|

Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic)

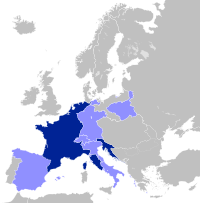

The Kingdom of Naples (Italian: Regno di Napoli; Neapolitan: Regno 'e Napule) was a French client state in southern Italy that existed from 1806 to 1815. It was founded after the Bourbon Ferdinand IV & III of Naples and Sicily sided with the Third Coalition against Napoleon, and was in return ousted from his kingdom by a French invasion. Joseph Bonaparte, elder brother of Napoleon, was installed in his stead: Joseph conferred the title "Prince of Naples" to be hereditary on his children and grandchildren. When Joseph became king of Spain in 1808, Napoleon appointed his brother-in-law Marshal Joachim Murat to take his place. Murat was later deposed by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 after striking at Austria in the Neapolitan War, in which he was decisively defeated at the Battle of Tolentino. BackgroundKing Ferdinand IV of Naples and his wife, Queen Maria Carolina of Austria, were fervent opponents of Revolutionary France and Napoleon Bonaparte, whom the queen called a "Corsican bastard, full of wickedness" in her correspondence with Marzio Mastrilli, the Neapolitan ambassador to France.[1] In the lead up to the War of the Third Coalition in 1805, Maria Carolina assured the French ambassador to Naples, Charles-Jean-Marie Alquier, that her country would remain neutral during the conflict. In Paris, a treaty providing for Neapolitan neutrality in exchange for the evacuation of ports occupied by the French Army was even signed on 21 September by Mastrilli and French Foreign Minister Talleyrand. However, the Neapolitan sovereigns were playing a double game: a secret treaty had been signed on 10 September in Naples with the Russian emissary Alexander Tatishchev. Under this treaty, King Ferdinand allowed Coalition troops to be stationed in his kingdom and placed his army under Russian command.[2] On 14 October, in accordance with the Franco-Neapolitan treaty, French troops commanded by General Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr began their withdrawal, but in the weeks that followed a Russian and British expeditionary force landed in Naples. By late November, the Russo-Neapolitan army marched on the Kingdom of Italy. While Napoleon initially had not considered invading southern Italy, Naples' betrayal changed his mind.[2] The creation of a Kingdom of Naples under French domination was therefore a result of the circumstances of the conflict, as the French emperor at first envisaged a simple alliance.[3] French conquest of NaplesOn 27 December, the day after the signing of the Treaty of Pressburg between France and Austria, Napoleon declared at the Schönbrunn Palace: "The dynasty of Naples has ceased to reign. Its existence is incompatible with the peace of Europe and the honour of my crown."[2] At the same time, General Gouvion Saint-Cyr marched on Naples at the head of an army of 40,000 men, formed on 9 December. He was first replaced by General André Masséna and then, by an imperial decree of 6 January 1806, by Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's older brother, who was promoted to general of division with the title of Lieutenant of the Emperor on this occasion. Napoleon intended to prolong the effect of the Battle of Austerlitz to drive the Austrian and Russian troops out of Italy while seizing the Kingdom of Naples, the last possession of the House of Bourbon in the peninsula. The campaign was all the more favourable to the French as the Anglo-Russian expeditionary force retreated towards Calabria, leaving the Neapolitans to their own devices.[2] Capua was taken by the French on 6 February. The next day, Queen Maria Carolina implored Napoleon's pardon, but to no avail.[4] On 15 February, Joseph Bonaparte solemnly entered Naples. Ferdinand IV and Maria Carolina fled to Sicily and made Palermo the new capital of their domain, now reduced to the Kingdom of Sicily. The invasion of Naples continued for several months. British troops defended Calabria and even scored a victory at Maida on 4 July against the troops of General Jean Reynier. The region was not pacified until the end of the summer, after the intervention of Masséna's troops, while Gaeta, defended by Prince Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal, who refused to obey orders to surrender, fell after a siege of almost five months.[2][5] Joseph Bonaparte's reign Once he had taken control of the country, Joseph Bonaparte began organizing its institutions. On 30 March 1806, Napoleon signed an act at the Tuileries in which he named his brother Joseph "King of Naples and Sicily". Joseph thus became the first of Napoleon's siblings to be made ruler of a European state.[2] He took the regnal name Joseph Napoleon (Giuseppe Napoleone).[6] Control of Naples was of key importance for the French Empire because it allowed it to complete its conquest of the Italian peninsula, except for the Papal States and the Republic of San Marino, while ensuring control of the maritime routes of the Mediterranean and the Adriatic seas. Having barely been named king, Joseph Bonaparte was thus charged with taking his place in the war against the United Kingdom. This was announced to him by a delegation from the Sénat conservateur, sent to Naples by Napoleon and composed of Pierre-Louis Roederer, Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon and Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino, who were received by Joseph on 11 May. In his correspondence with his brother, Napoleon indicated to him that his sovereignty would only assured after the arrival of the senators, a way of showing that his kingdom was directly integrated into the French system.[2] From his accession to the throne, Joseph sought to cultivate the image of a "reforming king concerned with the well-being of his subjects", compared to a "Ferdinand IV, hardly concerned with the fate of his people."[7] He became personally involved, not only to please his brother, but because he thought it necessary.[5] He therefore presided over the councils, summoned or wrote to his generals and administrators in a manner similar to that of the emperor, and annotated dossiers and reports. But he had to maintain a repressive apparatus in the face of plots and revolts, and act in a context constrained by the international situation. ReformsIn the modernising spirit of the French Revolution, King Joseph Napoleon implemented a programme of sweeping reforms to the organisation and structure of the ancient feudal kingdom. The Neapolitan nobility in its majority welcomed the change of regime with benevolence, while expecting guarantees and the consolidation of the new authority, as the local elites were tired of the authoritarianism of former queen Marie Caroline of Austria. Under Joseph, the monarchical and authoritarian framework was preserved, but in the context of an active policy of administrative, judicial, military, financial, social, educational and cultural reforms. The new sovereign appointed Pierre-Louis Roederer as Minister of Finance, Antoine Christophe Saliceti as Minister of Police and General Mathieu Dumas as Minister of War. AdministrationUpon becoming King of Naples, Joseph Bonaparte launched a series of reforms designed to ensure the shift of state structures towards rationality, order and efficiency, notably with the creation of:[5]

The territorial organization was similar to that of France: it saw the creation of thirteen provinces, headed by an intendant, and forty-two districts, headed by a sub-intendant. King Joseph, however, went further by promulgating the Law of 8 December 1806, determining that the 2,520 communes of the kingdom would be grouped into 495 "governments", even more structuring than the French cantons. Finances In 1806, the financial situation of Naples was catastrophic. The coffers were empty, the royal palaces emptied of their furniture, and the banks' cash reserves had been taken to Sicily by the fleeing Bourbons. Minister of Finance Roederer was responsible for the debt and tax collection projects and focused his efforts on reforming property taxes.[8] The King of Naples and his officials sought to implement austerity where clientelism had previously prevailed. He turned to Roman bankers, but despite all efforts the income was insufficient and the financial situation remained precarious. To carry out his policy, part of the royal domain of the properties belonging to the State, émigrés and the Catholic Church was sold. Joseph finally decreed an exceptional tax of 22 million francs, and negotiated a loan of around 5 million francs, with an annual interest rate of six percent.[9] For daily transactions and investments, in addition to structural savings and a reduction in the number of agents, the modernization of taxation and administration was undertaken from 1806, with the establishment of new contributions, the grouping of taxes, an increase in customs tariffs, the operation of the lottery and stamp duty, the improvement of the land registry, the abolition of leases granted to barons, and the creation of the Public Debt Ledger.[5] The collection of all taxes was slowly brought under a central revenue service as the government brought out the contractors and compensated those who had lost their feudal tax-collecting privileges with bonds.[10] Joseph, who personally chaired the Council of Finances, encouraged the merger of the establishments, leaving it to Joachim Murat to create in 1809 the Bank of the Two Sicilies, designed according to the model of the Bank of France.[5] Military From July 1806, the French model was adopted for the profound reorganization of the Neapolitan Army, whose "dissolution was complete" according to Minister of War Dumas: military schools, barracks, and military hospitals were established. Based on the French National Guard, a Provincial Guard was created for the maintenance of order and the surveillance of public buildings, while Naples received a Civic Guard.[5] Legions of gendarmerie and police commissioners were instituted.[5] Although an opponent of the repressive policies often employed by Napoleon, Joseph nevertheless implemented them in Naples against his opponents, and the execution of Marquess Giambattista Rodio, who was arrested and shot without solid evidence, was reminiscent of the Duke of Enghien affair of 1804.[8] On 26 August 1806, Joseph created a Royal Guard composed of two infantry regiments, one cavalry regiment, two artillery companies and a company of elite gendarmes. The regular army was supplied by conscription, which provided under Joseph's reign a little over 60,000 men. Joseph effectively commanded the Neapolitan Army as well as the French, Italian, and Polish contingents stationed in his kingdom.[5] Social issuesOne of Joseph's first objectives as king was the abolition of feudalism. Although the political dominance of lords and the clergy had disappeared decades earlier, their economic power and influence over people's minds remained strong. In most communes, peasants continued to pay fees in kind or in cash for various aspects of rural life: land sales, seeds, water, manure, amounting to nearly 180 different levies.[7] They were also subject to the decisions of landowners regarding farming techniques and the organization of trade and markets. The system was described as a "monstrous assembly of privileges, monopolies, abuses, and usurpation."[3] By a decree of 2 August 1806, feudalism was abolished, and all the rights and privileges of the nobility suppressed.[11] The practice of tax farming was also ended.[12] Additional legislation gradually completed the decree with the liberation of the use of waterways, the abolition of several taxes, the possibility of buying back lands and the rights to exploit them, the division of collective domains, the abolition of fideicommissa which had kept certain properties and rights out of commerce and inheritance.[5] Resistance to these measures was strong, but Joseph's initiatives were continued under the reign of Joachim Murat and upheld by the restored Bourbons, who made few changes to the decisions taken during the Napoleonic decade.[13] Joseph also founded charitable organizations and hospitals to further support his reforms.[5][14] EducationUnder Joseph's reign, public istruction and intellectual life were advanced. Public education was rethought: to give provincial public colleges time to set up, he tolerated the maintenance of religious schools. He ordered the establishment of educational institutions for girls—eleven of which were set up in the capital alone—and instructed professional groups to establish conservatories for apprenticeships. Joseph directed the communes to develop primary education, and opened institutions to care for the kingdom's 5,600 foundlings.[14] ReligionContinuing the anti-clerical sentiment of the French Revolution, church property was confiscated en masse and auctioned off as biens nationaux (in compensation for the loss of feudal privileges, the nobles received a certificate which could be exchanged for such properties). However, not all church land was sold immediately, with some retained to support charitable and educational foundations.[15] Most monastic orders were also suppressed and their funds transferred to the royal treasury; the Benedictines and Jesuits were dissolved, but Joseph preserved the Franciscans.[16] Collaboration with local elitesJoseph called upon the local elites to consolidate his power and drafted acts to bring the French members of his entourage and the administration closer to the Neapolitan elites. Numerous French citizens had settled in the kingdom and acquired biens nationaux. Joseph did not take into account the negative image that the French had of the local nobility, despised due its plethora of 163 princes and 279 dukes, who often had no means to maintain their rank.[a][5] Joseph set about bringing them closer to the French, notably through marriages:[5] one of Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's daughters contracted a marriage with Prince Luperano, an important name of the kingdom, while the daughter of Minister of the Interior Saliceti was married to Prince Torella. Joseph granted Neapolitan titles to his closest allies: Charles Saligny was created Duke of San-Germano, André François Miot Count of Melito, Paul Félix Ferri-Pisani Count of Sant'Anastasio.[5] Napoleon authorized Joseph to create the Royal Order of the Two-Sicilies in 1808.[5] Under Joseph, the Royal Palace of Naples and the Palace of Capodimonte were opened to the bourgeoisie for the first time. OppositionMilitary resistanceThe first months of Joseph's reign were difficult. British troops occupied Calabria, while the city of Gaeta resisted French troops and allowed the British to have a harbor to shelter their ships. Only after an arduous siege could Joseph announce to Napoleon the capture of Gaeta. In Calabria, Masséna restored order but at the cost of many exactions. The army lacked money, equipment and reinforcements. Joseph set himself a target of 50,000 soldiers that he intended to achieve in the coming months. In the meantime, he had to ask Napoleon for support to cover the army's expenses, which was not without remarks from the Emperor: "Do not expect money from me. The 50,000 francs in gold that I sent you is the last sum that I am sending to Naples."[17] ConspiraciesNumerous plots and attacks, directly threatening the life of the king and his ministers, were foiled between 1806 and 1808. Many were fomented by the supporters of Maria Carolina of Austria and Fra Diavolo. This situation worried Napoleon, who advised his brother, in a letter dated 31 May 1806, to create a Royal Guard: "Compose your guard with 4 regiments of chasseurs and hussars. Form as well 2 battalions of grenadiers."[17] He also recommended the greatest caution: "Appoint a single commander of the guard and regard with suspicion all Neapolitans. The valets, cooks, guards must be French."[17] ConstitutionThe constitution of the Kingdom of Naples, officially the Constitutional Statute of the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Statuto costituzionale del Regno di Napoli e di Sicilia), was signed by King Joseph Napoleon on 20 June 1808, shortly before he was succeeded by Marshal Joachim Murat.[6] Joachim Murat's reign Joseph Bonaparte reigned as King of Naples for two years. On 21 May 1808, he received an order from Napoleon to go to Bayonne: "the nation, through the Council of Castile, asks me for a King. It is to you that I destine this crown."[8] Joseph became King of Spain, and the crown of Naples was offered to Marshal Joachim Murat, husband of Napoleon's sister Caroline Bonaparte. On 15 July 1808, by the Treaty of Bayonne, Murat and his wife received the crown of Naples from Napoleon. In return, the Murat couple had to give up the Grand Duchy of Berg, all their personal property and real estate in France, and Murat's salary as a Marshal of the Empire while keeping the title. In return for these abdications, Murat was named King of Naples under the regnal name Joachim Napoleon (Giacchino Napoleone).[18] He made his solemn entry into Naples on 6 September 1808. After passing under triumphal arches, he received the homage of the city's notables and had a Te Deum sung to him at Naples Cathedral.[19] As Joseph had taken the Royal Guard and the kingdom's best regiments to Spain, Murat had to reconstitute the Neapolitan Army. His experience allowed him to accomplish this task; to do so, Murat abolished the military commissions, granted amnesty to deserters, pardoned dozens of convicts sentenced to death and recalled the émigrés. Murat sought to show to Neapolitans that he was their sole sovereign and that he was fully invested in his role as king. Despite everything, this did not earn him Napoleon's praise: "I have seen decrees from you that make no sense. Why recall exiles and give property to men who conspire against me?".[20] In October 1808, General Jean Maximilien Lamarque captured the island of Capri from the British. Naples successfully defended itself against a Royal Navy squadron during the War of the Fifth Coalition in 1809. However, Murat's attempt to annex Sicily, the place of exile of the former sovereign of Naples Ferdinand I, ended in failure and once again gave Napoleon the opportunity to mark his hold on the kingdom and to show Murat that he should consider himself a subject. The Emperor demanded money, troops, and imposed on Naples the opening of its borders to French products and a strict enforcement of the Continental Blockade. Naples' financial situation remained difficult at the time of Murat's accession. Roederer, the former Minister of Finance, had left with Joseph, civil servants and soldiers had not been paid in months and the country was plagued by brigandage. With the support and advice of his Minister of Finance, Jean-Michel Agar, Murat restored part of the country's finances without raising taxes, introduced the Napoleonic Code, completed the abolition of feudalism and partially suppressed brigandage in Abruzzo and Calabria. At the same time, Caroline seconded her husband, establishing a boarding school to educate young women from Neapolitan high society. She supported the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii and promoted French art, notably painting with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Paintings produced by Ingres under Caroline's patronage include La Dormeuse de Naples (1809) and Grande Odalisque (1814).[20] Conflict with NapoleonMurat's successes as king led him to seek increasing autonomy from Napoleon, in order to reign in complete independence from the French Empire. The King of Naples thus took increasingly personal initiatives. He dismissed fellow marshal Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon as governor of Naples and replaced him with a Neapolitan lieutenant-colonel. By a decree of 17 July 1812, he determined that all French civilians and soldiers residing in Naples should be naturalized. In addition, the French flag was replaced on ships and fortresses by a new Neapolitan flag: a blue background with border forming a checkerboard with alternating white and crimson squares.[20] Faced with these initiatives, Napoleon's response was immediate: "given our decree of 30 March 1806, by virtue of which the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies is part of our Empire, considering that the prince who governs this State is French and that he was not placed on the throne but through the efforts of our people: we decree: All French citizens are citizens of the Two Sicilies. Your decree is not applicable to them."[20] Switching sides in 1814 and 1815In 1812, Murat left Caroline as regent of Naples and joined Napoleon in the disastrous Russian campaign. From his return, as Napoleon's downfall unfolded, he increasingly sought to save his kingdom. Opening communications with Austria and Britain, Murat signed a treaty with the Austrians on 11 January 1814 in which, in return for renouncing his claims to Sicily and providing military support to the Allies in the war against his former Emperor, Austria would guarantee his continued possession of Naples.[21] On 17 January, Murat issued a proclamation to the people of Italy in which he announced the side he had just taken and the goal he was pursuing: "just reasons have led us to seek an alliance with the Coalition against the Emperor of the French and we have had the good fortune of being welcomed".[19] Marching his troops north, Murat's Neapolitans joined the Austrians against Napoleon's stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of the Kingdom of Italy. After initially opening secret communications with Eugène to explore his options of switching sides again, Murat finally committed to the allied side and attacked Piacenza.[22] Upon Napoleon's abdication on 11 April 1814 and Eugène's armistice, Murat returned to Naples. However, his new allies did not trust him, and he became convinced they were about to depose him. Upon Napoleon's return from Elba in 1815, Murat struck out from Rimini at the Austrian forces in northern Italy in what he considered a pre-emptive attack. The powers at the Congress of Vienna assumed he was in concert with Napoleon, but this was, in fact, the opposite of the truth, as Napoleon was then seeking to secure recognition of his return to France through promises of peace, not war. On 2 April, Murat entered Bologna without a fight. Still, soon he was in headlong retreat as the Austrians crossed the Po at Occhiobello, and his Neapolitan forces disintegrated at the first sign of a skirmish. Murat withdrew to Cesena, then Ancona, then Tolentino.[23] At the Battle of Tolentino on 3 May 1815, the Neapolitan Army was swept aside. Though Murat escaped to Naples, his position was irrecoverable, and he soon continued his flight, leaving Naples for France. Ferdinand IV & III was soon restored, and the Napoleonic kingdom came to an end. The Congress of Vienna confirmed Ferdinand in possession of both his ancient kingdoms, Naples and Sicily, which were united in 1816 as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which would survive until 1861. State symbols

Notes

References

Sources

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||