|

Capital punishment in France

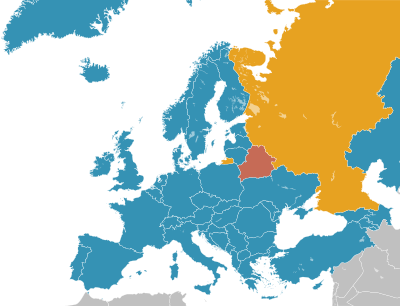

Abolished for all offences Abolished in practice Retains capital punishment Capital punishment in France (French: peine de mort en France) is banned by Article 66-1 of the Constitution of the French Republic, voted as a constitutional amendment by the Congress of the French Parliament on 19 February 2007 and simply stating "No one can be sentenced to the death penalty" (French: Nul ne peut être condamné à la peine de mort). The death penalty was already declared illegal on 9 October 1981 when President François Mitterrand signed a law prohibiting the judicial system from using it and commuting the sentences of the seven people on death row to life imprisonment. The last execution took place by guillotine, being the main legal method since the French Revolution; Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian citizen convicted of torture and murder on French soil, was put to death in September 1977 in Marseille.[1] Major French death penalty abolitionists across time have included philosopher Voltaire; poet Victor Hugo; politicians Léon Gambetta, Jean Jaurès and Aristide Briand; and writers Alphonse de Lamartine and Albert Camus. HistoryAncien Régime Prior to 1791, under the Ancien Régime, there existed a variety of means of capital punishment in France, depending on the crime and the status of the condemned person:

On 6 July 1750, Jean Diot and Bruno Lenoir were strangled and burned at the stake in Place de Grève for sodomy, the last known execution for sodomy in France.[2] Also in 1750, Jacques Ferron was either hanged or burned at the stake in Vanvres for bestiality, the last known execution for bestiality in France.[3][4][5] Adoption of the guillotine  The first campaign towards the abolition of the death penalty began on 30 May 1791, but on 6 October that year the National Assembly refused to pass a law abolishing the death penalty. However, they did abolish torture, and also declared that there would now be only one method of execution: 'Tout condamné à mort aura la tête tranchée' (All condemned to death will have their heads cut off). In 1789, physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed that all executions be carried out by a simple and painless mechanism, which led to the development and eventual adoption of the guillotine. Beheading had previously been reserved only for nobles and carried out manually by handheld axes or blades; commoners would usually be hanged or subjected to more brutal methods. Therefore, the adoption of the guillotine for all criminals regardless of social status not only made executions more efficient and less painful, but it also removed the class divisions in capital punishment altogether. As a result, many felt the device made the death penalty more humane and egalitarian. The guillotine was first used on Nicolas Jacques Pelletier on 25 April 1792. Guillotine usage then spread to other countries such as Germany (where it had been used since before the revolution), Italy, Sweden (used in a single execution), the Netherlands and French colonies in Africa, Canada, French Guiana and French Indochina. Although other governments employed the device, France has executed more people by guillotine than any other nation. Penal Code of 1791On October 6, 1791, the Penal Code of 1791 was enacted, which abolished capital punishment in the Kingdom of France for bestiality, blasphemy, heresy, pederasty, sacrilege, sodomy, and witchcraft.[6][7] 1939 onwards

Public executions were the norm and continued until 1939. From the mid-19th century, the usual time of day for executions changed from around 3 pm to morning and then to dawn. Executions had been carried out in large central public spaces such as market squares but gradually moved towards the local prison. In the early 20th century, the guillotine was set up just outside the prison gates. The last person to be publicly guillotined was six-time murderer Eugen Weidmann who was executed on 17 June 1939 outside the St-Pierre prison in Versailles. Photographs of the execution appeared in the press, and apparently this spectacle led the government to stop public executions and to hold them instead in prison courtyards, such as La Santé Prison in Paris. Following the law, the first to be guillotined inside a prison was Jean Dehaene, who had murdered his estranged wife and father-in-law, executed on 19 July 1939 at St-Brieuc. The 1940s and the wartime period saw an increase in the number of executions, including the first executions of women since the 19th century.[citation needed] Marie-Louise Giraud was executed on 30 July 1943 for being an abortion provider, which was labeled a crime against state security.[citation needed] In the 1950s to the 1970s, the number of executions steadily decreased, with for example President Georges Pompidou, between 1969 and 1974, giving clemency to all but three people out of the fifteen sentenced to death. President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing oversaw the last executions.[citation needed] Up to 1981, the French penal code[8] stated that:

In addition, crimes such as treason, espionage, insurrection, piracy, aggravated murder, kidnapping with torture, felonies committed with the use of torture, setting a bomb in a street, arson of a dwelling house, and armed robbery made their authors liable to the death penalty; moreover, committing some military offenses such as mutiny or desertion or being accomplice or attempting to commit a capital felony were also capital offenses. ClemencyThe right to commute death sentences belonged exclusively to the President of the Republic, whereas it had belonged exclusively to the monarch in earlier ages. President Charles de Gaulle, who supported capital punishment, commuted 24 death sentences. During his term of office, 35 people were guillotined, 4 others executed by firing squad for crimes against the security of the state, while 3 other were reprieved by amnesty in 1968. The last of those executed by firing squad was OAS member Lt. Colonel Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, who was an organizer of the infamous assassination attempt on de Gaulle in 1962. No executions took place during two-term acting President Alain Poher, neither in 1969 following De Gaulle's resignation, nor in 1974 following Pompidou's death. President Georges Pompidou, who opposed capital punishment, commuted all but three death sentences imposed during his term. President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who stated that he "felt a deep aversion to the death penalty", also commuted all but three death sentences. During his presidency, the last three capital executions in France took place. AmnestyParliament (rather than the executive) held the power to grant amnesty for death sentences. One example of general amnesty for all people sentenced to death and awaiting execution took place in 1959 after de Gaulle's inauguration when an Act of Parliament commuted all such sentences.[9] AbolitionThe first official debate on the death penalty in France took place on 30 May 1791 with the presentation of a bill aimed at abolishing it. The advocate was Louis-Michel Lepeletier of Saint-Fargeau and revolutionary leader Maximilien de Robespierre supported the bill. However, the National Constituent Assembly, on 6 October 1791, refused to abolish the death penalty. Soon after, tens of thousands of people of various social classes would be executed by guillotine during the Reign of Terror. On 26 October 1795, the National Convention abolished capital punishment, but only to signify the day of general peace. The death penalty was reinstated on 12 February 1810, under Emperor Napoleon I, in the French Imperial Penal Code. In 1848, the provisional government of the French Second Republic, established by the February Revolution, decreed the abolition of the death penalty for political crimes.[10] President Armand Fallières, a supporter of abolition, systematically pardoned every convict condemned to death over the first three years of his term (1906–1913). In 1906 the Commission of the Budget of the Chamber of Deputies voted for withdrawing funding for the guillotine, with the aim of stopping the execution procedure. On 3 July 1908 the Keeper of the Seals, Aristide Briand, submitted a draft law to the Deputies, dated November 1906, on the abolition of the death penalty. Despite the support of Jean Jaurès, the bill was rejected on 8 December by 330 votes to 201. Under the pro-Nazi Vichy Regime, Marshal Pétain refused to pardon five women due to be guillotined; no woman had been guillotined in France in over five decades. Pétain was himself sentenced to death following the overthrow of the Vichy Regime, but General Charles de Gaulle commuted Pétain's sentence to life imprisonment on the grounds of his old age (89 years), as well as his previous military duty during the First World War. Other Vichy officials, including notably Pierre Laval, were not so fortunate and were shot. Under Vincent Auriol's presidency, three more women were beheaded, one in Algeria and two in France. The last Frenchwoman to be beheaded (Germaine Leloy-Godefroy) was executed in Angers in 1949. In 1963, Lt. Colonel Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry became the last person to be executed by a firing squad. Defended by lawyer Robert Badinter, child murderer Patrick Henry narrowly escaped being condemned to death on 20 January 1977, and numerous newspapers predicted the end of the death penalty. On 10 September 1977, Hamida Djandoubi was guillotined and became both the last person executed in France as well as the last person executed by beheading in the Western world, and by any means in Western Europe. On 18 September 1981, Badinter—the new Minister of Justice—proposed the final abolition of the death penalty in the National Assembly, the same day as the newly-elected socialist president François Mitterrand backed his efforts, and the National Assembly finally pushed abolition through that same year. Badinter had been a longtime opponent of capital punishment and the defense attorney of some of the last men to be executed. Abolition process in 1981

Current statusToday, the death penalty has been abolished in France. Although a few modern-day French politicians (notably the far-right Front national[1] former leader Jean-Marie Le Pen) advocate restoring the death penalty, its re-establishment would not be possible without the unilateral French rejection of several international treaties. (Repudiation of international treaties is not unknown to the French system, as France renounced its obligations under the NATO treaty in 1966, though it rejoined the pact in 2009.[17]) On 20 December 1985, France ratified Additional Protocol number 6 to the European Convention to Safeguard Human Rights and fundamental liberties. This prevents France from re-establishing the death penalty, except in times of war or by denouncing the Convention. On 21 June 2001, Jacques Chirac sent a letter to the association "Ensemble" saying he was against the death penalty: "It's a fight we have to lead with determination and conviction, because no justice is infallible and each execution can kill an innocent; because nothing can legitimise the execution of minors or of people suffering from mental deficiencies; because death can never constitute an act of justice." On 3 May 2002, France and 30 other countries signed Protocol number 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights. This forbids the death penalty in all circumstances, even in times of war. It went into effect on 1 July 2003, after having been ratified by 10 states. Despite these efforts, in 2004, a law proposition (number 1521[18]) was placed before the French National Assembly, suggesting re-establishment of the death penalty for terrorist acts. The bill was not adopted. On 3 January 2006, Jacques Chirac announced a revision of the Constitution aimed at writing out the death penalty. (On the previous 13 October, the Constitutional Council had deemed the ratification of the Second Optional Protocol to the international pact necessitated such a revision of the Constitution. The protocol concerned civil and political rights aimed at abolishing the death penalty.) On 19 February 2007, the Congress of the French Parliament (the National Assembly and the Senate, reunited for the day) voted overwhelmingly for a modification of the Constitution stating that "no one can be sentenced to the death penalty." There were 828 votes for the modification, and 26 against. The amendment entered the Constitution on 23 February. Variations in French opinionDuring the 20th century, French opinion on the death penalty has greatly changed, as many polls have showed large differences from one time to another.

Executions from 1958 to abolitionThe following people were executed during the Fifth Republic (between 1959 and 1977), making them the last executed people in France.[24]

Notable opponents

Notable advocates

References

Bibliography

|