|

Boulder, Colorado

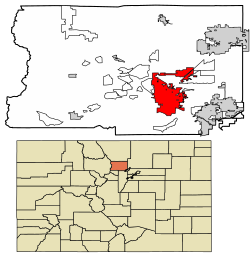

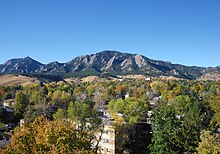

Boulder is a home rule city in and the county seat of Boulder County, Colorado, United States.[1] With a population of 108,250 at the 2020 census, it is the most populous city in the county and the 12th-most populous city in Colorado.[6] Boulder is the principal city of the Boulder metropolitan statistical area, which had 330,758 residents in 2020, and is part of the Front Range Urban Corridor. Boulder is located at the base of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, at an elevation of 5,430 feet (1,655 m) above sea level.[9][10] The city is 25 miles (40 km) northwest of the Colorado state capital of Denver. Boulder is a college town, hosting the University of Colorado Boulder, the flagship and largest campus of the University of Colorado system as well as numerous research institutes. HistoryArchaeological evidence shows that Boulder Valley has been continuously inhabited by Native American tribes for over 13,000 years, beginning in the late Pleistocene era. Throughout the Paleo-Indian, Archaic, and Late Prehistoric periods, Indigenous peoples moved seasonally between the mountains and plains, taking shelter in winter along the Front Range trough where Boulder now lies. By the 1500s, the area was occupied by Ute tribes, joined by Arapaho tribes in the early 1800s.[11] The Indigenous Nations who have ties to the Boulder Valley include the Apache, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, Pawnee, Shoshone, Sioux, and Ute peoples. In the 1800s, Euro-American settlers colonized the area.[12] Boulder was founded in late 1858 when prospectors led by Thomas Aikins arrived at Boulder Canyon during the Colorado Gold Rush. Arapaho leader Niwot allowed them to stay for the winter, but the settlers abused this peaceful approach, and some later took part in the Sand Creek massacre of Arapaho.[13] In early 1859, gold was discovered along Boulder Creek, drawing more miners and merchants to the area. The Boulder City Town Company was formed in February 1859 to establish a settlement at the canyon mouth. The Boulder, Nebraska Territory, post office opened on April 22, 1859.[14] On August 24, 1859, voters of the Pike's Peak mining region approved the formation of the Provisional Government of the Territory of Jefferson,[15] and on November 28, 1859, the extralegal Jefferson Territory created Jackson County with Boulder City as its seat.[16] By 1860, Boulder City had 70 cabins, occupied mainly by Anglo families. Non-whites like Chinese miners and black residents were part of early Boulder, but were rarely pictured.[11] The free Territory of Colorado was organized on February 28, 1861,[17] and Boulder County was created on November 1, 1861, with Boulder City as its seat The Arapaho were forced to relocate by the Treaty of Fort Wise. With declining numbers, Niwot's band soon moved to the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation. By 1862, the creek had yielded $100,000 in gold, and Boulder's population exceeded 300. On November 7, 1861, the Colorado General Assembly passed legislation to locate the University of Colorado in Boulder.[18] The City of Boulder City was incorporated on November 4, 1871.[3] On September 20, 1875, the first cornerstone was laid for the first building (Old Main) on the CU campus. Colorado became a state on August 1, 1876,[19] and the university officially opened on September 5, 1877.[20] The City of Boulder City shortened its name to the City of Boulder. In 1907, Boulder adopted an anti-saloon ordinance.[21] In 1916, statewide prohibition started in Colorado, and ended with the repeal of national prohibition in 1933.[22] HousingMedian home prices rose 60% from 2010 to 2015 to $648,200.[23] In 2024, the City Council of Boulder repealed a long-standing law that prevented Boulder from increasing new residential units by more than 1% in a year.[24] In 1959, city voters approved the "Blue Line" city-charter amendment, which restricted city water service to altitudes below 5,750 feet (1,750 m), to protect the mountain backdrop from development. In 1967, city voters approved a dedicated sales tax to acquire open space to contain urban sprawl. In 1970, Boulder created a "comprehensive plan" to dictate future zoning, transportation, and urban planning decisions. Hoping to preserve residents' views of the mountains, in 1972, the city enacted an ordinance limiting the height of newly constructed buildings. In 1974, a Historic Preservation Code was passed. In 1976, a residential-growth management ordinance, the Danish Plan, was passed.[25][26] Geography The city of Boulder is located in the Boulder Valley, where the Rocky Mountains meet the Great Plains. The Flatirons, slabs of sedimentary stone tilted up on the foothills, are located west of the city and are a widely recognized symbol of Boulder.[27] Boulder Creek is the primary flow of water through Boulder. The creek was named before the city's founding for all of the large granite boulders that have cascaded into the creek over the eons.[citation needed] It is from Boulder Creek that the city is believed to have taken its name.[citation needed] Boulder Creek has significant water flow, derived primarily from snow melt and minor springs west of the city.[citation needed] The creek flows into St. Vrain Creek east of Longmont, which is a tributary of the South Platte River. At the 2020 United States Census, the city had a total area of 17,514 acres (70.877 km2), including 664 acres (2.689 km2) of water.[6] The 40th parallel, 40 degrees north latitude, runs through Boulder and can be easily recognized as Baseline Road today. Boulder lies in a wide basin beneath Flagstaff Mountain just a few miles east of the continental divide and about 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Denver. Arapahoe Glacier provides water for the city, along with Boulder Creek, which flows through the center of the city.[28] Denver International Airport is located 45 miles (72 km) southeast of Boulder.[29] EnvironmentIn 1899, government preservation of open space around Boulder began, with the Congress of the United States approving the allocation of 1,800 acres (7.3 km2) of mountain backdrop/watershed extending from South Boulder Creek to Sunshine Canyon. Wildlife protectionBoulder has created an Urban Wildlife Management Plan which sets policies for managing and protecting urban wildlife.[30] The city's Parks and Recreation and Open Space and Mountain Parks departments have volunteers who monitor parks, including wetlands, lakes, etc., to protect ecosystems.[31] From time to time, parks and hiking trails are closed to conserve or restore ecosystems.[32] Traditionally, Boulder has avoided using chemical pesticides to control the insect population. However, with the threat of West Nile virus, the city began an integrative plan[33] to control the mosquito population in 2003 that includes chemical pesticides. Residents can opt out of the program by contacting the city and asking that their areas not be sprayed.[34] Under Boulder law, exterminating prairie dogs requires a permit.[35] In 2005, the city experimented with using goats for weed control in environmentally sensitive areas. Goats naturally consume diffuse knapweed and Canada thistle, and although the program was not as effective as it was hoped, goats will still be considered in future weed control projects. In 2010, goats were used to keep weeds under control at the Boulder Reservoir.[36] The city's Open Space and Mountain Parks department manages approximately 8,000 acres (32 km2) of protected forest land west of the city, in accordance with a 1999 Forest Ecosystem Management Plan. The plan aims to maintain or enhance native plant and animal species, their communities, the ecological processes that sustain them and to reduce the wildfire risk to forest and human communities.[37] Climate

Boulder has a temperate climate typical for much of the state and receives many sunny or mostly sunny days each year. Boulder is considered semi-arid (Köppen: BSk) or humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa) within the Köppen climate classification due to its relatively high yearly precipitation and average temperatures remaining above 32 °F (0 °C) year-round.[38][39][40][41] Winter conditions range from generally mild to the occasional bitterly cold. Highs average in the mid to upper 40s °F (7–9 °C). There are 4.6 nights annually where the temperature drops to 0 °F (−18 °C). Because of orographic lift, the mountains to the west often dry out the air passing over the Front Range, shielding the city from precipitation in winter, though heavy snowfalls may occur. Snowfall averages 88 inches (220 cm) per season. Snow depth is usually shallow. Due to the high elevation, a strong warming sun can quickly melt snow cover during the day and Chinook winds bring rapid warm-ups throughout the winter months.[42] Summers are warm, with frequent afternoon thunderstorms. There are roughly 30 days of 90 °F (32 °C) or above each year.[42] Diurnal temperature variation is typically large due to the high elevation and semi-arid climate. Daytime highs are generally cooler than those of most Colorado cities with similar elevations. The highest recorded temperature of 104 °F (40 °C) was on June 25, 2012.[43] The record low was −33 °F (−36 °C) on January 17, 1930. The coldest high temperature, −12 °F (−24 °C), was on February 4, 1989. The warmest overnight low was on July 20, 1998, with a temperature of 82 °F (28 °C)[44]

Demographics Boulder is the principal city of the Boulder, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area. 2020 census

In the 2010 census, there were 97,385 people, 41,302 households, and 16,694 families in the city. The population density was 3,942.7 inhabitants per square mile (1,522.3/km2). There were 43,479 housing units at an average density of 1,760.3 units per square mile (679.7 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.0% White, 0.9% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 4.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.2% some other race, and 2.6% from two or more races. 8.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[50] There were 41,302 households, of which 19.1% had children under 18 living with them, 32.2% were headed by married couples living together, 5.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 59.6% were non-families. 35.8% of all households comprised individuals, and 7.1% were someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.16, and the average family size was 2.84.[50] Boulder's population is younger than the national average, largely due to the presence of university students. The median age at the 2010 census was 28.7 years compared to the U.S. median of 37.2 years. In Boulder, 13.9% of the residents were younger than 18, 29.1% from 18 to 24, 27.6% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 8.9% were 65 or older. For every 100 females, there were 105.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and older, there were 106.2 males.[50] In 2011, the estimated median household income in Boulder was $57,112, and the median family income was $113,681. Male full-time workers had a median income of $71,993 versus $47,574 for females. The per capita income for the city was $37,600. 24.8% of the population and 7.6% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 17.4% of those under 18 and 6.0% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[51] Economy In 2010, the Boulder MSA had a gross metropolitan product of $18.3 billion, the 110th largest metropolitan economy in the United States.[52] In 2007, Boulder became the first city in the United States to levy a carbon tax.[53] In 2013, Boulder appeared on Forbes magazine's list of Best Places for Business and Careers.[54] Top employersIn the city's 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[55] the top employers are:

Arts and cultureBolder BoulderBoulder has hosted a 10 km road run, the Bolder Boulder, on Memorial Day every year since 1979. The race involves over 50,000 runners, joggers, walkers, and wheelchair racers, making it one of the largest road races in the world. It has the largest non-marathon prize purse in road racing.[56] The race culminates at Folsom Field with a Memorial Day Tribute. The 2007 race featured over 54,000[57] runners, walkers, and wheelchair racers, making it the largest race in the US in which all participants are timed and the fifth largest road race in the world.[58] MusicFounded in 1958, the Boulder Philharmonic Orchestra is a professional orchestra under the leadership of its Music Director Michael Butterman.[59] Founded in 1976 by Giora Bernstein, the Colorado Music Festival presents a summer series of concerts in Chautauqua Auditorium.[60] Founded in 1981, the Boulder Bach Festival is an annual festival celebrating the life, legacy, and music of J.S. Bach. The festival is led by Executive Director Zachary Carrettin and Artistic Director Mina Gajic.[61][62] Founded in 1988, Colorado MahlerFest celebrates the legacy of composer Gustav Mahler through an annual festival. Under Artistic Director Kenneth Woods, The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra draws together young professionals, conservatory and university students, and advanced amateurs. DanceBoulder is home to multiple dance companies and establishments. Boulder Ballet was founded by former American Ballet Theatre dancer Larry Boyette in the 1970s as part of the Ballet Arts Studios.[63] Lemon Sponge Cake Contemporary Ballet was founded in 2004 by Robert Sher-Machherndl, former principal dancer of the Dutch National Ballet and Bavarian State Ballet.[64] Conference on World AffairsThe Conference on World Affairs, started in 1948, is an annual one-week conference featuring dozens of discussion panels on contemporary issues.[65] eTownThe internationally syndicated radio program eTown has its headquarters at eTown Hall, at the intersection of 16th and Spruce Streets, in downtown Boulder. Most tapings of this weekly show are done at eTown Hall.[66][67] Polar Bear PlungeBeginning in 1983, hundreds of people head to the Boulder Reservoir on New Year's Day to take part in the annual polar bear plunge.[68] With rescue teams standing by, participants use a variety of techniques to plunge themselves into the freezing reservoir.[69] Once the plunge is complete, swimmers retreat to hot tubs on the reservoir beach to revive themselves from the cold.[citation needed] Naked Pumpkin RunStarting in 1998, dozens of people have taken part in a Halloween run down the city's streets wearing only shoes and a hollowed-out pumpkin on their heads. In 2009, local police threatened participants with charges of indecent exposure, and no naked runners were reported in official newscasts, although a few naked runners were observed by locals. Several illegal attempts, resulting in arrests, have been made to restart the run, but no serious effort has been mounted.[70] 420For several years on April 20, thousands of people gathered on the CU Boulder campus to celebrate 420 and smoke marijuana at and before 4:20 pm.[citation needed] The 2010 head count was officially between 8,000 and 15,000 with some discrepancy between the local papers and the university administrators, who have been thought to have been attempting to downplay the event.[citation needed] Eleven citations were given out whereas the year before there were only two.[71] 2011 was the last year of mass 420 partying at CU[72] as the university, in 2012, took a hard stance against 420 activities, closing the campus to visitors for the day, using smelly fish fertilizer to discourage gathering at the Norlin Quad, and having out-of-town law enforcement agencies help secure the campus.[73] In 2013, April 20 fell on a Saturday. The university continued the 420 party ban and closed the campus to visitors.[74] In 2015 the government conceded and once again opened the park to visitors on April 20.[75] Boulder Cruiser Ride The Happy Thursday Cruiser Ride is a weekly bicycle ride in Boulder Colorado.[76] The Boulder Cruiser Ride grew from a group of friends and friends of friends in the early 90's riding bicycles around Boulder into the social cycling event it is today.[citation needed] Some enthusiasts gather wearing costumes and decorating their bikes; themes are an integral part of the cruiser tradition.[citation needed] Boulder Police began following the cruiser ride as it gained in popularity in the early 2000s.[citation needed] Issues with underage drinking, reckless bicycle riding, and other nuisance complaints led organizers to drop the cruiser ride as a public event.[77] Returning to an underground format, where enthusiasts must become part of the social network before gaining access to event sites, the Boulder Cruiser Ride has continued as a local tradition.[citation needed] On May 30, 2013, over 400 riders attended the Thursday-night Cruiser Ride in honor of "Big Boy", an elk that was shot and killed on New Year's Day by an on-duty[78] Boulder Police officer.[79] Parks and recreation Boulder is surrounded by thousands of acres of recreational open space, conservation easements, and nature preserves. Almost 60%, 35,584 acres (144.00 km2), of open space totaling 61,529 acres (249.00 km2) is open to the public.[80] The unincorporated community of Eldorado Springs, south of Boulder, is home to rock climbing routes.[81] There are climbing routes available in the city open space, including climbing routes of varying difficulty on the Flatirons themselves (traditional protection). Boulder Canyon (sport), directly west of downtown Boulder, has many routes. All three of these areas are affected by seasonal closures for wildlife.[82][83] GovernmentBoulder is a home rule municipality, being self-governing under Article XX of the Constitution of the State of Colorado; Title 31, Article 1, Section 202 of the Colorado Revised Statutes.[84] Politically, Boulder is one of the most liberal and Democratic cities in Colorado when viewed from a Federal and State elections lens. As of July 2019[update], registered voters in Boulder County were 43.4% Democratic, 14.7% Republican, 1.6% in other parties, and 40.3% unaffiliated.[85] By residents and detractors alike, Boulder is often referred to as the "People's Republic of Boulder".[86] In 1974, the Boulder City Council passed Colorado's first ordinance prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. Boulder voters repealed the measure by referendum within a year. In 1975, Boulder County Clerk Clela Rorex was the second in the United States ever to grant same-sex marriage licenses, prior to state laws being passed to prevent such issuance.[87] In July 2019, Boulder declared a "climate emergency" and established target dates[88] for achieving 100% renewable electricity,[89] a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from city organizations and facilities,[90] an increase in local generation of electricity through renewable sources, and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the community.[91] The city created a community-centered process to focus on energy systems, regenerative ecosystems, circular materials economy, land use, and financial systems.[92] EducationPublic schoolsThe Boulder Valley School District (BVSD) administers the public school system in Boulder, aside from a few areas in northeast Boulder, where students attend the St. Vrain Valley School District. Charter schoolsCharter schools within the city of Boulder include Preparatory High School (9–12), Summit Middle School (6–8), and Horizons Alternative School (K–8). Private schoolsA variety of private high schools, middle schools and elementary schools operate in Boulder.   Colleges and universities

Science institutes

MediaBoulder's main daily newspaper, the Daily Camera, was founded in 1890 as the weekly Boulder Camera, and became a daily newspaper in 1891. The Colorado Daily was started in 1892 as a university newspaper for CU Boulder. Following many heated controversies over Colorado Daily's political coverage, it severed its ties to the university in 1971. From 1996 to 2000, the Boulder Planet competed with the Boulder Weekly as a free weekly.[93] Newspaper conglomerate Scripps acquired the Colorado Daily in 2005 after its acquisition of the Camera in 1997, leaving the Boulder Weekly as the only locally owned newspaper in Boulder. Scripps relinquished its 50 percent ownership in both daily papers in early 2009 to Media News Group. Boulder Magazine, a lifestyle magazine, was founded in 1978.[94] Boulder Magazine is published three times per year. Boulder is part of the Denver market for television stations, and it receives many radio stations based in Denver or Ft. Collins. For cable television, Boulder is served by Comcast Cable. The city operates public service Boulder 8 TV on cable (high- and standard-definition), which airs, live-streams and archives council meetings. With its in-house video production facilities, it also produces news, talk and informational programming.[95] Over-the-air television reception is poor in the western part of the city because of interference from mountains. Non-commercial community radio station KGNU was founded in 1978[96] and commercial music station KBCO in 1977. KBCO programs an adult album alternative format and is owned and operated by iHeartMedia. KBCO moved its studios from Boulder to the Denver Tech Center in 2010.[97] It maintains the Boulder license and transmits from atop Eldorado Mountain south of Boulder.[98] KVCU, also known as Radio 1190, is a non-commercial radio station run with the help of university-student volunteers. KVCU started broadcasting in 1998.[99] NPR programming is heard over KCFC 1490 AM, operated by Colorado Public Radio, and simulcasting Denver station KCFR 90.1. KRKS-FM 94.7, owned and operated by Salem Media Group and affiliated with SRN News, offers a Christian talk and teaching format, and has its transmitter located on Lee Hill, northwest of Boulder. The University of Colorado Press, a non-profit co-op of various western universities, publishes academic books, as do Lynne Rienner Publishers, Paradigm Publishers, and Westview Press.[100] Paladin Press book/video publishers and Soldier of Fortune magazine both have their headquarters in Boulder.[101][102] Paladin Press was founded in September 1970 by Peder Lund and Robert K. Brown. In 1974, Lund bought out Brown's share of the press, and Brown founded Soldier of Fortune magazine in 1975.[103] InfrastructureTransportation Since Boulder has operated under residential growth control ordinances since 1976, the growth of employment in the city has far outstripped population growth. Considerable road traffic enters the city each morning and leaves each afternoon, since many employees live in Longmont, Lafayette, Louisville, Broomfield, Westminster, and Denver. Boulder is served by US 36 and a variety of state highways. Parking regulations in Boulder have been explicitly designed to discourage parking by commuters and to encourage the use of mass transit, with mixed results.[104] Over the years, Boulder has made significant investments in the multi-modal network. The city is now well known for its grade-separated bicycle and pedestrian paths, which are integrated into a network of bicycle lanes, cycle tracks, and on-street bicycle routes. Boulder provides a community transit network that connects downtown, the University of Colorado campuses, and local shopping amenities. Boulder has no rail transit. Local and regional shuttle busses are funded by a variety of sources. Due in part to these investments in pedestrian, bicycle, and transit infrastructure, Boulder has been recognized both nationally and internationally for its transportation system.[105] In 2009, the Boulder metropolitan statistical area (MSA) ranked as the fourth highest in the United States for percentage of commuters who biked to work, at 5.4 percent.[106] In 2013, the Boulder MSA ranked as the fourth lowest in the United States for percentage of workers who commuted by private automobile, at 71.9 percent. During the same time period, 11.1 percent of Boulder area workers had no commute whatsoever: they worked out of the home.[107] Bus serviceBoulder has an extensive bus system operated by the Regional Transportation District (RTD). The HOP, SKIP, JUMP, Bound, DASH and Stampede routes run throughout the city and connect to nearby communities with departures every ten minutes during peak hours, Monday-Friday. Other routes, such as the 204, 205, 206, 208 and 209 depart every 15 to 30 minutes. Regional routes, traveling between nearby cities such as Longmont (BOLT, J), Golden (GS), and Denver (Flatiron Flyer,[108] a bus rapid transit route), as well as Denver International Airport (AB), are also available. There are over 100 scheduled daily bus trips on seven routes that run between Boulder and Denver on weekdays.[109] RailroadsFreight service is provided by Union Pacific and BNSF. Currently there is no intercity passenger service. The last remaining services connecting the Front Range cities ceased with the formation of Amtrak in 1971. Future transit plansFront Range Passenger Rail is a current proposal (as of 2023) to link the cities from Pueblo in the south, north to Fort Collins and possibly to Cheyenne, Wyoming.[110] A 41-mile (66 km) RTD commuter rail route called the Northwest Rail Line, also known as the B Line, is proposed to run from Denver through Boulder to Longmont, with stops in major communities along the way. The Boulder station is to be north of Pearl Street and east of 30th Street. At one time this commuter rail service was scheduled to commence in 2014, but major delays have ensued. In 2016, an initial 6-mile (9.7 km) segment opened, reaching from downtown Denver to southern Westminster at Westminster Station.[111] The remaining 35 miles (56 km) of the Northwest Rail Line is planned to be completed by 2044, depending upon funding.[112] These future transit plans, as well as the current Flatiron Flyer Bus Rapid Transit route, are part of FasTracks, an RTD transit improvement plan funded by a 0.4% increase in the sales tax throughout the Denver metro area. RTD, the developer of FasTracks, is partnering with the city of Boulder to plan a transit-oriented development near Pearl and 33rd Streets in association with the proposed Boulder commuter rail station. The development is to feature the Boulder Railroad Depot, already relocated to that site, which may be returned to a transit-related use. CyclingBoulder, well known for its bicycle culture, has hundreds of miles of bicycle-pedestrian paths, lanes, and routes that interconnect to create a renowned network of bikeways usable year-round. Boulder has 74 bike and pedestrian underpasses that facilitate safer and uninterrupted travel throughout much of the city. The city offers a route-finding website that allows users to map personalized bike routes around the city,[113] and is one of five communities to have received a "Platinum Bicycle Friendly Community" rating from the League of American Bicyclists.[114] The headquarters of the free and non-obligatory hospitality exchange network for cyclists, Warm Showers, is based in Boulder.[115] In May 2011, B-cycle bike-sharing opened in Boulder with 100 red bikes and 12 stations.[116] AirportBoulder Municipal Airport is located 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of central Boulder, is owned by the City of Boulder and is used exclusively for general aviation, with most traffic consisting of single-engine airplanes and glider aircraft.[117] Notable people

In popular culture Woody Allen's film Sleeper (1973) was filmed on location in Boulder.[119] Some houses and the Mesa Laboratory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, designed by I. M. Pei, were used in the film. Boulder was a setting for Stephen King's book The Stand (1978), as the gathering point for some of the survivors of the superflu. King lived in Boulder for a little less than a year, beginning in the autumn of 1974, and wrote The Shining (1977) during this period.[120] The television sitcom Mork & Mindy (1978–1982) was set in Boulder, with 1619 Pine St. serving as the exterior shot of Mindy's home.[121] The New York Deli, a now closed restaurant in the Pearl Street Mall, was also featured prominently in the series.[122] In the American version of the television sitcom The Office, the character Michael Scott leaves the show in season 7 and moves with his fiancée to Boulder.[123] "Boulder to Birmingham" is a song written by Emmylou Harris and Bill Danoff which first appeared on Harris's 1975 album Pieces of the Sky. It has served as something of a signature tune for the artist and recounts her feelings of grief in the years following the death of country rock star and mentor Gram Parsons.[124] The Comedy Central television show Broad City ends with the protagonist, Abby, moving to Boulder for an art fellowship.[125] Significant parts of the 2006 movie Catch and Release were filmed in Boulder, and includes many well-known Boulder institutions such as Celestial Seasonings, the Boulder Farmer's Market, and Pearl Street Mall.[126] Sister citiesBoulder's sister cities are:[127]

Landmarks representing Boulder's connection with its various sister cities can be found throughout the city. Boulder's Sister City Plaza – dedicated on May 17, 2007 – is located on the east lawn of Boulder's Municipal Building. The plaza was built to honor all of Boulder's sister city relationships.[128] The Dushanbe Tea House is located on 13th Street just south of the Pearl Street Mall. Dushanbe presented its distinctive tea house as a gift to Boulder in 1987. It was completed in Tajikistan in 1990 and then shipped to Boulder, where it was reassembled and opened to the public in 1998.[129] A mural representing the relationship between Boulder and Mante, Mexico, was dedicated in August 2001. The mural, which was painted by Mante muralist Florian Lopez, is located on the north-facing wall of the Dairy Center for the Performing Arts.[130] See also

References

Further reading

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||