|

Italian battleship Giulio Cesare

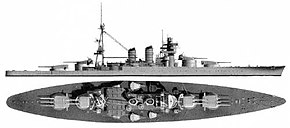

Giulio Cesare was one of three Conte di Cavour-class dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) in the 1910s. Completed in 1914, she was little used and saw no combat during the First World War. The ship supported operations during the Corfu Incident in 1923 and spent much of the rest of the decade in reserve. She was rebuilt between 1933 and 1937 with more powerful guns, additional armor and considerably more speed than before. During World War II, both Giulio Cesare and her sister ship, Conte di Cavour, participated in the Battle of Calabria in July 1940, when the former was lightly damaged. They were both present when British torpedo bombers attacked the fleet at Taranto in November 1940, but Giulio Cesare was not damaged. She escorted several convoys to North Africa and participated in the Battle of Cape Spartivento in late 1940 and the First Battle of Sirte in late 1941. She was designated as a training ship in early 1942, and escaped to Malta after the Italian armistice the following year. The ship was transferred to the Soviet Union in 1949 and renamed Novorossiysk (Новороссийск). The Soviets also used her for training until she was sunk in 1955, with the loss of 617 men, by an explosion most likely caused by an old German mine. She was salvaged the following year and later scrapped. DescriptionThe Conte di Cavour class was designed to counter the French Courbet-class dreadnoughts which caused them to be slower and more heavily armored than the first Italian dreadnought, Dante Alighieri.[1] The ships were 168.9 meters (554 ft 2 in) long at the waterline and 176 meters (577 ft 5 in) overall. They had a beam of 28 meters (91 ft 10 in), and a draft of 9.3 meters (30 ft 6 in).[2] The Conte di Cavour-class ships displaced 23,088 long tons (23,458 t) at normal load, and 25,086 long tons (25,489 t) at deep load. They had a crew of 31 officers and 969 enlisted men.[3] The ships were powered by three sets of Parsons steam turbines, two sets driving the outer propeller shafts and one set the two inner shafts. Steam for the turbines was provided by 24 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, half of which burned fuel oil and the other half burning both oil and coal. Designed to reach a maximum speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph) from 31,000 shaft horsepower (23,000 kW), Giulio Cesare failed to reach this goal on her sea trials, reaching only 21.56 knots (39.9 km/h; 24.8 mph) from 30,700 shp (22,900 kW). The ships carried enough coal and oil[4] to give them a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[2] Armament and armorThe main battery of the Conte di Cavour class consisted of thirteen 305-millimeter Model 1909 guns, in five centerline gun turrets, with a twin-gun turret superfiring over a triple-gun turret in fore and aft pairs, and a third triple turret amidships.[5] Their secondary armament consisted of eighteen 120-millimeter (4.7 in) guns mounted in casemates on the sides of the hull. For defense against torpedo boats, the ships carried fourteen 76.2-millimeter (3 in) guns; thirteen of these could be mounted on the turret tops, but they could be positioned in 30 different locations, including some on the forecastle and upper decks. They were also fitted with three submerged 450-millimeter (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and the third in the stern.[6] The Conte di Cavour-class ships had a complete waterline armor belt that had a maximum thickness of 250 millimeters (9.8 in) amidships, which reduced to 130 millimeters (5.1 in) towards the stern and 80 millimeters (3.1 in) towards the bow. They had two armored decks: the main deck was 24 mm (0.94 in) thick on the flat that increased to 40 millimeters (1.6 in) on the slopes that connected it to the main belt. The second deck was 30 millimeters (1.2 in) thick. Frontal armor of the gun turrets was 280 millimeters (11 in) in thickness and the sides were 240 millimeters (9.4 in) thick. The armor protecting their barbettes ranged in thickness from 130 to 230 millimeters (5.1 to 9.1 in). The walls of the forward conning tower were 280 millimeters thick.[7][8] Modifications and reconstruction Shortly after the end of World War I, the number of 76.2 mm guns was reduced to 13, all mounted on the turret tops, and six new 76.2-millimeter anti-aircraft (AA) guns were installed abreast the aft funnel. In addition two license-built 2-pounder (1.6 in (40 mm)) AA guns were mounted on the forecastle deck. In 1925–1926 the foremast was replaced by a four-legged (tetrapodal) mast, which was moved forward of the funnels,[9] the rangefinders were upgraded, and the ship was equipped to handle a Macchi M.18 seaplane mounted on the amidships turret. Around that same time, either one or both of the ships was equipped with a fixed aircraft catapult on the port side of the forecastle.[Note 1] Giulio Cesare began an extensive reconstruction in October 1933 at the Cantieri del Tirreno shipyard in Genoa that lasted until October 1937.[13] A new bow section was grafted over the existing bow which increased her length by 10.31 meters (33 ft 10 in) to 186.4 meters (611 ft 7 in) and her beam increased to 28.6 meters (93 ft 10 in). The ship's draft at deep load increased to 10.42 meters (34 ft 2 in).[11] All of the changes made increased her displacement to 26,140 long tons (26,560 t) at standard load and 29,100 long tons (29,600 t) at deep load. The ship's crew increased to 1,260 officers and enlisted men.[14] Two of the propeller shafts were removed and the existing turbines were replaced by two Belluzzo geared steam turbines rated at 75,000 shp (56,000 kW).[11] The boilers were replaced by eight Yarrow boilers. On her sea trials in December 1936, before her reconstruction was fully completed, Giulio Cesare reached a speed of 28.24 knots (52.30 km/h; 32.50 mph) from 93,430 shp (69,670 kW).[15] In service her maximum speed was about 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) and she had a range of 6,400 nautical miles (11,900 km; 7,400 mi) at a speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).[16] The main guns were bored out to 320 mm (12.6 in) and the center turret and the torpedo tubes were removed. All of the existing secondary armament and AA guns were replaced by a dozen 120 mm guns in six twin-gun turrets and eight 100 mm (4 in) AA guns in twin turrets. In addition the ship was fitted with a dozen Breda 37-millimeter (1.5 in) light AA guns in six twin-gun mounts and twelve 13.2-millimeter (0.52 in) Breda M31 anti-aircraft machine guns, also in twin mounts.[17] In 1940 the 13.2 mm machine guns were replaced by 20 mm (0.79 in) AA guns in twin mounts. Giulio Cesare received two more twin mounts as well as four additional 37 mm guns in twin mounts on the forecastle between the two turrets in 1941.[10] The tetrapodal mast was replaced with a new forward conning tower, protected with 260-millimeter (10.2 in) thick armor.[18] Atop the conning tower there was a fire-control director fitted with two large stereo-rangefinders, with a base length of 7.2 meters (23.6 ft).[18] The deck armor was increased during the reconstruction to a total of 135 millimeters (5.3 in) over the engine and boiler rooms and 166 millimeters (6.5 in) over the magazines, although its distribution over three decks, meant that it was considerably less effective than a single plate of the same thickness. The armor protecting the barbettes was reinforced with 50-millimeter (2 in) plates.[19] All this armor weighed a total of 3,227 long tons (3,279 t).[10] The existing underwater protection was replaced by the Pugliese torpedo defense system that consisted of a large cylinder surrounded by fuel oil or water that was intended to absorb the blast of a torpedo warhead. It lacked, however, enough depth to be fully effective against contemporary torpedoes. A major problem of the reconstruction was that the ship's increased draft meant that their waterline armor belt was almost completely submerged with any significant load.[19] Construction and service Giulio Cesare, named after Julius Caesar,[20] was laid down at the Gio. Ansaldo & C. shipyard in Genoa on 24 June 1910 and launched on 15 October 1911. She was completed on 14 May 1914 and served as a flagship in the southern Adriatic Sea during World War I.[21] She saw no action, however, and spent little time at sea.[9] Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, the Italian naval chief of staff, believed that Austro-Hungarian submarines and minelayers could operate too effectively in the narrow waters of the Adriatic.[22] The threat from these underwater weapons to his capital ships was too serious for him to use the fleet in an active way.[22] Instead, Revel decided to implement a blockade at the relatively safer southern end of the Adriatic with the battle fleet, while smaller vessels, such as the MAS torpedo boats, conducted raids on Austro-Hungarian ships and installations. Meanwhile, Revel's battleships would be preserved to confront the Austro-Hungarian battle fleet in the event that it sought a decisive engagement.[23]  Giulio Cesare made port visits in the Levant in 1919 and 1920. Both Giulio Cesare and Conte di Cavour supported Italian operations on Corfu in 1923 after an Italian general and his staff were murdered at the Greek–Albanian frontier; Benito Mussolini, who had been looking for a pretext to seize Corfu, ordered Italian troops to occupy the island. Cesare became a gunnery training ship in 1928, after having been in reserve since 1926. She was reconstructed at Cantieri del Tirreno, Genoa, between 1933 and 1937. Both ships participated in a naval review by Adolf Hitler in the Bay of Naples in May 1938 and covered the invasion of Albania in May 1939.[24] World War IIEarly in World War II, the ship took part in the Battle of Calabria (also known as the Battle of Punta Stilo), together with Conte di Cavour, on 9 July 1940, as part of the 1st Battle Squadron, commanded by Admiral Inigo Campioni, during which she engaged major elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet. The British were escorting a convoy from Malta to Alexandria, while the Italians had finished escorting another from Naples to Benghazi, Libya. Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, attempted to interpose his ships between the Italians and their base at Taranto. Crew on the fleets spotted each other in the middle of the afternoon and the battleships opened fire at 15:53 at a range of nearly 27,000 meters (29,000 yd). The two leading British battleships, HMS Warspite and Malaya, replied a minute later. Three minutes after she opened fire, shells from Giulio Cesare began to straddle Warspite which made a small turn and increased speed, to throw off the Italian ship's aim, at 16:00. Some rounds fired by Giulio Cesare overshot Warspite and near-missed the destroyers HMS Decoy and Hereward, puncturing their superstructures with splinters. At that same time, a shell from Warspite struck Giulio Cesare at a distance of about 24,000 meters (26,000 yd). The shell pierced the rear funnel and detonated inside it, blowing out a hole nearly 6.1 meters (20 ft) across. Fragments started several fires and their smoke was drawn into the boiler rooms, forcing four boilers off-line as their operators could not breathe. This reduced the ship's speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). Uncertain how severe the damage was, Campioni ordered his battleships to turn away in the face of superior British numbers and they successfully disengaged.[25] Repairs to Giulio Cesare were completed by the end of August and both ships unsuccessfully attempted to intercept British convoys to Malta in August and September.[26] On the night of 11 November 1940, Giulio Cesare and the other Italian battleships were at anchor in Taranto harbor when they were attacked by 21 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers from the British aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, along with several other warships. One torpedo sank Conte di Cavour in shallow water, but Giulio Cesare was not hit during the attack.[27] She participated in the Battle of Cape Spartivento on 27 November 1940, but never got close enough to any British ships to fire at them. The ship was damaged in January 1941 by splinters from a near miss during an air raid on Naples by Vickers Wellington bombers of the Royal Air Force; repairs at Genoa were completed in early February. On 8 February, she sailed from to the Straits of Bonifacio to intercept what the Italians thought was a Malta convoy, but was actually a raid on Genoa. She failed to make contact with any British forces. She participated in the First Battle of Sirte on 17 December 1941, providing distant cover for a convoy bound for Libya, and briefly engaging the escort force of a British convoy. She also provided distant cover for another convoy to North Africa in early January 1942.[28] Giulio Cesare was reduced to a training ship afterwards at Taranto and later Pola.[29] After the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943, she steamed to Taranto, putting down a mutiny and enduring an ineffective attack by five German aircraft en route. She then sailed for Malta where she arrived on 12 September to be interned. The ship remained there until 17 June 1944 when she returned to Taranto where she remained for the next four years.[30][31][Note 2] Soviet service After the war, Giulio Cesare was allocated to the Soviet Union as part of war reparations. She was moved to Augusta, Sicily, on 9 December 1948, where an unsuccessful attempt was made at sabotage. The ship was stricken from the naval register on 15 December and turned over to the Soviets on 6 February 1949 under the temporary name of Z11 in Vlorë, Albania.[30] She was renamed Novorossiysk, after the Soviet city of that name on the Black Sea. The Soviets used her as a training ship, and gave her eight refits. In 1953, all Italian light AA guns were replaced by eighteen 37 mm 70-K AA guns in six twin mounts and six singles. Also replaced were her fire-control systems and radars. This was intended as a temporary rearmament, as the Soviets drew up plans to replace her secondary 120mm mounts with the 130mm/58 SM-2 that was in development, and the 100mm and 37mm guns with 8 quadruple 45mm.[33] While at anchor in Sevastopol on the night of 28/29 October 1955, an explosion ripped a 4-by-14-meter (13 by 46 ft) hole in the forecastle forward of 'A' turret. The flooding could not be controlled, and she capsized with the loss of 617 men, including 61 men sent from other ships to assist.[34] The cause of the explosion is still unclear. The official cause, regarded as the most probable, was a magnetic RMH or LMB bottom mine, laid by the Germans during World War II and triggered by the dragging of the battleship's anchor chain before mooring for the last time. Subsequent searches located 32 mines of these types, some of them within 50 meters (160 ft) of the explosion. The damage was consistent with an explosion of 1,000–1,200 kilograms (2,200–2,600 lb) of TNT, and more than one mine may have detonated. Other explanations for the ship's loss have been proposed, and the most popular of these is that she was sunk by Italian frogmen of the wartime special operations unit Decima Flottiglia MAS who – more than ten years after the cessation of hostilities – were either avenging the transfer of the former Italian battleship to the USSR or sinking it on behalf of NATO.[35][36][37][38][39] Novorossiysk was stricken from the naval register on 24 February 1956, salvaged on 4 May 1957, and subsequently scrapped.[35] Notes

Footnotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Giulio Cesare (ship, 1914). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||