginning of a slow, downward trend in attendance figures that coincided with the start of college football season.[43] The Americans who, in the words of UPI sportswriter Joe Carnicelli, "made the last-minute score almost their trademark", were upset 26–21 by the Portland Storm with 14,273 in the stands at Portland's Civic Stadium.[44] The Storm scored the game-winning touchdown with 35 seconds left in the September 25 road contest.[45] The long flight across the Pacific Ocean did not help Birmingham for their October 2 game in Honolulu. The Americans lost 14–8 to The Hawaiians in front of 12,039 fans at Honolulu Stadium (demolished in 1976).[13] Birmingham trailed after the first quarter but rallied to defeat the Portland Storm 30–8 in front of a below-average 25,621 hometown fans at Legion Field on October 9.[46] The following week, on October 16, the Americans lost their third game in four weeks, falling 29–25 to the Southern California Sun before a crowd of 25,247 in Anaheim.[47]  In mid-October, Americans team president Carol Stallworth announced that the team's remaining home games would start at 7 p.m. to "make it easier for our early-rising fans" than the original 8 p.m. kickoffs.[48] Also, the Americans' game schedule was adjusted to accommodate the league's shifting and struggling franchises. The October 23 game against the Shreveport Steamer scheduled for Birmingham would be played on the road in Shreveport instead and, in return, their November 13 match-up was relocated from Shreveport's State Fair Stadium to Birmingham's Legion Field.[48] On the road unexpectedly, the Americans suffered their only shutout of the season, falling to the Steamer 31–0 in front of 24,617 fans.[49][50] The October 30 game with the Florida Blazers was moved from Orlando to Birmingham, giving the Americans 11 home games in their 20-game regular season.[48] This was one of two home games relocated out of Orlando as part of a legal settlement between the WFL and Blazers ownership to sell the financially troubled team, pay off debts, and get checks to players who had not been paid since mid-September.[51][52] Not included in the Americans' season ticket package, this extra home game tallied the lowest home attendance to date for the Americans with 21,872 present at Legion Field.[53] In that game, quarterback George Mira injured his shoulder in the second quarter and rookie Matthew Reed came off the bench to lead the Americans to a 26–18 victory.[54] Birmingham scored all of their points in the first half of their November 6 home game against the Philadelphia Bell then fought off a second-half comeback attempt by Philadelphia to win 26–23 before 22,963 at Legion Field.[55][56] With this victory, the team clinched a spot in the WFL playoffs but the Birmingham franchise's increasing financial woes put the playing of the final regular season game in doubt.[56] A deal with tax officials was worked out and the Americans wrapped up the regular season on November 13 with a 40–7 win over the Shreveport Steamer, marking three consecutive home game victories.[57] With doubts as to whether this game would be played persisting until the day of the contest, ticket sales were poor; only 14,794 fans saw the final regular season game the Americans would play.[57] Although they slumped to a .500 record in the second half, it was enough to finish second, behind Central Division-winning Memphis, at 15–5 and take the wild card slot in the six-team playoff series and earn a bye in the first round.[58] Post-seasonAfter receiving a bye from the quarterfinal playoff games, Birmingham beat the Western Division-winning The Hawaiians in the semifinals, 22–19, in front of a sparse 15,379 at Legion Field. The Americans advanced to host the World Bowl, the WFL's championship game, on Thursday, December 5.[59] Unpaid since early October, the Americans players staged a walkout on the Monday before the title game demanding back pay.[60][61] The players returned when team ownership promised to buy each player a championship ring.[2] The game went forward and Birmingham beat the Florida Blazers by a point, 22–21.[6][62] This game was played with 32,376 fans in the stands, over 20,000 fewer than had witnessed the Americans' first game just five months before.[6][21] This was the only championship game ever held by the WFL, as it folded 12 games into the 1975 regular season.[2][63] Schedule and results

Regular season

Playoffs

Financial falloutIn early November 1974, Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley filed suit in Jefferson County Circuit Court for a tax lien against the team's property. The suit sought to recover the $30,000 in state income withholding taxes and more than $57,000 in sales taxes for August and September 1974 (plus a then-undetermined amount due for October 1974) due to the state of Alabama. The judge ordered Jefferson County's sheriff to "attach the property, real, personal and mixed, of the defendant, wherever it may be in Jefferson County."[71] The team also admitted it owed roughly US$14,000 in back sales taxes to both Jefferson County and to the city of Birmingham.[72] The Birmingham motel where the coaching staff had its offices evicted the team for non-payment on November 14.[72] At that time, the Americans had not paid their players for five weeks, nor their staff and coaches for two weeks.[72] On November 18, 1974, the Internal Revenue Service filed its own tax liens of about $237,000 against the Americans and $160,000 against team owner Bill Putnam.[73] Putnam announced at a press conference that he was trying to raise the funds to pay the team's debts. He reported that the team had taken in about $2.3 million in gate receipts to that point, which left him "only $300,000 short of operating the club", but revealed that the team had also "paid out over $1.2 million in bonuses to future players." He asserted that the team would not be in such dire financial straits if that bonus money had not been paid.[73] Putnam said that he would need to raise $750,000 by November 28 so the team could pay back taxes due to the state, county, and city as well as the salaries of players who had not been paid in four weeks. He said "If the money comes from Birmingham, we'll stay here but if the money comes from people in Timbuktu who want the team in Timbuktu, them we'll move there." Putnam said a group from New York was interested in purchasing the Americans.[4] Putnam speculated that one reason he had been unable to secure "local money" to invest in the franchise was that local interests were still hoping to bring an NFL franchise to the city.[73] Loss of propertyTo attempt to pay back the debt and to allow the World Bowl to be played, the teams negotiated a deal with creditors to accept a portion of the gate receipts. After paying fixed costs associated with the game, the IRS and others due money would split 30 percent of the revenue with the teams receiving the remaining 70 percent to pay long-overdue player salaries.[6] This revenue was split by the Americans and Blazers on a 60/40 basis with the World Bowl winners receiving the larger share.[6] Based on gate receipts, each Americans player was to be paid about US$1,400 for their World Bowl play with each Blazers player taking home about US$1,000.[74] Hibbett Sporting Goods had provided uniforms and football equipment to the Americans but still had not been paid US$38,800 by the end of the season.[75] Immediately after the championship victory, members of the Jefferson County Sheriff's Department seized the team's equipment and uniforms from the locker room.[76] One week later, Hibbett Sporting Goods began selling the reclaimed gear as souvenirs and Christmas presents in their retail stores.[77] Loss of playersOakland Raiders quarterback Kenny Stabler signed a contract with Birmingham in 1974. In January 1975, a circuit court judge found that the team was in arrears on payment of the remaining US$30,000 due to Stabler of the US$100,000 he was guaranteed for 1974 and so ruled that the Americans were in breach of contract and thus Stabler was released.[78] The three-year deal was to have paid Stabler US$100,000 in both 1974 and 1975 while he played out his contract option with the Raiders and US$135,000 for the 1976 season when he would have been playing for the Americans.[79] The judge ruled Stabler released from his contract and voided any debt to him by the then-struggling Americans franchise.[79] While the successor to the Americans, the Vulcans were a different organization and ownership from the Americans and did not assume any of their debts or obligations, including any of the Americans' player contracts.[80] The Internal Revenue Service seized the Americans player contracts and placed them up for auction in March 1975 to pay the team's US$236,691 in overdue taxes but a judge ruled all of these player contracts breached and of no value.[80][81] In any case, the auction was cancelled when a judge ruled that Birmingham Trust National Bank had a valid prior claim to the contracts.[82] Loss of franchiseNewly elected WFL president Chris Hemmeter was determined to impose a measure of financial sanity on the league. Among other things, he insisted that all potential owners establish a $650,000 line of credit with the league. Putnam tried to find more local investors to meet this requirement, but there were few takers.[83] In late January 1975, Hemmeter revoked the Americans' franchise due to the team's chronic financial woes. Hemmeter stated that the Americans owed a total of $2 million in bills, taxes and missed player salaries. However, the league said it had every intention of placing a new team in Birmingham.[84] Putnam responded by suing the league, demanding to be compensated with the rights to New York City. However, the suit went nowhere.[83] On March 7, 1975, Ferd Weil, as president of the board of directors of a new WFL franchise for Birmingham, announced that the Birmingham WFL team for 1975 would be called the Birmingham Vulcans, a name previously registered by a group of Birmingham businessmen who had been trying to secure an NFL franchise for Birmingham.[85] The Vulcans began selling shares of stock to the general public. Priced at US$10 per share and sold only in blocks of 10 shares, the team hoped to raise $1.5 million with this offering.[86] The Vulcans officially secured the Birmingham franchise in April 1975. When the WFL folded for good 12 games into the ill-fated 1975 season, the Vulcans had the best record.[87] Legal pursuitsKenny Stabler was not the only NFL player that the Americans signed to contracts but who never played for the WFL team. Detroit Lions wide receiver Ron Jessie was paid a $45,000 signing bonus in early 1974, to begin playing for the Americans in the 1975 season after completing his option year with the Lions.[88] Dallas Cowboys defensive tackle Jethro Pugh and offensive tackle Rayfield Wright each received a $75,000 signing bonus, with Pugh set to start playing for the Americans in 1976 and Wright in 1977.[89][90] Pittsburgh Steelers defensive end L. C. Greenwood received a $50,000 signing bonus to play from 1975.[91][92][93] However, when the team folded both the WFL commissioner and a federal judge ruled that the player contracts had all been voided.[80] These players remained in the NFL, playing neither for the Americans nor the successor Birmingham Vulcans team. Bill Putnam and his Alabama Football, Inc., still the legal owners of what little remained of the Americans' assets, made headlines through the late 1970s when he sued these NFL players claiming "breach of contract" to recover the signing bonus money.[94] The players were ultimately able to keep the money after the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in their favor.[94][95] LegacyFinancially devastated, former Americans team president Carol Stallworth became a bartender in a downtown Birmingham sports bar in early 1975.[1][96] Most of the former Americans players signed on with the Birmingham Vulcans for the 1975 WFL season.[97] Notable exceptions included star players Charley Harraway, Alfred Jenkins, Paul Robinson, and veteran quarterback George Mira.[97] The Birmingham Bulls of the World Hockey Association held "Jack Gotta Night" on December 26, 1976, in honor of the former Americans head coach.[98] By July 1976, Americans owner Bill Putnam was working to buy a World Hockey Association franchise and relocate it to Hollywood, Florida, as the "Florida Breakers".[99] The team was planned to start play in October 1976 with the Hollywood Sportatorium as its home ice.[99] In August 1976, Putnam announced that his plan had "collapsed" but he would continue his attempts to bring a hockey franchise to south Florida.[100] Fans of the team organized a reunion celebration held July 9–10, 2004, in honor of the 30th anniversary of the Americans' first game played on July 10, 1974, against the Southern California Sun. One reason for the festivities was to help pay for the promised World Bowl championship rings that many players did not receive from the financial failing franchise.[2] Dayton Daily News sportswriter Chick Ludwig discovered the omission while doing research for a book. He used his investigative skills to find that Jonsil Manufacturing in El Paso, Texas, made the original rings and could create replacement rings for $809 each.[63][101] The story received national attention which prompted Nestlé and the AF2 Birmingham Steeldogs to help sponsor the reunion at the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in Birmingham.[63][101] As of April 2010[update], three former Birmingham Americans players have been inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. Muscle Shoals native Dennis Homan, who also played in Super Bowl V for the Dallas Cowboys, was inducted in the Class of 1999.[102] Oxford native Terry Henley, who also played pro football for the Atlanta Falcons, Washington Redskins, and New England Patriots, was inducted in the Class of 2000.[103] Cullman native Larry Willingham, who played for the St. Louis Cardinals and retired for medical reasons in 1973 but made a comeback in 1974 with the Americans, was inducted in the Class of 2003.[104][105] Willingham and Henley were also elected to the Auburn Tigers football "1970s Team of the Decade".[103][104] See alsoReferences

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||