|

Maputo Protocol

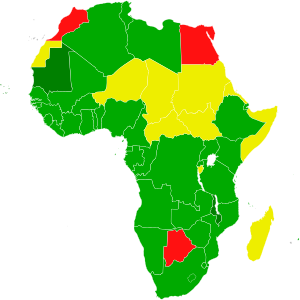

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, better known as the Maputo Protocol, is an international human rights instrument established by the African Union that went into effect in 2005. It guarantees comprehensive rights to women including the right to take part in the political process, to social and political equality with men, improved autonomy in their reproductive health decisions, and an end to female genital mutilation.[3] It was adopted by the African Union in Maputo, Mozambique, in 2003 in the form of a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (adopted in 1981, enacted in 1986). HistoryOriginsFollowing on from recognition that women's rights were often marginalised in the context of human rights, a meeting organised by Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF) in March 1995, in Lomé, Togo, called for the development of a specific protocol to the African Charter on Human and People's Rights to address the rights of women. The OAU assembly mandated the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) to develop such a protocol at its 31st Ordinary Session in June 1995, in Addis Ababa.[4] A first draft produced by an expert group of members of the ACHPR, representatives of African NGOs and international observers, organised by the ACHPR in collaboration with the International Commission of Jurists, was submitted to the ACHPR at its 22nd Session in October 1997, and circulated for comments to other NGOs.[4] Revision in co-operation with involved NGOs took place at different sessions from October to January, and in April 1998, the 23rd session of the ACHPR endorsed the appointment of Julienne Ondziel Gnelenga, a Congolese lawyer, as the first Special Rapporteur on Women's Rights in Africa, mandating her to work towards the adoption of the draft protocol on women's rights.[4] The OAU Secretariat received the completed draft in 1999, and in 2000 at Addis Ababa it was merged with the Draft Convention on Traditional Practices in a joint session of the Inter African Committee and the ACHPR.[4] After further work at experts meetings and conferences during 2001, the process stalled and the protocol was not presented at the inaugural summit of the AU in 2002. In early 2003, Equality Now hosted a conference of women's groups, to organise a campaign to lobby the African Union to adopt the protocol, and the protocol's text was brought up to international standards. The lobbying was successful, the African Union resumed the process and the finished document was officially adopted by the section summit of the African Union, on 11 July 2003.[4] ReservationsAt the Maputo Summit, several countries expressed reservations. Tunisia, Sudan, Kenya, Namibia and South Africa recorded reservations about some of the marriage clauses. Egypt, Libya, Sudan, South Africa and Zambia had reservations about "judicial separation, divorce and annulment of marriage". Burundi, Senegal, Sudan, Rwanda and Libya held reservations with Article 14, relating to the "right to health and control of reproduction". Libya expressed reservations about a point relating to conflicts.[2] Ratification processThe protocol was adopted by the African Union on 11 July 2003 at its second summit in Maputo, Mozambique.[5] On 25 November 2005, having been ratified by the required 15 member nations of the African Union, the protocol entered into force.[6] As of September 2023, out of the 55 member countries in the African Union, 49 have signed the protocol and 44 have ratified and deposited the protocol. The AU states that have neither signed nor ratified the Protocol yet are Botswana, Egypt, and Morocco. The states that have signed but not yet ratified are Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, Eritrea, Madagascar, Niger, Somalia, and Sudan.[7] ArticlesThe main articles are:

OppositionThere are two particularly contentious factors driving opposition to the Protocol: its article on reproductive health, which is opposed mainly by Catholics and other Christians, and its articles on female genital mutilation, polygamous marriage and other traditional practices, which are opposed mainly by Muslims. Christian oppositionPope Benedict XVI described the reproductive rights granted to women in the Protocol in 2007 as "an attempt to trivialize abortion surreptitiously".[8] The Roman Catholic bishops of Africa oppose the Maputo Protocol because it defines abortion as a human right. The US-based anti-abortion organisation, Human Life International, describes it as "a Trojan horse for a radical agenda".[9] In Uganda, the powerful Joint Christian Council opposed efforts to ratify the treaty on the grounds that Article 14, in guaranteeing abortion "in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the foetus," is incompatible with traditional Christian morality.[10] In an open letter to the government and people of Uganda in January 2006, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of Uganda set out their opposition to the ratification of the Maputo Protocol.[11] It was nevertheless ratified on 22 July 2010.[12] Muslim oppositionIn Niger, the Parliament voted 42 to 31, with 4 abstentions, against ratifying it in June 2006; in this Muslim-majority country, several traditions banned or deprecated by the Protocol are common.[13] Nigerien Muslim women's groups in 2009 gathered in Niamey to protest what they called "the satanic Maputo protocols", specifying limits to marriage age of girls and abortion as objectionable.[14] In Djibouti, however, the Protocol was ratified in February 2005 after a subregional conference on female genital mutilation called by the Djibouti government and No Peace Without Justice, at which the Djibouti Declaration on female genital mutilation was adopted. The document declares that the Koran does not support female genital mutilation, and on the contrary practising genital mutilation on women goes against the precepts of Islam.[15][16][17] See alsoReferences

External linksWikisource has original text related to this article:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||