|

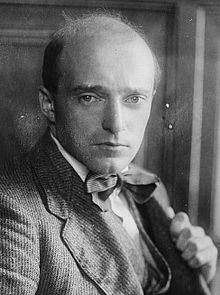

Erich Kleiber

Erich Kleiber (5 August 1890 – 27 January 1956) was an Austrian, later Argentine, conductor, known for his interpretations of the classics and as an advocate of Neue Musik. Kleiber was born in Vienna, and after studying at the Prague Conservatory, he followed the traditional route for an aspiring conductor in German-speaking countries of the time, starting as a répétiteur in an opera house and moving into conducting in increasingly senior positions. After holding posts in Darmstadt (1912), Barmen-Elberfeld (1919), Düsseldorf (1921) and Mannheim (1922) he was appointed in 1923 to the important post of musical director of the Berlin State Opera. In Berlin, Kleiber's scrupulous musicianship and enterprising programming won him a high reputation, but after the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, he resigned in protest against its oppressive policies, and left the country, basing himself and his family in Buenos Aires. For the rest of his career he was a freelance, guest conducting internationally in opera houses and concert halls. He played an important part in the creation of The Royal Opera in London, but a plan for him to return to the Berlin State Opera in the 1950s fell foul of politics. Kleiber was regarded as an outstanding conductor of Mozart, Beethoven and Richard Strauss and encouraged modern composers, including Alban Berg, whose Wozzeck he premiered. He died suddenly in Zürich at the age of 65. Life and careerEarly yearsKleiber was born in Wieden, Vienna, on 5 August 1890, the second of the two children of Dr Franz Otto Kleiber, a teacher, and his wife Vroni, née Schöppl.[1] Kleiber's father died in 1895 and his mother died the following year. Kleiber and his sister went to live with his maternal grandparents in Prague. In 1900, after the death of his grandfather, Kleiber returned to Vienna to live with an aunt and study at a Gymnasium. He was able to attend performances at the Musikverein, the Volksoper and Hofoper where Gustav Mahler was the musical director. With his friend Hans Gál, Kleiber heard a performance of Mahler's Sixth Symphony, conducted by the composer; at the end, Kleiber told Gál that he intended to be a conductor.[2] Gál pointed out that the traditional route to becoming a conductor was to start as a Korrepetitor (répétiteur) in one of the many opera houses in German-speaking countries, but Kleiber had never been taught to play the piano.[3] In July 1908 Kleiber left Vienna and studied art, philosophy, and art history at the Charles University in Prague.[4] On the strength of some compositions of his which he submitted to the Prague Conservatory he was admitted, with the proviso that unless he could reach the required standard within the year he would have to leave. He bought a piano and taught himself to play it, took organ lessons, and mastered the curriculum well enough to pass the conservatory's examinations.[5] He was taken on as a coach at the New German Theatre in 1911, and began to get work as an accompanist, working in 1912 with Alfred Piccaver.[6] The intendant of the Darmstadt Court Theatre spotted Kleiber's potential and invited him to conduct there. He worked at Darmstadt for seven years. Further appointments followed at Barmen-Elberfeld in 1919, Düsseldorf in 1921 and Mannheim in 1922.[4] BerlinAs the music director of the Berlin State Opera he championed works of Alban Berg and Darius Milhaud In 1923 Leo Blech resigned as musical director of the Berlin State Opera after 17 years in charge. Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer had been approached to succeed him, but the approaches were inconclusive. Kleiber, invited to conduct a single performance of Fidelio in August 1923, made a highly favourable impression, and three days later he was appointed to succeed Blech with a five-year contract.[7] Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians describes Kleiber's Berlin years as "exceptionally productive": In 1924 he conducted Janáček's Jenůfa in a production regarded as decisive for the composer's wider success. Krenek's Die Zwingburg was presented in the same year, followed in 1925 by the première of Berg's Wozzeck. Other new works he performed included Schreker's Der singende Teufel (1928) and Milhaud's Christophe Colomb (1930), and he also conducted Wagner's Das Liebesverbot and various operettas.[4]

In 1926, Kleiber married an American, Ruth Goodrich (1900–1967). They had two children, Veronica (1928–2017), later assistant to Claudio Abbado,[8] and a son Karl, later known as Carlos, (1930–2004), who became a celebrated conductor.[9][10] During his Berlin years Kleiber began an international career, conducting concerts in Buenos Aires (1926, 1927) and Moscow (1927); in New York he worked for six or seven weeks in the 1930–31 and 1931–32 seasons, giving between 20 and 30 concerts.[11] Kleiber's time in Berlin came to end in 1934, the year after the NSDAP (Nazi Party) came to power in Germany. Kleiber, who was not Jewish, politically active, or otherwise persona non grata with the Nazis, could have continued his career under their régime, but he would not accept their racial policies or their stifling of artistic freedom. When Berg's new opera Lulu was banned as Entartete Musik (degenerate music) Kleiber resigned from his post at the State Opera. He was outraged when Berg – a close friend – assumed that he had joined or would join the Nazi Party to safeguard his career. He wrote to Berg, "I was never a member of the NSDAP – and never had any intention of becoming one!!! Despite several requests!"[12] Prevented from performing Lulu, Kleiber made a gesture of defiance to the régime by putting the world premiere of the suite from the opera in the programme of the last concert he gave in Nazi Germany. The event attracted international attention. The New York Times reported For nearly fifteen minutes a huge audience numbering many members of the diplomatic corps, which listened with straining intensity cheered, stamped and applauded, recalling to the platform time and again Erich Kleiber, who prepared and conducted the stirring performance, the orchestra of the State Opera, and the Viennese light soprano Lillie Claus.[13]

Kleiber conducted the final opera performances to which he was contractually committed and then left Germany with his wife and children in January 1935.[14] EmigréKleiber's biographer John Russell entitles his chapter covering the years 1935 to 1939 "Vagabondage".[15] Kleiber made his British début with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1935, and was a frequent visitor to Amsterdam, Brussels and other European cities. In 1938, at the invitation of Sir Thomas Beecham, he appeared for the first time at Covent Garden, conducting Der Rosenkavalier with a starry cast headed by Lotte Lehmann.[a] He repudiated his contract with La Scala, Milan in April 1939, shortly after Mussolini's fascist régime enacted its own anti-semitic legislation. Kleiber said: I hear that access to the Scala is denied to Jews. Music, like air and sunlight, should be for all. When, in these hard times, this consolation is denied to human beings for reasons of race and religion, then I both as Christian and artist, feel that I can no longer co-operate.[17]

Insofar as Kleiber had a base during these years it was in Buenos Aires; he became an Argentine citizen in 1936.[9] He took charge of the German opera seasons at the Teatro Colón between 1937 and 1949, and conducted in Chile, Uruguay, Mexico and Cuba.[4] At the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, Kleiber conducted 29 different operas (a total of 181 performances) during 10 seasons (1937–41, 1943, and 1946–49). The operas he conducted the most were Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Der Rosenkavalier. The performances he conducted featured some of the world's top singers of German opera at the time, including for example Kirsten Flagstad, Astrid Varnay, Rose Bampton, Max Lorenz, Set Svanholm, René Maison, Hans Hotter and Alexander Kipnis. Kleiber conducted the Western Hemisphere's premiere of Die Frau ohne Schatten in Buenos Aires in 1949. [18] Post-warAfter the Second World War, Kleiber resumed his European activities, first with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1948, and at Covent Garden from 1950 to 1953. The post-war Covent Garden was very different from the star-studded international pre-war seasons. The new company, built from scratch with largely British singers, was not then of international calibre or even approaching it.[19] Kleiber's contribution was of crucial importance to the development of the company.[4] The record producer John Culshaw wrote: No one present will ever forget the transformation in the Covent Garden pit when, in the early nineteen-fifties, Erich Kleiber plunged into the Carmen prelude. Kleiber had not imported the Philharmonia for the occasion, nor had he filled the orchestra with specialist deputies; he had simply made the orchestra play precisely, rhythmically, and with a strict dynamic gradation. The effect of this, after years of sloppy, routine performances of Carmen, was a revelation.[20]

The Covent Garden management hoped Kleiber would become the company's musical director, but he was not willing to commit himself.[21] There were many competing demands for his services in Europe. At the 1951 Maggio Musicale in Florence, he conducted a celebrated production of Les vêpres siciliennes, starring Maria Callas, and the world premiere of Haydn's Orfeo ed Euridice (also with Callas), written 160 years earlier.[4] There were plans for his appointment to the Vienna Staatsoper, but they fell through, and his only operatic engagement in his native city was Der Rosenkavalier in 1951. In 1953 he conducted the complete Ring cycle in Rome; it was broadcast, but the recordings are thought to be lost.[22] Between 1948 and 1955 he recorded a range of works for the Decca record company.[23] Almost at the end of Kleiber's career there was a debacle after he accepted an invitation to resume his pre-war post at the Berlin Staatsoper. Following the post-war division of the city, the house was in East Berlin. The old building had been bombed and was slowly being restored. In 1951 the East German authorities invited Kleiber to become musical director when the rebuilding was complete. At the time, hostility between the Soviet bloc and the western allies was intense, and some ardent democrats thought Kleiber wrong to work for the totalitarian East German régime. The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra withdrew his invitation to conduct at its concerts, but he felt he was building bridges between east and west.[24] The reopening was scheduled for 1955, but as the time approached, Kleiber became increasingly aware of state interference in the running of the house. Matters came to a head when the authorities removed an old monument to Frederick the Great that was a key feature of the building. Kleiber wrote, "I have had to acknowledge that the spirit of the old theatre cannot reign in the new building", and he resigned before the re-opening. Feeling that the West Germans had been mean-minded in their attempt to stop him conducting in East Berlin, he left the city and never returned.[25]  In Russell's view the collapse of Kleiber's hopes for the Staatsoper was a blow from which he did not recover.[26] He died suddenly in Zürich on 27 January 1956, aged 65.[27] Reputation, honours and legacyIn the view of Grove, Kleiber was: outstanding as a conductor of Mozart, Beethoven and Richard Strauss, refusing to indulge in romantic interpretation as a means of self-projection, ignoring false performing traditions and studying the scores assiduously. He never lost his whole view of a work, and his approach was strictly non-sentimental. He won the lasting devotion of orchestral players as well as singers.[4]

Among the honours awarded to Kleiber were Commandeur Ordre de Léopold, Belgium; Commendatore della Corona d’ Italia; Orden el Sol de Peru; and Comendador del Merito, Chile.[9] Kleiber was a composer; among his works are a Violin Concerto, Piano Concerto, orchestral variations, Capriccio for Orchestra, numerous chamber music works, piano pieces, and songs.[4] RecordingsGrove comments that Kleiber's recordings of Der Rosenkavalier, Le nozze di Figaro and Beethoven's symphonies "all demonstrate his extraordinary rhythmic control and dynamic flexibility".[4] For more information on his Figaro recording, see Le nozze di Figaro (Kleiber recording). His recordings include the following, many of which have been reissued in digital transfers:

Filmography

Notes, references and sourcesNotes

References

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||