|

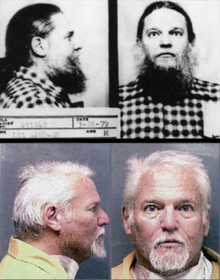

Ira Einhorn

Ira Samuel Einhorn (May 15, 1940 – April 3, 2020), known as "The Unicorn Killer", was an American environmental activist and convicted murderer. His moniker, "the Unicorn", was derived from his surname; Einhorn means "unicorn" in German. As an environmental activist, Einhorn was a speaker at the first Earth Day event in Philadelphia in 1970.[1] On September 9, 1977, Einhorn's ex-girlfriend Holly Maddux disappeared following a trip to collect her belongings from the apartment she and Einhorn had shared in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Eighteen months later, police found her partially decomposed body in a trunk in Einhorn's closet.[2] After his arrest, Einhorn fled the country and spent twenty-two years in Europe before being extradited to the United States. He took the stand in his own defense, claiming his ex-girlfriend had been killed by CIA agents who had framed him for the crime because he knew too much about the agency's paranormal military research. He was convicted of murdering Holly Maddux and served a life sentence until his death in prison on April 3, 2020.[2][3] Early life and educationIra Einhorn was born in Philadelphia into a middle-class Jewish family.[2][4] As a student at the University of Pennsylvania, where he received his undergraduate degree in English in 1961 before returning to complete some graduate work in the discipline in 1963,[5][6] he became active in ecological groups and was part of the counterculture, anti-establishment, and anti-war movements of the 1960s and 1970s.[2] Career and activismEinhorn was a speaker at the first Earth Day event in Philadelphia in 1970[1] and later claimed to have been instrumental in creating and launching the event,[2] but event organizers dispute his account.[7][8] Einhorn served as an instructor of English at Temple University during the 1964–1965 academic year, although his contract was not renewed after he conceded his "contempt for the academic world" and boasted of proffering "straight answers about the delights and dangers" of cannabis and LSD to students in an interview.[9] He also was a resident fellow at the Harvard Institute of Politics during the autumn 1978 semester.[6][10][11] Murder of Holly MadduxEinhorn had a five-year relationship with Holly Maddux, a graduate of Bryn Mawr College who was from Tyler, Texas. In 1977, Maddux broke up with Einhorn and went to New York City, where she became involved with Saul Lapidus. On September 9, 1977, Maddux returned to the Powelton Village apartment[12] she had previously shared with Einhorn to collect her belongings (which Einhorn had reportedly threatened to throw out into the street as trash) and was never seen again. Several weeks later, the Philadelphia police questioned Einhorn about her disappearance. He claimed that Maddux had gone out to the neighborhood co-op to buy some tofu and sprouts, and never returned. Einhorn's initial alibi came into question when his neighbors began complaining about a foul smell coming from his apartment, which in turn aroused the suspicion of authorities. During this time, Einhorn was dating filmmaker Cecelia Condit, who could not smell the body due to medication she was on affecting her smell. Condit would later go on to make the short film Beneath the Skin about this experience.[13] Eighteen months later, on March 28, 1979, Maddux's decomposing corpse was found by police in a trunk stored in Einhorn's closet. After finding the body, a police officer reportedly said to Einhorn, "It looks like we found Holly," to which he reportedly replied, "You found what you found." Einhorn's lawyer, Arlen Specter, negotiated bail of $40,000; he was released from custody after posting a bond of $4,000, or 10% of the $40,000. This was paid by Barbara Bronfman (née Baerwald), a Montreal socialite who married into the wealthy Bronfman family and met Einhorn through a shared interest in the paranormal.[6] During Einhorn's flight he was again aided by Bronfman, who continued to support him financially until 1988, when she read Steven Levy's damning book on Einhorn, The Unicorn's Secret.[6][14] In 1981, just days before his murder trial was to begin, Einhorn skipped bail and fled to Europe. He lived there for the next seventeen years and married a Swedish woman named Annika Flodin. In Pennsylvania, as Einhorn had already been arraigned, the state convicted him in absentia of Maddux's murder in 1996. Einhorn was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. ExtraditionIn 1997, Einhorn was arrested in Champagne-Mouton, France, where he had been living under the name "Eugène Mallon" and incarcerated for about six months at the local Gradignan jail before he was placed under a loose form of house arrest. The extradition process proved more complex than initially envisioned. Under the extradition treaty between France and the United States, either country may refuse extradition under certain circumstances, and Einhorn used multiple avenues to avoid extradition. Although Einhorn was not sentenced to death, his defense attorneys argued that he would face the death penalty if he were returned to the United States. France, like many countries that have abolished the death penalty, does not extradite defendants to jurisdictions that retain the death penalty without assurance that it will be neither sought nor applied. Pennsylvania authorities pointed out that when the murder occurred, the state did not practice the death penalty and so Einhorn could not be executed because the state and federal constitutions forbid ex post facto law. Einhorn's next strategy involved French law and the European Court of Human Rights, which require a new trial when the defendant was tried in absentia and unable to present his defense. On this basis, the court of appeals of Bordeaux rejected the extradition request. Following the court's decision, thirty-five members of Congress sent a letter to French President Jacques Chirac to ask for Einhorn's extradition. However, under France's doctrine of the separation of powers, which was invoked in this case, the President cannot give orders to courts and does not intervene in extradition affairs. Therefore, in 1998, to secure Einhorn's extradition, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a bill, nicknamed the "Einhorn Law", allowing defendants convicted in absentia to request another trial. In another delay tactic, Einhorn's attorneys criticized the bill as unconstitutional and tried to get the French courts to once again deny the extradition on the grounds that the law would be inapplicable. However, the French court ruled itself unable to evaluate the constitutionality of foreign laws. Another point of friction with the United States was that the court freed Einhorn under police supervision, as French laws put restrictions on remand, the imprisonment of suspects awaiting trial. Einhorn then became the focus of intense surveillance by French police. The matter went before Prime Minister Lionel Jospin; extraditions, after having been approved by courts, must be ordered by the executive. The French Green Party stated that Einhorn should not be extradited until it was certain that the "Einhorn Law" could not be reversed.[15] Jospin rejected the claims and issued an extradition decree. Einhorn then litigated against the decree before the Conseil d'État, which ruled against him; again, the Council declined to review the constitutionality of foreign law.[16] He then attempted to slit his own throat to avoid imprisonment[17] and eventually litigated his case before the European Court of Human Rights, which also ruled against him. On July 20, 2001, Einhorn was extradited to the United States.[18] Trial and sentencingTaking the stand in his own defense, Einhorn claimed that Maddux was murdered by CIA agents, who attempted to frame him due to his investigations into the Cold War and psychotronics.[19] After two hours of deliberation, the jury convicted Einhorn on October 17, 2002, concluding the month-long trial.[5] The following day, he was sentenced to a mandatory life term without the possibility of parole.[20] Einhorn began serving his sentence at Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution (SCI) Houtzdale. In November 2006, Einhorn's sentence was unanimously affirmed by the Superior Court of Pennsylvania.[21] DeathOn April 3, 2020, Einhorn died in the Pennsylvania SCI Laurel Highlands.[22] His death was reported to be of natural causes.[23] See alsoCitations

General and cited references

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||