|

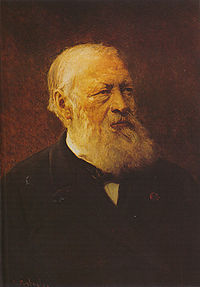

Hendrik Conscience

Henri (Hendrik) Conscience (3 December 1812 – 10 September 1883) was a Belgian author. He is considered the pioneer of Dutch-language literature in Flanders, writing at a time when Belgium was dominated by the French language among the upper classes, in literature and government.[1] Conscience fought as a Belgian revolutionary in 1830 and was a notable writer in the Romanticist style popular in the early 19th century. He is best known for his romantic nationalist novel, The Lion of Flanders (1838), inspired by the victory of a Flemish peasant militia over French knights at the 1302 Battle of the Golden Spurs during the Franco-Flemish War. Over the course of his career, he published over 100 novels and novellas and achieved considerable popularity.[1] After his death, with the decline of romanticism, his works became less fashionable but are still considered as classics of Flemish literature.[1] Early lifeChildhoodHendrik was the son of a Frenchman, Pierre Conscience, from Besançon, who had been chef de timonerie (wheelhouse master) in the navy of Napoleon Bonaparte, and who was appointed under-harbourmaster at Antwerp in 1811, when that city formed part of France. Hendrik's mother was a Fleming, Cornelia Balieu, and was illiterate.[1] When, in 1815, the French abandoned Antwerp after the Congress of Vienna, Pierre Conscience stayed behind. He was an eccentric and he took up the business of buying and breaking-up worn-out vessels, which the port of Antwerp was full of after the peace.[2] The child grew up in an old shop stocked with marine stores, to which the father afterwards added a collection of unsellable books; among them were old romances which inflamed the fancy of the child. His mother died in 1820, and the boy and his younger brother had no companion other than their grim and somewhat sinister father. In 1826 Pierre Conscience married again, this time a widow much younger than himself, Anna Catherina Bogaerts.[2] Hendrik had long before this developed a passion for reading, and reveled all day long among the ancient, torn and dusty tomes which passed through the garret of The Green Corner on their way to being destroyed. Soon after his second marriage Pierre took a violent dislike of the town, sold the shop and retired to the Campine (Kempen) region which Hendrik Conscience so often describes in his books; the desolate flat land that stretches between Antwerp and Venlo. Here Pierre bought a little farm with a large garden. Here, while their father was buying ships in faraway harbours, the boys would spend weeks, sometimes months, with their stepmother.[2] Adolescence and introduction to literature At the age of seventeen Hendrik left his father's house to become a tutor in Antwerp and to continue his studies, which were soon interrupted by the Belgian Revolution of 1830.[2] He volunteered in the Belgian revolutionary army, served at Turnhout and fought the Dutch near Oostmalle, Geel, Lubbeek and Louvain. After the Ten Days' Campaign of 1831 he stayed in army barracks at Dendermonde, becoming a non-commissioned officer, rising to the rank of sergeant-major. In 1837 he left the service and returned to civilian life. Having been thrown in with young men of all walks of life he became an observer of their habits. He considered writing in the Dutch language although at the time that language was believed to be unfit for literature as French was the language of the educated and the ruling class.[citation needed] Although nearby, across the river Scheldt, the Netherlands had a thriving literature that was centuries old, written in a language hardly different from Dutch spoken in Belgium, the Belgian prejudice towards "Flemish" persisted. French was the language used by the politicians who founded Belgium in 1830. It was this language that had been chosen to be Belgium's national language. It was spoken by the ruling class in Belgium. Nothing had been written in Dutch for years when Belgium's independence became a fact in 1831, separating Belgium and her Flemish provinces from the Netherlands. The divide between the two languages was no more to be bridged. It was therefore almost with the foresight of a prophet that Conscience in 1830 wrote: "I do not know why but I find in the Flemish language indescribably romantic, mysterious, profound, energetic, even savage. If I ever gain the power to write, I shall throw myself head over ears into Flemish composition." Work and careerHis poems, however, written while he was a soldier, were all in French.[1] He received no pension when he was discharged, and returning to his father's house without a job, he made a conscious decision to write in Dutch.[1] A passage in Guicciardini fired his fancy, and straightaway he wrote a series of vignettes set during the Dutch Revolt, with the title In 't Wonderjaer (1837).[3] The work was self-published and cost nearly a year's salary to produce.[4] The Lion of Flanders His father thought it so vulgar of his son to write a book in Dutch that he evicted him, and the celebrated novelist of the future started for Antwerp, with a fortune which was strictly confined to two francs and a bundle of clothes. An old schoolfriend found him in a street and took him home. Soon people of standing, amongst them the painter Gustaf Wappers, showed interest in the unfortunate young man. Wappers even gave him a suit of clothes and eventually presented him to King Leopold I, who ordered the Wonderjaer to be added to the libraries of every Belgian school. But it was with Leopold's patronage that Conscience published his second book, Fantasy, in 1837. A small appointment in the provincial archives relieved him from the actual pressure of want, and, in 1838, he made his first great success with the historical novel De Leeuw van Vlaenderen (The Lion of Flanders), which still holds its place as one of his masterpieces,[3] the influence of which extended far beyond the literary sphere. Despite the commercial success of the book, its high printing costs meant that Conscience did not receive much money from its sales.[4] During the 19th century, many nationalist-minded writers, poets and artists in various European countries were turning characters from their countries' respective histories and myths into romantic icons of national pride. With The Lion of Flanders Conscience did this successfully with the character of Robert of Bethune, the eldest son of Guy de Dampierre, count of Flanders, crusader and, most importantly from Conscience's point of view, a prominent protagonist in a struggle to maintain the autonomy of Flanders against great odds. Historians have accused Conscience of historical inaccuracies, such as depicting his hero to have taken part in the Battle of the Golden Spurs which, in fact, he did not. It was also pointed out that in reality The Lion of Flanders did not speak Dutch. Neither did his father, the count of Flanders Guy de Dampierre. Yet Robert of Bethune, "The Lion of Flanders", is still presented as a symbol of Flemish pride and freedom, which is due to the romantic, albeit incorrect portrayal by Conscience. Conscience's portrayal also inspired De Vlaamse Leeuw ("The Flemish Lion"), the long-time unofficial anthem of Flemish nationalists and only recently recognised officially as the anthem of Flanders. Subsequent work The Lion of Flanders was followed by How to become a Painter (1843), What a Mother can Suffer (1843), Siska van Roosemael (1844), Lambrecht Hensmans (1847), Jacob van Artevelde (1849), and The Conscript (1850). During these years he lived a varied existence, for some thirteen months being a gardener in a country house, but eventually as secretary to the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. It was long before the sale of his books—greatly praised but seldom bought—made him financially independent to some extent. His ideas however, began to be generally accepted. At a congress in Ghent in 1841, the writings of Conscience were mentioned as the seed which was most likely to yield a crop of national literature. Accordingly, the patriotic party undertook to encourage their circulation, and each new contribution by Conscience was welcomed as an honor to Belgium.[3] In 1845 Conscience was made a Knight of the Order of Leopold. Writing in Dutch had ceased to be seen as vulgar. On the contrary, the language of the common man became almost fashionable and Flemish literature began to thrive.[3] In 1845 Conscience published a History of Belgium at the request of King Leopold I. He then returned to picturing Flemish home-life which would form the most valuable portion of his work. He was by now at the zenith of his genius, and Blind Rosa (1850), Rikketikketak (1851), The Poor Gentleman (1851), and The Miser (1853) rank among the most important of the long list of his novels. These had an instant effect upon more recent fiction, and Conscience had many imitators.[3] Contemporary receptionIn 1855, translations of his books began to appear in English, French, German, Czech and Italian which achieved considerable popularity outside Belgium.[4] By 1942, it was estimated that one German translation of Conscience's work The Poor Gentleman alone had sold over 400,000 copies since its translation.[5] The French writer, Alexandre Dumas, plagiarized Conscience's book, The Conscript, to produce a work of his own, profiting from the chaotic intellectual property laws of the time.[6] Numerous pirated translations also appeared.[6] Later life and deathIn 1867 the position of keeper of the Royal Belgian Museums was created and given to him at King Leopold's demand. From then on, he lived in the custodian's house of the Wiertz Museum, now adjacent to the European Parliament. He continued to produce novels with great regularity, his publications amounting to nearly eighty in number. He was by now the most eminent of Belgian writers. In Antwerp, his 70th birthday was celebrated with public festivities.[3] After a long illness, he died at his house in Brussels in 1883.[citation needed] His funeral was held nearby, at St Boniface's Church in Ixelles. He was buried at the Schoonselhof cemetery in Antwerp, his tomb a monument honoring the great writer. Critical receptionMost of Conscience's work can be considered as clearly within the Romanticist school of literature and they make extensive use of rhetorical soliloquies and sentiment.[6] Subsequent developments in literary understanding, particularly the realism movement which emerged in Conscience's lifetime, have meant that his work sometimes seems "outmoded and primitive" to modern readers.[7] His use of language has also been criticized. According to Theo Hermans, Conscience "was no linguistic virtuoso, his narratives are sentimental, his plots unreal and his moral judgments conservative to the point of being reactionary."[8] Hermans did, however, praise Conscience's ability to "draw the reader into a fictional world" and for his ability to evoke battles and natural scenes through description, as well as his use of changes in tempo to draw the reader's attention.[8] Honours

See alsoNotes

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Hendrik Conscience.

|

||||||||||||||||