|

Cultural geography

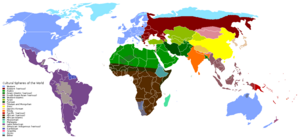

Cultural geography is a subfield within human geography. Though the first traces of the study of different nations and cultures on Earth can be dated back to ancient geographers such as Ptolemy or Strabo, cultural geography as academic study firstly emerged as an alternative to the environmental determinist theories of the early 20th century, which had believed that people and societies are controlled by the environment in which they develop.[1] Rather than studying predetermined regions based upon environmental classifications, cultural geography became interested in cultural landscapes.[1] This was led by the "father of cultural geography" Carl O. Sauer of the University of California, Berkeley. As a result, cultural geography was long dominated by American writers. Geographers drawing on this tradition see cultures and societies as developing out of their local landscapes but also shaping those landscapes.[2] This interaction between the natural landscape and humans creates the cultural landscape. This understanding is a foundation of cultural geography but has been augmented over the past forty years with more nuanced and complex concepts of culture, drawn from a wide range of disciplines including anthropology, sociology, literary theory, and feminism. No single definition of culture dominates within cultural geography. Regardless of their particular interpretation of culture, however, geographers wholeheartedly reject theories that treat culture as if it took place "on the head of a pin".[3] OverviewSome of the topics within the field of study are globalization has been theorised as an explanation for cultural convergence. This geography studies the geography of culture

History Though the first traces of the study of different nations and cultures on Earth can be dated back to ancient geographers such as Ptolemy or Strabo, cultural geography as academic study firstly emerged as an alternative to the environmental determinist theories of the early Twentieth century, which had believed that people and societies are controlled by the environment in which they develop.[1] Rather than studying predetermined regions based upon environmental classifications, cultural geography became interested in cultural landscapes.[1] This was led by Carl O. Sauer (called the father of cultural geography), at the University of California, Berkeley. As a result, cultural geography was long dominated by American writers. Sauer defined the landscape as the defining unit of geographic study. He saw that cultures and societies both developed out of their landscape, but also shaped them too.[2] This interaction between the natural landscape and humans creates the cultural landscape.[2] Sauer's work was highly qualitative and descriptive and was challenged in the 1930s by the regional geography of Richard Hartshorne. Hartshorne called for systematic analysis of the elements that varied from place to place, a project taken up by the quantitative revolution. Cultural geography was sidelined by the positivist tendencies of this effort to make geography into a hard science although writers such as David Lowenthal continued to write about the more subjective, qualitative aspects of landscape.[7] In the 1970s, new kind of critique of positivism in geography directly challenged the deterministic and abstract ideas of quantitative geography. A revitalized cultural geography manifested itself in the engagement of geographers such as Yi-Fu Tuan and Edward Relph and Anne Buttimer with humanism, phenomenology, and hermeneutics. This break initiated a strong trend in human geography toward Post-positivism that developed under the label "new cultural geography" while deriving methods of systematic social and cultural critique from critical geography.[8][9] Ongoing evolution of cultural geography  Since the 1980s, a "new cultural geography" has emerged, drawing on a diverse set of theoretical traditions, including Marxist political-economic models, feminist theory, post-colonial theory, post-structuralism and psychoanalysis. Drawing particularly from the theories of Michel Foucault and performativity in western academia, and the more diverse influences of postcolonial theory, there has been a concerted effort to deconstruct the cultural in order to reveal that power relations are fundamental to spatial processes and sense of place. Particular areas of interest are how identity politics are organized in space and the construction of subjectivity in particular places. Examples of areas of study include:

Some within the new cultural geography have turned their attention to critiquing some of its ideas, seeing its views on identity and space as static. It has followed the critiques of Foucault made by other 'poststructuralist' theorists such as Michel de Certeau and Gilles Deleuze. In this area, non-representational geography and population mobility research have dominated. Others have attempted to incorporate these and other critiques back into the new cultural geography.[10] Groups within the geography community have differing views on the role of culture and how to analyze it in the context of geography.[11] It is commonly thought that physical geography simply dictates aspects of culture such as shelter, clothing and cuisine. However, systematic development of this idea is generally discredited as environmental determinism. Geographers are now more likely to understand culture as a set of symbolic resources that help people make sense of the world around them, as well as a manifestation of the power relations between various groups and the structure through which social change is constrained and enabled.[12][13] There are many ways to look at what culture means in light of various geographical insights, but in general geographers study how cultural processes involve spatial patterns and processes while requiring the existence and maintenance of particular kinds of places. JournalsAcademic peer reviewed journals which are primarily focused on cultural geography or which contain articles that contribute to the area.

Learned societies and groups

See also

References

Further reading

|