|

Chan Chan

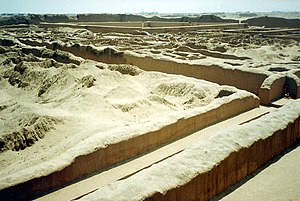

Chan Chan (Spanish pronunciation: [tʃaɲ.'tʃaŋ]), sometimes itself called Chimor, was the capital city of the Chimor kingdom. It was the largest city of the pre-Columbian era in South America.[1] It is now an archeological site in the department of La Libertad five kilometers (3.1 mi) west of Trujillo, Peru.[2] Chan Chan is located in the mouth of the Moche Valley[3] and was the capital of the historical empire of the Chimor from 900 to 1470,[4] when they were defeated and incorporated into the Inca Empire.[5] Chimor, a conquest state,[3] developed from the Chimú culture which established itself along the Peruvian coast around 900 CE.[6] Chan Chan is in a particularly arid section of the coastal desert of northern Peru.[7] Due to the lack of rain in this area, the major source of nonsalted water for Chan Chan is in the form of rivers carrying surface runoff from the Andes.[4] This runoff allows for control of land and water through irrigation systems. The city of Chan Chan spanned 20 square kilometers (7.7 sq mi; 4,900 acres) and had a dense urban center of six square kilometers (2.3 sq mi; 1,500 acres) which contained extravagant ciudadelas.[3] Ciudadelas were large architectural masterpieces which housed plazas, storerooms, and burial platforms for the royals.[8] The splendor of these ciudadelas suggests their association with the royal class.[8] Housing for the lower classes of Chan Chan's hierarchical society are known as small, irregular agglutinated rooms (SIARs).[8] Because the lower classes were often artisans whose role in the empire was to produce crafts, many of these SIARs were used as workshops.[8] EtymologyThe original meaning and the language of origin of the place name Chan Chan remain unresolved issues among specialists. Among others, scholars such as Ernst Middendorf, Jorge Zevallos Quiñones, Rodolfo Cerrón-Palomino and Matthias Urban have dealt with the question. The puzzle is made difficult by the erratic nature of its written record in colonial documents and by the linguistic situation of the pre-Hispanic North Peruvian coast. As is known, the Trujillo region presented the Mochica, Quingnam, Culli and Quechua languages, among others, of which only Mochica and Quechua are sufficiently documented. Regarding the variation in its written record, the toponym appears for the first time in documentation written as 'Cauchan' in the foundation act of the Trujillo town council of 1536.[9] It has also been proposed that the name 'Canda' offered by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo to refer to Trujillo is another written variant of the modern Chan Chan.[10] The form 'Chanchan' only appears in documentation in a stable manner from the mid-17th century onwards. According to the review of antecedents offered by Urban, there have been three previous etymological proposals for the toponym, two of which can be considered completely fanciful and unmotivated. The etymologies of H. Bauman as 'city of snakes', who unmotivatedly appeals to Mesoamerican languages, and that of J. Kimmich as 'city of the moon', who unmotivatedly appeals to a Cariban word for 'moon', deserve the latter qualification. The third etymological hypothesis was postulated by German scholar Ernst Middendorf, who offers the Mochica noun xllang 'sun' as etym and finds in the toponym a reduplication of that root.[11] Without being convinced by any of these previous proposals, Urban is inclined to the tentative attribution of the toponym to the extinct Quingnam language already proposed by Zevallos Quiñones in the XXth century. According to these authors, although it is not possible to offer an etym nor a primary meaning for the place name, the quingnam attribution is justified by the fact that this was the language of the kingdom of Chimor and by the similarity in its apparent structure with other regional toponyms and anthroponyms also apparently constituted by the reduplication of two monosyllabic roots.[12] Urban concludes that

More recently, linguist Rodolfo Cerrón-Palomino has proposed a Quechua etymology for the toponym. According to his hypothesis, both the form 'Chanchan' and the variants 'Cauchan' and 'Canda' may well be explained by a Quechua etym kanĉa 'corral, fence, fenced place' and the Quechumaran toponymic morpheme *-n (of probable Aymara etymology). Thus, the current pronunciation would be the product of an "orthographic trap", since originally the <ch> would have been used to represent the sound of a voiceless velar stop [k] at the beginning of the word. Originally, the toponym would have been *kanĉa-n(i) '(place) where fences/ corrals abound'. According to this proposal, the toponym would be neither Mochica nor Quingnam, nor would it be so ancient in time.[13] However, Urban has rejected Cerrón-Palomino's hypothesis as implausible and ratified his previous conclusions.[14] HistoryChan Chan is believed to have been constructed around 850 AD by the Chimú.[15] It was the Chimor empire capital city with an estimated population of 40,000–60,000 people.[8] After the Inca conquered the Chimú around 1470 AD, Chan Chan fell into decline.[8] the Incas used a system called the "Mitma system of ethnic dispersion" which separated the chimú civilians into places already recently conquered by the Inca. A little over 60 years later in 1535 AD, Francisco Pizarro founded the Spanish city of Trujillo which pushed Chan Chan further into the shadows.[8] While no longer a teeming capital city, Chan Chan was still well known for its great riches and was consequently looted by the Spaniards.[8] An indication of the great Chimú wealth is seen in a sixteenth-century list of items looted from a burial tomb in Chan Chan; a treasure equivalent to 80,000 pesos of gold was recovered (nearly $5,000,000 US dollars in gold).[8] In 1969, Michael Moseley and Carol J. Mackey began excavations of Chan Chan; today these excavations continue under the Peruvian Instituto Nacional de Cultura.[15] Conservation planIn 1998, The "Master Plan for Conservation and Management of the Chan Chan Archeological Complex" was drawn up by the Freedom National Culture Institute of Peru with contributions from the World Heritage Foundation – WHR, ICCROM, and GCI. The plan was approved by the Peruvian Government.[16] Methods of conservation include reinforcement and stabilization of structures of main buildings and around the Tschudi Palace, using a blend of traditional and modern engineering techniques.[17] Chan Chan currently has 46 points of critical damage, though the site's total damage far exceeds these points. The regional government of La Libertad is funding conservation efforts at these points. UNESCO World Heritage Site On 28 November 1986, UNESCO designated Chan Chan as a World Heritage Site,[18] and placed it on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The World Heritage Committee's initial recommendations included taking the appropriate measures for conservation, restoration, and management; halting any excavation that did not have accompanying conservation measures; and mitigation of plundering. A Pan-American Course on the Conservation and Management of Earthen Architectural and Archaeological Heritage was funded by many institutes coming together, including ICCROM, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Government of Peru.[17] Archeologists have been trying to protect this city in many ways. They are trying to create rain coverings over the buildings to protect them from the rain and save the adobe buildings that are deteriorating. They have also been trying to create new drainage systems to drain the rainwater faster.[19] Chan Chan has been on the world heritage danger list since 1986. since 2000 they have implemented safety measures that include documentation of everything, public management, and an emergency and disaster plan.[20] Archeological site The archaeological site covers an area of approximately 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi), being considered the largest adobe city in the Americas and the second in the world. The walled compounds (palaces) that make up the metropolis are those in the following table. Recently, archaeologist have given Mochica names to such compounds, despite Chimor having spoken other language than Mochica. This has been criticized as a denial of local history.[21]

Walled compound TschudiThe walled complex "Tschudi" is the greatest in illustration of the importance of water, particularly of the sea, and of the cult that surrounded it in the Chimu culture. The high reliefs of the walls represent fish, directed towards the north and the south (what can be interpreted as representation of the two currents that mark the Peruvian coast: that of Humboldt, cold, that comes from the south and the one of El Niño, hot, that comes from the north), waves, rombito (fishing nets), as well as pelicans and anzumitos (mixture of sea lion and otter). This coastal society was governed by the powerful Chimucapac and was united by the force of a social control originated in the necessity of a strict management of the water, as well as by the external threats. The "Tschudi" complex had a single entrance and high walls up to twelve meters for a better defense, and was wider at its bases (five meters) than at its summits (one meter), in anticipation of possible earthquakes on the seismic coast. BuildingsChan Chan has many different types of buildings many of which have been destroyed. Many of the buildings included temples, houses, reservoirs and even funeral platforms. Many of the buildings consisted of ocean like designs such as fish, birds, waves and more. The way the Chimú utilized the space is astonishing. They build the building mostly in a rectangular or square shape through tight spaces.[22] The city also consisted of 10 citadels yet only 4 have been recovered. This means the city of Chan Chan had 10 rulers, the Chimú were very adamant on the "Great Lord on top". The culture lived in a classist society where the rulers and gods were on top then it went all the way down to servants. A citadels complex is usually 40 feet tall and built with only one entrance. It was a palace type place with beautiful decorations and was built for a "god or ruler".[23] Workers and people Chan Chan held many different types of workers and people. They lived in a classist society where rulers and gods came first and servants last. The city consisted of nobles, farmers, fishers, trader, servants, and many more. They had many craftsmen in the city who designed beautiful fabrics, pots, and ceramics.[24] The chimú civilians had a belief that the sun created three eggs, gold for the ruler and the elite, silver was for the wives of the rulers and copper was for anyone else not in those two categories. The elite were the ones who lived in the citadels. the rest of the civilians lived in small home that doubled as their workshops.[25] Although they were an agriculture city, the Chimú people did excellent jobs on their pottery and textiles and is what they are most famous for. They designed many beautiful pieces of artwork, some of which is still around today.[25] Religion and culture The Chimu have 10 citadels, but the Tschudi is the only one that tourists are allowed into. It is believed that Tschudi was built in honor of the Chimú God of the sea whose name in quingnam is unknown. This is believed because of the many ocean-related figures in the building. There was a pond in the middle of the building that was used for religious ceremonies, fertility, and even worshipping water. Something that the Chimu civilians worship very much is the ocean, they are directly next to the Pacific Ocean and get most of their food through it. They also relied very much on their irrigation system, so they believe that worshipping gods related to the ocean is important.[23] The Chan Chan civilians supposedly spoke the language "quingnam". Once the Inca took over this language was completely wiped out and is currently an extinct language. There's very little documented on the quingnam language. unfortunately, there is no way for us to confirm how this language could have sounded. The Chimú civilian had no writing system where they documented their language. Not only did they not have a documented writing system for their language, but they also had no written system for writing up blueprints or recording measurements. If you look at a photo of Chan Chan, you will notice how all the buildings are built in a distinct order with space between them. Although there was no documentation it is possible and a theory that they kept records called Khipus much like the Inca. Khipus are detailed records that are systems with knotted cords. Khipus can also be used in situations to communicate information.[26] Architecture The city has ten walled ciudadelas which housed ceremonial rooms, burial chambers, temples, reservoirs and residences for the Chimú kings.[8] In addition to the ciudadelas, other compounds present in Chan Chan include courts, or audiencias,[27] small, irregular agglutinated rooms (SIARs) and mounds called huacas.[8] Evidence for the significance of these structures is seen in many funerary ceramics recovered from Chan Chan.[27] Many images seemingly depict structures very similar to audiencias[27] which indicates the cultural importance of architecture to the Chimú people of Chan Chan. Additionally, the construction of these massive architectural feats indicates that there was a large labor force available at Chan Chan.[27] This further supports evidence for a hierarchical structure of society in Chan Chan as it was likely that the construction of this architecture was done by the working class.[27] Chan Chan is triangular, surrounded by 50–60-foot (15–18 m) walls.[28] There are no enclosures opening north because the north-facing walls have the greatest sun exposure, serving to block wind and absorb sunlight where fog is frequent.[15] The tallest walls shelter against south-westerly winds from the coast. The walls are adobe brick[8] covered with a smooth surface into which intricate designs are carved. The two styles of carving design include a realistic representation of subjects such as birds, fish, and small mammals, as well as a more graphic, stylized representation of the same subjects. The carvings at Chan Chan depict crabs, turtles, and nets for catching sea creatures (such as Spondylus. Chan Chan, unlike most coastal ruins in Peru, is very close to the Pacific Ocean.[29] Irrigation Originally the city relied on wells that were around 15 meters deep.[29] To increase the farmland surrounding the city, a vast network of canals diverting water from the Moche river were created.[30] Once these canals were in place, the city had the potential to grow substantially. Many canals to the north were destroyed by a catastrophic flood around 1100 CE, which was the key motivation for the Chimú to refocus their economy to one rooted in foreign resources rather than in subsistence farming.[29] Chan Chan's irrigations systems were one of the main reasons they ended up being conquered by the Incas. Since the canals could run as long as 20 miles down the mountain of the Moche Vally River into Chan Chan, the Incas ended up cutting off their irrigation system which left them with dying crops from lack of water. ThreatsThe ancient structures of Chan Chan are threatened by erosion due to changes in weather patterns — heavy rains, flooding, and strong winds.[31][32] In particular, the city is severely threatened by storms from El Niño, which causes increased precipitation and flooding on the Peruvian coast.[7] Chan Chan is the largest mud city in the world, and its fragile material is cause for concern. The heavy rains of El Niño damages the base of Chan Chan's structures. Increased rain also leads to increased humidity, and as humidity gathers in the bases of these structures, salt contamination and vegetation growth can occur, which further damage the integrity of Chan Chan's foundations. Global warming will only further these negative impacts, as some models suggest climate change facilitates increased precipitation.[33] Recent archaeological conservation surveys The archaeological site at Chan Chan is under constant and severe threat of ruin from weathering. Several archaeologists, conservationists, and an array of institutions are working to survey the architecture existing there. Different methods of survey can be utilized but any methodology must be both quick enough to maximize access to extant physical material and accurate enough to document the site effectively.[34] In order to meet these requirements, unmanned aerial vehicles are being utilized. The current state of UAV technology is such that craft consisting of relatively small components combined with lightweight imaging technology can be employed. The possible imaging products include Digital Elevation Models, ortho-photos, and 3 Dimensional Virtual Models.[34] Protective coverings at the site, intended to inhibit the extent of weathering damage to adobe structures, can be a challenge to the use of UAV's. These methods do not contribute to decay of the physical material. These methods also allow archaeologists to have access to the virtual reproductions into the future and foreseeable technological innovations will most likely add to the potential for analysis of the site. The Italian Mission in Peru has been working alongside local archaeologists and excavators at the Chan Chan site since 2002.[34] Roberto Pierdicca of the Polytechnic University of the Marches (Ancona, Italy) conducted imaging missions and compiled a series of results to make conclusions about the scale of the site in 2017. The newest mapwork of the site until this time was created by Harvard University in 1974. Pierdicca's mission mapped a portion of the site known as the Tschudi Palace.[34] His work was presented in the eighth volume of Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage in 2018.[34] The mission employed a Da-Jiang Innovations drone equipped with a Sony Alpha NEX-7 6000 x 3376 pixel resolution camera.[34] The equipment allowed for both nadir imaging (downward vertical) imaging and oblique (angled) imaging. 1856 images were acquired and 1268 of these were used to create a 15 strip photogrammetric model. In order to construct the three-dimensional model, 105 images taken from ground level with a Sony SLT-A77V camera. Multi View Stereo processing was used to combine the overhead images with those from the ground and form the 3D model. This model was validated by archaeologists and is considered to be compliant with both the Seville Principles and the London Charter.[34] These models form a baseline for future combinations of overhead imaging with ground surveys at other sites. The archaeological approach is important for the conservation of sites as it allows the data to exist into the future even as looting occurs and weathering takes place. Between 2016 and 2022, an international project between the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) and the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica (CONCYTEC) was conducted at the site.[35] The work intended to build a 3D Heritage Building Information Model (HBIM) of the Huaca Arco Iris, the largest adobe monumental complex in South America. The huaca is placed chronologically alongside the first structures built at Chan Chan. The time frame of the site's construction was towards the end of the Middle Horizon in the Central Andes. The primary function of the huaca is believed to have been a ceremonial funerary platform. In 1963, the Patrona de Arqueologia of Trujillo carried out a project to restore much of the walls at the site. This initiative refrained from adding any new artistic designs.[35] This work contributes to the Plan Maestro de conservación y manejo del Complejo Arqueologico Chan Chan, a UNESCO required architectural conservation plan created by the Instituto Nacional de Cultura of Peru.[35] Creating 3D models of the Huaca Arco Iris is one major initiative of the Italian Mission in Peru. The baseline methodology for the work was the data-information-knowledge system.[35] The data acquisitional survey was initially conducted using spherical photogrammetry. An inspection of the huaca was carried out in 2018 by the Italian Mission. They uncovered additional brick layers on the outside of the south-eastern wall. A Sony Alpha 77 camera was utilized to capture 43 images. With the help of Metashape software, the team created a 3D textured mesh model of the wall.[35] Combined with 3D meshes of the famous bas-reliefs of the other adobe and brick walls, this model was placed into Rhinoceros software to make 3D models of the wall's architectural components.[35] Colosi et al. reached several conclusions in their work. One conclusion is that consistent monitoring of the huaca and Chan Chan as a whole is necessary for limiting anthropogenic damage. The primary conclusion is that ontology-based Heritage Building Information Models are necessary for the longevity of the physical structures and the collective memory of Chan Chan.[35] Clay and straw mud architecture is believed to be the oldest building method on earth. It is extremely versatile, especially considering any size bricks can be created and used to build any size structure. 180 UNESCO World Heritage are constructed to some degree from mud.[35] An international conference for the theme of adobe architecture took place in Iran in 1972.[35] In 1994, the Getty Center established a course on mud architecture and its conservation at the Museo de Sitio at Chan Chan.[35] See also

Citations

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Chan Chan. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||