|

Clitheroe

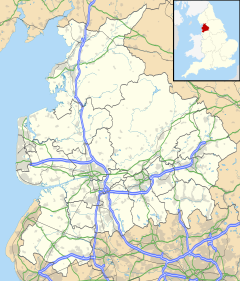

Clitheroe (/ˈklɪðəroʊ/) is a town and civil parish in the Borough of Ribble Valley, Lancashire, England; it is located 34 miles (55 km) north-west of Manchester. It is near the Forest of Bowland and is often used as a base for tourists visiting the area. In 2018, the Clitheroe built-up area had an estimated population of 16,279.[2] The town was listed in the 2017 The Sunday Times report on the best places to live in Northern England, while the wider Ribble Valley, of which Clitheroe is the most populous settlement, was listed in the 2018 and 2024 Sunday Times report on the best places to live. The town's most notable building is Clitheroe Castle, which is said to be one of the smallest Norman keeps in Great Britain. Several manufacturing companies have sites here, including Dugdale Nutrition, Hanson Cement, Johnson Matthey and Tarmac. History The name Clitheroe is thought to come from the Anglo-Saxon for "Rocky Hill",[3] and was also spelled Clyderhow and Cletherwoode,[4] amongst others. The town was the administrative centre for the lands of the Honour of Clitheroe. The Battle of Clitheroe was fought in 1138 during the Anarchy. These lands were held by Roger the Poitevin, who passed them to the de Lacy family, from whom they passed by marriage in 1310 or 1311 to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster.[4] It subsequently became part of the Duchy of Lancaster until Charles II at the Restoration bestowed it, on George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle, from whose family it descended through the house of Montague to that of Buccleuch.[4] At one point, the town of Clitheroe was given to Richard, 1st Duke of Gloucester. Up until 1835, the Lord of the Honor was also by right Lord of Bowland, the so-called Lord of the Fells.[5] The town's earliest existing charter is from 1283, granted by Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, confirming rights granted by one of his forebears between 1147 and 1177.[3] According to local legend, stepping stones across the River Ribble near the town are the abode of an evil spirit, who drowns one traveller every seven years.[6] Jet engine developmentDuring World War II, the jet engine was developed by the Rover Company.[7] Rover and Rolls-Royce met engineers from the different companies at Clitheroe's Swan & Royal Hotel. The residential area 'Whittle Close' in the town is named after Frank Whittle, being built over the site of the former jet engine test beds. Ancient monumentsThe town only has three Scheduled Ancient Monuments, Bellmanpark Lime kiln and embankment,[8] Edisford Bridge[9] and Clitheroe Castle.[10] Governance and representation The town elected two members to the Unreformed House of Commons. The Great Reform Act reduced this to one. The parliamentary borough was abolished under the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885. It was one of the boroughs reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, and remained a municipal borough, based at Clitheroe Town Hall, until the Local Government Act 1972 came into force in 1974, when it became a successor parish within the Ribble Valley district.[11] Since 1991, the town of Clitheroe has elected at least 8 out of the 10 Liberal Democrat borough councillors on Ribble Valley Borough Council, while Clitheroe Town Council has been Liberal Democrat-controlled for that period too. Likewise, since 1993, the town has elected a Liberal Democrat County Councillor to Lancashire County Council. Clitheroe was one of earliest seats to elect a Labour MP, when David Shackleton won the 1902 Clitheroe by-election for the Labour Representation Committee. He was the first Labour MP to win a by-election, and the third ever elected. He was returned unopposed, but easily won the subsequent 1906 general election, at which he was challenged by an Independent Conservative. Shackleton was General Secretary of the Textile Factory Workers Association, and at the time, there were a large number of mill workers living locally. Labour lost the seat at the 1922 election, and did not regain it until their 1945 landslide victory. The Conservatives won the seat back at the next general election, in 1950, and held it from then until 1983, when the constituency was abolished due to boundary changes. From 1885 to 1983, when the seat existed, the boundaries covered areas outside Clitheroe itself, including parts of Burnley and Colne. As part of the Ribble Valley constituency, Clitheroe has been represented by a Conservative Member of Parliament for many years, with the exception of Michael Carr, who won a by-election in 1991 for the Liberal Democrats, but who lost the seat at the general election a year later. The current MP is Jonathan Hinder, who was first elected in 2024. Climate

Economy  IndustryICI founded a chemical plant in 1941, which was sold for a reported £260 million in September 2002, to Johnson Matthey.[13] Conservatory manufacturer Ultraframe was started in Clitheroe, by John Lancaster in 1983. In March 1997, it floated on the stock exchange, being valued at £345 million in 2003. In June 2006, however, a downturn led to a takeover by Brian Kennedy's Latium Holdings.[14][15] Hanson Cement has been criticised for using industrial waste in its kilns. The company claims that its filters remove these and that government inspectors have approved the plant. Another local firm, the family-owned animal feed producer Dugdale Nutrition can trace its history back to John Dugdale who was trading at Waddington Post Office in 1850.[16] RetailHistorically, Dawsons green grocers was a significant player in the town retail fabric, circa late sixties and early seventies. Batemans Boys Wear fulfilled a retail need from approx 1968–1980. There are numerous banks and building societies, including Lloyds Bank, HSBC, and NatWest. Clitheroe has three jewellers, with Nettletons Jewellers being on the high street. In May 2007, planning permission was granted for a Homebase, although the store didn't open until April 2009.[17] In April 2015, work officially started on a new development, consisting of Aldi and Pets at Home.[18][19] In October 2015, Aldi officially opened, with Pets at Home and Vets4pets following shortly afterwards.[20] Clitheroe has five supermarkets: Booths, Tesco, Sainsbury's (including an Argos), Lidl, and Aldi. There is a shopping centre known as the Swan Courtyard. In May 2007, when Kwik Save entered administration, its store on Station Road closed. In September 2008, Booths bought the site, and expanded their store, where it currently houses charity shop YMCA.[21] Demographics

At the 2011 United Kingdom census, Clitheroe civil parish had a population of 14,765.[22] 5 electoral wards cover the same area (Salthill, Littlemoor, Edisford and Low Moor, St Mary's and Primrose). It has small Eastern European and Asian Populations which are both of similar sizes.[23] The town was listed in the 2017 The Sunday Times report on the best places to live in Northern England,[24] while the wider Ribble Valley, of which Clitheroe is the most populous settlement, was listed in the 2018 and 2024 Sunday Times report on the best places to live.[25][26] Clitheroe and the wider Ribble Valley have also been listed as healthiest and happiest place to live in the United Kingdom.[27][28][29][30][31] ReligionThere are three Anglican churches: the Parish Church of St Mary Magdalene; St James' Church; St Paul's in Low Moor. The Roman Catholic church of St Michael and St John Church is at Lowergate and St Augustine's High School in Billington is the local Roman Catholic secondary school. Trinity Methodist Church is on the edge of Castle Park in Clitheroe. There is also a United Reformed Church in the town; the Clitheroe Community Church and a Salvation Army citadel. Since 2017, there is also a Friends meeting house. A former church at Lowergate was granted permission in December 2006 to become a multi faith centre, with a Muslim prayer room. It is open for all faiths to use the rest of the building.[32] The conversion was completed in March 2014.[33] LandmarksThe castle Clitheroe Castle is argued to be the smallest Norman keep in the whole of England. It stands atop a 35-metre knoll of limestone and is one of the oldest buildings in Lancashire. The castle's most prominent feature is the hole in its side which was made in 1649 as was ordered by the government. Dixon Robinson was in residence as Steward of the Honour of Clitheroe from 1836 until his death in 1878 and resided at the castle for the same period.[34] His son Aurthur Ingram Robinson lived at the Castle after 1878, and inherited the Steward title too (see Honour of Clitheroe). TransportThe town has good local public transport links, centred around Clitheroe Interchange. Railway Clitheroe railway station is on the Ribble Valley line, providing hourly passenger services to Blackburn, Manchester Victoria and Rochdale; the route is operated by Northern Trains.[35] Services are operated usually by Class 150 diesel multiple units, & Class 156 units. Regular passenger train services had ceased in 1962; they resumed in 1994, though only south towards Blackburn at first. Ribble Valley Rail, a community rail group, is campaigning for services from Clitheroe to be extended north to Hellifield.[36] On Saturdays, DalesRail trains run to Settle and Ribblehead. A number of freight trains also pass through Clitheroe each week. BusesThere are frequent bus services from Clitheroe Interchange to the surrounding Lancashire and Yorkshire settlements. Transdev Blazefield, with its Blackburn Bus Company and Burnley Bus Company subsidiaries, is the most prominent operator; it operates mainly interurban services to other towns in Lancashire, Greater Manchester and Yorkshire. Other operators include Preston Bus, Vision Bus, Pilkington Bus, Holmeswood Coaches and Stagecoach in Lancashire. Sport  Clitheroe F.C. play in the Northern Premier League Division One North. Originally established in 1877 as Clitheroe Central, they play their home games at the Shawbridge Stadium.[37] There is also a youth football club, Clitheroe Wolves, founded in 1992.[38] Cricket has been played in Clitheroe since the 1800s, with Clitheroe Cricket Club being formed in 1862 as an amalgamation of two sides, Clitheroe Alhambra and the local Rifles Corps. Based at Chatburn Road and members of the Ribblesdale League since its inception, the club won the league title and both the Ramsbottom and Twenty-20 cups in the 2006 season.[39] The Clitheroe Golf Club was founded in 1891, and originally the course was at Horrocksford on land now quarried away. The current course was designed by James Braid, and play began in the early 1930s. It is located south of the town in the neighbouring parish of Pendleton.[40] Clitheroe Rugby Union Football Club, formed in 1977, play at the Littlemoor Ground on Littlemoor Road in the town and run two adult rugby teams.[41] In August 2005, a cycle race, the Clitheroe Grand Prix, took place in the town, with Russell Downing finishing ahead of Chris Newton.[42] In August 2006, Ben Greenwood won, with Ian Wilkinson second,[43] but in April 2007, the council decided not to support another event, citing poor attendance.[44] The town was also the start point of the second stage of the 2015 Tour of Britain.[45] Public sports facilities are available at Edisford, with the Ribblesdale Pool and Clitheroe Tennis Centre located there, along with a number of football pitches and netball courts.[46] The site is shared with the Roefield Leisure Centre, developed and operated by a registered charity whose supporters began fund-raising in 1985.[47] In April 2006, Clitheroe Skatepark officially opened in the Castle grounds, built and funded by the Lancaster Foundation charitable trust.[48] In June 2016, Clitheroe-raised mixed martial artist, Michael Bisping, won the UFC Middleweight Championship, by defeating Luke Rockhold by way of knockout in the first round of the fight.[49] On 5 July 2019 he was inducted into The UFC Hall of Fame. He is the first English fighter to be inducted. CultureIn 2018, the short documentary Alfie the Odd-Job Boy of Clitheroe featured on BBC Three. The film follows the ups and downs of 18-year-old Alfie Cookson, who set up his own business on a tandem pushbike and trailer after struggling to work for other people.[50] FestivalsClitheroe has hosted the Ribble Valley Jazz and Blues Fest since making a return in 2010 after more than 40 years. It is held annually, usually during Early May Bank Holiday weekend. The annual Clitheroe Food Festival takes place in early August. Eighty or more Lancashire food and drink producers are selected to participate by the festival organisers. Lancashire's top professional chefs, the town's retailers, groups and volunteer organisations also take part.[51] MediaLocal news and television programmes are provided by BBC North West and ITV Granada. Television signals are received from the Winter Hill TV transmitter. [52] Local radio stations are BBC Radio Lancashire on 95.5 FM, Heart North West on 105.4 FM, Smooth North West on 100.4 FM, Greatest Hits Radio Lancashire on 96.5 FM, Capital Manchester and Lancashire on 107.0 FM, and Ribble FM, a community based station which broadcast to the town and across the Ribble Valley on 106.7 FM and also online. [53] The town is served by the local newspapers, Burnley Express (formerly The Clitheroe Advertiser & Times) and Lancashire Telegraph. [54] Education The three main secondary schools in the town are Clitheroe Royal Grammar School, Ribblesdale High School and Moorland School. There are several primary schools in the town. These are St James's Church of England Primary School, St. Michael and John's Roman Catholic Primary School, Pendle Primary School, Edisford Primary School, Brookside Primary School and newly built (2024) Ribblesdale Primary School. HealthClitheroe has a health centre, accommodating the Pendleside Medical Practice and the Castle Medical Group. There is a community hospital. The area is served by the East Lancashire Commissioning Care Group. Clitheroe also has its own Ambulance, Fire and police stations. Twin townClitheroe is twinned with Rivesaltes, a small town in France. Clitheronians

Sport

Media gallery

See alsoReferences

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Clitheroe. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||