|

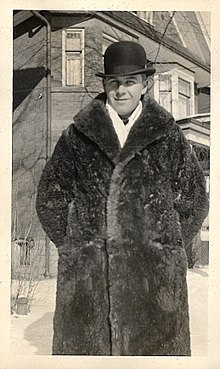

Harold Ballard

Harold Edwin Ballard (born Edwin Harold Ballard, July 30, 1903 – April 11, 1990) was a Canadian businessman and sportsman. Ballard was an owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League (NHL) as well as their home arena, Maple Leaf Gardens. A member of the Leafs organization from 1940 and a senior executive from 1957, he became part-owner of the team in 1961 and was majority owner from February 1972 until his death. He won Stanley Cups in 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1967, all as part-owner. He was also the owner of the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League (CFL) for 10 years from 1978 to 1988, winning a Grey Cup championship in 1986. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame (1977) and the Canadian Football Hall of Fame (1987). His is one of seven names to be on both the Stanley Cup and Grey Cup. Early yearsBallard was born in Toronto, Ontario, Canada as Edwin Harold Ballard. He later reversed the names and referred to himself as Harold E. Ballard. For six years before World War I, Ballard and his family lived in Norristown, Pennsylvania. They returned to Toronto where his father, English-born Sidney Eustace Ballard, founded Ballard Machinery Supplies Co., a sewing machine manufacturer, which at one point was one of Canada's leading manufacturers of ice skates (it went out of the business in the early 1930s, when the Canadian skate market was dominated by CCM). Harold attended Upper Canada College as a boarding student until dropping out in his third year in 1919. Ballard became a fan of speed skating and would attend skating events and hockey games, helping to promote the Ballard skates. For the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland, Ballard was appointed assistant manager of the Varsity Grads team that won the hockey gold medal. As a member of the National Yacht Club, Ballard became an avid racer of Sea Fleas, small outboard hydroplanes. He competed in several regattas, and won the Toronto-Oakville marathon in 1929. Ballard was elected to the Yacht Club's executive committee in January 1930. He participated in the 133-mile Albany, New York-New York City marathon in April 1930, finishing second in his class. About a month later, Ballard and two friends from the Yacht club were hurled from a boat into a frigid Lake Ontario. Ballard was pulled from the water unconscious, but one of his friends died. None of the three was wearing a life jacket. Hockey coach and managerFollowing the 1930 racing season, the Yacht Club sponsored a senior team in the Ontario Hockey Association called the Toronto National Sea Fleas. Ballard was made business manager. Under coach Harry Watson, the team won the Allan Cup in 1932. Watson chose not to return the following season, and Ballard took over the coaching duties. At first, the players welcomed Ballard behind the bench, but the mood soon changed, particularly after Ballard benched the team captain. That triggered a mutiny among some of the team's top players, who resigned from the squad in November. The team had a poor year with Ballard coaching, but Ballard arranged a European tour for the Nationals which included competing in the 1933 Ice Hockey World Championships in Prague. There, the Nationals lost 2–1 in overtime to a team from the U.S.—the first loss for a Canadian team at the world championships. While touring Europe, the Nationals were involved in several fights, both on the ice and off. In one incident, Ballard was arrested in Paris following a fracas at a hotel. The tour marked the end of Ballard's career as a full-time hockey coach. In 1934, Ballard became manager of the West Toronto Nationals OHA junior team and hired Leaf captain Hap Day as coach. When Day was busy with the Leafs and unavailable for games, Ballard would step behind the bench as acting coach. Under Day and Ballard, the Nationals won the Memorial Cup at the end of the 1935–36 season. The following season, Day and Ballard worked together to run a senior team sponsored by E. P. Taylor's Dominion Brewery. At the same time, Ballard continued to work for Ballard Machinery, and took over the business after his father's retirement in 1935. After Day became coach of the Leafs in 1940, he recommended Ballard to the Leaf organization to run the Toronto Marlboros, the senior and junior teams owned by the Leafs. Ballard was made president and general manager. He would coach one more game, for the senior Marlies, during the 1950 Allan Cup final, after head coach Joe Primeau's father died. The Marlboros lost the game but won the series and the championship. In the early 1950s, Ballard hired his long-time friend Stafford Smythe, son of Leafs owner Conn Smythe, as managing director of the Marlboros. The Marlies won the Memorial Cup in 1955—their first championship in 26 years—and repeated the feat the following season. In 1944, Ballard formed Harold E. Ballard Ltd., the personal holding company he would later use to hold his interest in Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. Joins the Maple LeafsIn 1957, Ballard moved up to the Maple Leafs as a member of a committee chaired by Stafford Smythe which oversaw hockey operations after Conn Smythe stepped down as general manager and Hap Day was pushed out of the Leafs organization. Ballard wasn't initially named to the committee when it was unveiled in March 1957, but took the place of Ian Johnston nine months later. At age 54, Ballard was the oldest member of the group, which were otherwise all in their 30s and 40s. The committee came to be known as the "Silver Seven". During the hockey off-season in 1961, Ballard became founding president of the four-team Eastern Canada Professional Soccer League, which operated in Toronto, Hamilton, and Montreal. Steve Stavro, who would succeed Ballard as Leafs owner 30 years later, was co-owner of the Toronto City team.[1] For the 1962 season, Ballard tried to introduce a hockey-style penalty box to soccer, but the rule change was not allowed by FIFA. Partner in Leafs ownership groupIn November 1961, Conn Smythe sold most of his shares in Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. to a consortium of his son Stafford, Toronto Telegram owner John W. H. Bassett, and Ballard. Ballard fronted Stafford Smythe most of the $2.3 million purchase price. Conn Smythe later claimed that he believed he was only selling his shares to his son, but it is very unlikely that Stafford could have acquired the millions he needed to buy the Leafs on his own. As a reward for his role in the purchase, Ballard was named executive vice president of Maple Leaf Gardens, alternate governor of the Maple Leafs and chairman of the team's hockey committee. He played a key role in the Leaf dynasty of the 1960s, winning Stanley Cups in 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1967. However, Ballard soon began displaying tendencies that would eventually make him one of the most detested owners in NHL history.[2] Just after the advent of colour television in Canada, the Maple Leafs installed a new lighting system. While it provided a clearer picture for fans, it caused a very sharp glare that distracted players. Ballard's solution was to make the CBC pay for the upgrade. When Hockey Night in Canada′s president, Ted Hough, balked at Ballard's demands just before a broadcast, Ballard grabbed a fireman's ax and threatened to cut the TV cable unless Hough agreed to pay. Hough relented, and the broadcast went on as scheduled.[3] Ballard's greatest influence in this period was not on the ice, but on the financial performance of Maple Leaf Gardens. Within three years under the new owners, profits at the Gardens had tripled to just under $1 million. He negotiated lucrative deals to place advertising throughout the building, and greatly increased the number of seats in the Gardens. To make room for more seats, Ballard removed a large portrait of Queen Elizabeth II from the Gardens. When asked about it, Ballard replied "She doesn't pay me, I pay her. Besides, what the hell position can a queen play?"[4] He also expanded the number of concerts, entertainment acts, and conventions booked in the building. Ballard booked The Beatles on each of their three North American tours from 1964 to 1966. On the second tour, in 1965, Ballard sold tickets for two shows, even though the agreement had been for only one. On the hot summer day of one of the concerts, Ballard ordered the building's heat turned up, shut off the water fountains, and also delayed both of the concerts for over an hour. The only available refreshments were large soft drinks from the concession stands.[5] In 1969, Ballard and Stafford Smythe were charged with tax evasion and accused of using Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. to pay for their personal expenses. Bassett, who had by this time become chairman of the board, received the support of the board of directors in an 8–7 vote to fire Smythe and Ballard. However, Bassett didn't force Smythe and Ballard to sell their shares, and both men remained on the board. This proved to be a serious strategic blunder, as Smythe and Ballard controlled almost half the company's shares between them. A year later, they staged a proxy war to regain control of the board. Ballard was reappointed executive vice president. Facing an untenable situation, Bassett resigned as chairman and sold his shares to Ballard and Stafford Smythe in September 1971. Smythe died just six weeks later. At age 68, Ballard won a battle with Stafford's family and bought his shares, giving him a 60 percent controlling interest in the Gardens. He installed himself as president and chairman of Maple Leaf Gardens and governor of the Maple Leafs. Leafs under Ballard's sole ownershipCriminal trial and the Summit SeriesShortly after taking control of the Leafs, Ballard stood trial on 49 counts of fraud, theft and tax evasion involving $205,000. He was accused by the Crown attorney of using funds from Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. to pay for renovations to his home on Montgomery Rd., in Etobicoke. Funds were also used to renovate his Midland cottage, to rent limousines for his daughter's wedding in 1967, and to buy motorcycles for his sons (passing off the expense as hockey equipment for the Marlboros), as well as placing money belonging to the corporation into a private bank account that he controlled along with Stafford Smythe. Ballard pleaded not guilty to all charges. At the same time, Hockey Canada and the NHL Players Association had negotiated an agreement to hold an eight-game tournament between Canadian professional hockey players and the top players from the Soviet Union. The tournament would become known as the Summit Series. Just as Ballard's trial was beginning, he told Hockey Canada that they were welcome to use any member of the Leafs on the Canadian team, could use Maple Leaf Gardens for their training camp, and could use the building for any or all of the games in the series, with the Gardens' share of the gate receipts being donated to the NHL players' pension fund. Ballard then partnered with long-time rival Alan Eagleson and Eagleson's client Bobby Orr to get the television rights to the series, which would be used to benefit Hockey Canada and the players' union. At no time before or after his trial did Ballard show any interest in being associated with Eagleson or in having members of the Leafs play the Soviets, and the move was widely seen to be a means to generate favourable public relations. At the conclusion of the series, Ballard sent a bill to Hockey Canada for use of the building. In August, just weeks before the series began, Ballard was convicted on 47 of the charges. Two months later, he was sentenced to nine years in a federal penitentiary. After a brief stay at Kingston Penitentiary, he was moved to a minimum-security facility that was part of Millhaven Institution. He finished his sentence at a halfway house in Toronto, and was paroled in October 1973 after serving a third of his sentence. After his parole, he stated that prison life was like staying in a motel, with colour television, golf, and steak dinners. Ballard even claimed to possess photographs of himself drinking beer with corrections officers and wearing one of their uniforms.[6] During the time Harold was in prison, his son Bill managed Maple Leaf Gardens. Team management Ballard was a very hands-on owner who quickly became known for being irascible and cantankerous. He tried to micromanage the team, interfering with coaches and players. Soon after taking over as majority owner, he forced out several longtime front-office personnel and replaced them with his own men. For example, he cut the salary of chief scout and former Leafs star Bob Davidson by almost two-thirds, forcing Davidson to resign. Davidson had served in the Leafs organization for almost 40 years in various capacities. Ballard's opposition to European players was so virulent that a Leafs scout used Ballard's time in jail to sign Börje Salming, one of the NHL's first great European players. After Ballard took control during the 1971–72 season, one of the first challenges he faced was the creation of the World Hockey Association (WHA) as a competitor to the NHL. At the time, NHL teams relied on the reserve clause to keep players from jumping to other teams in the league, but the clause could not prevent players from leaving the NHL to join a different league. At the end of the 1971–72 season, the Leafs only had three players signed to contracts for the next season: Rick Kehoe and veterans Jacques Plante and Bobby Baun. But Ballard did not take the unproven WHA seriously as a competitor and so was outbid on the services of several players in the Leafs organization. The biggest loss was goaltender Bernie Parent, a superstar in the making, who was offered a WHA contract with financial terms far beyond what Ballard was prepared to match. Along with Parent, Rick Ley, Jim Harrison, Brad Selwood, and Guy Trottier all left the Leafs for the WHA before the 1972–73 season, as did some minor league prospects in the Leafs' system as well as the team's minor league coach, Marcel Pronovost. Paul Henderson and Mike Pelyk followed a year later. The players who stayed could use the threat of joining the WHA to negotiate better contracts, and Ballard always blamed the WHA for inflating players' salaries. Ballard never forgave the WHA for this, and became the leader of the hardline faction of NHL owners who opposed any merger with the upstart league. In 1973, the WHA moved the Ottawa Nationals to Toronto as the Toronto Toros. A year later, they moved to the Gardens. Toros owner John F. Bassett (son of the elder John Bassett) had negotiated a lease with the elder Ballard's son, Bill. However, by the time the Toros played their first game at the Gardens, Ballard had been released from prison. Angered that the WHA was literally in his backyard, the elder Ballard made the Toros' lease terms as onerous as possible. This became clear when the arena was dim for the first game. When an outraged Bassett complained, Ballard demanded $3,500 for use of the lights. He also removed the cushions from the home bench for Toros' games (he told an arena worker, "Let 'em buy their own cushions!") and denied them access to the Leafs locker room. These demands made it financially impossible for the Toros to survive in Toronto, and after the 1975-76 season they moved to Birmingham, Alabama.[7] When the NHL finally did take in four WHA teams after the 1978–79 season, Ballard refused to support the deal. He was not only angry at how the WHA had decimated his roster earlier in the decade, but also wasn't enamored at the prospect of reduced television revenue. The WHA had insisted on bringing in all three of its surviving Canadian teams, meaning revenue from CBC telecasts now had to be split six ways rather than three.[8] At the time Ballard took over, the Leafs' captain was Dave Keon, who had been with the team since 1960. Ballard and Keon never got along, and when Keon's contract expired in 1975, Ballard let it be known that Keon had no place on the team. However, he insisted on being compensated for Keon's rights, and at the time there were no exceptions in the NHL's reserve clause to fix or limit the level of compensation an owner could demand. Ballard set the price so high that potential suitors shied away, in effect preventing Keon from joining another NHL team. Keon was able to join the WHA's Minnesota Fighting Saints, since the WHA had refused to recognize the reserve clause and successfully fought off an NHL lawsuit (championed in particular by Ballard) over the matter. When the Fighting Saints folded, Keon received an offer from the soon-to-be dynasty New York Islanders, but Ballard still owned Keon's NHL rights and effectively blocked that deal, compelling Keon to move to the relatively stable New England Whalers. Even after the NHL-WHA merger was finalized over Ballard's objections, it was only the intervention of NHL President John Ziegler that finally persuaded Ballard to not reclaim Keon's rights (which would have effectively ended his career) and allow him to play three more seasons with the mediocre Hartford Whalers. Keon never forgave Ballard for how he had been treated, and it was more than 20 years before he was reconciled with the Leafs.[9] During the 1978–79 season, with the Leafs struggling to make the playoffs, Ballard fired the team's popular head coach, Roger Neilson, against the wishes of the players. Two days later, Ballard asked Neilson to return, but with a paper bag over his head so as to conceal his identity. Neilson did return, without the paper bag.[10] After the season, where the Maple Leafs were swept in the quarterfinals by the Canadiens, Ballard fired general manager Jim Gregory, replacing him with his predecessor, Punch Imlach.[11] Gregory learned of the news when he received a call from an NHL executive offering him the directorship of the NHL Central Scouting Bureau, unbeknownst to him that Ballard had fired him.[11] Relationship with SittlerBallard's desire to control players and their salaries also put him at odds with Alan Eagleson, executive director of the NHL Players' Association and a player agent whose clients included Keon's successor as captain, Darryl Sittler. Ballard had once called Sittler "the son I never had", but relations between the two took a turn for the worse with Sittler's increasing prominence in the NHLPA. Around that time, the Leafs had made it as far as the Stanley Cup semifinals in 1978, losing to the two-time defending champions Montreal Canadiens. This led to renewed criticism of Ballard's unwillingness to spend what it took to get the Leafs to the next level. In July 1979, Ballard brought his longtime friend, Imlach, back to the organization as general manager. Imlach was as staunchly anti-union as Ballard; during his first stint in Toronto, he had been one of Eagleson's most ardent foes. With Ballard's support, Imlach moved to dismantle the roster and undermine Sittler's influence, despite many analysts viewing the team as having a promising future. Sittler was apparently untouchable as he had a no-trade clause in his contract and, through his agent Eagleson, had insisted on $500,000 to waive it. When the Leafs traded Sittler's close friend Lanny McDonald to the moribund Colorado Rockies on December 29, 1979, a member of the Leafs anonymously told the Toronto Star that Leafs management would "do anything to get at Sittler"[12] and was bent on undermining the captain's influence on the team. Angry teammates trashed their dressing room in response. Sittler himself ripped the captain's C off his sweater, later commenting that a captain had to be the go-between with players and management, and he no longer had any communication with management.[13] Ballard would liken Sittler's actions to burning the Canadian flag.[14] Eagleson called the trade "a classless act."[12] Through the summer of 1980, Ballard insisted that Sittler would not be back with the Leafs. As Imlach was preparing to trade Sittler to the Quebec Nordiques, he had a heart attack in August and was hospitalized. Ballard used the opportunity to name himself acting general manager and hold talks with Sittler, and the two agreed that Sittler would return to the team for the 1980–81 season. The two men appeared together at a news conference described as "all smiles and buddy-buddy"[15] to announce that Sittler would not only be at training camp, but had reassumed his captaincy.[15] Ballard told the press that the real battle had been between Imlach and Eagleson, and Sittler just got caught in the crossfire. Ballard also signed Börje Salming to a new contract with terms that Imlach had refused to offer. Ballard remained as de facto general manager even when Imlach recovered. In September 1981, after Imlach had another heart attack during training camp, Ballard told the media that Imlach's poor health meant that "he's through as general manager". Imlach was never officially fired, but when he tried to return to his office in November, he found that his parking spot at Maple Leaf Gardens had been reassigned and Gerry McNamara had been made acting general manager. Imlach never returned to work and his contract was allowed to expire. Though Imlach was gone, Sittler's relationship with the Leafs worsened again in the 1981–82 season and he was traded that year to the Philadelphia Flyers. 1980sThe McDonald trade sent the Leafs into a downward spiral. Even with the inclusion of what were effectively four expansion teams as per the terms of the "merger" with the WHA, the Leafs finished five games below .500 in 1980, although it was still good enough for a playoff berth. They would not post a winning record again in Ballard's lifetime, going a franchise-record 13 consecutive seasons without a winning record. The low point came in 1984–85, when the Leafs finished the season with the worst record in the league, 32 games below .500. Their .300 winning percentage was the second-worst in franchise history. They nearly duplicated that dubious achievement in 1987–88. That year, they finished with a .325 winning percentage, fourth-worst in franchise history, and were only one point up on the Minnesota North Stars for the league's worst record. Nevertheless, they still qualified for the playoffs under the playoff format in use at the time. In those days, the top four teams in each division made the playoffs, regardless of record. The Leafs and North Stars both played in the Norris Division, which was extremely weak that year; the Red Wings were the only team with a winning record. The Leafs defeated the Red Wings in the final game of the season, and backed into the playoffs when the Stars lost their final game hours later. It was the second time in three years that they had made the playoffs despite finishing with a winning percentage below .400. In 1985-86, they finished with a .356 winning percentage, the fourth-worst record in the league and fourth worst in franchise history. However, due to playing in a division where no team cracked the 90-point barrier, they still made the playoffs. Subsequent league expansions and format revisions make it impossible for a team so close to the bottom of the league standings to qualify for the playoffs today. All told, the Leafs only had six winning seasons in Ballard's 18-plus seasons as majority owner, and never finished higher than third in their division in any format. In Ballard's last 13 seasons, they only finished above fourth once and won only two playoff series. Many fans consider the Ballard era to be the darkest period in team history. Off the ice, the Maple Leafs under Ballard were one of the league's most financially successful teams. However, this was largely because Ballard was unwilling to increase the payroll in order to improve the on-ice product, despite playing in the fourth-largest market. Even though the Leafs were barely competitive for much of the latter part of Ballard's tenure, every game at Maple Leaf Gardens was sold out. Ballard thus felt he had little financial incentive to sign better players. However, many players were unwilling to sign with Toronto in any event because of Ballard's reputation. Ballard famously had his hand and footprints etched onto a concrete slab and placed it at centre ice of Maple Leaf Gardens, which deteriorated the quality of the Gardens ice. Maple Leaf Gardens under BallardAfter Ballard's release from prison, he had an apartment built at the Gardens facing Church Street where he would live through most of the year, while spending summers at his cottage near Lafontaine, Ontario in the Thunder Beach community. The storied arena fell into disrepair during Ballard's tenure. For example, when the roof leaked, he did little more than order plastic sheets to catch the rainwater. Other incidents and anecdotesOther notable incidents and anecdotes during Ballard's time as majority owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs and Maple Leaf Gardens include:

Other involvementsCanadian Football LeagueIn the early 1970s, Ballard made an application for a second Canadian Football League team to be based in Toronto, to play at Varsity Stadium. At the time, the CFL still consisted of two autonomous conferences. Ballard's application would have required the unanimous consent of the four Eastern Football Conference owners to have been approved under the rules in effect at the time. In the West, CFL teams had come under significant pressure resulting from the introduction of WHA franchises in the four largest Western markets, therefore Western Football Conference teams were generally supportive of Ballard's efforts to become a CFL owner. However, hostility to Ballard's overture from the Toronto Argonauts (then owned by Ballard's former partner John W. H. Bassett) ensured it never went anywhere. In 1974, when Bassett put the Toronto Argonauts up for sale, Ballard offered to buy the team for $3 million, but his offer was rejected. Shortly after, Ballard tried to buy the Hamilton Tiger-Cats from owner Michael DeGroote, but that offer was also rejected. Three money-losing seasons later, in January 1978, DeGroote contacted Ballard and sold him the club for $1.3 million.[24] Federal Labour Minister John Munro—from Hamilton—led an unsuccessful campaign against the deal, while Bassett, having sold the Argos to William R. Hodgson by this time, was also unable to intervene. Later that year, Ballard blocked Bassett's attempt to repurchase the Argos. However, Ballard did not object the following year when Hodgson sold his stake in the Argos to Carling O'Keefe notwithstanding the fact the brewer also owned a team in the WHA (the Quebec Nordiques). The Tiger-Cats made the playoffs every year under Ballard's ownership and played in four Grey Cup championship games, losing in 1980, 1984 and 1985 before finally winning the Cup in 1986. As owner of the Tiger Cats, Ballard claimed to be losing a million dollars a year.[25] In 1986, Ballard publicly called the Tiger Cats a bunch of overpaid losers.[25] After the Tiger Cats beat the Toronto Argonauts in the 1986 Eastern Final, Ballard said "You guys may still be overpaid, but after today, no one can call you losers."[25] A few days later, the Tiger Cats won the 1986 Grey Cup by beating the Edmonton Eskimos 39–15 and Ballard said it was worth every penny. During his tenure as owner of the Tiger-Cats, Ballard for a short time had the Tiger-Cats logo painted at centre ice of Maple Leaf Gardens in place of the blue Maple Leaf. Ballard sold the team to businessman David Braley on February 24, 1989. During his tenure, he repeatedly threatened to move the franchise to Toronto (70 km north). He had claimed losses in excess of $20 million over 11 seasons with the Tiger-Cats.[26] Major League BaseballIn the 1970s, Ballard had also bankrolled a group, headed by Hiram Walker Distillers vice-president Lorne Duguid, intent on bringing Major League Baseball to Toronto.[27] According to Duguid, Ballard had been willing to pay as much as $15 million so he could buy and relocate the San Francisco Giants to Toronto, even though the franchise was only worth around $8 million.[28] However, in the end, it was a partnership of the Labatt Brewing Company, Howard Webster, and the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) that brought baseball to Toronto, as they were awarded an expansion team in the American League for $7 million that became the Toronto Blue Jays, who began play in 1977.[29] SupportersDespite his reputation, Ballard was well known for his charitable activities, and even leased out MLG for many functions. He was recognized for this on his citation during his 1977 Hockey Hall of Fame induction. However, as Ken Dryden put it in his book The Game, he seemed "like [a] wrestling villain who touches the audience to make his next villainy seem worse." Dave "Tiger" Williams who played with the Leafs from 1973 to 1980 had a close relationship with Ballard. Years later, Williams would remark that all Ballard would want from his players was an honest day of hard work. In gratitude, Williams shot a bear during a winter hunt and skinned it for Ballard's office. Death and estateBallard died from various health complications on April 11, 1990, at the age of 86.[30] Even before his death, there had been battles between his children, Bill Ballard, Harold Ballard Jr., and Mary Elizabeth Flynn, and his longtime companion, Yolanda Ballard. Although she and Harold never married, Yolanda had her name legally changed. She claimed to have been with Ballard for eight years at the time of his death. Yolanda's lawyer Howard Levitt stated there had been a marriage proposal.[31] In 1989, Bill Ballard was convicted of assaulting Yolanda and fined $500. Yolanda was not invited to Ballard's funeral, nor to the reading of his will. She fought with Ballard's family and partners over Ballard's estate following his death. In his will, Ballard had left Yolanda $50,000 a year for the rest of her life, but she considered this inadequate and sued for $192,600 and later $381,000 a year. The court awarded her $91,000.[32] According to Ballard's lawyer, his estate was worth less than $50 million. Most of the money was left to a charitable foundation. Ballard left his personal belongings to his children and grandchildren. Ballard's three children had all previously received shares in Maple Leaf Gardens that they sold for more than $15 million each. The executors of Ballard's will were Steve Stavro, Don Giffin and Don Crump. In 1991, Stavro paid off a $20 million loan that had been made to Ballard in 1980 by Molson. In return, he was given an option to buy Maple Leaf Gardens shares from Ballard's estate. Molson also agreed to sell its stake in Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. to Stavro. That deal closed in 1994, and shortly after Stavro bought Ballard's shares from the estate for $34 a share or $75 million.[33] The purchase was the subject of a securities commission review and a lawsuit from Ballard's son Bill, but the deal stood and Stavro and his partners in MLG Ventures became the new owner of the Leafs and Maple Leaf Gardens. Ballard is buried at Park Lawn Cemetery in Toronto with his wife Dorothy. References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||