|

John W. Campbell

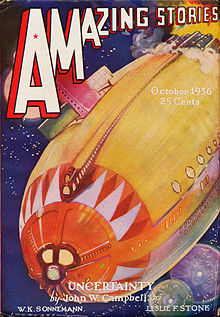

John Wood Campbell Jr. (June 8, 1910 – July 11, 1971) was an American science fiction writer and editor. He was editor of Astounding Science Fiction (later called Analog Science Fiction and Fact) from late 1937 until his death and was part of the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Campbell wrote super-science space opera under his own name and stories under his primary pseudonym, Don A. Stuart. Campbell also used the pen names Karl Van Kampen and Arthur McCann.[1] His novella Who Goes There? was adapted as the films The Thing from Another World (1951), The Thing (1982), and The Thing (2011). Campbell began writing science fiction at age 18 while attending MIT. He published six short stories, one novel, and eight letters in the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories from 1930 to 1931. This work established Campbell's reputation as a writer of space adventure. When in 1934 he began to write stories with a different tone, he wrote as Don A. Stuart. From 1930 until 1937, Campbell was prolific and successful under both names; he stopped writing fiction shortly after he became editor of Astounding in 1937. In his capacity as an editor, Campbell published some of the very earliest work, and helped shape the careers of virtually every important science-fiction author to debut between 1938 and 1946, including Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and Arthur C. Clarke. Shortly after his death in 1971, the University of Kansas science fiction program established the annual John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel and also renamed its annual Campbell Conference after him. The World Science Fiction Society established the annual John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer, since renamed the Astounding Award for Best New Writer. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted Campbell in 1996, in its inaugural class of two deceased and two living persons. BiographyJohn Campbell was born in Newark, New Jersey,[2] in 1910. His father, John Wood Campbell Sr., was an electrical engineer. His mother, Dorothy (née Strahern) had an identical twin who visited them often. John was unable to tell them apart and said he was frequently rebuffed by the person he took to be his mother.[3] Campbell attended the Blair Academy, a boarding school in rural Warren County, New Jersey, but did not graduate because of lack of credits for French and trigonometry.[4] He also attended, without graduating, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he was befriended by the mathematician Norbert Wiener (who coined the term cybernetics) – but he failed German. MIT dismissed him in his junior year in 1931. After two years at Duke University, he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in physics in 1934.[5][6][7] Campbell began writing science fiction at age 18 while attending MIT and sold his first stories quickly. From January 1930 to June 1931, Amazing Stories published six of his short stories, one novel, and six letters.[8] Campbell was editor of Astounding Science Fiction (later called Analog Science Fiction and Fact) from late 1937 until his death. He stopped writing fiction after he became the editor of Astounding. Between December 11, 1957, and June 13, 1958, he hosted a weekly science fiction radio program called Exploring Tomorrow. The scripts were written by authors such as Gordon R. Dickson and Robert Silverberg.[9] Campbell and Doña Stewart married in 1931. They divorced in 1949, and he married Margaret (Peg) Winter in 1950. He spent most of his life in New Jersey and died of heart failure at his home in Mountainside, New Jersey.[10][11] He was an atheist.[12] Writing career   Editor T. O'Conor Sloane lost Campbell's first manuscript that he accepted for Amazing Stories, entitled "Invaders of the Infinite".[6] "When the Atoms Failed" appeared in January 1930, followed by five more during 1930. Three were part of a space opera series featuring the characters Arcot, Morey, and Wade. A complete novel in the series, Islands of Space, was the cover story in the Spring 1931 Quarterly.[8] During 1934–35 a serial novel, The Mightiest Machine, ran in Astounding Stories, edited by F. Orlin Tremaine, and several stories featuring lead characters Penton and Blake appeared from late 1936 in Thrilling Wonder Stories, edited by Mort Weisinger.[8] The early work for Amazing established Campbell's reputation as a writer of space adventure. In 1934, he began to publish stories with a different tone using the pseudonym Don A. Stuart, which was derived from his wife's maiden name.[3] He published several stories under this pseudonym, including Twilight (Astounding, November 1934), Night (Astounding, October 1935), and Who Goes There? (Astounding, August 1938). Who Goes There?, about a group of Antarctic researchers who discover a crashed alien vessel, formerly inhabited by a malevolent shape-changing occupant, was published in Astounding almost a year after Campbell became its editor and it was his last significant piece of fiction, at age 28. It was filmed as The Thing from Another World (1951), The Thing (1982), and again as The Thing (2011).[13][14] Editing careerTremaine hired Campbell to succeed him[15] as the editor of Astounding from its October 1937 issue.[8][16][17] Campbell was not given full authority for Astounding until May 1938,[18] but had been responsible for buying stories earlier.[note 1][16][17][20] He began to make changes almost immediately, instigating a "mutant" label for unusual stories, and in March 1938, changing the title from Astounding Stories to Astounding Science-Fiction.[21] Lester del Rey's first story in March 1938 was an early find for Campbell. In 1939, he published a group of new writers for the in the July 1939 issue of Astounding. The July issue contained A. E. van Vogt's first story, "Black Destroyer", and Asimov's early story, "Trends"; August brought Robert A. Heinlein's first story, "Life-Line", and the next month Theodore Sturgeon's first story appeared.[22] Also in 1939, Campbell started the fantasy magazine Unknown (later Unknown Worlds).[23] Unknown was canceled after four years due to wartime paper shortages.[24] Campbell died in 1971 at the age of 61 in Mountainside, New Jersey.[25] At the time of his sudden death after 34 years at the helm of Analog, Campbell's personality and editorial demands had alienated some of his writers to the point that they no longer submitted works to him. One of his writers, Theodore Sturgeon, opted to publish most of his works after 1950 and only submitted one story with Astounding during that same timeframe.[26]  InfluenceThe Encyclopedia of Science Fiction wrote: "More than any other individual, he helped to shape modern sf",[6] and Darrell Schweitzer credits him with having "decreed that SF writers should pull themselves up out of the pulp mire and start writing intelligently, for adults".[27] After 1950, new magazines such as Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction moved in different directions and developed talented new writers who were not directly influenced by him. Campbell often suggested story ideas to writers (including "Write me a creature that thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man")[28] and sometimes asked for stories to match cover paintings he had already bought. Campbell had a strong formative influence on Asimov and eventually became a friend.[29] Asimov credited Campbell with encouraging developments within the field of science fiction field by forgoing conventional plot points and requiring its writers to "understand science and understand people."[30] He also called Campbell "the most powerful force in science fiction ever" and said the "first ten years of his editorship he dominated the field completely."[31] Campbell encouraged Cleve Cartmill to write "Deadline", a short story by that appeared during the wartime year of 1944, a year before the detonation of the first atomic bomb.[32] As Ben Bova, Campbell's successor as editor at Analog, wrote, it "described the basic facts of how to build an atomic bomb. Cartmill and Campbell worked together on the story, drawing their scientific information from papers published in the technical journals before the war. To them, the mechanics of constructing a uranium-fission bomb seemed perfectly obvious." The FBI descended on Campbell's office after the story appeared in print and demanded that the issue be removed from the newsstands. Campbell convinced them that by removing the magazine "the FBI would be advertising to everyone that such a project existed and was aimed at developing nuclear weapons" and the demand was dropped.[33] Campbell was also responsible for the grim and controversial ending of Tom Godwin's short story "The Cold Equations". Writer Joe Green recounted that Campbell had rejected Godwin's 'Cold Equations' on three different occasions due to disagreements over the fate of the female protagonist.[34] Between December 11, 1957, and June 13, 1958, Campbell hosted a weekly science fiction radio program called Exploring Tomorrow.[35] ViewsSlavery, race, and segregationGreen wrote that Campbell "enjoyed taking the 'devil's advocate' position in almost any area, willing to defend even viewpoints with which he disagreed if that led to a livelier debate". As an example, he wrote:

Finally, however, Green agreed with Campbell that "rapidly increasing mechanization after 1850 would have soon rendered slavery obsolete anyhow. It would have been better for the USA to endure it a few more years than suffer the truly horrendous costs of the Civil War."[36] In a June 1961 editorial called "Civil War Centennial", Campbell argued that slavery had been a dominant form of human relationships for most of history and that the present was unusual in that anti-slavery cultures dominated the planet. He wrote

According to Michael Moorcock, Campbell suggested that some people preferred slavery.

By the 1960s, Campbell began to publish controversial essays supporting segregation and other remarks and writings surrounding slavery and race, which distance him from many in the science fiction community.[39][38]In 1963, Campbell published an essay supporting segregated schools and arguing that "the Negro race" had failed to "produce super-high-geniuses".[40] In 1965, he continued his defense of segregation and related practices, critiquing "the arrogant defiance of law by many of the Negro 'Civil Rights' groups".[41] On February 10, 1967, Campbell rejected Samuel R. Delany's Nova a month before it was ultimately published, with a note and phone call to his agent explaining that he did not feel his readership "would be able to relate to a black main character".[42] All these views were reflected in the depiction of aliens in Astounding/Analog. Throughout his editorship, Campbell demanded that depiction of contact between aliens and humans must favor humans. For example, Campbell accepted Isaac Asimov's proposal for what would become "Homo Sol" (where humans rejected an invitation to join a galactic federation) in January 1940, which was published later that year in the September edition of Astounding Science Fiction.[43] Similarly, Arthur C. Clarke's "Rescue Party" and Fredric Brown's "Arena" (basis of the Star Trek episode of the same name) and "Letter to a Phoenix" (all first appeared in Astounding) also depict humans favorably above aliens.[44][page needed] Medicine and healthCampbell was a critic of government regulation of health and safety, excoriating numerous public health initiatives and regulations. Campbell was a heavy smoker throughout his life and was seldom seen without his customary cigarette holder. In the Analog of September 1964, nine months after the Surgeon General's first major warning about the dangers of cigarette smoking had been issued (January 11, 1964) Campbell ran an editorial, "A Counterblaste to Tobacco" that took its title from the anti-smoking book of the same name by King James I of England.[45] In it, he stated that the connection to lung cancer was "esoteric" and referred to "a barely determinable possible correlation between cigarette smoking and cancer". He said that tobacco's calming effects led to more effective thinking.[46] In a one-page piece about automobile safety in Analog dated May 1967, Campbell wrote of "people suddenly becoming conscious of the fact that cars kill more people than cigarettes do, even if the antitobacco alarmists were completely right..."[47] In 1963, Campbell published an angry editorial about Frances Oldham Kelsey who, while at the FDA, refused to permit thalidomide to be sold in the United States.[48] In other essays, Campbell supported crank medicine, arguing that government regulation was more harmful than beneficial[49] and that regulating quackery prevented the use of many possible beneficial medicines (e.g., krebiozen).[50][51] Pseudoscience, parapsychology, and politicsIn the 1930s, Campbell became interested in Joseph Rhine's theories about ESP (Rhine had already founded the Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University when Campbell was a student there),[52] and over the following years his growing interest in parapsychology would be reflected in the stories he published when he encouraged the writers to include these topics in their tales,[53] leading to the publication of numerous works about telepathy and other "psionic" abilities. This post-war "psi-boom"[54] has been dated by science fiction scholars to roughly the mid-1950s to the early 1960s, and continues to influence many popular culture tropes and motifs. Campbell rejected the Shaver Mystery in which the author claimed to have had a personal experience with a sinister ancient civilization that harbored fantastic technology in caverns under the earth. His increasing beliefs in pseudoscience would eventually start to isolate and alienate him from some of his writers, including Asimov.[55] He wrote favorably about such things as the "Dean drive", a device that supposedly produced thrust in violation of Newton's third law, and the "Hieronymus machine", which could supposedly amplify psi powers.[56][note 2][note 3] In 1949, Campbell worked closely with L. Ron Hubbard on the techniques that Hubbard later turned into Dianetics. When Hubbard's therapy failed to find support from the medical community, Campbell published the earliest forms of Dianetics in Astounding.[58] He wrote of L. Ron Hubbard's initial article in Astounding that "[i]t is, I assure you in full and absolute sincerity, one of the most important articles ever published."[56] Campbell continued to promote Hubbard's theories until 1952, when the pair split acrimoniously over the direction of the movement.[59] Asimov wrote: "A number of writers wrote pseudoscientific stuff to ensure sales to Campbell, but the best writers retreated, I among them. ..."[55] Elsewhere Asimov went on to further explain

Assessment by peersDamon Knight described Campbell as a "portly, bristled-haired blond man with a challenging stare".[60] "Six-foot-one, with hawklike features, he presented a formidable appearance," said Sam Moskowitz.[61] "He was a tall, large man with light hair, a beaky nose, a wide face with thin lips, and with a cigarette in a holder forever clamped between his teeth", wrote Asimov.[62] Algis Budrys wrote that "John W. Campbell was the greatest editor SF has seen or is likely to see, and is in fact one of the major editors in all English-language literature in the middle years of the twentieth century. All about you is the heritage of what he built".[63] Asimov said that Campbell was "talkative, opinionated, quicksilver-minded, overbearing. Talking to him meant listening to a monologue..."[62] Knight agreed: "Campbell's lecture-room manner was so unpleasant to me that I was unwilling to face it. Campbell talked a good deal more than he listened, and he liked to say outrageous things."[64] British novelist and critic Kingsley Amis dismissed Campbell brusquely: "I might just add as a sociological note that the editor of Astounding, himself a deviant figure of marked ferocity, seems to think he has invented a psi machine."[65] Several science-fiction novelists have criticized Campbell as prejudiced – Samuel R. Delany for Campbell's rejection of a novel due to the black main character,[42] and Joe Haldeman in the dedication of Forever Peace, for rejecting a novel due to a female soldier protagonist.[66] British science-fiction novelist Michael Moorcock, as part of his "Starship Stormtroopers" editorial, said Campbell's Astounding and its writers were "wild-eyed paternalists to a man, fierce anti-socialists" with "[stories] full of crew-cut wisecracking, cigar-chewing, competent guys (like Campbell's image of himself)"; they sold magazines because their "work reflected the deep-seated conservatism of the majority of their readers, who saw a Bolshevik menace in every union meeting". He viewed Campbell as turning the magazine into a vessel for right-wing politics, "by the early 1950s ... a crypto-fascist deeply philistine magazine pretending to intellectualism and offering idealistic kids an 'alternative' that was, of course, no alternative at all".[38] SF writer Alfred Bester, an editor of Holiday Magazine and a sophisticated Manhattanite, recounted at some length his "one demented meeting" with Campbell, a man he imagined from afar to be "a combination of Bertrand Russell and Ernest Rutherford". The first thing Campbell said to him was that Freud was dead, destroyed by the new discovery of Dianetics, which, he predicted, would win L. Ron Hubbard the Nobel Peace Prize. Campbell ordered the bemused Bester to "think back. Clear yourself. Remember! You can remember when your mother tried to abort you with a button hook. You've never stopped hating her for it." Bester commented: "It reinforced my private opinion that a majority of the science-fiction crowd, despite their brilliance, were missing their marbles."[67] Asimov remained grateful for Campbell's early friendship and support. He dedicated The Early Asimov (1972) to him, and concluded it by stating that "There is no way at all to express how much he meant to me and how much he did for me except, perhaps, to write this book evoking, once more, those days of a quarter century ago".[68] His final word on Campbell was that "in the last twenty years of his life, he was only a diminishing shadow of what he had once been."[55] Even Heinlein, perhaps Campbell's most important discovery and a "fast friend",[69] tired of him.[70][71] Poul Anderson wrote that Campbell "had saved and regenerated science fiction", which had become "the product of hack pulpsters" when he took over Astounding. "By his editorial policies and the help and encouragement he gave his writers (always behind the scenes), he raised both the literary and the intellectual standard anew. Whatever progress has been made stems from that renaissance".[72] Awards and honorsCampbell and Astounding shared one of the inaugural Hugo Awards with H. L. Gold and Galaxy at the 1953 World Science Fiction Convention.[73] Subsequently, Campbell and Astounding won the Hugo Award for Best Professional Editor seven additional times as well as winning the Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine four times. Campbell and Analog won the Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine yet another four times and Campbell's novella Who Goes There? also won a Hugo Award for Best Novella, bringing his total award count to seventeen.[74][75] Shortly after Campbell's death, the University of Kansas science fiction program—now the Center for the Study of Science Fiction—established the annual John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel and also renamed after him its annual Campbell Conference. The World Science Fiction Society established the annual John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. All three memorials became effective in 1973. However, following Jeannette Ng's August 2019 acceptance speech of the award for Best New Writer at Worldcon 77, in which she criticized Campbell's politics and called him a fascist, the publishers of Analog magazine announced that the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer would immediately be renamed to "The Astounding Award for Best New Writer".[76] The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted Campbell in 1996, in its inaugural class of two deceased and two living persons.[77] Campbell and Astounding shared one of the inaugural Hugo Awards with H. L. Gold and Galaxy at the 1953 World Science Fiction Convention. Subsequently, he won the Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine seven times to 1965.[78] In 2018, he won a retrospective Hugo Award for Best Editor, Short Form (1943).[74] The Martian impact crater Campbell was named after him.[79] WorksThis shortened bibliography lists each title once. Some titles that are duplicated are different versions, whereas other publications of Campbell's with different titles are simply selections from or retitlings of other works, and have hence been omitted. The main bibliographic sources are footnoted from this paragraph and provided much of the information in the following sections.[6][17][80][81][82] Novels

Short story collections and omnibus editions

Edited books

Nonfiction

Memorial worksMemorial works (Festschrift) include:

See alsoExplanatory notes

ReferencesCitations

General and cited references

Further reading

Nevala-Lee, Alec. "Astounding" 2018. Morrow/Dey Street. ISBN 9780062571946 External linksAudioWikiquote has quotations related to John W. Campbell.

Biography and criticism

Bibliography and works

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||