|

Hog Island (Wisconsin)

Hog Island is an uninhabited island located off the eastern shore of Washington Island in the town of Washington, Door County, Wisconsin, United States.[1] The island has a land area of 2.14 acres (8,656 m2)[2] and an elevation of 10 feet[3] or 20 feet[4] above Lake Michigan. HistoryNative AmericanIn 1917, historian Hjalmar Holand recorded "indications of an aboriginal village site" at Sand Bay, on the shore directly opposite of Hog Island. This area had a half-mile of sandy beach, the only such beach on the east side of Washington Island. Holand cautioned that the extent of the village was still unknown.[5] In 2012, United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) staff noted that no cultural resources survey to look for artifacts had been made on Hog Island.[6] ShipwreckOn August 7, 1871, while bound from Menominee, Michigan, for Chicago with a cargo of lumber, the General Winfield Scott encountered heavy seas off Spider Island and capsized without loss of life. Her capsized hull floated north until she ran aground on the shoal extending between Hog Island and Washington Island.[7][8] Items worth salvaging were taken by residents of Washington Island, but remains from the shipwreck are visible today[9] in the shallow water about 7 feet (2.1 m) deep.[7] Bird reservationIn 1908, A. C. Burrill of the State Entomologist's Office in Madison, Wisconsin, publicly advocated the creation of reservations for gulls or other birds in Wisconsin. He was able to interest many people, but his efforts failed.[10] In 1911, Charles E. Pidgeon surveyed the island for the United States General Land Office. He wrote a summary:[3]

Charles E. Pidgeon's plat of the island

In 1912, Frank Bond, the chief of the Drafting Division[11] of the General Land Office was responsible for getting Hog Island protected as the Green Bay Reservation in Executive Order 1487 by President William H. Taft in 1912 as the Green Bay Reserve. The island was the only one in the reserve. Bond's clerk position entailed locating and recommending action on all bird reservations and also preparing executive orders for the President's signature. He was a life-long bird lover and was also a member of the American Ornithologists' Union and his local Audubon Society.[12] Prior to service in the General Land Office he had been a director of the National Association of Audubon Societies.[11] At the time, few people in Wisconsin knew about Bond's work or the creation of the reserve.[10] The basis for creating the reservation and also three other new federal bird reserves during the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1912, included an ornithologists' report published in the 1890s on birds beneficial to agriculture. The list included game birds, insectivorous birds, and birds of prey. The report showed that the populations of beneficial birds altogether had declined over the previous 25 years.[13] In 1912 there were 56 federal bird reserves, which were all created by executive orders following the recommendation of the Department of the Interior to the President. They were "regarded as in all essential particulars reservations of public lands for public use or other purposes" and were created under the authority of the 1906 law introduced by John F. Lacey, which followed his earlier Lacey Act of 1900. The 1906 act forbade anyone to kill birds, take eggs, or to "willfully disturb" birds upon the reservations, "except under such rules and regulations as the Secretary of Agriculture may from time to time prescribe". The reservations were administered under the direction of the Bureau of Biological Survey of the Department of Agriculture.[14] Another similar effort similar to the 1908 attempt was made in the autumn of 1912 by Dean H. L. Russell and C. R. Van Hise, the chairman of the Conservation Commission of Wisconsin. Their effort focused on locating and protecting the breeding grounds of the American herring gull. They gathered signatures and affidavits from Door County landowners near gull nesting areas, using federal forms provided by the United States General Land Office. The Conservation Commission forwarded their paperwork along with its own urging to the U.S. Biological Survey officials. Their efforts secured Executive Order 1678 on January 9, 1913,[15] which set aside Spider Island and Gravel Island as the Gravel Island Reserve.

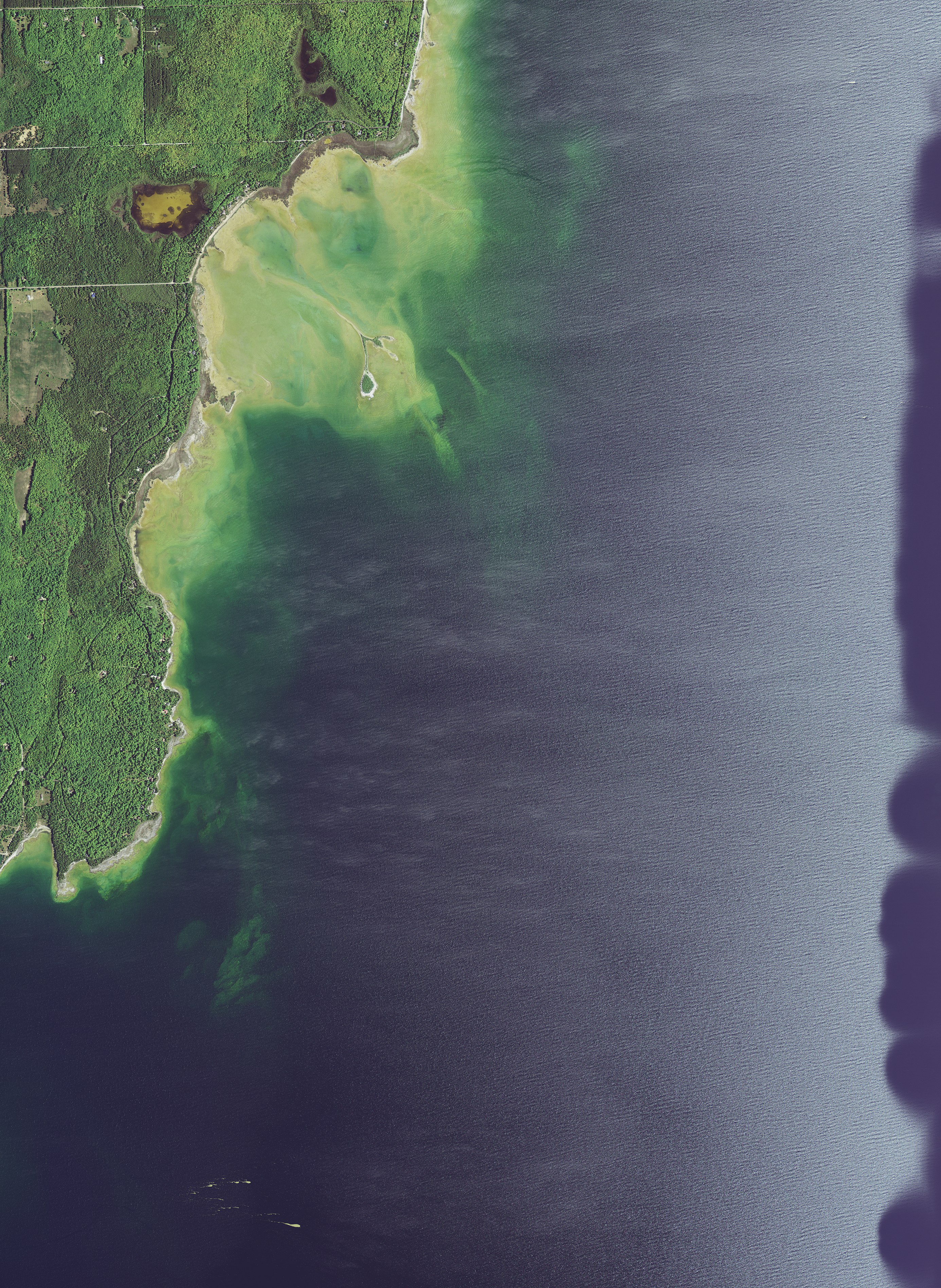

Hog Island on June 5, 1938; the average lake level for June 1938 was 176.28 meters above sea level.[16]

The intention for the islands was that they would eventually become nesting areas for Caspian terns, shore birds, and herons in addition to gulls. Another purpose of the reserves was to please the many bird-lovers in the state and to aid farmers, since these birds eat insect pests and rodents. An additional purpose was to improve the human public health of the lake and shore communities where the birds would act as beneficial scavengers.[10] Additional efforts in favor of the reservation were made by T. S. Palmer of the U.S. Biological Survey and by people in a variety of Wisconsin communities who recorded bird observations in 1912.[17] In 1926, volunteers William I. Lyon of Waukegan, Illinois, George Lyon, and Clark Miller banded birds at Hog Island and other islands in the county. They recorded data and sent it to the U.S. Biological Survey.[18] In 1930, volunteers William I. Lyon and Clark Miller of Racine visited "the many small islands surrounding Washington island" and altogether banded around 1,000 gulls and Caspian terns. The two men were part of a large bird banding project coordinated by the U.S. Biological Survey involving 1,800 people. Birds on islands along the peninsula were banded by Ephraim residents.[19] Wildlife refugeIn 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt changed the name to Green Bay National Wildlife Refuge by issuing Proclamation 2416. The proclamation renamed federal bird reservations in order to easily distinguish them from state-owned and managed bird reserves.[20]  Wilderness areaCounty hearingOn February 15, 1967, a hearing on a proposed Wisconsin Islands Wilderness concerning Hog, Spider, and Gravel islands was held at the Door County courthouse.[21] It was noted that prior visitation to the three islands had been limited to a few bird enthusiasts who expected the repulsive smells and discomforts associated with nesting colonies of gulls and herons. It was proposed that "Public access would need to be prudently limited in numbers and restricted to late summer and early fall when Lake Michigan travel is often difficult."[22] No one was opposed to the proposal.[21] Department of the Interior recommendationOn March 13, 1968, Stewart Udall, the Secretary of the Department of the Interior recommended the addition of the Wisconsin Islands Wilderness along with the Michigan Islands Wilderness to the National Wilderness Preservation System to President Lyndon B. Johnson, noting of the islands in both proposed wilderness areas:[23]

Initial billOn May 7, 1968, Congressman John W. Byrnes introduced a bill in the United States House of Representatives to designate the three islands as the Wisconsin Islands Wilderness. He justified his intentions on the basis that the islands "are extremely important nesting and resting grounds for thousands of native birds, and while seldom visited because of difficult accessibility and landing conditions, they offer a unique wilderness opportunity to the serious student of nature."[24] Senate hearingIn 1969, Senator Gaylord Nelson and three other senators introduced Senate Bill 826, which included the Wisconsin Islands Wilderness proposed earlier in the House by Byrnes.[25] Following the introduction of the bill, the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs held a hearing concerning the proposed wilderness designation, which was filmed and shown by a Green Bay television station. A total of 27 people were present at the hearing, with statements presented by eight as individuals and seven who represented organizations. All 15 statements favored the proposal. Communications about the proposal were submitted by 159 individual citizens, and all were in favor of the proposal. The main argument submitted was that wilderness status would protect the islands from undesirable developments. Following the hearing, an additional 32 individuals submitted communications, and all also in favor of designating the islands as wilderness. The main argument from 17 total organizations, all of which supported the proposal, was that wilderness status would preserve the islands in their existing state. In addition, a county supervisor commended the past protection given to the islands, and also supported the proposal. The Wisconsin State Conservation Department likewise submitted a favorable statement concerning the proposal.[26] The synopsis of the Senate hearing noted that "Some of the tree and shrub cover of the islands has been lost due to avian life such as the great blue and black-crowned night herons." The report noted that nesting conditions on the island were especially ideal during low water conditions, which created additional habitat. It concluded that:[26]

The bill passed the Senate without dissenting votes[25] on May 26, 1969.[27] House hearingSubsequently, a hearing was held before several subcommittees of the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs.[28][27] Nelson repeated statements used earlier by Udall in his letter, and urged that the areas be "forever protected from the intrusions of man".[25] Congressman Robert Kastenmeier, who had introduced House Resolution 4275 as an identical measure to Senate Bill 826 in the House,[25] also attended this hearing. He also repeated the same statements used by Udall, and added that "the lands are all Federally owned and no cost will be incurred by designating them as wilderness. It is to secure the perpetuation of these treasured areas that I urge favorable support of this legislation."[29] He also cited in support that "A hearing on the Wisconsin islands wilderness proposal at Sturgeon Bay, Wis., in 1967 produced unanimous support from local and State conservation groups, as well as a favorable statement from the State of Wisconsin."[30] Byrnes noted that the islands were "seldom visited except by dedicated bird enthusiasts"[31] and pointed out that earlier the three islands had only been protected by executive orders rather than by legislation. He advised that "Such legislation will secure additional, statutory protection for these islands, which are valuable only because they have been kept wild and undisturbed, and because they remain so to this day."[31] In addition, he knew of no opposition to the proposal in his congressional district.[32] During the hearing, Congressman Sam Steiger challenged John S. Gottschalk, the director of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife over how the islands would be managed. Gottschalk noted that the islands were "primarily valuable from the standpoint of nesting habitat which they provide for Colonial birds"[33] but "are virtually inaccessible because of the shallow water surrounding them. It is hazardous, and sticky to get out to these islands and very few people do have a chance to get out to these islands."[33] When Steiger asked about staffing, he replied that, designated as wilderness, the islands would require less personnel for staffing than otherwise.[34] Steiger responded,[35]

Gottschalk replied,[35]

Steiger responded,[35]

Gottschalk replied,[35]

Steiger replied,[35]

Gottschalk responded with a "Yes".[35] Steiger asked,[35]

Gottschalk admitted,[35]

The National Wildlife Federation and its state affiliate endorsed the proposed wilderness designation on the basis of the islands' "values to waterfowl, herring gulls, and ring-billed gulls. Travel to the islands is difficult and visitor use is limited to special permittees for scientific and educational purposes."[37] PassageThe content concerning the Wisconsin Islands Wilderness was incorporated into subsequent legislation and eventually became part of the 1970 Omnibus Wilderness Act, which passed the House with a 91-504 vote.[38] The Act was signed by President Richard Nixon on October 23, 1970,[39] designating the three islands as the Wisconsin Islands Wilderness.[40] La Salle: Expedition IIOn November 4, 1976, 23 members participating in the La Salle: Expedition II reenactment took off from East Side Park along Jackson Harbor on Washington Island at 5:30 am. Their plan was to go around Washington Island and reach Gislason beach,[41] and then later on cross the Porte des Mortes passage to the Door Peninsula.[42] They encountered six-to-eight-foot (1.8 to 2.4 m) high waves and gale force winds. Two of the simulated birch bark canoes used by the expedition party capsized.[43] One of these canoes carried four young men from Streamwood and Elgin in Illinois. They were thrown into the water and when their canoe hit a shoal about a half-mile from Hog Island, capsized, and smashed. Survival time in the 39 °F water was estimated at ten to fifteen minutes. They tried to push the damaged canoe through the water in the rough conditions, but eventually gave up. They removed their sleeping bags and sent the canoe off in a direction where they hoped it would not get crushed when they reached the shore and swam to Hog Island, having spent about ten minutes in the water. As soon as they reach the island, they removed their clothes and got into the sleeping bags. An airplane flying overhead with a television crew spotted a submerged canoe floating in the water, but no bodies.[43] A second canoe with four crew members from Chicago, Rolling Meadows, and Streamwood was hit from the side by a large wave, causing it to begin to sink. Flotation equipment and an equipment bag in the canoe gave it some buoyancy, so it was only submerged six inches (150 mm) under the water line. The crew members paddled it to Hog Island.[43] Reid Lewis, who portrayed La Salle and was leading the reenactment became nervous and attempted to reach Hog Island from Washington Island in a motor boat, but was unable to due to the shallow water. Instead he sent one of their canoes, and a crewmember went through the brush on the island to find the four young men, who were still in their sleeping bags. He immediately built a fire for them. A Washington Island resident predicted the damaged canoe would wash ashore in a small, shallow cove no wider than 30 feet (9.1 m). Crewmembers waded in and got the canoe, which was sent to Chicago for repairs. It was back in service 48 hours later.[43] Washington Islanders told them that the only time the waters would be calm would be if the wind changed, which would give them about 20 minutes of calm water conditions. They waited on Washington Island for seven days, and especially for the end of the northwesterly wind, which lasted four days.[43] An hour after the wind subsided and began shifting around to the southwest, all five canoes made it across the Porte des Mortes to the Door Peninsula.[44] The following summer, Gary Heintz of Laurel, Maryland, went to Door County for research work. His wife Patricia was about 100 yards (91 m) east of Hog Island when she found in the water a rotted canvas bag, a small leather pouch with leaves and five coins, a cup, a large skillet, a Dutch oven with its lid, and another pot. Most of the pots were quite rusty, with the exception of the stainless steel cup. She sent a letter to Reid Lewis on September 18, 1977, who thought it was amazing she figured out that the gear was from the expedition.[43] State park proposal

Taken November 1, 1978; the average lake level for November 1978 was 176.62 meters above sea level.[16]

In 1978, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) proposed including Hog Island, six other islands, and one shoal for inclusion in a new Grand Traverse Islands State Park.[45] The DNR thought that Hog Island could both be included in the new state park and remain under United States Fish and Wildlife Service ownership.[46] An informational meeting was held at the Door County Courthouse on March 9, 1978. The department intended that Hog Island would be preserved in a near wilderness state. Some present were concerned about intended recreational development. The department planned to forbid camping on Hog Island and that "public access would not be encouraged" on Hog and other islands intended as wildlife refuges. There were no active measures to preserve shipwrecks lying in the waters surrounding the islands.[45] One concern expressed by citizens was the large amount of traffic from automobiles and boats which would be brought into the county as a result of the proposed park.[45] Likewise, a group commander for the United States Coast Guard reviewed the proposal and expressed concerns that the creation of the park would increase the Coast Guard's workload as boating activity increased in the area. He noted that "rapidly changing weather conditions and many shoal areas make boating extremely hazardous" in the area of the proposed park.[47] The DNR noted that presently "human use is extremely limited" on Hog Island.[48] An alternative considered by the department was for Hog Island to remain a National Wildlife Refuge. The department noted that in this case, "prohibited access would help protect the nesting bird colonies from disturbance".[49] The director of the Eastern States Office of the Bureau of Land Management questioned whether islands with very high wildlife values ought to be included in the park. He thought this would encourage visitor use and asked whether some other type of management was more suitable.[50] Plants and animalsThe vegetation on the island is low and bushy. In 1999, the plants on the island mostly consisted of red-berried elder, red raspberry, and other weedy shrubs. There were a few remnant balsam firs and some Canada yew. In the 1970s the island also had white cedar, white birch, aspen, and the shrub red-osier dogwood.[51] Because Hog Island contains two state-listed sensitive plant species, Western fescue and elk sedge, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service prior to 2016 destroyed nests and eggs of double-crested cormorants on the island. By doing so, they prevented cormorant chicks from hatching on the island. The service controlled cormorants on the island because their nests and excrement kills plants.[52] Another reason the service prevented cormorants from raising young on the island was to preserve the remaining woody vegetation.[4] Following a 2016 court judgement from a lawsuit filed by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, the service stopped issuing cormorant depredation permits for Hog Island, which allowed for successful cormorant nesting on Hog Island in 2016 and 2017. As of 2018, the service planned to continue non-lethal cormorant management on Hog Island and to monitor the impacts of the non-lethal tactics on cormorants and non-target species.[53] Hog Island supports a nesting colony of herring gulls, which nest around the edges of the island on open areas. Great blue herons, black-crowned night-herons, and great egrets nest in trees on the island interior, and red-breasted merganser nests can be found hidden in the dolomite ledges. Sandbar willows (Salix exigua) on the gravel spit provide cover for nesting waterfowl like mallards, black ducks, and Canada geese.[4] The solid dolomite base of the island discourages burrowing predators from taking up residence. For birds the island is a refuge from predation by mammals.[22] The island is managed by staff who must travel from the much larger refuge at Horicon Marsh. There is concern that visits by staff may cause nesting failure. This can happen in multiple ways: If the staff visit prior to nesting time or while the birds are building nests, they might decide to abandon the island for current and also future years. If staff visit before the eggs hatch or while the chicks are in the nest, the parents may fly away for awhile. While the parents are away from the nest, gulls and other opportunistic predators may eat the eggs and chicks. In addition, without parents to provide shade the nests may be exposed to direct sunlight, which can kill chicks or eggs in a matter of minutes if the day is hot enough.[54] Over the three years, from 2012 to 2015, the island was visited on seven different days. Two of the days were spent addling cormorant eggs with oil and destroying nests, and the other five days involved no killing or nest destruction.[54] GeographyDolomite ledges, which form broad steps around three-fourths of the island are barren and wave-washed. The remaining quarter of the shoreline has slopes that are covered with vegetation. The interior of the island is densely grown up with shrubs and trees. A long gravel spit on the northwest corner of the island protrudes northwestward, branching out at the tip.[4] Hog Island lies 0.6 miles (0.97 km) east of Washington Island.[55] Hog Island is located midway on a shoal which extends from Washington Island for one and a quarter miles (2 kilometres). The shoal is up to 12 or 13 feet (3.7 or 4.0 metres) deep at the outer edge.[56] The surrounding shoals and the lack of protected areas or docking facilities on the island make boat landing difficult.[57] The small size and low elevation of the island makes it susceptible to lake level changes. The area of the island and the plant and animal communities it supports fluctuate with the lake level.[58] Lower lake levels are concerning to the USFWS because Hog Island could end up connected to Washington Island, even temporarily. If the reef connects the two islands there is a greater risk of predators accessing Hog Island or people walking over and disturbing the nesting bird colonies.[59]

Water levels are from the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory.[16] Climate

Diagram of the island See also

References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![Hog Island on June 5, 1938; the average lake level for June 1938 was 176.28 meters above sea level.[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Eastern_and_central_Washington_Island%2C_Wisconsin_June_5%2C_1938.tiff/lossy-page1-1354px-Eastern_and_central_Washington_Island%2C_Wisconsin_June_5%2C_1938.tiff.jpg)

![Taken November 1, 1978; the average lake level for November 1978 was 176.62 meters above sea level.[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8a/Washington_Island%2C_Wisconsin%2C_aerial_November_1%2C_1978.jpg/4209px-Washington_Island%2C_Wisconsin%2C_aerial_November_1%2C_1978.jpg)