|

Churchill War Rooms

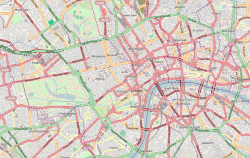

The Churchill War Rooms is a museum in London and one of the five branches of the Imperial War Museum. The museum comprises the Cabinet War Rooms, a historic underground complex that housed a British government command centre throughout the Second World War, and the Churchill Museum, a biographical museum exploring the life of British statesman Winston Churchill. Construction of the Cabinet War Rooms, located beneath the Treasury building in the Whitehall area of Westminster, began in 1938. They became fully operational on 27 August 1939, a week before Britain declared war on Germany. The War Rooms remained in operation throughout the Second World War, before being abandoned in August 1945 after the surrender of Japan. After the war, the historic value of the Cabinet War Rooms was recognised. Their preservation became the responsibility of the Ministry of Works and later the Department for the Environment, during which time very limited numbers of the public were able to visit by appointment. In the early 1980s, the Imperial War Museum was asked to take over the administration of the site, and the Cabinet War Rooms were opened to the public in April 1984. The museum was reopened in 2005 following a major redevelopment as the Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms, but in 2010 this title was shortened to the Churchill War Rooms. ConstructionIn 1936 the Air Ministry, the British government department responsible for the Royal Air Force, believed that in the event of war enemy aerial bombing of London would cause up to 200,000 casualties per week.[2] British government commissions under Warren Fisher and Sir James Rae in 1937 and 1938 considered that key government offices should be dispersed from central London to the suburbs,[nb 1] and nonessential offices to the Midlands or North West.[3] Pending this dispersal, in March 1938 Sir Hastings Ismay, then Deputy Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence, ordered an Office of Works survey of Whitehall to identify a suitable site for a temporary emergency government centre for use during bombing raids.[4] Although it is commonplace for present-day governments to operate such facilities, this was the first time the British government had required one, and as such there was no precedent for how or where it should be built, or what it should contain.[5] In May, as German troops were gathering on the border with Czechoslovakia,[4] the Office concluded the most suitable site was the basement of the New Public Offices (NPO),[6] a government building located on the corner of Horse Guards Road and Great George Street, near Parliament Square. The building now accommodates HM Treasury.[7]  Work to convert the basement of the New Public Offices began, under the supervision of Ismay and Sir Leslie Hollis, in June 1938.[8] The work included installing communications and broadcasting equipment, soundproofing, ventilation and reinforcement.[9] Because the War Rooms are below the level of the River Thames, flood doors and pumps were installed to prevent flooding.[10] Meanwhile, by the summer of 1938 the War Office, Admiralty and Air Ministry had developed the concept of a Central War Room that would facilitate discussion and decision-making between the Chiefs of Staff of the armed forces. As ultimate authority lay with the civilian government the Cabinet, or a smaller War Cabinet, would require close access to senior military figures. This implied accommodation close to the armed forces' Central War Room.[11] In May 1939 it was decided that the Cabinet would be housed within this room.[6] In August 1939, with war imminent and protected government facilities in the suburbs not yet ready, the War Rooms became operational on 27 August 1939, only days before the invasion of Poland on 1 September, and Britain's declaration of war on Germany on 3 September.[4] Wartime useStaff accessed the War Rooms via the main entrance of the NPO, and once inside the building, descended down Staircase 15, entering near to the Churchills' kitchen.[12] During its operational life, two of the Cabinet War Rooms were of particular importance. Once operational, the facility's Map Room was in constant use and manned around the clock by officers of the Royal Navy, British army and Royal Air Force. These officers were responsible for producing a daily intelligence summary for the King, Prime Minister and the military Chiefs of Staff.[13] The other key room was the Cabinet Room, where the Prime Minister and his key advisers would meet with the three Chiefs of Staff – the heads of the army, navy, and air force. Secrecy was paramount, and two sentries were posted outside the door during meetings, which would sometimes continue into the small hours of the morning.[14] Until the opening of the Battle of France, which began on 10 May 1940, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's war cabinet met at the War Rooms only once, in October 1939.[15] Following Winston Churchill's appointment as Prime Minister, Churchill visited the Cabinet Room in May 1940 and declared: 'This is the room from which I will direct the war'.[16] In total 115 Cabinet meetings were held at the Cabinet War Rooms,[17] the last on 28 March 1945, when the German V-weapon bombing campaign came to an end.[18]  On 22 October 1940, during the Blitz bombing campaign against Britain, it was decided to increase the protection of the Cabinet War Rooms by the installation of a massive layer of concrete known as 'the Slab'.[19] Up to 5 feet (1.5 metres) thick,[13] the Slab was progressively extended and by spring 1941 the increased protection had enabled the Cabinet War Rooms to expand to three times their original size.[20] While the usage of many of the War Rooms' individual rooms changed over the course of the war, the facility included dormitories for staff, private bedrooms for military officers and senior ministers, and rooms for typists or telephone switchboard operators.[21]  Two other notable rooms include the Transatlantic Telephone Room and Churchill's office-bedroom. From 1943, a SIGSALY code-scrambling encrypted telephone was installed in the basement of Selfridges, Oxford Street connected to a similar terminal in the Pentagon building.[22] This enabled Churchill to speak securely with American President Roosevelt in Washington, with the first conference taking place on 15 July 1943.[22] Later extensions were installed to both 10 Downing Street and the specially constructed Transatlantic Telephone Room within the Cabinet War Rooms.[23] Churchill's office-bedroom, open from 27 July 1940,[24] included BBC broadcasting equipment; Churchill made four wartime broadcasts from the Cabinet War Rooms, the first being on 11 September 1940.[25] Although the office room was also fitted out as a bedroom, Churchill rarely slept underground,[26] preferring to sleep at 10 Downing Street or the No.10 Annexe, a flat in the New Public Offices directly above the Cabinet War Rooms.[27] His daughter Mary Soames often slept in the bedroom allocated to Mrs Churchill.[28] Below the level of the Cabinet War Rooms, a further sub-basement nicknamed "the Dock" was provided for staff members to sleep, so that they didn't have to make their way home through heavy air raids at the end of their shifts. As the name suggests, the Dock was not a comfortable place. The ventilation system rattled throughout the night, mice were common, occupants had to stoop due to low ceilings, and there were no flushing toilets, only chemical ones. Ismay's personal secretary, Betty Green, described it as "revolting".[29] Rooms 60 Right and 60A were used as a telephone switchboard and a typing pool respectively. Due to the rudimentary nature of photocopying equipment available at the time, up to 11 typists were stationed in the typing pool at any one time, typing out copies of meeting minutes by hand.[30] Abandonment and preservationOn 15 August 1945, Japan surrendered, bringing an end to the war. The following day, the lights in the Map Room were simply turned off and the staff vacated their offices. Several were cleared and used for other purposes, but the Cabinet Room, Map Room, Transatlantic Telephone Room and Churchill's bedroom were preserved for their historic value.[31] Their maintenance became the responsibility of the Ministry of Works.[32] In March 1948 the question of public access to the War Rooms was raised in Parliament and the Minister responsible, Charles Key MP, considered that 'it would not be practicable to throw open for inspection by the general public accommodation which forms part of an office where confidential work is carried on'.[32] Even so, a tour was organised for journalists on 17 March, with members of the press being welcomed by Lord Ismay and shown around the Rooms by their custodian, Mr. George Rance.[33] While the Rooms were not open to the general public, they could be visited by appointment, with access being restricted to small groups.[34] Even so, by the 1970s (with responsibility for the Rooms having passed to the Department for the Environment in 1975)[34] tens of thousands of requests to visit the Rooms were being received every year, of which only 5,000 were successful. Meanwhile, the atmospheric conditions of the site, being dry and dusty, were having a detrimental effect on the rooms' furnishings and historic maps and other documents. The prospect was raised of decanting the contents of the Rooms to an established museum, with the National Army Museum and Imperial War Museum being suggested as candidates. In the event, £7,000 was secured to conserve the material in situ.[35] Opening and redevelopment In 1974, the Imperial War Museum was approached by the government and asked to consider taking over the administration of the site. A feasibility study was prepared but came to nothing, the museum feeling it did not have sufficient resources to commit to the War Rooms.[nb 2] In 1981, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, known as an admirer of Winston Churchill, expressed the hope that the Rooms could be opened before the next general election. The Imperial War Museum was again approached. Initially still reluctant, the museum's trustees decided in January 1982 that the museum would take over the site, on the understanding that the government would make the necessary resources available. The initial costs were to be met by the Department for the Environment and the War Rooms intended to be self-supporting thereafter.[35] The Rooms were opened to the public by Thatcher on 4 April 1984 in a ceremony attended by Churchill family members and former Cabinet War Rooms staff. At first the Rooms were administered by the museum on behalf of the Department for the Environment; in 1989 responsibility was transferred to the Imperial War Museum.[35][36] Following a major expansion in 2003, a suite of rooms used as accommodation by Churchill, his wife and close associates, was added to the museum. The restoration of these rooms, which after the war had been stripped of furnishings and used for storage, cost £7.5 million.[37] In June 2012 the museum's entrance was redesigned by Clash Architects with consulting engineers Price & Myers.[38] Intended to act as a 'beacon' for the museum,[39] the new external design included a faceted bronze entranceway, and the interior showed the cleaned and restored Portland stone walls of the Treasury building and Clive Steps. The design was described as 'appropriately martial and bulldog-like' and as 'a fusion of architecture and sculpture'.[40][41] Churchill MuseumIn 2005 the War Rooms were rebranded as the Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms, with 850 m2 (9,100 sq ft) of the site redeveloped as a biographical museum exploring Churchill's life, the development of which cost a further £6 million raised from private funds. The museum makes extensive use of audiovisual technology, with the centrepiece being a 15-metre (50 ft) interactive table that enables visitors to access digitised material, particularly from the Churchill Archives Centre.[42][nb 3] The museum is set out in chronological chunks, beginning with Churchill's appointment as Prime Minister in 1940 and going up to the end of his life in 1965 before starting again with his childhood and returning to May 1940.[43] The Churchill Museum won the 2006 Council of Europe Museum Prize.[44] During 2009–2011 the museum received over 300,000 visitors a year.[45] In May 2010 the name of the museum was shortened to Churchill War Rooms.[46] Notes

References

SourcesHolmes, Richard (2009). Churchill's Bunker: The Secret Headquarters at the Heart of Britain's Victory. London: Profile Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84668-225-4. External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Cabinet War Rooms. 51°30′07.5″N 0°07′44.5″W / 51.502083°N 0.129028°W

|

||||||||||||||||||||