|

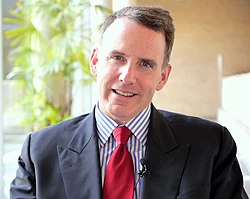

Edward Glaeser

Edward Ludwig Glaeser (born May 1, 1967) is an American economist who is currently the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics at Harvard University, where he is also the Chairman of the Department of Economics.[1] He directs the Cities Research Programme at the International Growth Centre.[2] Born in New York City, Glaeser was educated at the Collegiate School and Princeton University, where he received his AB in economics in 1988.[3] After receiving a PhD in economics from the University of Chicago in 1992, he joined the faculty of Harvard University. He has served as the director of the Taubman Center for State and Local Government, and as the director of the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston (both at Harvard Kennedy School).[4] He is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and a contributing editor at City Journal.[5] He also chairs the Advisory Council of the Liveable London unit at Policy Exchange.[6] Glaeser and John A. List were mentioned as reasons for which the American Economic Association began to award the John Bates Clark Medal annually in 2009.[7] Glaeser has been a faculty research fellow at the NBER since 1993, and was an editor of the Quarterly Journal of Economics from 1998 to 2008.[3] He was elected a Fellow of the Econometric Society in 2005, and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2010.[3][8][9] According to a review in The New York Times,[10] his book Triumph of the City[11] summarises years of research into the role that cities play in fostering human achievement and "is at once polymathic and vibrant."[10] Glaeser is known for his work showing the economic and social benefits of dense and abundant housing in cities.[12] Family background and influenceGlaeser was born in Manhattan, New York to Ludwig Glaeser (1930-September 27, 2006) and Elizabeth Glaeser.[13] His father was born in Berlin in 1930, lived in Berlin during World War II and moved to West Berlin in the 1950s. Ludwig Glaeser received a degree in architecture from the Darmstadt University of Technology, and a PhD in art history from the Free University of Berlin, before joining the staff of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1963. He would go on to become Curator of the Department of Architecture and Design in 1969.[14] Of his father, Glaeser said "his passion for cities and buildings nurtured my own". Glaeser described how his father supported new construction and change if it met aesthetic standards. According to Glaeser, his father "disliked dreary postwar apartment buildings and detested ugly suburban communities"; Glaeser himself thought that while “much postwar construction may be dull”, the buildings allowed “millions of Americans to live in the way that they desired”.[15] Glaeser's work also argues against local anti-density zoning laws and federal government policies that encourage sprawl, such as the mortgage tax deduction and federal highway programs.[10] Glaeser's career was also influenced by his mother, Elizabeth Glaeser, who was Head of Capital Markets at Mobil for 20 years, before joining Deloitte & Touche as Director of Corporate Risk Practice. She earned an MBA degree when Edward was ten years old and occasionally brought him to her classes. He remembers her teaching him microeconomic concepts, such as marginal cost price theory.[16] Glaeser admires many aspects of the work of Jane Jacobs; they both argue that "cities are good for the environment."[17] He disagrees with her on densification through height. He advocates for higher buildings in cities while Jacobs deplored the 1950s and 1960s public housing projects inspired by Le Corbusier. The austere, dehumanizing New York high rises eventually became the "projects" straying far from their original intent. She believed in preserving West Greenwich Village's smaller historical buildings for personal, economic and aesthetic reasons. Glaeser grew up in a high rise and believes that higher buildings provide more affordable housing. He calls for elimination or lessening of height limitation restrictions, preservationist statutes and other zoning laws.[17] WritingsGlaeser has published almost five articles per year since 1992 in leading peer-reviewed academic economics journals, in addition to many books, other articles, blogs, and op-eds.[18] Glaeser has made substantial contributions to the empirical study of urban economics. In particular, his work examining the historical evolution of economic hubs like Boston and New York City has had major influence on both economics and urban geography. Glaeser also has written on a variety of other topics, ranging from social economics to the economics of religion, from both contemporary and historical perspectives. His work has earned the admiration of a number of prominent economists. George Akerlof, the 2001 Nobel laureate in economics praised Glaeser as a "genius", and Gary Becker, the 1992 Nobel laureate in economics, commented that before Glaeser, "urban economics was dried up. No one had come up with some new ways to look at cities."[16] Despite the seeming disparateness of the topics he has examined, most of Glaeser's work can be said to apply economic theory (especially price theory and game theory) to questions of human economic and social behavior. Glaeser develops models using these tools and then evaluates them with real-world data, so as to verify their applicability. A number of his papers in applied economics are co-written with his Harvard colleague, Andrei Shleifer. In 2006, Glaeser began writing a regular column for the New York Sun. He writes a monthly column for The Boston Globe. He blogs frequently for The New York Times at Economix, and he has written essays for The New Republic. Although his most recent book, Triumph of the City (2011),[11] celebrates the city, he moved with his wife and children to the suburbs around 2006 because of "home interest deduction, highway infrastructure and local school systems".[19] He explained that this move is further "evidence of how public policy stacks the deck against cities. [B]ecause of all the good that comes out of city life—both personal and municipal—people should take a hard look at the policies that are driving residents into the suburbs.[19] Contribution to urban economics and political economyGlaeser has published in leading economic journals on many topics in the field of urban economics. In early work, he found that over decades, industrial diversity contributes more to economic growth than specialization, which contrasts with work by other urban economists like Vernon Henderson of Brown University. He has published influential studies on inequality. His work with David Cutler of Harvard identified harmful effects of segregation on black youth in terms of wages, joblessness, education attainment, and likelihood of teen pregnancy. They found that the effect of segregation was so harmful to blacks that if black youth lived in perfectly integrated metropolitan areas, their success would be no different from white youth on three of four measures and only slightly different on the fourth.[20] In 2000 Glaeser, Kahn and Rappaport challenged the 1960s urban land use theory that claimed the poor live disproportionately in cities because richer consumers who wanted more land chose to live in the suburbs where available land was less expensive. They found that the reasons for the higher rate of poverty in cities (17% in 1990) compared to suburbs (7.4%) in the United States were the accessibility of public transportation and pro-poor central cities' policies which encouraged more poor people to choose to move to and live in central cities.[21] He reiterated this in an interview in 2011, "The fact that there is urban poverty is not something cities should be ashamed of. Because cities don't make people poor. Cities attract poor people. They attract poor people because they deliver things that people need most of all—economic opportunity."[19] Glaeser and Harvard economist Alberto Alesina compared public policies to reduce inequality and poverty in the United States with Europe (Alesina and Glaeser 2004). Differing attitudes towards those less fortunate partially explain differences in the redistribution of income from rich to poor. Sixty percent of Europeans and 29% of Americans believe that the poor are trapped in poverty. Only 30% of Americans believe that luck determines income compared with 60% of Europeans. Sixty percent of Americans believe the poor are lazy while only 24% of Europeans believe this to be true. But they conclude that racial diversity in the United States, with the dominant group being white and the poor mainly non-white, led to resistance to reduce inequality in the United States through redistribution. Surprisingly the United States political structures are centuries old and remain much more conservative than their European counterparts as the latter have undergone much political change.[22][23] He has also made important contributions in the field of social capital by identifying underlying economic incentives for social association and volunteering. For example, he and colleague Denise DiPasquale found that homeowners are more engaged citizens than renters.[24] In experimental work, he found that students reporting being more trusting also act in more trustworthy ways. In recent years, Glaeser has argued that human capital explains much of the variation in urban and metropolitan level prosperity."[25] He has extended the argument to the international level, arguing that the high levels of human capital, embodied by European settlers in the New World and elsewhere, explains the development of freer institutions and economic growth in those countries over centuries.[26] In other work, he finds that human capital is associated with reductions in corruption and other improvements in government performance.[27] During the 2000s, Glaeser's empirical research has offered a distinctive explanation for the increase in housing prices in many parts of the United States over the past several decades. Unlike many pundits and commentators, who attribute skyrocketing housing prices to a housing bubble created by Alan Greenspan's monetary policies, Glaeser pointed out that the increase in housing prices was not uniform throughout the country (Glaeser and Gyourko 2002).[28] Glaeser and Gyourko (2002) argued that while the price of housing was significantly higher than construction costs in Boston, Massachusetts and San Francisco and California, in most of the United States, the price of housing remained "close to the marginal, physical costs of new construction." They argued that dramatic differences in price of housing versus construction costs occurred in places where permits for new buildings[29] had become difficult to obtain (since the 1970s). Compounded with strict zoning laws the supply of new housing in these cities was seriously disrupted. Real estate markets were thus unable to accommodate increases in demand, and housing prices skyrocketed. Glaeser also points to the experience of states such as Arizona and Texas, which experienced tremendous growth in demand for real estate during the same period but, because of looser regulations and the comparative ease of obtaining new building permits, did not witness abnormal increases in housing prices.[28] Glaeser and Gyourko (2008) observed that in spite of the mortgage meltdown and the ensuing drop in housing prices, Americans continue to face housing affordability challenges. Housing policy makers, however, need to recognize that housing affordability differs from region to region and affects classes differently. Public policies should reflect those differences. The middle class confront affordability issues that could be resolved by allowing for more new home constructions by removing zoning restrictions at the municipal level. Glaeser and Gyourko (2008) recommend direct income transfers for low income families to resolve their specific housing needs rather than government interference in the housing market itself.[30] Glaeser (2011) claimed that public policy in Houston, Texas, the only city in the United States with no zoning code and therefore, a very elastic housing supply, enabled construction to respond to the demand of a plentiful number of new affordable houses even in 2006. He argued that this kept Houston prices flat while elsewhere they escalated.[11] Contribution to health economicsIn 2003, Glaeser collaborated with David Cutler and Jesse Shapiro on a research paper that attempted to explain why Americans had become more obese. According to the abstract of their paper, "Why Have Americans Become More Obese?", Americans have become more obese over the past 25 years because they "have been consuming more calories. The increase in food consumption is itself the result of technological innovations which made it possible for food to be mass prepared far from the point of consumption, and consumed with lower time costs of preparation and cleaning. Price changes are normally beneficial, but may not be if people have self-control problems."[31] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||