|

Early history of American football

The early history of American football can be traced to early versions of rugby football and association football. Both games have their origin in varieties of football played in Britain in the mid–19th century, in which a football is kicked at a goal or run over a line, which in turn were based on the varieties of English public school football games. American football resulted from several major divergences from association football and rugby football, most notably the rule changes instituted by Walter Camp, a Yale University and Hopkins School graduate considered to be the "father of gridiron football". Among these important changes were the introduction of the line of scrimmage, of down-and-distance rules and of the legalization of interference.[1][2] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, gameplay developments by college coaches such as Eddie Cochems, Amos Alonzo Stagg, Parke H. Davis, Knute Rockne, John Heisman, and Glenn "Pop" Warner helped take advantage of the newly introduced forward pass. The popularity of college football grew in the United States for the first half of the 20th century. Bowl games, a college football tradition, attracted a national audience for college teams. Boosted by fierce rivalries and colorful traditions, college football still holds widespread appeal in the United States. The origin of professional football can be traced back to 1892, with Pudge Heffelfinger's $500 contract to play in a game for the Allegheny Athletic Association against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club.[3] In 1920 the American Professional Football Association was formed. This league changed its name to the National Football League (NFL) two years later, and eventually became the major league of American football. Initially a sport of Midwestern industrial towns, professional football eventually became a national phenomenon. History of American football before 1869Prehistory of American footballIn 1911, influential American football historian Parke H. Davis wrote an early history of the game of football, tracing the sport's origins to ancient times:

Forms of traditional football have been played throughout Europe and beyond since antiquity. Many of these involved handling of the ball, and scrummage-like formations. Several of the oldest examples of football-like games include the Greek game of Episkyros and the Roman game of Harpastum. Over time many countries across the world have also developed their own national football-like games. For example, New Zealand had Kī-o-rahi, Australia marn grook, Japan kemari, China cuju, Georgia lelo burti, the Scottish Borders Jeddart Ba' and Cornwall Cornish hurling, Central Italy Calcio Fiorentino, South Wales cnapan, East Anglia Campball and Ireland had caid, which an ancestor of Gaelic football.[citation needed] There is also one reference to ball games being played in southern Britain prior to the Norman Conquest. In the ninth century Nennius's Historia Britonum tells that a group of boys were playing at ball (pilae ludus).[5] The origin of this account is either southern England or Wales. References to a ball game played in northern France known as La Soule or Choule, in which the ball was propelled by hands, feet, and sticks,[6] date from the 12th century.[7] These archaic forms of football, typically classified as mob football, would be played between neighbouring towns and villages, involving an unlimited number of players on opposing teams, who would clash in a heaving mass of people struggling to drag an inflated pig's bladder by any means possible to markers at each end of a town. By some accounts, in some such events any means could be used to move the ball towards the goal, as long as it did not lead to manslaughter or murder.[8] Sometimes instead of markers, the teams would attempt to kick the bladder into the balcony of the opponents' church. A legend that these games in England evolved from a more ancient and bloody ritual of kicking the "Dane's head" is unlikely to be true. Few images of medieval football survive. One engraving from the early fourteenth century at Gloucester Cathedral, England, clearly shows two young men running vigorously towards each other with a ball in mid-air between them. There is a hint that the players may be using their hands to strike the ball. A second medieval image in the British Museum, London clearly shows a group of men with a large ball on the ground. The ball clearly has a seam where leather has been sewn together. It is unclear exactly what is happening in this set of three images, although the last image appears to show a man with a broken arm. It is likely that this image highlights the dangers of some medieval football games.[9] Most of the very early references to the game speak simply of "ball play" or "playing at ball". This reinforces the idea that the games played at the time did not necessarily involve a ball being kicked.[citation needed] The first detailed description of what was almost certainly football in England was given by William FitzStephen in about 1174–1183. He described the activities of London youths during the annual festival of Shrove Tuesday:

Numerous attempts were made to ban football games, particularly the most rowdy and disruptive forms. This was especially the case in England, and in other parts of Europe, during the Middle Ages and early modern period. Between 1324 and 1667, in England alone, football was banned by more than 30 royal and local laws. The need to repeatedly proclaim such laws demonstrated the difficulty in enforcing bans on popular games. King Edward II was so troubled by the unruliness of football in London that, on April 13, 1314, he issued a proclamation banning it:[citation needed]

In 1531, Sir Thomas Elyot wrote that:[citation needed]

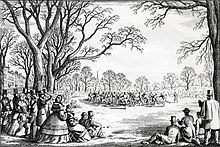

These antiquated games went into sharp decline in the 19th century when the Highway Act 1835 was passed banning the playing of football on public highways.[11] Antithetical to social change this anachronism of football continued to be played in some parts of the United Kingdom. These games still survive in a number of towns notably the Ba game played at Christmas and New Year at Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands Scotland,[12] Uppies and Downies over Easter at Workington in Cumbria and the Royal Shrovetide Football Match on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday at Ashbourne in Derbyshire, England.[13] Football in America In 1586, men from a ship commanded by an English explorer named John Davis, went ashore to play a form of football with Inuit (Eskimo) people in Greenland.[14] There are later accounts of an Inuit game played on ice, called Aqsaqtuk. Each match began with two teams facing each other in parallel lines, before attempting to kick the ball through each other team's line and then at a goal. In 1610, William Strachey, an English colonist at Jamestown, Virginia recorded a game played by Native Americans, called Pahsaheman.[15] Although there are mentions of Native Americans playing games, modern American football has its origins in the traditional football games played in the cities, villages and schools of Europe for many centuries before America was settled by Europeans. Early games appear to have had much in common with the traditional "mob football" played in England. The games remained largely unorganized until the 19th century, when intramural games of football began to be played on college campuses. Each school played its own variety of football. Princeton University students played a game called "ballown" as early as 1820.[citation needed]  A Harvard tradition known as "Bloody Monday" began in 1827, which consisted of a mass ballgame between the freshman and sophomore classes. In 1860, both the town police and the college authorities agreed the Bloody Monday had to go. The Harvard students responded by going into mourning for a mock figure called "Football Fightum", for whom they conducted funeral rites. The authorities held firm and it was a dozen years before football was once again played at Harvard. Dartmouth played its own version called "Old division football", the rules of which were first published in 1871, though the game dates to as early as the 1830s.[citation needed] All of these games, and others, shared certain commonalities. They remained largely "mob" style games, with huge numbers of players attempting to advance the ball into a goal area, often by any means necessary. Rules were simple, violence and injury were common.[16][17] The violence of these mob-style games led to widespread protests and a decision to abandon them. Yale, under pressure from the city of New Haven, banned the play of all forms of football in 1860.[16] The "Boston game" While the game was banned in colleges, it was becoming popular in numerous east coast prep schools. In the 1860s, manufactured inflatable balls were introduced through the innovations of shoemaker Richard Lindon. These were much more regular in shape than the handmade balls of earlier times, making kicking and carrying easier. Two general types of football had evolved by this time: "kicking" games (like the game played at Cambridge University) which later served as the basis for the rules of the Football Association (soccer) in 1863, and "running" (or "carrying") games, which later served as the basis for the laws laid down by the Rugby Football Union in 1871. A hybrid of the two, known as the "Boston game", was already played by a team called the Oneida Football Club. The club, considered by some historians as the first formal football club in the United States, was formed in 1862 by graduates of Boston's elite preparatory schools. They played mostly among themselves, though they organized a team of non-members to play a game in November 1863, which the Oneidas won easily. The game caught the attention of the press, and "the Boston game" continued to spread throughout the 1860s. Oneida, from 1862 to 1865, reportedly never lost a game or even gave up a single point.[16][18] The game began to return to college campuses by the late 1860s. Yale, Princeton, Rutgers University, and Brown University began playing the popular "kicking" game during this time. In 1867, Princeton used rules based on those of the London Football Association.[16] A "running game", resembling rugby football, was taken up by the Montreal Football Club in Canada in 1868.[2] Early history of intercollegiate football (1869–1932)American football historian Parke H. Davis described the period between 1869 and 1875 as the 'Pioneer Period'; the years 1876–93 he called the 'Period of the American Intercollegiate Football Association'; and the years 1894–1933 he dubbed the 'Period of Rules Committees and Conferences'.[19] Pioneer period (1869–1875)Rutgers–Princeton (1869) On November 6, 1869, Rutgers University faced Princeton University (then known as the College of New Jersey) in a game that was played with a round ball and used a set of rules suggested by Rutgers captain William J. Leggett, based on London's The Football Association's first set of rules, which were an early attempt by the former pupils of England's public schools, to unify the rules of their public schools games and create a universal and standardized set of rules for the game of football and bore little resemblance to the American game which would be developed in the following decades. By tradition more than any other criteria, it is usually regarded as the first game of intercollegiate American football.[2][3][16][20] William S. Gummere conceived the idea of an intercollegiate game between Princeton and Rutgers. He invented a set of rules and convinced William S. Leggett to join him.[21] The game was played at a Rutgers field. Two teams of 25 players attempted to score by kicking the ball over the opposing team's goal. Throwing or carrying the ball was not allowed, but there was plenty of physical contact between players. The first team to reach six goals was declared the winner. Rutgers won by a score of six to four. A rematch was played at Princeton a week later under Princeton's own set of rules (one notable difference was the awarding of a "free kick" to any player that caught the ball on the fly, which was a feature adopted from the Football Association's rules; the fair catch kick rule has survived through to modern American game). Princeton won that game by a score of 8–0. Columbia joined the series in 1870, and by 1872 several schools were fielding intercollegiate teams, including Yale and Stevens Institute of Technology.[16] Early efforts to organize the game Columbia University was the third school to field a team. The Lions traveled from New York City to New Brunswick on November 12, 1870, and were defeated by Rutgers 6 to 3. Teams fielded 20 men per side, included two goalkeepers each. The game suffered from disorganization and the players kicked and battled each other as much as the ball.[22] Later in 1870, Princeton and Rutgers played again with Princeton defeating Rutgers 6–0. This game's violence caused such an outcry that no games at all were played in 1871. Football came back in 1872, when Columbia played Yale for the first time.[23] The Yale team was coached and captained by David Schley Schaff, who had learned to play football while attending Rugby school. Schaff himself was injured and unable to the play the game, but Yale won the game 3–0 nonetheless. Later in 1872, Stevens Tech became the fifth school to field a team. Stevens lost to Columbia, but beat both New York University and City College of New York during the following year.[24] By 1873, the college students playing football had made significant efforts to standardize their fledgling game. Teams had been scaled down from 25 players to 20. The only way to score was still to bat or kick the ball through the opposing team's goal, and the game was played in two 45 minute halves on fields 140 yards long and 70 yards wide. On October 20, 1873, representatives from Yale, Princeton, and Rutgers met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City to codify the first set of intercollegiate football rules.[25] Before this meeting, which founded the first Intercollegiate Football Association, each school had its own set of rules and games were usually played using the home team's own particular code. At this meeting a list of rules, based more on The Football Association's rules than the recently founded Rugby Football Union, was drawn up for intercollegiate football games.[16] Harvard–McGill (1874) Old "Football Fightum" had been resurrected at Harvard in 1872, when Harvard resumed playing football. Harvard, however, had adopted a version of football which allowed carrying, albeit only when the player carrying the ball was being pursued. As a result of this, Harvard refused to attend the rules conference organized by the other schools and continued to play under its own code. While Harvard's voluntary absence from the meeting made it hard for them to schedule games against other American universities, it agreed to a challenge to play McGill University, from Montreal, in a two-game series. Inasmuch as rugby football had been transplanted to Canada from England, the McGill team played under a set of rules which allowed a player to pick up the ball and run with it whenever he wished. Another rule, unique to McGill, was to count tries (the act of grounding the football past the opposing team's goal line; it is important to note that there was no end zone during this time), as well as goals, in the scoring. In the Rugby rules of the time, a touchdown only provided the chance to kick a free goal from the field. If the kick was missed, the touchdown did not count.[citation needed] The McGill team traveled to Cambridge to meet Harvard. On May 14, 1874, the first game, played under Harvard's rules, was won by Harvard with a score of 3–0.[26] The next day, the two teams played under "McGill" rugby rules to a scoreless tie.[16] The games featured a round ball instead of a rugby-style oblong ball.[26] This series of games represents an important milestone in the development of the modern game of American football.[27][28] In October 1874, the Harvard team once again traveled to Montreal to play McGill in rugby, where they won by three tries. Harvard–Tufts, Harvard–Yale (1875) Harvard quickly took a liking to the rugby game, and its use of the try which, until that time, was not used in American football. The try would later evolve into the score known as the touchdown. On June 4, 1875, Harvard faced Tufts University in the first game between two American colleges played under rules similar to the McGill–Harvard contest, which was won by Tufts.[29] The rules included each side fielding 11 men, the ball was advanced by kicking or carrying it, and tackles of the ball carrier stopped play.[30]  Further elated by the excitement of McGill's version of football, Harvard challenged its closest rival, Yale, to a game which the Bulldogs accepted. The two teams agreed to play under a set of rules called the "Concessionary Rules", which involved Harvard conceding something to Yale's soccer and Yale conceding a great deal to Harvard's rugby. They decided to play with 15 players on each team. On November 13, 1875, Yale and Harvard played each other for the first time ever, where Harvard won 4–0. 2,000 spectators watched the first playing of The Game—the annual football contest between Harvard and Yale—including the future "father of American football" Walter Camp. Camp, who would enroll at Yale the next year, was torn between an admiration for Harvard's style of play and the misery of the Yale defeat, and became determined to avenge Yale's defeat. Spectators from Princeton also carried the game back home, where it quickly became the most popular version of football.[16] Period of the American Intercollegiate Football Association (1876–1893)Massasoit Convention (1876)Wikisource has original text related to this article:

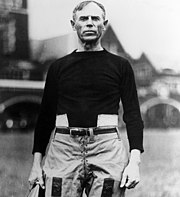

On November 23, 1876, representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia met at the Massasoit House hotel in Springfield, Massachusetts to standardize a new code of rules based on the rugby game first introduced to Harvard by McGill University in 1874. The rules were based largely on the Rugby Football Union's code from England, though one important difference was the replacement of a kicked goal with a touchdown as the primary means of scoring (a change that would later occur in rugby itself, favoring the try as the main scoring event). Three of the schools—Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton—formed the second Intercollegiate Football Association as a result of the meeting. Yale did not join the group until 1879, because of an early disagreement about the number of players per team.[1] The Intercollegiate Football Association represents the first comprehensive effort to organize and standardize American football. Walter Camp: Father of American football Walter Camp is widely considered to be the most important figure in the development of American football.[1][2][3] As a youth, he excelled in sports like track, baseball, and association football, and after enrolling at Yale in 1876, he earned varsity honors in every sport the school offered.[1] Following the introduction of rugby-style rules to American football, Camp became a fixture at the Massasoit House conventions where rules were debated and changed. Dissatisfied with what seemed to him to be a disorganized mob, he proposed his first rule change at the first meeting he attended in 1878: a reduction from fifteen players to eleven. The motion was rejected at that time but passed in 1880. The effect was to open up the game and emphasize speed over strength. Camp's most famous change, the establishment of the line of scrimmage and the snap from center to quarterback, was also passed in 1880. Originally, the snap was executed with the foot of the center. As renowned Yale center Pa Corbin described: "By standing the ball on end and exercising a certain pressure on the same, it was possible to have it bound into the quarterback's hands."[31] Later changes made it possible to snap the ball with the hands, either through the air or by a direct hand-to-hand pass.[1] Rugby league followed Camp's example, and in 1906 introduced the play-the-ball rule, which greatly resembled Camp's early scrimmage and center-snap rules. In 1966, Rugby league introduced a four-tackle rule based on Camp's early down-and-distance rules. The 1880 season also saw the first year of 11 players to a team. From 1869 to 1873, one saw 25 players to a side. From 1873 to 1875, one saw 20 players per side. 1876 to 1879 saw 15 players per side.[citation needed] Camp's new scrimmage rules revolutionized the game, though not always as intended. Princeton, in particular, used scrimmage play to slow the game, making incremental progress towards the end zone during each down. Rather than increase scoring, which had been Camp's original intent, the rule was exploited to maintain control of the ball for the entire game, resulting in slow, unexciting contests. At the 1882 rules meeting, Camp proposed that a team be required to advance the ball a minimum of five yards within three downs. These down-and-distance rules, combined with the establishment of the line of scrimmage, transformed the game from a variation of rugby football into the distinct sport of American football.[1] Camp was central to several more significant rule changes that came to define American football. In 1881, the field was reduced in size to its modern dimensions of 120 by 531⁄3 yards (109.7 by 48.8 meters). Several times in 1883, Camp tinkered with the scoring rules, finally arriving at four points for a touchdown, two points for kicks after touchdowns, two points for safeties, and five for field goals. Camp's innovations in the area of point scoring influenced rugby union's move to point scoring in 1890. In 1887, game time was set at two halves of 45 minutes each. Also in 1887, two paid officials—a referee and an umpire—were mandated for each game. A year later, the rules were changed to allow tackling below the waist, and in 1889, the officials were given whistles and stopwatches.[1] After his playing career at Yale ended in 1882, Camp was employed by the New Haven Clock Company until his death in 1925. Though no longer a player, he remained a fixture at annual rules meetings for most of his life, and he personally selected an annual All-American team every year from 1889 through 1924. The Walter Camp Football Foundation continues to select All-American teams in his honor.[32] Interference The last, and arguably most important innovation, which would at last make American football uniquely "American", was the legalization of interference, or blocking, a tactic which was highly illegal under the rugby-style rules. Interference remains strictly illegal in both rugby codes to today. The prohibition of interference in the rugby game stems from the game's strict enforcement of its offside rule, which prohibited any player on the team with possession of the ball to loiter between the ball and the goal. At first, American players would find creative ways of aiding the runner by pretending to accidentally knock into defenders trying to tackle the runner. When Walter Camp witnessed this tactic being employed during a game he refereed between Harvard and Princeton in 1879, he was at first appalled, but the next year had adopted the blocking tactics for his own team at Yale.[citation needed] During the 1880s and 1890s, teams developed increasingly complex blocking tactics including the interlocking interference technique known as the Flying wedge or "V-trick formation", which was first employed by Richard Hodge at Princeton in 1884 in a game against Penn, however, Princeton put the tactic aside for the next 4 years, only to revive it again in 1888 to combat the three-time All-American Yale guard Pudge Heffelfinger.[citation needed]  Heffelfinger soon figured out how to break up the formation by leaping high in the air with his legs tucked under him, striking the V like a human cannonball. In 1892, during a game against Yale, a Harvard fan and student Lorin F. Deland first introduced the flying wedge as a kickoff play, in which two five man squads would line up about 25 yards behind the kicker, only to converge in a perfect flying wedge running downfield, where Harvard was able to trap the ball and hand it off to the speedy All-American Charley Brewer inside the wedge.[citation needed] Despite their effectiveness, the flying wedge, "V-trick formation" and other tactics which involved interlocking interference, were outlawed in 1905 through the efforts of the rule committee led by Parke H. Davis, because of its contribution to serious injury.[33] Non-interlocking interference remains a basic element of modern American football, with many complex schemes being developed and implemented over the years, including zone blocking and pass blocking. Alex Moffat Alex Moffat was the early sport's greatest kicker and held a place in Princeton athletic history similar to Camp at Yale. American football historian David M. Nelson credits Moffat with revolutionizing the kicking game in 1883 by developing the "spiral punt", described by Nelson as "a dramatic change from the traditional end-over-end kicks".[34] He also invented the drop kick.[35] Henry "Tillie" LamarThe 1885 season was notable for one of the most celebrated football plays of the 19th century – a 90-yard punt return by Henry "Tillie" Lamar of Princeton in the closing minutes of the game against Yale. Trailing 5–0, Princeton dropped two men back to receive a Yale punt. The punt glanced off one returner's shoulder and was caught by the other, Lamar, on the dead run.[36] Lamar streaked down the left sideline, until hemmed in by two Princeton players, then cut sharply to the middle of the field, ducking under their arms and breaking loose for the touchdown. After the controversy of a darkness-shortened Yale-Princeton championship game the year before that was ruled "no contest", a record crowd turned out for the 1885 game. For the first time, the game was played on one of the campuses instead of at a neutral site, and emerged as a major social event, attracting ladies to its audience as well as students and male spectators.[37] The Lamar punt return furnished the most spectacular ending to any football game played to that point, and did much to popularize the sport of college football to the general public.[38] One source lists Princeton captain C. M. DeCamp as the player of the year.[39] Arthur Cumnock Harvard end Arthur Cumnock invented the first nose guard.[40] Cumnock's invention gained popularity, and in 1892, a newspaper article described the growing popularity of the device:

He is also credited with having been the person who developed the tradition of spring practice in football; in March 1889, Cumnock led the Harvard team in drills on Jarvis field, which is considered the first-ever spring football practice.[43] In 1913, an article in an Eastern newspaper sought to choose the greatest Harvard football player of all time. The individual chosen was Cumnock, who "the sons of John Harvard are pretty well agreed" was "the greatest Harvard player of all time."[44] As for his individual performance in the 1890 Yale game, the writer noted: "Such tackling as Cumnock did that day probably has never been equaled. He played a star offensive game, but on the defensive he was a terror. Lee McClung would come around the end with the giant Heffelfinger interfering, and the records read: 'Cumnock tackles both and brings them down.'"[44] Scoring table

Sources: [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] Note: For brief periods in the late 19th century, some penalties awarded one or more points for the opposing teams, and some teams in the late 19th and early 20th centuries chose to negotiate their own scoring system for individual games. Period of Rules Committees and Conference (1894–1932)Expansion (1894–1904) College football expanded greatly during the last two decades of the 19th century. Several major rivalries date from this time period; examples include Michigan–Notre Dame (1887), Army–Navy (1890), California–Stanford (1892), and Oklahoma–Texas (1900). November 1890 was an active time in the sport. In Baldwin City, Kansas, on the 22nd, college football was played in the state for the first time as Baker beat Kansas, 22–9.[52] On the 27th, Vanderbilt played Nashville (Peabody) at Athletic Park and won 40–0.[53] It was the first time organized football was played in the state of Tennessee.[54] The 29th saw the first instance of the above noted Army–Navy Game, a 24–0 win by Navy. EastRutgers was first to extend the reach of the game. An intercollegiate game was first played in the state of New York when Rutgers played Columbia on November 2, 1872. It was also the first scoreless tie in the history of the fledgling sport.[55] Yale football started the same year and had its first match against Columbia, the nearest college to play football. It took place at Hamilton Park in New Haven and was the first game in New England. The game used a set of rules based on association football with 20-man sides, played on a field 400 by 250 feet. Yale won 3–0, Tommy Sherman scoring the first goal and Lew Irwin the other two.[56] After the first game against Harvard, Tufts took its squad to Bates College in Lewiston, Maine for the first football game played in Maine.[57] This occurred on November 6, 1875. Penn's Athletic Association was looking to pick "a twenty" to play a game of football against Columbia. This "twenty" never played Columbia, but did play twice against Princeton.[58] Princeton won both games 6 to 0. The first of these happened on November 11, 1876, in Philadelphia and was the first intercollegiate game in the state of Pennsylvania. Brown enters the intercollegiate game in 1878.[59] The first game where one team scored over 100 points happened on October 25, 1884, when Yale routed Dartmouth 113–0. It was also the first time one team scored over 100 points and the opposing team was shut out.[60] The next week, Princeton outscored Lafayette by 140 to 0.[61] The first intercollegiate game in the state of Vermont happened on November 6, 1886, between Dartmouth and Vermont at Burlington, Vermont. Dartmouth won 91 to 0.[62] The first nighttime football game was played in Mansfield, Pennsylvania on September 28, 1892, between Mansfield State Normal and Wyoming Seminary and ended at halftime in a 0–0 tie.[63] The Army-Navy game of 1893 saw the first documented use of a football helmet by a player in a game. Joseph M. Reeves had a crude leather helmet made by a shoemaker in Annapolis and wore it in the game after being warned by his doctor that he risked death if he continued to play football after suffering an earlier kick to the head.[64] Harvard Law School student and football center William H. Lewis became the first African-American to be selected as an All-American in 1892, an honor he would receive again in 1893.[citation needed] Midwest In 1879, the University of Michigan became the first school west of Pennsylvania to establish a college football team. On May 30, 1879, Michigan beat Racine College 1–0 in a game played in Chicago. The Chicago Daily Tribune called it "the first rugby-football game to be played west of the Alleghenies."[65] Other Midwestern schools soon followed suit, including the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and the University of Minnesota. In 1881, Michigan scheduled games against the top American football teams—the Eastern powerhouses of Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Organized intercollegiate football was first played in the state of Minnesota on September 30, 1882, when Hamline was convinced to play Minnesota after a track meet. Minnesota won 2 to 0.[66] It was the first game west of the Mississippi River. The first western team to travel east was the 1881 Michigan team, which played at Harvard, Yale and Princeton.[67][68]  Organized intercollegiate football was first played in Indiana on May 13, 1884, when Butler defeated DePauw.[69] Michigan's 1894 victory over Cornell marked the first victory by a Western football school against one of the Eastern football powers. Up to that point, no Western player had been selected for the annual College Football All-America Teams selected by Eastern football authorities. Michigan lobbied for Fatty Smith as an All-American. The nation's first college football league, the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives (also known as the Western Conference), a precursor to the Big Ten Conference, was founded in 1895.[70] Led by coach Fielding H. Yost, Michigan became the first "western" national power. From 1901 to 1905, Michigan had a 56-game undefeated streak that included a 1902 trip to play in the first college football bowl game, which later became the Rose Bowl Game. During this streak, Michigan scored 2,831 points while allowing only 40.[71] Stars on the team included Willie Heston and Al Herrnstein. November 30, 1905, saw Walter Eckersall and Chicago defeat Michigan 2 to 0. Dubbed "The First Greatest Game of the Century",[72] broke Michigan's 56-game unbeaten streak and marked the end of the "Point-a-Minute" years. Eckersall was selected as the quarterback for Walter Camp's "All-Time All-America Team" honoring the greatest college football players during the sport's formative years.[73] After his playing days, Eckersall remained a prominent figure in football. He had a successful dual career as a sportswriter for the Chicago Tribune, and as a referee. As an official, Eckersall was considered one of the best and officiated at many high-profile games. SouthSouth AtlanticOrganized intercollegiate football was first played in the state of Virginia and the south on November 2, 1873, in Lexington between Washington and Lee and VMI. Washington and Lee won 4–2.[74] Some industrious students of the two schools organized a game for October 23, 1869 – but it was rained out.[75] Students of the University of Virginia were playing pickup games of the kicking-style of football as early as 1870, and some accounts even claim it organized a game against Washington and Lee College in 1871; but no record has been found of the score of this contest. Due to scantness of records of the prior matches some will claim Virginia v. Pantops Academy November 13, 1887, as the first game in Virginia.  On April 9, 1880, at Stoll Field, Transylvania University (then called Kentucky University) beat Centre College by the score of 13+3⁄4–0 in what is often considered the first recorded game played in the South.[76] The first game of "scientific football" in the South was the first instance of the Victory Bell rivalry between North Carolina and Duke (then known as Trinity College) held on Thanksgiving Day, 1888, at the North Carolina State Fairgrounds in Raleigh, North Carolina.[77] On November 30, 1882, cadet Vaulx Carter organized a game between the Naval Academy and the Clifton Athletic Club (in fact Johns Hopkins University) and won 8–0, the first intercollegiate game in Maryland. It snowed heavily before the game, to the point where players for both teams had to clear layers of snow off of the field, making large piles of snow along the sides of the playing ground. Both teams also nailed strips of leather to the bottom of their shoes to help deal with slipping.[78] The field was 110 yards by 53 yards, with goalposts 25 feet (7.6 m) apart and 20 feet (6.1 m) high. During play, the ball was kicked over the seawall a number of times, once going so far out it had to be retrieved by boat before play could continue.[79] The following season, Gallaudet college and Georgetown played twice; the first intercollegiate games in Washington, D. C. The deaf-mute Gallaudet players sewed their own uniforms, made of heavy canvas with black and white stripes.[80][81] On November 13, 1887, the Virginia Cavaliers and Pantops Academy fought to a scoreless tie in the first organized football game in the state of Virginia.[82] Students at UVA were playing pickup games of the kicking-style of football as early as 1870, and some accounts even claim that some industrious ones organized a game against Washington and Lee College in 1871, just two years after Rutgers and Princeton's historic first game in 1869. But no record has been found of the score of this contest. Washington and Lee also claims a 4 to 2 win over VMI in 1873.[74] The 1889 Virginia Cavaliers are the first to claim a mythical southern championship.[83] On October 18, 1888, the Wake Forest Demon Deacons defeated the North Carolina Tar Heels 6 to 4 in the first intercollegiate game in the state of North Carolina.[84] The first "scientific game" in the state occurred on Thanksgiving of the same year when North Carolina played Duke (then Trinity). Duke won 16 to 0.[85] Princeton star Hector Cowan traveled south and trained the Tar Heels.[86] The 116–0 drubbing of Virginia by Princeton in 1890 signaled football's arrival in the south.[87][88] On September 27, 1902, Georgetown beat Navy 4 to 0. It is claimed by Georgetown authorities as the game with the first ever "roving center" or linebacker when Percy Given stood up, in contrast to the usual tale of Germany Schulz.[89] The first linebacker in the South is often considered to be Sewanee's Frank Juhan. Deep South On December 14, 1889, Wofford defeated Furman 5 to 1 in the first intercollegiate game in the state of South Carolina. The game featured no uniforms, no positions, and the rules were formulated before the game.[90] 1896 saw the first instance of the "Big Thursday" Clemson–South Carolina rivalry in Columbia, another seminal moment in football below the South Atlantic States.[91] January 30, 1892, saw the first football game played in the state of Georgia when the Georgia Bulldogs defeated Mercer 50–0 at Herty Field. The 1892 Vanderbilt Commodores were the first team in the memory of Grantland Rice. Rice recalled Phil Connell then would be a good player in any era.[92] The beginnings of the contemporary Southeastern Conference and Atlantic Coast Conference start with the founding of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association. The SIAA was founded on December 21, 1894, by Dr. William Dudley, a chemistry professor at Vanderbilt.[93] The original members were Alabama, Auburn, Georgia, Georgia Tech, North Carolina, Sewanee, and Vanderbilt. Clemson, Cumberland, Kentucky, LSU, Mercer, Mississippi, Mississippi A&M (Mississippi State), Southwestern Presbyterian University, Tennessee, Texas, Tulane, and the University of Nashville joined the following year in 1895 as invited charter members.[94] The conference was originally formed for "the development and purification of college athletics throughout the South".[95]  It is thought that the first forward pass in football occurred in the SIAA's first season of play, on October 26, 1895, in a game between Georgia and North Carolina when, out of desperation, the ball was thrown by the North Carolina back Joel Whitaker instead of punted and George Stephens caught the ball.[96] On November 9, 1895 John Heisman executed a hidden ball trick utilizing quarterback Reynolds Tichenor to get Auburn's only touchdown in a 6 to 9 loss to Vanderbilt. During the play the ball was snapped to a half-back who was able to slip it under the back of the quarterback's jersey and who in turn was able to trot in for the touchdown. This was also the first game in the south decided by a field goal.[97] Heisman later used the trick against Pop Warner's Georgia team. Warner picked up the trick and later used it at Cornell against Penn State in 1897.[98] He then used it in 1903 at Carlisle against Harvard and garnered national attention. The 1897 Vanderbilt Commodores won the team's first conference title. The mythical title "champion of the south" had to be disputed with Virginia after a scoreless tie. The next season, the Cavaliers defeated Vanderbilt at Louisville 18–0 in the South's most anticipated game of the season.[99] The Cavaliers ended the season with a loss to North Carolina, which finished what is to-date its only undefeated season. The 1899 Sewanee Tigers are one of the all-time great teams of the early sport. The team went 12–0, outscoring opponents 322 to 10. Known as the "Iron Men", with just 18 men they had a six-day road trip with five shutout wins over Texas A&M; Texas; Tulane; LSU; and Ole Miss. It is recalled memorably with the phrase "and on the seventh day they rested".[100][101] Grantland Rice called them "the most durable football team I ever saw."[102] The only close game was an 11–10 win over John Heisman's Auburn Tigers. Auburn ran an early version of the hurry-up offense.[103] A documentary on this team was released in 2022 called, Unrivaled: Sewanee 1899. Unrivaled: Sewanee 1899 Organized intercollegiate football was first played in the state of Florida in 1901.[104] A 7-game series between intramural teams from Stetson and Forbes occurred in 1894. The first intercollegiate game between official varsity teams was played on November 22, 1901. Stetson beat Florida Agricultural College at Lake City, one of the four forerunners of the University of Florida, 6–0, in a game played as part of the Jacksonville Fair.[105]  On Thanksgiving Day 1903 a game was scheduled in Montgomery, Alabama between the best teams from each region of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association for an "SIAA championship game", pitting Cumberland against Heisman's Clemson. The game ended in an 11–11 tie causing many teams to claim the title. Heisman pressed hardest for Cumberland to get the claim of champion. It was his last game as Clemson head coach.[106] 1904 saw big coaching hires in the south: Mike Donahue at Auburn, John Heisman at Georgia Tech, and Dan McGugin at Vanderbilt were all hired that year. Both Donahue and McGugin just came from the north that year, Donahue from Yale and McGugin from Michigan, and were among the initial inductees of the College Football Hall of Fame. The undefeated 1904 Vanderbilt team scored an average of 52.7 points per game, the most in college football that season, and allowed just four points. One publication claims "The first scouting done in the South was in 1905, when Dan McGugin and Captain Innis Brown, of Vanderbilt went to Atlanta to see Sewanee play Georgia Tech."[107] SouthwestThe first college football game in Oklahoma Territory occurred on November 7, 1895, when the 'Oklahoma City Terrors' defeated the Oklahoma Sooners 34 to 0. The Terrors were a mix of Methodist college students and high schoolers.[108] The Sooners did not manage a single first down. By next season, Oklahoma coach John A. Harts had left to prospect for gold in the Arctic.[109][110] Organized football was first played in the territory on November 29, 1894, between the Oklahoma City Terrors and Oklahoma City High School. The high school won 24 to 0.[109] Pacific Coast In 1891, the first Stanford football team was hastily organized and played a four-game season beginning in January 1892 with no official head coach. Following the season, Stanford captain John Whittemore wrote to Yale coach Walter Camp asking him to recommend a coach for Stanford. To Whittemore's surprise, Camp agreed to coach the team himself, on the condition that he finish the season at Yale first.[111] As a result of Camp's late arrival, Stanford played just three official games, against San Francisco's Olympic Club and rival California. The team also played exhibition games against two Los Angeles area teams that Stanford does not include in official results.[112][113] Camp returned to the East Coast following the season, then returned to coach Stanford in 1894 and 1895. Herbert Hoover was Stanford's student financial manager.[114] On December 25, 1894, Amos Alonzo Stagg's Chicago Maroons agreed to play Camp's Stanford football team in San Francisco in the first postseason intersectional contest, foreshadowing the modern bowl game.[115][116] Future president Herbert Hoover was Stanford's student financial manager.[114] Chicago won 24 to 4.[117] Stanford won a rematch in Los Angeles on December 29 by 12 to 0.[118] USC first fielded an American football team in 1888. Playing its first game on November 14 of that year against the Alliance Athletic Club, in which USC gained a 16–0 victory. Frank Suffel and Henry H. Goddard were playing coaches for the first team which was put together by quarterback Arthur Carroll; who in turn volunteered to make the pants for the team and later became a tailor.[119] USC faced its first collegiate opponent the following year in fall 1889, playing St. Vincent's College to a 40–0 victory.[119] In 1893, USC joined the Intercollegiate Football Association of Southern California (the forerunner of the SCIAC), which was composed of USC, Occidental College, Throop Polytechnic Institute (Cal Tech), and Chaffey College. Pomona College was invited to enter, but declined to do so. An invitation was also extended to Los Angeles High School.[120]  The Big Game between Stanford and California is the oldest college football rivalry in the West. The first game was played on San Francisco's Haight Street Grounds on March 19, 1892, with Stanford winning 14–10. The term "Big Game" was first used in 1900, when it was played on Thanksgiving Day in San Francisco. During that game, a large group of men and boys, who were observing from the roof of the nearby S.F. and Pacific Glass Works, fell into the fiery interior of the building when the roof collapsed, resulting in 13 dead and 78 injured.[121][122][123][124][125] On December 4, 1900, the last victim of the disaster (Fred Lilly) died, bringing the death toll to 22; and, to this day, the "Thanksgiving Day Disaster" remains the deadliest accident to kill spectators at a U.S. sporting event.[126] The University of Oregon began playing American football in 1894 and played its first game on March 24, 1894, defeating Albany College 44–3 under head coach Cal Young.[127][128][129] Cal Young left after that first game and J.A. Church took over the coaching position in the fall for the rest of the season. Oregon finished the season with two additional losses and a tie, but went undefeated the following season, winning all four of its games under head coach Percy Benson.[129][130][131] In 1899, the Oregon football team left the state for the first time, playing the California Golden Bears in Berkeley, California.[127] American football at Oregon State University started in 1893 shortly after athletics were initially authorized at the college. Athletics were banned at the school in May 1892, but when the strict school president, Benjamin Arnold, died, President John Bloss reversed the ban.[132] Bloss's son William started the first team, on which he served as both coach and quarterback.[133] The team's first game was an easy 63–0 defeat over the home team, Albany College. In May 1900, Fielding H. Yost was hired as the football coach at Stanford University,[134] and, after traveling home to West Virginia, he arrived in Palo Alto, California, on August 21, 1900.[135] Yost led the 1900 Stanford team to a 7–2–1, outscoring opponents 154 to 20. The next year in 1901, Yost was hired by Charles A. Baird as the head football coach for the Michigan Wolverines football team. On January 1, 1902, Yost's dominating 1901 Michigan Wolverines football team agreed to play a 3–1–2 team from Stanford University in the inaugural Tournament East-West football game what is now known as the Rose Bowl Game by a score of 49–0 after Stanford captain Ralph Fisher requested to quit with eight minutes remaining. The 1905 season marked the first meeting between Stanford and USC. Consequently, Stanford is USC's oldest existing rival.[136] The Big Game between Stanford and Cal on November 11, 1905, was the first played at Stanford Field, with Stanford winning 12–5.[111] Missouri ValleyThe 1905 Washburn vs. Fairmount football game marked the first experiment with the forward pass and with the ten-yard requirement for first downs.[citation needed] Mountain West   The University of Colorado Boulder began playing American football in 1890. Colorado found much success in its early years, winning eight Colorado Football Association Championships (1894–97, 1901–08).[citation needed] The following was taken from the Silver & Gold newspaper of December 16, 1898. It was a recollection of the birth of Colorado football written by one of CU's original gridders, John C. Nixon, also the school's second captain. It appears here in its original form:

In 1909, the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference was founded, featuring four members, Colorado, Colorado College, Colorado School of Mines, and Colorado Agricultural College. The University of Denver and the University of Utah joined the RMAC in 1910. For its first thirty years, the RMAC was considered a major conference equivalent to today's Division I, before 7 larger members left and formed the Mountain States Conference (also called the Skyline Conference).[citation needed] Violence and controversy (1905)

A Scottish author wrote in 1908 that[139]

From its earliest days as a mob game, football was a violent sport.[16] The 1894 Harvard–Yale game, known as the "Hampden Park Blood Bath", resulted in crippling injuries for four players; the contest was suspended until 1897. The annual Army–Navy game was suspended from 1894 to 1898 for similar reasons.[140] One of the major problems was the popularity of mass-formations like the flying wedge, in which a large number of offensive players charged as a unit against a similarly arranged defense. The resultant collisions often led to serious injuries and sometimes even death.[141] Georgia fullback Richard Von Albade Gammon notably died on the field from concussions received against Virginia in 1897, causing Georgia, Georgia Tech, and Mercer to temporarily stop their football programs. In 1905 there were 19 fatalities nationwide. President Theodore Roosevelt reportedly threatened to shut down the game if drastic changes were not made.[142] However, the threat by Roosevelt to eliminate football is disputed by sports historians. What is absolutely certain is that on October 9, 1905, Roosevelt held a meeting of football representatives from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Though he lectured on eliminating and reducing injuries, he never threatened to ban football. He also lacked the authority to abolish football and was, in fact, actually a fan of the sport and wanted to preserve it. The President's sons were also playing football at the college and secondary levels at the time.[143] Meanwhile, John H. Outland held an experimental game in Wichita, Kansas that reduced the number of scrimmage plays to earn a first down from four to three in an attempt to reduce injuries.[144] The Los Angeles Times reported an increase in punts and considered the game much safer than regular play but that the new rule was not "conducive to the sport".[145] Finally, on December 28, 1905, 62 schools met in New York City to discuss rule changes to make the game safer. As a result of this meeting, the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, later named the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), was formed.[146] One rule change introduced in 1906, devised to open up the game and reduce injury, was the introduction of the legal forward pass. Though it was underutilized for years, this proved to be one of the most important rule changes in the establishment of the modern game.[147] Move towards modernization and innovation (1906–1932) As a result of the 1905–1906 reforms, mass formation plays became illegal and forward passes legal. Bradbury Robinson, playing for visionary coach Eddie Cochems at St. Louis University, threw the first legal pass in a September 5, 1906, game against Carroll College at Waukesha. Other important changes, formally adopted in 1910, were the requirements that at least seven offensive players be on the line of scrimmage at the time of the snap, that there be no pushing or pulling, and that interlocking interference (arms linked or hands on belts and uniforms) was not allowed. These changes greatly reduced the potential for collision injuries.[148] Several coaches emerged who took advantage of these sweeping changes. Amos Alonzo Stagg introduced such innovations as the huddle, the tackling dummy, and the pre-snap shift.[149] Other coaches, such as Pop Warner and Knute Rockne, introduced new strategies that still remain part of the game. Besides these coaching innovations, several rules changes during the first third of the 20th century had a profound impact on the game, mostly in opening up the passing game. In 1914, the first roughing-the-passer penalty was implemented. In 1918, the rules on eligible receivers were loosened to allow eligible players to catch the ball anywhere on the field—previously strict rules were in place only allowing passes to certain areas of the field.[150] Scoring rules also changed during this time: field goals were lowered to three points in 1909[3] and touchdowns raised to six points in 1912.[151] Star players that emerged in the early 20th century include Jim Thorpe, Red Grange, and Bronko Nagurski; these three made the transition to the fledgling NFL and helped turn it into a successful league. Sportswriter Grantland Rice helped popularize the sport with his poetic descriptions of games and colorful nicknames for the game's biggest players, including Notre Dame's "Four Horsemen" backfield and Fordham University's linemen, known as the "Seven Blocks of Granite".[152]  Thorpe gained nationwide attention for the first time in 1911.[153] He scored all his team's points—four field goals and a touchdown—in an 18–15 upset of Harvard. The 1912 season included many rule changes such as the 100-yard field and the 6-point touchdown. The first six-point touchdowns were registered in Carlisle's 50–7 win over Albright College on September 21.[154] At season's end, Jim Thorpe had rushed for some 2,000 yards.[155][156] Thorpe also competed in track and field, baseball, lacrosse and even ballroom dancing, winning the 1912 intercollegiate ballroom dancing championship.[157] In the spring of 1912, he started training for the Olympics. When Army scheduled Notre Dame as a warm-up game in 1913, they thought little of the small school. The end Knute Rockne and quarterback Gus Dorais made innovative use of the forward pass, still at that point a relatively unused weapon, to defeat Army 35–13 and helped establish the school as a national power. By 1915, Minnesota developed the first great passing combination of Pudge Wyman to Bert Baston.[158] EastThe "Big Three" continued their dominance in the early era of the forward pass. Yale's Ted Coy was selected as fullback on Camp's All-Time All-America team. "He ran through the line with hammering, high knee action then unleashed a fast, fluid running motion through the secondary."[159] The Minnesota shift gained national attention when it was adopted by Yale in 1910.[160] Henry L. Williams, an 1891 graduate of Yale, had earlier repeatedly offered to mentor his alma mater in the formation, but was rebuffed because the Elis would "not [take] football lessons from a Western university."[161] In 1910, the Elis suffered early season setbacks at the hands of inferior opponents, and sought an advantage to use in its game against strong Princeton and Harvard squads.[160] Former Yale end Thomas L. Shevlin, who had served as an assistant coach at Minnesota,[162] taught the team the shift. Yale used the Minnesota shift against both opponents, and beat Princeton, 5–3, and tied Harvard, 0–0.[160]  Fritz Pollard attended Brown University, where he majored in chemistry and played half-back on the Brown football team. In 1916 he led Brown to the second Rose Bowl in 1916, in which he was the first black player to play in the Rose Bowl.[163] He became the first black back to be named to Walter Camp's All-America team in 1916, with Camp ranking Pollard as "one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen". For his exploits at Brown, Pollard was elected to the National College Football Hall of Fame in 1954 — the first black person ever chosen.[164] The game between West Virginia and Pittsburgh on October 8, 1921, saw the first live radio broadcast of a college football game when Harold W. Arlin announced that year's Backyard Brawl played at Forbes Field on KDKA. Pitt won 21–13.[165] Bill Roper had installed a passing attack at Princeton.[166] On October 28, 1922, Princeton and Chicago played the first game to be nationally broadcast on radio. Princeton won 21–18 in a hotly contested game which had Princeton dubbed the "Team of Destiny" by Grantland Rice.[167] In 1925, Dartmouth beat Cornell 62–13 on its way to a national title. Swede Oberlander threw for 6 touchdowns and accounted for 477 yards of total offense. Cornell coach Gil Dobie retorted "We won 13–0. Passing is not football."[158] MidwestIn 1907 at Champaign, Illinois Chicago and Illinois played in the first game to have a halftime show featuring a marching band.[168] Chicago won 42–6. Notre Dame and IowaKnute Rockne took over from his predecessor Jesse Harper in the war-torn season of 1918 with a team including George Gipp and Curly Lambeau. With Gipp, Rockne had an ideal handler of the forward pass,[166][169] and a receiver in Bernard Kirk. The 1919 team went undefeated and were a national champion. Gipp died December 14, 1920 1920, just two weeks after being elected Notre Dame's first All-American by Walter Camp. Gipp likely contracted strep throat and pneumonia while giving punting lessons after his final game, November 20 against Northwestern University. Since antibiotics were not available in the 1920s, treatment options for such infections were limited and they could be fatal even to young, healthy individuals.  John Mohardt led the 1921 Notre Dame team to a 10–1 record, suffering its only loss to Howard Jones coached and Aubrey Devine-led Iowa. Grantland Rice wrote that "Mohardt could throw the ball to within a foot or two of any given space" and noted that the 1921 Notre Dame team "was the first team we know of to build its attack around a forward passing game, rather than use a forward passing game as a mere aid to the running game".[170] Mohardt had both Eddie Anderson and Roger Kiley at end to receive his passes. The loss to Iowa snapped a 20-game winning streak for Rockne and Notre Dame, which would be the longest winning streak of Rockne's career. One of the criticisms fans had of the previous Iowa coach, Hawley, was that he could not convince talented Iowa players to play at Iowa. Jones succeeded in that respect; the 1921 Hawkeyes started 11 native Iowans. Despite the graduations of many key players, Iowa again posted a perfect 7–0 final record in 1922. Iowa again went 5–0 in the Big Ten, capturing its second straight Big Ten crown. It is the only time in Iowa history that the Hawkeyes have won consecutive conference titles.[citation needed] The 1924 Irish featured the "Four Horsemen": Harry Stuhldreher, Don Miller, Jim Crowley, and Elmer Layden. The Irish capped an undefeated, 10–0 season with a victory over Stanford in the Rose Bowl. Stanford's Ernie Nevers played all 60 minutes in the game and rushed for 114 yards, more yardage than all the Four Horsemen combined.[citation needed] In 1927, Rockne's complex shifts led directly to a rule change whereby all offensive players had to stop for a full second before the ball could be snapped. On November 10, 1928, when the "Fighting Irish" team was losing to Army 6–0 at the end of the half, Rockne entered the locker room and told the team the words he heard on Gipp's deathbed in 1920: "I've got to go, Rock. It's all right. I'm not afraid. Some time, Rock, when the team is up against it, when things are going wrong and the breaks are beating the boys, tell them to go in there with all they've got and win just one for the Gipper. I don't know where I'll be then, Rock. But I'll know about it, and I'll be happy."[171] This inspired the team, which then outscored Army in the second half and won the game 12–6. The phrase "Win one for the Gipper" was later used as a political slogan by Ronald Reagan, who in 1940 portrayed Gipp in Knute Rockne, All American. The 1929 and 1930 Notre Dame teams were also declared national champions.[citation needed] Michigan and IllinoisBernard Kirk transferred to Michigan in 1920, and died in a car wreck after being selected All-American in 1922. Michigan won a national title in 1923, led by the likes of Harry Kipke and Jack Blott. In 1925, Benny Friedman to Bennie Oosterbaan proved one of the sport's great pass-receiver combinations. Yost proclaimed the 1925 team his greatest.[158]  Also in 1923, Red Grange burst on the scene at Illinois. Grange then vaulted to national prominence as a result of his performance in the October 18, 1924, game against Michigan. This was the grand opening game for the new Memorial Stadium, built as a memorial to University of Illinois students and alumni who had served in World War I. The Michigan Wolverines were going for the national championship. He returned the opening kickoff for a 95-yard touchdown and scored three more touchdowns on runs of 67, 56, and 44 yards in the first 12 minutes–the last three in less than seven minutes.[172] On his next carry, he ran 56 yards for yet another touchdown. Before the game was over, Grange ran back another kickoff for yet another touchdown. He scored six touchdowns in all. Illinois won the game by a lopsided score of 39 to 14. The game inspired Grantland Rice to write this poetic description: