|

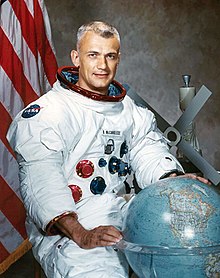

Bruce McCandless II

Bruce McCandless II (born Byron Willis McCandless;[1] June 8, 1937 – December 21, 2017) was an American Navy officer and aviator, electrical engineer, and NASA astronaut. In 1984, during the first of his two Space Shuttle missions, he completed the first untethered spacewalk by using the Manned Maneuvering Unit. Early life and educationByron Willis McCandless[1] was born on June 8, 1937, in Boston, Massachusetts.[2] A third-generation U.S. Navy officer, McCandless was the son of Bruce McCandless and grandson of Willis W. Bradley, both Medal of Honor recipients. His mother changed his name on June 6, 1938, to Bruce McCandless II.[1] He graduated from Woodrow Wilson Senior High School, Long Beach, California, in 1954.[2] In 1958, he received a B.S. from the United States Naval Academy, graduating second, behind future National Security Advisor John Poindexter, in a class of 899 that also included John McCain.[2] During his professional career, he also received an M.S. in electrical engineering from Stanford University in 1965 and an M.B.A. from the University of Houston–Clear Lake in 1987.[2] United States NavyFollowing his commissioning, McCandless received flight training from the Naval Air Training Command at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, and Naval Air Station Kingsville, Texas.[2] In March 1960, he was designated a United States Naval Aviator and proceeded to Naval Air Station Key West for weapons system and carrier landing training in the Douglas F4D-1 Skyray.[2] Between December 1960 and February 1964, he was assigned to Fighter Squadron 102 (VF-102), flying the Skyray and the McDonnell Douglas F-4B Phantom II. He saw duty aboard USS Forrestal and USS Enterprise, including the latter's participation in the Cuban Missile Crisis.[2] For three months in early 1964, he was an instrument flight instructor in Attack Squadron 43 (VA-43) at Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia, and then reported to the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps unit at Stanford University for graduate studies in electrical engineering.[2] During Naval service he gained flying proficiency in the Lockheed T-33B Shooting Star, Northrop T-38A Talon, McDonnell Douglas F-4B Phantom II, Douglas F4D Skyray, Grumman F11F Tiger, Grumman F9F Cougar, Lockheed T-1 Seastar, and Beechcraft T-34B Mentor, and the Bell 47G helicopter.[2] He logged more than 5,200 hours flying time, including 5,000 hours in jet aircraft.[3] NASA career At the age of 28, McCandless was selected as the youngest member of NASA Astronaut Group 5 (jokingly labeled the "Original Nineteen" by John W. Young) in April 1966.[4] According to space historian Matthew Hersch, McCandless and Group 5 colleague Don L. Lind were "effectively treated ... as scientist-astronauts" (akin to those selected in the fourth and sixth groups) by NASA due to their substantial scientific experience, an implicit reflection of their lack of the test pilot experience highly valued by Deke Slayton and other NASA managers at the time; this would ultimately delay their progression in the flight rotation.[5] He served as mission control capsule communicator (CAPCOM) on Apollo 11 during the launch and during the first lunar moonwalk (EVA) by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin before joining the astronaut support crew for the Apollo 14 mission, on which he doubled as a CAPCOM.[6] Thereafter, McCandless was reassigned to the Skylab program, where he received his first crew assignment as backup pilot for the space station's first crewed mission alongside backup commander Rusty Schweickart and backup science pilot Story Musgrave.[7] Following this assignment, he again served as a CAPCOM on Skylab 3 and Skylab 4. Notably, McCandless was a co-investigator on the M-509 astronaut maneuvering unit experiment that was flown on Skylab; this eventually led to his collaboration on the development of the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) used during Space Shuttle EVAs.[8] Although he was classified as a Shuttle pilot until 1983, McCandless ultimately chose to work on the MMU as a mission specialist due to the prestige of the program (which ensured a flight assignment) and his lack of test pilot experience.[9] He was responsible for crew inputs to the development of hardware and procedures for the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), Hubble Space Telescope, the Solar Maximum Repair Mission, and the International Space Station program.[3] McCandless logged over 312 hours in space, including four hours of MMU flight time.[3] He flew as a mission specialist on STS-41-B and STS-31.[10] STS-41-BMcCandless in 1982 Challenger launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on February 3, 1984. The flight deployed two communications satellites, and flight-tested rendezvous sensors and computer programs for the first time.[3] This mission marked the first checkout of the MMU and Manipulator Foot Restraint (MFR). McCandless made the first untethered free flight on each of the two MMUs carried on board, thereby becoming the first person to make an untethered spacewalk.[3] He described the experience:[11]

McCandless's first EVA lasted 6 hours and 17 minutes. The second EVA (in which Stewart used the MMU) lasted 5 hours and 55 minutes.[12] On February 11, 1984, after eight days in orbit, Challenger made the first landing on the runway at Kennedy Space Center.[3] STS-31On this five-day Discovery flight, launched on April 24, 1990, from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the crew deployed the Hubble Space Telescope from their record-setting altitude of 380 miles (610 km).[3] During the deployment of Hubble, one of the observatory's solar arrays stopped as it unfurled. While ground controllers searched for a way to command HST to unreel the solar array, Mission Specialists McCandless and Kathryn D. Sullivan began preparing for a contingency spacewalk in the event that the array could not be deployed through ground control. The array eventually came free and unfurled through ground control, while McCandless and Sullivan were pre-breathing inside the partially depressurized airlock.[13] Discovery landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, on April 29, 1990.[3] After NASAAfter retiring from NASA in 1990, McCandless worked for Lockheed Martin Space Systems.[11] Organizations

He was a fellow of the American Astronautical Society and former president of the Houston Audubon Society.[3] Awards and honors

He was awarded a patent for the design of a tool tethering system that was used during Space Shuttle spacewalks.[3] Personal life McCandless was married to Bernice Doyle McCandless (1937–2014)[17] for 53 years, and the couple had two children. His recreational interests included electronics, photography, scuba diving, and flying. He also enjoyed cross-country skiing.[3] In an August 2005 Smithsonian magazine article about the MMU photo, McCandless is quoted as saying that the subject's anonymity is its best feature. "I have the sun visor down, so you can't see my face, and that means it could be anybody in there. It's sort of a representation not of Bruce McCandless, but mankind."[18] On September 30, 2010, McCandless launched a lawsuit against British singer Dido for unauthorized use of a photo of his 1984 space flight for the album art of her 2008 album Safe Trip Home, which showed McCandless "free flying" about 320 feet away from the Space Shuttle Challenger.[19] The lawsuit, which also named Sony Corp.'s Sony Music Entertainment and Getty Images as defendants, did not allege copyright infringement but infringement of his persona.[20][21] The action was settled amicably on January 14, 2011.[22] McCandless wrote the foreword to the book Live TV from Orbit by Dwight Steven-Boniecki.[23] McCandless died on December 21, 2017, at age 80.[24] He was survived by his second wife, Ellen Shields McCandless, two children and two grandchildren.[25] McCandless is buried at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery at Annapolis on January 16, 2018. McCandless' son, author Bruce McCandless III, wrote about the journey leading to the first untethered spacewalk in the 2021 book Wonders All Around: The Incredible True Story of Astronaut Bruce McCandless II and the First Untethered Flight in Space. LegacyJohn McCain, who graduated from the United States Naval Academy with McCandless in the Class of 1958, stated after McCandless' death:[11]

Lockheed Martin later developed the McCandless Lunar Lander and named it after him. This honored him as an esteemed employee of the company, and also the fact that the MMU spacewalk was facilitated by the jetpack developed by Lockheed Martin. See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Bruce McCandless II. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||