|

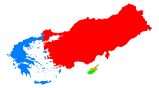

History of nationality in CyprusA de facto republic where Greek and Turkish Cypriots share many customs but maintain distinct identities based on religion, language, and close ties with their respective "motherlands", Cyprus is an island with a highly complex history of nationality due to its bi-communal nature and the ongoing conflict between the two groups. An internationally recognized region, Cyprus is partitioned into four main parts under effective control of the Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (recognized only by Turkey), the UN-controlled Green Line, and British bases Akrotiri and Dhekelia respectively. Despite its history of conflict, the Green Line is now open and neighborly relationships are being fostered between the two groups. Cypriot nationality prior to 1960Ancient ruleBeing strategically located between three continents, Cyprus is a unique nation that did not follow the pattern of current European territories, and until this day the island serves as a bone of contention between the rival nationalisms of the Greek and the Turkish.[1] Under the control of various powers throughout its ancient history, Cyprus was a Roman province from 58 BC to 395, after which it became part of the Byzantine Empire, then by Muslim Khalifate. Successively followed by periods of Lusignan (1192–1489), Venetian (1489–1571), and Ottoman rule (1571-1878), Great Britain eventually administered the region first under lease from the Sultan, and then upon annexation after the First World War with their colonial rule lasting until 1960.[1] SystemsPoliticsThe millet system established during the period of Ottoman rule was an administrative system that served as a means of effectively reinforcing the divide between Turkish and Greek Cypriots. An administrative structure which distinguished the communities based on religion and ethnicity, each group was treated as a distinct entity. With the Eastern Orthodox Church playing a dominant position among the Greek Cypriots so as to help them preserve their ethnic, cultural, and political identity, religious activities and institutions factored into virtually every facet of the Cypriot community. Through the imposition of taxation and other various administrative tasks on a denominational basis, the millet system served as a central contributor in the creation of "political cleavage over ethnic lines.[2] JudiciaryDuring the Ottoman period, a central supreme court in Nicosia was where the most significant criminal cases and appeals occurred. At the same time however, each district of the island (known as the five kaymakamliks) had their own separate systems in place which was presided over by the kaymakam, and represented both Muslim and Christian elected officials. The central court at Nicosia was similarly structured, but had more official clout in their supreme authority over legal matters across the island. Matters which fell under Islamic law such as marriage, divorce, or inheritance were controlled by the shari’a court.[3] British imperial ruleWhen the British arrived in Cyprus, they regarded the people they encountered as an entity that contained populations which spoke different languages and practiced different forms of worship. To the inhabitants themselves, however, the term "Cypriot" did not serve as an accurate definition of their identity.[4] The expansion of the Ottoman Empire had brought with it a fluid definition of the term, and one's socially relevant identity was thus defined based on their religious identification, with birthplace only becoming relevant in its capacity to establish social relationships. Thus the inhabitants of Cyprus regarded themselves as subjects, rather than citizens.[5] Legal system"The implementation in Cyprus of a European governmental rationality and categorization could not be contained within the forms of that rationality itself but instead overflowed those bounds and leaked into seeming unrelated areas of life."[6] Central to the ideologies of British colonial rule was the concept of equal application of legal-bureaucratic rationalization which would allow the colony to mature in a civilized, moral manner. Unfortunately, the British developmentalist approach was never effectively implemented, thereby serving as an indication of the strength of religious, familial, and cultural strongholds which governed the region.[7] However, after a few years under British rule, the island saw an explosion of crime. Believed by the colonial administration to have been the response to "a sudden transition to a comparatively liberal institution [being] let loose in the minds of people who have a tendency towards wickedness, and that taking advantage of the liberty [led them to] engage openly in crime", a direct link was perceived between the breakdown of traditional hierarchies and the breakdown of social order.[8] Following the establishment of a Legislative Council to deal with legal issues specific to Cyprus, it was decided that the Ottoman legal system that was in place when the British came in was regarded by the new administration as being too centralized. Claiming that the judges were prone to bribery and lacked legal training, a complete overhaul of the system was implemented in an attempt to correct the corruption of the old regime and restore a sense of order to the island.[3] A unified organization of the courts that administered a dual law system (British peoples subjected to English law and Ottoman subjects to Ottoman law), a supreme court of English judges to replace the 'corrupt' Muslim judges, as well replacing a large proportion of the Ottoman police force (known as the zaptiye), reflect the British response.[9] Religion and politicsThroughout its history, religion in Cyprus was highly political. Upon British arrival to Cyprus, it was Archbishop Sofronios who was forced to deal with the paradoxical situation in which the Church has been placed under the new administration. However, after having grown weary of the petty political intrigues that engulfed the latter years of his reign", Sofronios died in the spring of 1900, only for the factions that so exhausted him to strategize a means of coming into power.[10] It was thus in the wake of Sofronios' death that the church's struggle for power and their ultimately triumph over national politics was set into motion. Recognizing the need to regain the state support they had lost under British administration, the clergy needed to find a way to have their decisions enforced by the will of the people and regain authority within the state.[11] "The battle to elect an archbishop that ensued upon Sofronios' death began the first political campaign in Cyprus that might be called "modern." When the British came into control and the Church lost their political authority, they lost their funding as well. It was therefore in this climate of instability that the argument was made that the power of the Church and that the obligations of its people should be written into law, and that the only means of doing so would be to assign fixed salaries to the clerics, as this was believed to be a means of reconsolidating the power of the Church. The struggle for religious power under colonial rule reflects the continued desire of the Greek Orthodox Church to preserve the political stronghold they maintained during Ottoman rule.[11] Bi-communal character under British ruleBy the time the British took control of the island in 1878, the bi-communal character of Cyprus had become deeply engrained in the society. With the millet system not having been fully abolished upon the establishment of British rule, a modern bureaucratic system was implemented, however control over religion, education, culture, personal status, and communal institutions.[12] The divisive education systems were of particular significance in the upholding of ethnic distinctions between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots in the emphasis they placed on religion, national heritage, ethnic values, and the history of the Greek-Turkish conflict. The divisive curriculum combined with active church involvement in educational affairs contributed to the transference of conflicting ethnic values through the generations.[2] Education in nationalismIt was only in the aftermath of the Second World War that Greek nationalism in its Cypriot phase was able to claim popular support for violent revolt. Greek Cypriot educators and politicians believed there was a direct link between the transmission of nationalist ideology and the creation of young Greek nationalists. Turkish Cypriots in contrast, believed moral discipline of nationalism would come from self-improvement through "culture" and "enlightened education." The sociological foundation of Turkish nationalism thus appeared to imply that the best education was a cultural one that gave pride of place.[13] An education in nationalism in the context of Cypriot society was one oriented towards moral discipline which produces the habits of a patriotic life. To extend this concept to the nationalist violence which ensued in Cyprus, "it should be clear that the two sides of the conflict – namely, sacrifice and aggression – are irreducible to secondary explanations that describe war not as killing for one's country but dying for one's country." Perpetuating this notion of death as a patriotic act in educational institutions led to increased tensions between Turkish and Greek Cypriots.[13] Makarios' Petition 1950In 1950, Archbishop Makarios III of the Greek Cypriot Church initiated a petition which any inhabitant of Cyprus could sign which stated "we demand unification of Cyprus with Greece." Presenting their appeal to the UN General Assembly in 1950, it was believed that 'Cyprus belongs to the Greek world; Cyprus is Greece itself' The Greek government called for self-determination to assist in the unification.[14] However, despite 215,000 of the 224,000 inhabitants having expressed support for Greek union, there was no response from either Greece or Britain as they did not want to disrupt their bilateral relations.[15] Turkey in the meantime reacted to the Greek appeal to the UN by taking measures against the Greek community in Turkey. From confiscation of property to the expulsion of thousands of people, Turkey argued that Greece was pursuing a policy of using ethnic justification to conceal their territorial expansion policies.[15] Turkey thus proposed that Cyprus was very important to Turkish security and that the island should be put back into Turkish control as it had been for nearly four hundred years. While not in accordance with UN principles of self-determination, Greek and Turkish governments negotiated settlement under British directorship in 1959.[16] Proposals of Lord Radcliffe 1956By 1954, the state of affairs spurred military resistance from the Greek-Cypriot underground organization "EOKA." Proposing a resolution to condemn Greek support for this "terrorist organization", the Greek government issued a counter-proposal stating that the people of Cyprus should be granted the right to self-determination of their future. After having established the need for a peaceful solution in accordance with the principles and purposes of the UN, in 1956 Lord Radcliffe of Britain proposed that When the international and strategic situation permits...Her Majesty's Government will be ready to review the question of application of self-determination...to exercise of self-determination in such a mixed population must include partition among the eventual options[17] Macmillan Plan 1958In the spring of 1958, the Greek and British governments could not come to an agreement on a system of self-government, and thus presented the Macmillan Plan which stated that the United Kingdom, Greece, and Turkey would jointly administer Cyprus.[18] Ethnic conflict and political repercussionsAs a result of the bi-communal character that was established under the legislation of the late 1950s, Greece and Turkey both had long-lasting impacts on Cyprians national and ethnic identity. Despite four centuries of coexistence, the two communities maintained separate ethnic characters. Strongly divided over linguistic, ethnic, cultural and religious lines, the British colonial framework of 'divide and rule' reinforced the separation and made no attempts to unify Cypriot political culture.[19] Republic of CyprusIn the post independence period, it was not enough for Turkish Cypriots to be equal under the law; they wanted to be recognized as equal to their Greek compatriots. Claiming that their "nationalistic impulses", or desires for modernization and progress never found a voice, the Greek Cypriot demand for justice and respect ignored the similar demands of Turkish Cypriots. "It is within this context that one must interpret the growing demand among Turkish Cypriots for something they called "culture" that was supposed to improve the community and lead them into a brighter future."[20] Establishment of the RepublicGiving way to the various pressures such as the Greek Cypriot anti-colonial revolt, international pressures, as well as problems within NATO which posed great challenges and financial burdens for British authorities, Britain granted Cyprus its independence in 1960. With the end of British colonial rule, Cyprus found itself in the middle of ethnic-motivated policies made by two rival nations. Given that the goals and values of these two countries were shared by their respective communities on the island, the creation of an independent Cypriot state "represented the narrow-middle ground between mutually exclusive ethnic policies and goals."[21] Zurich and London agreements 1959After a diplomatic attempt to convene a multilateral Cyprus conference failed as a result of Greek resistance, in December 1958 Greek and Turkish foreign ministers entered into bilateral negotiations.[22] Convening in Zurich in 1959 to establish the foundation for the political structure of the new state, the treatises and the constitution were officially signed on 16 August 1960 in Nicosia.[23] The treatises were:[23]

Constitution of the Basic structure of the Republic of CyprusBased on the dualism of the Cypriot community, the constitution accounted for the bi-communal nature of the state through the regulation and protection of the interests of both communities as distinct ethnic groups. The right for Turks and Greeks to celebrate their respective holidays, the foundation of respective relations with Greece and Turkey on educational, religious, and cultural matters, and the transplantation of ethnic fragmentation into the justice system, serve as examples of the dualism in government being implemented on a social level.[24] However, the major instruments used for preserving cross-boundary ethnic bonds extend far further than national symbols. Rather, education, religion, culture, language, history, and military ties were implemented as a means of enhancing the division between the two groups, while at the same time strengthening the bonds with their respective motherlands.[25] ProblemsUnfortunately, the stipulations of the constitution were rigid to the point of being unworkable on a practical level. Referred to as "a constitutional straight-jacket [sic?] precluding that adaptation essential to the growth and survival of any body politic", the preservation and reinforcement of ethnic and political cleavages as was reinforced through the constitution had a detrimental impact on the new republic.[26] Furthermore, extensive minority safeguards were implemented as a compromise of the drafters and served as a reflection of the inherent inequality in Turkey's superior negotiating power, leaving many Greek Cypriots discontent with various constitutional provisions which they deemed unjust and unrealistic. Various incidents centered on basic articles of the constitution had the effect of undermining the entire state-building process.[26] Ethnic and social fragmentation"It was on these fragmented historical and social foundations that an independent bi-communal Cypriot state was built in 1960."[27] Serving as a representation of the divided past between the two groups, the institutional framework of the Republic of Cyprus treated Turkish and Greek Cypriots as distinct political units which enhanced ethnic fragmentation and political division in the new republic. The historic inheritance of ethnopolitical polarization, combined with a lack of experience in self-governing and consent in political leadership over means of consolidating ethnic conflict therefore served as significant factors in the collapse of the Cypriot state in 1963.[27] "The legal controversies and political polarization which paralyzed the state and the political process was merely a 'superstructure' of a similarly ethnically polarized and potentially explosive 'infrastructure' inherited from the past." With social segregation reinforced through means of division such as the absence of intermarriage, as well as limited participation in joint cultural events, there was minimal common ground upon which social interaction between the two groups could be established. Extending further into the workforce, the preservation of the segregation of education systems implemented in the colonial era, as well as separate newspapers, the two groups were unable to reconcile their traditional conflicting ethnopolitical agendas of enosis and taksim.[28] BreakdownWith constitutional crises, political immobilization, ethnic passion, limited bi-communal interaction and underground military groups emerging in the highly unstable climate of the Republic of Cyprus, "the political and psychological setting was ripe for an open confrontation." With the spark of conflict ignited by factors such as President Makarios' Thirteen-Point proposal, and the Nicosia incident, after three years of ongoing tension between Turkish and Greek Cypriots and with fruitless efforts to reconcile their broad spectrum of grievances, "a complete constitutional breakdown and eruption of violence occurred in December 1963."[29] Despite various attempts made by the Guarantor powers to restore peace and order in the region through measures such as the Green Line and the failure of the international conference, British and Cypriot governments brought the issue to the UN Security Council on 14 February 1964. Recommending the creation of a United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP ) to restore law and order, even the adoption of this UN resolution did not prevent further fighting.[30] 1963 crisisTurkey's intervention into Cyprus' constitutional and ethnopolitical crisis marked an important beginning to a new phase of internationalization of the problem. Greece responding by coming in to defend Greek Cypriots, external intervention amplified the already tense climate of communal violence. With Greek and Turkish contingents already stationed on the island joining in the fighting. Britain proposed the establishment of a joint peacekeeping force, but while all the parties involved agreed to the proposal, since Greek and Turkish troops were already involved in the confrontation and thus peacekeeping was eliminated as an option for these groups. Mobilizing troops, warships and aircraft Turkey and Greece threatened to invade one another, and "the danger of an all-out Greek-Turkish war became a real and imminent possibility", particularly upon Turkey's decision to invade Cyprus in June 1964.[31] [[See Turkish invasion of Cyprus]] "Throughout the repeated crisis that developed on Cyprus since 1963, Greece and Turkey acted as uncompromising rivals rather than members of the same political-military alliance." Their confrontation and the dangers involved were manifested in the military as well as the diplomatic fronts, and are to be regarded as a culmination of gradually increasing Greek and Turkish involvement in Cyprus, and the "renewal of old ethnic animosities." With ethnic affiliations and treaty provisions providing channels for Greek and Turkish participation in the conflict, external involvement made the crisis increasingly difficult to resolve.[32] Turkish intervention and continued presenceCoup d'etat against President MakariosIn 1967, a military junta took power in Athens. A couple years later in 1971, the leader of the EOKA, Grivas, founded the EOKA-B, thereby openly undermining President Makarios' authority, and handing off command of the EOKA-B to the General Staff of the Greek military junta and its collaborators on the island of Cyprus in 1974.[33] After declaring the EOKA-B to be illegal and demanding Greek President Gizikes to withdraw Greek officers from the Cyprus National guard from the island, the Greek dictator ordered the coup against Makarios on 15 July 1974.[33] Please See Cyprus or Makarios III for further information The bloody coup which the Greek junta staged against the Cypriot President upset the delicate balance of power on the island. Fleeing the Island with British assistance after the Greek-led Cyprus National Guard occupied the Presidential palace; Turkey invaded Cyprus so as to seek protection for Turkish Cypriots.[34] While the immediate repercussions the coup had on Turkish Cypriots is subject to debate, it was following the Greek overthrow that Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974. Perceived by the Greeks as an expansionist plan against Cyprus and Hellenism, "the overwhelming majority of Greeks believed that Turkey was a threat to Greece's national security and territorial integrity." In reality however, despite various grievances between the Turkish and Greeks, the Turkish invasion of the island was prompted by the Greek coup in Cyprus, and not by the domestic strife between the two communities.[35] "Despite the intercommunal friction and sporadic fighting and violence in the island which brought Greece and Turkey close to war in the island in 1964 and 1967, Cyprus continued to be united and independent. However, both Greece and Turkey were extensively and belligerently involved in Cyprus communal and constitutional affairs."[36] With Greece actively pursuing enosis and Turkey seeking taksim, the division between the two communities on the island had become a de facto situation and an indisputable reality.[37] Legality of the conflict in 1974The Turkish occupation of Cyprus in 1974 resulted in the division and de facto partition of the Republic of Cyprus and the creation of the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in the Turkish-controlled areas of Cyprus. Destroying the state of affairs the Treaty of Guarantee and articles of the UN charter which were designed to protect and serve, the Turkish invasion and continued occupation of nearly 40 percent of Cypriot territory is a violation of international law.[38] Negotiations and proposals since 1974Despite the calls from the international community, Turkey has failed to withdraw its military forces from the Republic of Cyprus and to end its military occupation. The international legitimacy of Cyprus thus has not been restored on account of Turkey's lack of cooperation. In order for the issue to be resolved, Turkey must finally comply with international law. However, a second dimension to the Cyprus Problem is to achieve a "lasting and effective legal solution of the intercommunity relationship and peaceful coexistence between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus."[39] In the event of withdrawal from Cyprus, Turkey is greatly concerned over the welfare of Turkish Cypriots. On the other hand, Greece and Greek Cypriots fear the eruption of hostilities if they were to withdraw. "Additionally, the Turkish military withdrawal from Cyprus would greatly restore Greece's national honour and pride with respect to the tragedy of 1974."[40] Building a nation in Cyprus by the Greek and Turkish-Cypriots poses quite a challenge to the international community. The new trend in world affairs had been towards the disintegration of the traditional concept of nation-states with creation of new ethnic and tribal identities through secession from their nation-states. An intensification of Greek-Cypriot efforts to become full members of the UN is deemed necessary, as efforts to unite Cyprus as a new federation with Turkish Cypriots may be unreasonable.[41] NATOBefore joining the alliance in 1952, Greece and Turkey had been regarded by NATO as difficult but important countries. Originally left out because they were not Atlantic combined with their economic and political problems making them more of a burden than an asset, Greek and Turkish membership did in fact pose serious problems to the Western alliance. "Early warnings about the potential dangers of Greek-Turkish rivalry over the independent Cyprus prompted NATO officials to intervene and seek a solution to the colonial problem that would eliminate the sources of ethnic conflict." NATO therefore proposed measures such as the implementation of bases, Cypriot membership into NATO, making the island a NATO-trust territory; however, the internationalization of the Cypriot problem through the UN undermined NATO initiatives. The alliance was pleased by the creation of the Republic of Cyprus, but their optimism was short-lived when conflict struck again in 1963.[42] NATO's response to the 1963 crisisFor the first time in NATO history, troops from two member states were fighting one another. Besides their involvement in hostilities on Cypriot soil however, Greece and Turkey worried NATO in their mobilization and massing of troops. As a direct consequence of their involvement in the crisis, and particularly because of their decision to sail navies into Cyprus, Greece and Turkey significantly weakened NATO's southern flank. According to American diplomat George Ball, "the ethnic conflict in Cyprus threatened the stability of one flank of our NATO defences and consequently concerned all NATO partners."[43] NATO Peace PlanThe main provisions of the NATO plan were the following;

Since all NATO members had an interest in stopping the intercommunal violence in Cyprus, for if the conflict was allowed to develop it would lead to a clash between NATO allies. Thus serving as a reflection of the fears that the Western capitals feared the conflict would pose, the plan set to resolve the problem through intervention and playing an active role in peacekeeping and mediating. Implemented with the purpose of establishing a NATO grip on the island and eliminating the conflict, "it was with this purpose in mind that the Greek and Turkish contingents would be absorbed by the NATO force and the two mainlands would waive their rights of joint or unilateral intervention."[44] FailureUnfortunately, the prospects of NATO's peace operation being successful were slim from the beginning. The following factors hindered the constructive interference of the Western alliance.

The unsuccessful NATO initiative on Cyprus was the first and last attempt by a regional military regime to interfere in ethnic conflict. Consequently, NATO played a minimal role when conflict broke out once again in 1974. However, their lack of involvement may also be attributed to UN involvement.[46] Role of the United NationsUN involvement in the Cyprus issue prior to 1974Although the Cyprus issue was brought to the attention of the UN in the 1950s, despite President Makarios' numerous attempts aimed at the internationalization of the issue so as to place global pressure on Britain to withdraw from the region, it was only after the eruption of inter-communal violence in 1963 that the UN became involved.[47] Shifting the attention of the Security Council to the restoration of the internal security of Cyprujs, Maakarios was successful in[clarification needed] having the organization take up the issue. Several discussions were held between 1968 and 1974, and were close to finalizing details of an agreement when the coup d'état against President Makarios occurred. It was thus only in 1964 with the formation of the UNFICYP was formed that signs of UN involvement were made most visible.bill[48] Vienna negotiationsFollowing five rounds of the negotiations at Vienna in 1975, it was established under the so-called Vienna III agreement that Turkish Cypriots could settle in the North, with efforts put in place to ensure the freedom and right to live a normal life being extended to Greek Cypriots already living in the region. Ultimately however, the agreement was not properly implemented. In the final round of negotiations, the positions of Turkish and Greek Cypriots proved irreconcilable and a meeting proposed to discuss their proposals was never arranged.[49] Further negotiationsThe Makarios-Denktas High Level Agreement of 1977, the Kyprianou-Denktas High Level Agreement of 1979, The 1983 Memoire of Perez de Cuéllar, as well as a variety of efforts between 1984 until the present have been implemented in an attempt to reconcile the grievances between the two groups. However, due to Turkey's unwillingness to compromise combined with certain agreements falling short of international law, and consequently none of the resolutions are legally binding.[50] Conceptually, the UN's task is to reconcile the Greek Cypriot attempt to return as close as possible to the status quo (before 1974), versus the Turkish Cypriot objective to legalize the de facto situation which has been in place since then. In an attempt to bridge these aspirations, the UN proposals embody the core issues of governance, territory, property and security.[50] Current status of the Cyprus problem in the UN"Despite the continued tensions and dangers of a war conflict caused by the Cyprus problem, the United Nations, and generally the international community, has failed to play an effective and dynamic role in the solution of the Cyprus problem. It appears that the Cyprus problem and its solution have not been treated as a high enough priority on the United Nations global agenda." While the UNFICYP continues to strive towards a solution, the situation is generally regarded as an old and contained conflict, and the Turkish invasion has become a status quo problem.[51] UNFICYPThe United Nations Peace-keeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) was established with the consent of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus on 27 March 1964. Mandated following the outbreak of intercommunal violence and Turkey's imminent invasion, the force was initially stationed for three months but was later extended and renewed in the interest of preserving peace and security. MandateAccording to the mandate laid down in Security Council resolution 186 (1964) and subsequent resolutions of the Council concerning Cyprus, UNFICYP's main functions in the interest of preserving international peace and security, can be summarized as follows:

European UnionIn 1962, one year after the British applied for membership, Cyprus asked the European Community for an institutionalized arrangement given their heavy dependence on British exports and the prospect of losing the preferential tariff rate. However, after the British withdrew their application, Cyprus's interest remained dormant until 1972 when the British admission into the community was certain. The agreement was delayed due to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, as it had disastrous effects on the Cypriot economy. The agreement was finally signed in 1987.[53] What is important to note about Cyprus' application for membership is that it was made on behalf of the entire population of the island. Turkish Cypriots challenged the application, but the community rejected their argument, as the EU followed suit with the UN in refusing to recognize the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. It was only after the Commission opinion of June 1993 that Turkish Cypriot authorities decided to cooperate.[54] Cyprus' accession to the EU was particularly desirable due to its geographic location, as its position as Europe's last outpost in the eastern Mediterranean is of significance for symbolic and security interests. Cyprus' links to the Middle East are also of significance to the EU, as it serves as a cultural, political, and economic link to this significant geopolitical region. Furthermore, Cyprus is headquarters to many multinational firms. It is thus its location, accessibility to educated managerial and technical staff, combines with its excellent transportation, communication, and legal networks that serve an asset to the EU.[55] Cyprus QuestionThe EU is a firm supporter of UN efforts to achieve peaceful settlement of the region, and at its meeting in Dublin in June 1990 they issued a declaration stating 'the European Council, concerned about the situation, fully affirms its support for the unity, independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Cyprus in accordance with relevant UN resolutions.' The EU also decided to appoint a representative to monitor developments of the Cyprus peace process. Due to their concern over lack of settlement of the region, the EU is considered to be in a unique position in playing a role to bring about stability to Cyprus. Becoming part of the EU integration process offers Greek and Turkish Cypriots an opportunity to resolve their differences and achieve the security and stability they have been longing for.[56] Current state of affairsThe omnipresent notion of nationalism in the form of identity politics and the claims of culture is reflected in the conflicting nationalisms of Cyprus. The bi-communal nature of the territory and the ongoing tensions between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities has played a profound role in the shaping of national identity, resulting in ones sense of nationality being tied more to culture and loyalty to members of their community as opposed to the island of Cyprus itself. The duality of their legislative system and the far-reaching consequences of the conflict between Greece and Turkey which extend into virtually every facet of Cyprus society serve as further indication of the complexity in establishing a concrete and unified definition of nationality in Cyprus.[57]

Citizenship LawAccording to Article 14 of the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus Law of 1967; The Republic of Cyprus Citizenship Law of 1967 makes provision for the acquisition and renunciation and deprivation of citizenship, and states that "no citizen shall be banished or excluded from the Republic under any circumstances". Cyprus passportsAll Cypriot citizens are eligible for a Cypriot passport.

See alsoNotes

Further reading

External links

|