|

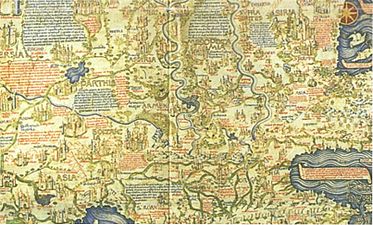

Fra Mauro map The Fra Mauro map is a map of the world made around 1450 by the Italian (Venetian) cartographer Fra Mauro, which is “considered the greatest memorial of medieval cartography."[1] It is a circular planisphere drawn on parchment and set in a wooden frame that measures over two by two meters. Including Asia, the Indian Ocean, Africa, Europe, and the Atlantic, it is orientated with south at the top. The map is usually on display in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice in Italy. The Fra Mauro world map is a major cartographical work.[2] It took several years to complete and was very expensive to produce. The map contains hundreds of detailed illustrations and more than 3000 descriptive texts. It was the most detailed and accurate representation of the world that had been produced up until that time. As such, the Fra Mauro map is considered one of the most important works in the history of cartography. According to Jerry Brotton, it marked "the beginning of the end of early medieval mappae mundi that reflected biblical geographical teaching." It placed accuracy ahead of religious or traditional beliefs, breaking with tradition, for example, by not placing Jerusalem at the center of the world and not showing a physical location for the biblical Paradise.[3] The maker of the map, Fra Mauro, was a Camaldolese monk from the island of Murano near Venice. He was employed as an accountant and professional cartographer. The map was made for the rulers of Venice and Portugal, two of the main seafaring nations of the time. The map The map is very large – the full frame measures 2.4 by 2.4 metres (8 by 8 ft). This makes Fra Mauro's mappa mundi the world's largest extant map from early modern Europe. The map is drawn on high-quality vellum and is set in a gilded wooden frame. The large drawings are highly detailed and use a range of expensive colors; blue, red, turquoise, brown, green, and black are among the pigments used. The main circular map of the world is surrounded by four smaller spheres:

About 3000 inscriptions and detailed texts describe the various geographical features on the map, as well as related information about them. The depiction of inhabited places and mountains, the map's chorography, is also an important feature. Castles and cities are identified by pictorial glyphs representing turreted castles or walled towns, distinguished in order of their importance. The making of the map was a major undertaking and the map took several years to complete. The map was not created by Fra Mauro alone, but by a team of cartographers, artists, and copyists led by him and using some of the most expensive techniques available at the time. The price of the map would have been about an average copyist's annual salary.[3] Editions and reproductionsThe studio of Fra Mauro produced two original editions of the map. In addition, at least one high-quality physical reproduction is made on the same material.

In 1804, the British cartographer William Frazer made a full reproduction of the map on vellum. Although the reproduction is exact, minor differences are seen between the Venetian original and the British copy. The Frazer reproduction is currently on display in the British Library in London. In this article, some images are from the Venetian edition and some are from the Frazer reproduction. A number of historians of cartography, starting with Giacinto Placido Zurla (1806), have studied Fra Mauro's map.[5] A critical edition of the map was edited by Piero Falchetta in 2006. Orientation and centerThe Fra Mauro world map is unusual, but typical of Fra Mauro's portolan charts, in that its orientation is with the south at the top. One explanation for why the map places south at the top is that 15th-century compasses were south-pointing.[6] In addition, south at the top was used in Arab maps of the time. In contrast, most European mappae mundi from the era placed east at the top, since east was the direction of the biblical Garden of Eden. Other well-known world maps of the time such as the Ptolemy map places the north at the top. Fra Mauro was aware of the religious importance of the east, as well as of the Ptolemy map, and felt the need to defend why he changed the orientation in his new world map:

In another break from tradition, Jerusalem is not shown as the center of world. Fra Mauro justifies the change in this way:

EuropeThe European part of the map, closest to Fra Mauro's home in Venice, is the most accurate. The map depicts the Mediterranean, the Atlantic coast, the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea and extends as far as Iceland. The coasts of the Mediterranean are very accurate and every major island and land mass is depicted. Many cities and rivers, and mountain ranges of Europe are included. Great BritainTwo legends on the map describe England and Scotland. They talk about giants, the Saxons, Saints Gregory and Augustine:[2]

This account is likely based on the Historia Regum Britanniae, a famous book created in the 1100s that writes about the early kings of England, famous for being one of the first texts to include King Arthur. It outlines the same story stating that Brutus, the descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, flees Rome to conquer Britain from its native inhabitants, the Giants.[7]

ScandinaviaScandinavia is the least accurate part of the European section. A legend describing Norway and Sweden describes tall, strong and fierce people, polar bears and St. Bridget of Sweden:[2]

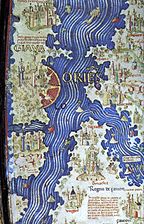

AsiaThe Asian part of the map shows the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, the Indian subcontinent including the island of Sri Lanka, and the islands of Java and Sumatra, as well as Burma, China, and the Korean peninsula. The Caspian Sea, which is bordering Europe, has an accurate shape, but the outline of Southern Asia is distorted. India has been split in two halves. Major rivers such as the Tigris, the Indus, the Ganges, the Yellow, and the Yangtze are depicted. Cities include Baghdad, Beijing, Bokhara, and Ayutthaya. JapanThe Fra Mauro map is one of the first Western maps to represent the islands of Japan (possibly after the De Virga world map). A part of Japan, probably Kyūshū, appears below the island of Java, with the legend "Isola de Cimpagu" (a misspelling of Cipangu). Africa The description of Africa is reasonably accurate.[10] Some of the islands named in the area of the southern tip of Africa bear Arabian and Indian names: Nebila ("celebration" or "beautiful" in Arabic), and Mangla ("fortunate" in Sanskrit). These are normally identified as the "Islands of Men and Women" mentioned under § Indian Ocean. According to an old Arabian legend as retold by Marco Polo, one of these islands was populated exclusively by men and the other was populated exclusively by women, and the two would only meet for conjugal relations once a year. Their location was not certain and the location proposed by Fra Mauro is but one of multiple possibilities: Marco Polo himself located them in the neighborhood of Socotra, and other medieval cartographers offered locations in Southeast Asia, near Singapore or in the Philippines. The islands are generally thought to be mythical.[11] Indian OceanThe Indian Ocean is accurately depicted as connected to the Pacific. Several groups of smaller islands such as the Andamans and the Maldives are shown. Fra Mauro puts the following inscription by the southern tip of Africa, which he names the "Cape of Diab", describing the exploration by a ship from the east around 1420:[8][9]

Fra Mauro explained that he obtained the information from "a trustworthy source", who traveled with the expedition, possibly the Venetian explorer Niccolò de' Conti, who happened to be in Calicut, India, at the time the expedition left:

Fra Mauro also comments that the account of the expedition, together with the relation by Strabo of the travels of Eudoxus of Cyzicus from Arabia to Gibraltar through the southern ocean in antiquity, led him to believe that the Indian Ocean was not a closed sea and that Africa could be circumnavigated by her southern end (Text from Fra Mauro map, 11, G2). This knowledge, together with the map depiction of the African continent, probably encouraged the Portuguese to intensify their ultimately successful effort to round the tip of Africa. AmericasOther than Greenland, the Americas were unknown to Europeans in 1450. Greenland is included in the map as a reference to Grolanda.[2] Circumference of the EarthAs was generally the case among medieval scholars, Fra Mauro regarded the world as a sphere. However, he used the convention of describing the continents surrounded by water within the shape of a disc. In one of the texts, the map includes an estimate of the circumference of the earth:

Miglia is Italian for miles, a unit that was invented by the Romans but which had not yet been standardized in 1450. If miglia is taken as the Roman mile, this means the circumference would be about 34,468 km. If miglia is taken as the Italian mile, the stated circumference would be about 43,059 km. The actual meridional circumference of the Earth is close to both these values at about 40,008 km or approximately 24,860 English miles. So the stated range taken in Roman miles is 86-92% of modern measurements, whereas taken in Italian miles is 108-115% of the current measurement.[12] SourcesThe sources for the map were existing maps, charts, and manuscripts, which were combined with written and oral accounts of travelers. The text on the map mentions many of these travel accounts. Some of the main sources were accounts of the journeys of Italian merchant and traveller Niccolò de' Conti. Setting out in 1419, De Conti traveled throughout Asia as far as China and present-day Indonesia during a period of 20 years. In the map, many new location names and several verbatim descriptions were taken directly from de Conti's account. The "trustworthy source" whom Fra Mauro quotes is thought to have been de' Conti himself. The book of travels of Marco Polo is also believed to be one of the most important sources of information, in particular about East Asia. For Africa, Fra Mauro relied on recent accounts of Portuguese exploration along the west coast. The detailed information on the southeastern coast of Africa, was likely brought by an Ethiopian embassy to Rome in the 1430s. Fra Mauro also probably relied on Arab sources. Arab influence is suggested by the north-south inversion of the map, an Arab tradition exemplified by the 12th-century maps of Muhammad al-Idrisi. As Piero Falchetta notes, many geographical facts are reflected in Fra Mauro map for which what Fra Mauro's source was is not clear, as no similar information is found in other preserved Western maps or manuscripts of the period.[13] This situation can be at least partially explained by the fact that, besides the existing maps and manuscripts, important sources of information for his map were oral accounts from travelers – Venetians or foreigners – coming to Venice from all parts of the then-known world. The importance of such accounts is indicated by Fra Mauro himself in a number of inscriptions.[14] An even earlier map, the De Virga world map (1411–1415) also depicts the Old World in a way broadly similar to the Fra Mauro map, and may have contributed to it.[15] Gallery

See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Map of the world by Fra Mauro, 1459. Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|