|

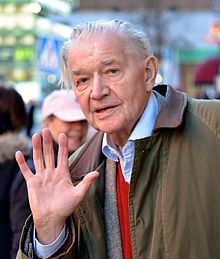

Lennart Nilsson

Lennart Nilsson (24 August 1922 – 28 January 2017)[1] was a Swedish photographer noted for his photographs of human embryos and other medical subjects once considered unphotographable, and more generally for his extreme macro photography. He was also considered to be among Sweden’s first modern photojournalists. BiographyLennart Nilsson was born in Strängnäs, Sweden. His father worked at the railway as a repairman[2] and gave Lennart Nilsson a camera when Lennart Nilsson was twelve years old. When he was around fifteen, he saw a documentary about Louis Pasteur that made him interested in microscopy. Within a few years, Nilsson had acquired a microscope and was making microphotographs of insects. In his late teens and twenties, he began taking a series of environmental portraits with an Icoflex Zeiss camera, and had the opportunity to photograph many famous Swedes. He began his professional career in the mid-1940s as a freelance photographer, working frequently for the publisher Åhlen & Åkerlund of Stockholm. One of his earliest assignments was covering the liberation of Norway in 1945 during World War II. Some of his early photo essays, notably A Midwife in Lapland (1945), Polar Bear Hunting in Spitzbergen (1947), and Fishermen at the Congo River (1948), brought him international attention after publication in Life, Illustrated, Picture Post, and elsewhere. In 1954, eighty-seven of his portraits of famous Swedes were published in the book Sweden in Profile. His 1955 book, Reportage, featured a selection of his early work. In 1963 his photoessay about the Swedish Salvation Army appeared in several magazines and in his book Hallelujah. In the mid-1950s he began experimenting with new photographic techniques to make extreme close-up photographs. These advances, combined with very thin endoscopes that became available in the mid-1960s, enabled him to make groundbreaking photographs of living human blood vessels and body cavities. He achieved international fame in 1965, when his photographs of the beginning of human life appeared on the cover and on sixteen pages of Life magazine, in an article titled “Drama of Life Before Birth”.[3][4][5] They were also published in Stern, Paris Match, The Sunday Times, and elsewhere. The photographs made up a part of the book A Child is Born (1965); images from the book were reproduced in the April 30, 1965 edition of Life, which sold eight million copies in the first four days after publication.[6] Some of the photographs from it were later included on both Voyager spacecraft. In an interview published by PBS, Nilsson explained how he obtained photographs of living fetuses during medical procedures including laparoscopy and amniocentesis and discussed how he was able to light the inside of the mother's womb. Describing a shoot that took place during a surgical procedure in Göteborg, he stated, "The fetus was moving, not really sucking its thumb, but it was moving and you could see everything—heartbeats and umbilical cord and so on. It was extremely beautiful, really beautiful!" Nilsson also acknowledged obtaining human embryos from women's clinics in Sweden.[7] The University of Cambridge claims that "Nilsson actually photographed abortus material... working with dead embryos allowed Nilsson to experiment with lighting, background and positions, such as placing the thumb into the fetus' mouth. But the origin of the pictures was rarely mentioned, even by anti-abortion activists, who in the 1970s appropriated these icons."[8] However, Nilsson himself has offered additional explanations for the sources of his photographs in other interviews, stating that he at times used embryos that had been miscarried due to extra-uterine or ectopic pregnancies. In 1969 he began using a scanning electron microscope on a Life assignment to depict the body's functions. He is generally credited with taking the first images of the human immunodeficiency virus, and in 2003, he took the first image of the SARS virus. Around 1970 he joined the staff of the Karolinska Institutet. Nilsson was also involved in the creation of documentaries, including: The Saga of Life (1982); The Miracle of Life (1982); Odyssey of Life (1996) and Life's Greatest Miracle (2001). Nilsson died on 28 January 2017.[9] Awards and honorsNilsson became a member of the Swedish Society of Medicine in 1969, received an honorary doctorate in medicine from Karolinska Institute in 1976,[10] an Honorary Doctor of Philosophy from the Technische Universität Braunschweig in Germany in 2002,[11] and an Honorary Doctor of Philosophy from Linköping University in Sweden in 2003.[12] He won the Swedish Academy Nordic Authors' Prize,[citation needed] the first Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography (in 1980),[13] the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences' Big Gold Medal in 1989,[14] and in 2002 received the 12th presentation of the Swedish government's Illis quorum.[15] His documentaries won Emmy awards in 1983 and 1996.[16] He was awarded the Royal Photographic Society's Progress medal in 1993 'in recognition of any invention, research, publication or other contribution which has resulted in an important advance in the scientific or technological development of photography.'[17] Nilsson's work is on exhibit in many locations, including the British Museum in London, the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, and the Modern Museum in Stockholm.[18] Since 1998, the Lennart Nilsson Award has been presented annually during the Karolinska Institute's installation ceremony. It is given in recognition of extraordinary photography of science and is sponsored by the Lennart Nilsson Foundation. WorksBooks

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Lennart Nilsson. |

||||||||||||||||||