|

Libellus responsionum

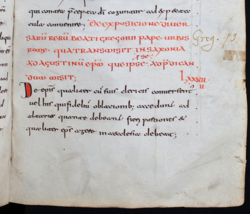

The Libellus responsionum (Latin for "little book of answers") is a papal letter (also known as a papal rescript or decretal) written in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Augustine of Canterbury in response to several of Augustine's questions regarding the nascent church in Anglo-Saxon England.[1] The Libellus was reproduced in its entirety by Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, whence it was transmitted widely in the Middle Ages, and where it is still most often encountered by students and historians today.[2] Before it was ever transmitted in Bede's Historia, however, the Libellus circulated as part of several different early medieval canon law collections, often in the company of texts of a penitential nature. The authenticity of the Libellus (notwithstanding Boniface's suspicions, on which see below) was not called into serious question until the mid-twentieth century, when several historians forwarded the hypothesis that the document had been concocted in England in the early eighth century.[3] It has since been shown, however, that this hypothesis was based on incomplete evidence and historical misapprehensions. In particular, twentieth-century scholarship focused on the presence in the Libellus of what appeared to be an impossibly lax rule regarding consanguinity and marriage, a rule that (it was thought) Gregory could not possibly have endorsed. It is now known that this rule is not in fact as lax as historians had thought, and moreover that the rule is fully consistent with Gregory's style and mode of thought.[4] Today, Gregory I's authorship of the Libellus is generally accepted.[5] The question of authenticity aside, manuscript and textual evidence indicates that the document was being transmitted in Italy by perhaps as early as the beginning of the seventh century (i.e. shortly after Gregory I's death in 604), and in England by the end of the same century. CreationThe Libellus is a reply by Pope Gregory I to questions posed by Augustine of Canterbury about certain disciplinary, administrative, and sacral problems he was facing as he tried to establish a bishopric amongst the Kentish people following the initial success of the Gregorian mission in 596.[6] Modern historians, including Ian Wood and Rob Meens, have seen the Libellus as indicating that Augustine had more contact with native British Christians than is indicated by Bede's narrative in the Historia Ecclesiastica.[7] Augustine's original questions (no longer extant) would have been sent to Rome around 598, but Gregory's reply (i.e. the Libellus) was delayed some years due to illness, and was not composed until perhaps the summer of 601.[8] The Libellus may have been brought back to Augustine by Laurence and Peter, along with letters to the king of Kent and his wife and other items for the mission.[9] However, some scholars have suggested that the Libellus may in fact never have reached its intended recipient (Augustine) in Canterbury.[10] Paul Meyvaert, for example, has noted that no early Anglo-Saxon copy of the Libellus survives that is earlier than Bede's Historia ecclesiastica (c. 731), and Bede's copy appears to derive not from a Canterbury file copy but rather from a Continental canon law collection.[11] This would be strange had the letter arrived in Canterbury in the first place. A document as important to the fledgling mission and to the history of the Canterbury church as the Libellus is likely to have been protected and preserved quite carefully by Canterbury scribes; yet this seems not to have been the case. Meyvaert therefore suggested that the Libellus may have been waylaid on its journey north from Rome in 601, and only later arrived in England, long after Augustine's death.[12] This hypothesis is supported by the surviving manuscript and textual evidence, which strongly suggests that the Libellus circulated widely on the Continent for perhaps nearly a century before finally arriving in England (see below). Still, the exact time, place, and vector by which the Libellus arrived in England and fell into the hands of Bede (and thence his Historia Ecclesiastica) is still far from certain, and scholars continue to explore these questions.[13] TitleGregory does not appear to have provided the Libellus with a title. This is not unusual since the work is a letter and Gregory was not in the habit of titling his many letters. "Libellus responsionum" is the name given the letter by Bede in his Historia Ecclesiastica,[14] and most modern commentators translate Bede's nomenclature as "Little book of answers" or "Little book of responses". "Libellus" can also be translated as "letter";[15] thus "Letter of answers" is another possible translation. ContentsThe Libellus consists of a series of responses (responsiones) by Gregory to "certain jurisprudential, administrative, jurisdictional, liturgical and ritual questions Augustine was confronted with as leader of the fledgling English church".[16] The numbering and order of these responses differ across the various versions of the Libellus (see below). But in the most widely known version (that reproduced in Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica) there are nine responses, each of which begins by re-stating or paraphrasing Augustine's original questions.[17] Gregory's first response addresses questions about the relationship of a bishop to his clergy and vice versa, how gifts from the laity to the church should be divided amongst the clergy, and what the tasks of a bishop were.[18] The second response addresses why the various northern European churches of which Augustine was aware had differing customs and liturgies, and what Augustine should do when he encounters such differences. The third response was in answer to questions about the proper punishment of church robbers.[19] The fourth and fifth responses deal with who might marry whom, including whether it was allowed for two brothers to marry two sisters, or for a man to marry his step-sister or step-mother.[20] The sixth response addresses whether or not it was acceptable for a bishop to be consecrated without other bishops present, if the distances involved prevented other bishops from attending the ceremony.[21] The seventh response deals with relations between the church in England and the church in Gaul.[22] The eighth response concerns what a pregnant, newly delivered, or menstruating woman might do or not do, including whether or not she is allowed to enjoy sex with her husband and for how long after child-birth she has to wait to re-enter a church.[23] The last response answers questions about whether or not men might have communion after experiencing a sexual dream, and whether or not priests might celebrate mass after experiencing such dreams.[24] An additional chapter, not included by Bede in his Historia is known as the "Obsecratio": it contains a response by Gregory to Augustine's request for relics of the local British martyr Sixtus. Gregory responds that he is sending relics of Pope Sixtus II to replace the local saint's remains, as Gregory has doubts about the actual saintly status of the British martyr. Although the authenticity of the "Obsecratio" has occasionally been questioned, most modern historians accept that it is genuine.[25] Later useIn the early seventh century an augmented version of the Dionysian conciliar and decretal collections was assembled in Bobbio, in northern Italy.[26] To this canon law collection — known today as the Collectio canonum Dionysiana Bobiensis[27] —there was appended at some time a long series of additional papal documents and letters, including the Libellus responsionum and Libellus synodicus. Some scholars date the addition of this series of documents to as early as the seventh century.[28] Klaus Zechiel-Eckes has even suggested the first half of the seventh century as the date for when the addition was made, that is only shortly after the Bobiensis’s initial compilation and at most only fifty years after Gregory's death.[29] If Zechiel-Eckes's dating is correct, it would make the Collectio Bobiensis the earliest surviving witness by far to the Libellus.[26] How and when the Libellus eventually reached England is not clear. It is not known if the original letter ever reached Augustine, its intended recipient. Bede assumed that it had, though he is rather vague on specifics at this point.[30] On the strength of Bede's word alone many later historians have claimed that the Libellus reached Augustine in a timely fashion;[31] however, as mentioned above, recent scholarship has brought this assumption into serious question. In any event, some version of the letter seems to have been available in England by the late seventh century, for it was then that it was quoted by Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury, in a series of judgments known today as the Paenitentiale Theodori.[32] It is possible that Theodore found a copy of the Libellus already at Canterbury; however, given that no one in England previous to Theodore's archiepiscopacy seems to have known of the Libellus, it is equally plausible that the Libellus was one of the texts that Theodore brought with him from Italy when he arrived in Canterbury in 669. It is known that Theodore brought numerous books with him from Italy, and that at least one of these books was a canon law collection very much like the one prepared at Bobbio some decades earlier (i.e. the Bobiensis).[33] Elliot has speculated that Theodore introduced a Bobiensis-type collection to Canterbury in the second half of the seventh century, and thereby finally delivered the Libellus (as part of the Bobbiensis) to its originally intended destination.[34] This hypothesis is supported by the fact that it was only shortly after Theodore's tenure at Canterbury that Anglo-Saxons begin to demonstrate knowledge of the Libellus.[35] Bede inserted the entire text of the Libellus into book I of his Historia Ecclesiastica (completed ca. 731), where it makes up the bulk of chapter 27.[36] Bede also appears to have relied upon the Libellus while writing his prose Vita Sancti Cuthberti in about the year 720.[37] Where Bede acquired his copy of the Libellus is not known, but it seems that by the early eighth century it was beginning to be read widely throughout northern England.[38] In the later Middle Ages, the text of the Libellus was used to support the claims of the monks of the Canterbury Cathedral chapter that the chapter had always included monks, back to the founding of the cathedral by Augustine. But the Libellus does not explicitly say that the cathedral chapter should be composed of monks, only that the monks that were members of the chapter should live in common and have some other aspects of monastic life.[39] Controversy over authenticityTwentieth-century scholarship's focus on the doubt expressed by Boniface regarding the authenticity of the Libellus has led to the widely held belief that a general atmosphere of suspicion surrounded the Libellus in the Middle Ages. In fact, Boniface appears to have been the only medieval personality to have ever expressed doubt about the authorship of this letter.[40] As missionary to the Germanic peoples of Europe and legate of the papal see, Boniface spent much of his later life in Continental Europe, where he encountered many canonical traditions that were unfamiliar to the Anglo-Saxons and that appeared to Boniface out of step with his knowledge of church tradition. The Libellus represented one such tradition. Boniface in fact had very practical reasons for questioning the Libellus. He had witnessed its recommendations being exploited by certain members of the Frankish nobility who claimed that the Libellus permitted them to enter into unions with their aunts, unions Boniface considered to be incestuous.[41] Eager to get to the bottom of this controversy, in 735 Boniface wrote to Nothhelm, the Archbishop of Canterbury, requesting Nothhelm send him Canterbury's own copy of the Libellus; presumably Boniface hoped that Canterbury (being the one-time residence of Augustine) possessed an authentic copy of the Libellus, one that perhaps preserved more ancient readings than the copies then circulating in France and Bavaria, and would therefore serve as a corrective to the Continental copies and the incestuous nobles who relied upon them. Boniface also requested Nothhelm's opinion on the document's authenticity, for his own inquiries at the papal archives had failed to turn up an official "registered" copy of the letter there. His failed attempt to locate a "registered" papal copy of the Libellus presumably suggested to Boniface the possibility that the document was spurious and had in fact not been authored by Pope Gregory I.[42] Boniface had specific concerns about the wording of the Libellus. At least three versions of the Libellus were circulating on the Continent during Boniface's lifetime, all of these within collections of canonical and penitential documents. Boniface is known to have encountered (perhaps even helped produce) at least one canon law collection — the Collectio canonum vetus Gallica — that included the "Q/A" version of the Libellus, and it is also possible that he knew of the Collectio Bobiensis, with its appended "Capitula" version of the Libellus.[43] A third version of the Libellus known as the "Letter" version may also have been known to Boniface.[44] There are slight differences in wording and chapter order between the three versions, but for the most part they are the same, with one important exception: the "Q/A" and "Capitula" versions contain a passage that discusses how closely a man and a woman can be related before they are prohibited from being married; the "Letter" version omits this passage. According to Karl Ubl and Michael D. Elliot, the passage in the "Q/A" and "Capitula" versions is authentic, and its absence from the "Letter" version represents a later modification of the text probably made in the mid-seventh century.[45] The passage in the "Q/A" and "Capitula" versions has Gregory saying that those related within the second degree of kinship (including siblings, parents and their children, first cousins, and nephews/nieces and their aunts/uncles) are prohibited from marrying each other, but that church tradition sets no prohibition against marrying a more distant relation. However, Gregory used a method of reckoning degrees of kinship (or consanguinity) that was unfamiliar to many living in the mid-eighth century. Ubl has shown that Gregory's method of reckoning degrees of kinship was one that would come to be known as the "scriptural" or "canonical" method.[46] Boniface, the papacy, and apparently most of Western Europe ca. 750 followed a different method of reckoning, known as the "Roman" method, whereby a restriction within the second degree merely precluded siblings from marrying each other and parents from marrying their children, and implicitly allowed all unions beyond these.[47] Thus, Boniface (misinterpreting Gregory's "canonical" method of measuring kinship for a "Roman" one) took this passage in the Libellus to mean that Gregory permitted first cousins to marry each other and nephews/nieces to marry their aunts/uncles — an opinion that Boniface (rightly) believed Gregory would not have held.[48] Boniface seems to have been unable to correct his misunderstanding of the meaning of the Libellus on this point. But this was perhaps due as much to the fact that seventh- and eighth-century canonical authorities (especially popes) so frequently conflicted on this subject, as to Boniface's own interpretative error. In a long series of letters written to subsequent bishops of Rome — Pope Gregory II, Pope Gregory III, Pope Zachary — Boniface periodically brought up the issue of consanguinity and marriage, and each time he received a slightly different answer as to what was permitted and what was prohibited.[49] Suspicion about the authenticity of the Libellus seems to have ended with Boniface's death in 754, though misinterpretation of its chapter on consanguinity continued for long after that. Nevertheless, no medieval authority except Boniface is on record as ever having questioned the authenticity of the Libellus and its marriage chapter. In fact, there arose a vigorous tradition of forged documents that defended the authenticity of the Libellus and attempted to explain why it permitted, or (to those who followed the "Roman" system) seemed to permit, nieces to marry their uncles, or even first cousins to marry.[50] Boniface's doubts about the Libellus were revived in the twentieth century by several modern historians. In 1941 Suso Brechter made a study of the historical sources for Gregory the Great's Anglo-Saxon mission. In this study Brechter attempted to prove that the Libellus was an eighth-century forgery by Nothhelm. He believed that the Libellus contained too much that pertained specifically to eighth-century (rather than late sixth-century) theological concerns, i.e. the concerns of Nothhelm rather than Augustine. He argued that the forgery was completed in 731 and was foisted on Bede by Nothhelm in that year, making it a late insertion into Bede's Historia.[51] Brechter's work did not attract much scholarly interest until 1959, when Margaret Deanesly and Paul Grosjean wrote a joint journal article refuting or modifying most of Brechter's arguments about the Libellus. Deanesly and Grosjean thought that Nothhelm had collected genuine Gregorian letters, added to them material relating to theological questions current at Canterbury, and presented the finished product (or dossier) to Bede as a "Gregorian" work: what we now know as the Libellus responsionum. They further argued that Nothhelm did this in two stages: a first stage that they named the Capitula version,[52] which they considered was best exemplified by a manuscript now in Copenhagen; and a second version, which was rearranged in the form of questions paired with answers.[53] In their view, this second version was the work sent to Bede by Nothhelm.[54] The upshot of Deanesly and Grosjean's research was that the Libellus was quasi-authentic: while not a genuine work of Gregory I, it was nevertheless based extensively on authentic Gregorian writings.[55] Deanesly and Grosjean's thesis was addressed and refuted by the textual research of Paul Meyvaert,[56] following whose work most scholars have come to accept the Libellus as a genuine letter of Gregory.[57][58][59][60] The only portion of the Libellus that Meyvaert could not accept as genuine was the chapter on marriage, which Meyvaert (like Boniface before him) believed could not have been written by Gregory. Meyvaert therefore pronounced this chapter to be the single interpolation in an otherwise genuine document.[61] All subsequent scholarship up until the year 2008 has followed him on this point.[62] In 2008 Ubl not only showed that the marriage chapter was in fact authored by Gregory, but he also explained exactly how it was the Boniface and later historians came to misunderstand its meaning. Citations

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||