|

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

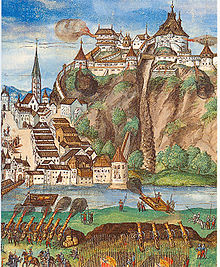

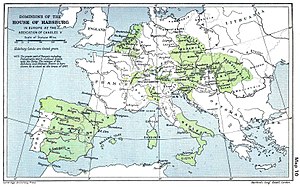

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. He was never crowned by the Pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians.[2] He proclaimed himself elected emperor in 1508 at Trent, with Pope Julius II later recognizing it.[3][4][5] This broke the tradition of requiring a papal coronation for the adoption of the Imperial title. Maximilian was the only surviving son of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, and Eleanor of Portugal. Since his coronation as King of the Romans in 1486, he ran a double government, or Doppelregierung, with his father until Frederick's death in 1493.[6][7] Maximilian expanded the influence of the House of Habsburg through war and his marriage in 1477 to Mary, Duchess of Burgundy. However, he also lost his family's lands in Switzerland to the Swiss Confederacy. Through the marriage of his son Philip the Handsome to eventual queen Joanna of Castile in 1496, Maximilian helped to establish the Habsburg dynasty in Spain, which allowed his grandson Charles to hold the thrones of both Castile and Aragon.[8] Historian Thomas A. Brady Jr. describes him as "the first Holy Roman Emperor in 250 years who ruled as well as reigned" and the "ablest royal warlord of his generation".[9] Nicknamed "Coeur d'acier" ("Heart of steel") by Olivier de la Marche and later historians (either as praise for his courage and soldierly qualities or reproach for his ruthlessness as a warlike ruler),[10][11] Maximilian has entered the public consciousness, at least in the German-speaking world, as "the last knight" (der letzte Ritter), especially since the eponymous poem by Anastasius Grün was published (although the nickname likely existed even in Maximilian's lifetime).[12] Scholarly debates still discuss whether he was truly the last knight (either as an idealized medieval ruler leading people on horseback, or a Don Quixote-type dreamer and misadventurer), or the first Renaissance prince—an amoral Machiavellian politician who carried his family "to the European pinnacle of dynastic power" largely on the back of loans.[13][14] Historians of the late nineteenth century like Leopold von Ranke often criticized Maximilian for putting the interest of his dynasty above that of Germany, hampering the nation's unification process. Since Hermann Wiesflecker's Kaiser Maximilian I. Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit (1971–1986) became the standard work, a more positive image of the emperor has emerged. He is seen as a modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial costs weighed down the Austrians and his military expansion and caused the deaths and sufferings of many people.[11][15][16] Through an "unprecedented" image-building program, with the help of many notable scholars and artists, in his lifetime, the emperor—"the promoter, coordinator, and prime mover, an artistic impresario and entrepreneur with seemingly limitless energy and enthusiasm and an unfailing eye for detail"—had built for himself "a virtual royal self" of a quality that historians call "unmatched" or "hitherto unimagined".[17][18][19][20][21] To this image, new layers have been added by the works of later artists in the centuries following his death, both as continuation of deliberately crafted images developed by his program as well as development of spontaneous sources and exploration of actual historical events, creating what Elaine Tennant dubs the "Maximilian industry".[20][22] Background and childhood Maximilian was born at Wiener Neustadt on 22 March 1459. His father, Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, named him after Maximilian of Tebessa, who Frederick believed had once warned him of imminent peril in a dream. In his infancy, he and his parents were besieged in Vienna by Albert of Austria. One source relates that, during the siege's worst days, he wandered around the castle garrison, begging the servants and men-at-arms for bread.[23] He was the favourite child of his mother, whose personality contrasted his father's. Reportedly she told Maximilian that, "If I had known, my son, that you would become like your father, I would have regretted having born you for the throne." Her early death pushed him even more towards world, where one grew up first as a warrior rather than a politician.[24][25]  Despite the efforts of his father Frederick and his tutor Peter Engelbrecht, whom Maximilian held in contempt, he became an indifferent and belligerent student, who preferred physical activities than learning. Although the two remained on good terms overall, Frederick was horrified by his only surviving son and heir's overzealousness in chivalric contests, extravagance, and heavy tendencies towards wine, feasts and young women, which became evident during their trips in 1473 and 1474. Even though he was very young, the prince's skills and physical attractiveness often made him the center of attention. Although Frederick had forbidden the princes of the Empire from fighting with Maximilian in tournaments, Maximilian gave himself the necessary permission at the first chance he got. Frederick did not allow him to participate in the 1474 war against Burgundy though and placed him under the care of the Bishop of Augsburg instead.[27][28][29] The Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, was the chief political opponent of Maximilian's father Frederick III. Frederick was concerned about Burgundy's expansionist tendencies on the western border of his Holy Roman Empire, and, to forestall military conflict, he attempted to secure the marriage of Charles' daughter, Mary of Burgundy, to Maximilian. After the Siege of Neuss (1474–75), he was successful and secured the marriage.[30] Perhaps as preparation for his task in the Netherlands, in 1476 at the age of 17, Maximilian commanded a military campaign against Hungary. This was the first actual battlefield experience in his life, even though the responsibility was likely shared with more experienced generals.[31][32] The Maximilian and Mary's wedding took place on 19 August 1477.[33] Reign in Burgundy and the Netherlands Maximilian's wife had inherited the large Burgundian domains in France and the Low Countries upon her father's death in the Battle of Nancy on 5 January 1477. The southern part of the Duchy of Burgundy (sometimes called "Burgundy proper") was also claimed by the French crown under Salic law,[35] with Louis XI of France vigorously asserting his claim through military force. Maximilian at once undertook the defence of his wife's dominions. Without support from the Empire and with an empty treasury left by Charles the Bold's campaigns,[36] he carried out a campaign against the French during 1478–1479 and reconquered Le Quesnoy, Conde and Antoing.[37] He defeated the French forces at the Battle of Guinegate, in modern Enguinegatte, on 7 August 1479.[38] Despite winning, Maximilian had to abandon the siege of Thérouanne and disband his army, either because the Netherlanders did not want him to become too strong or because his treasury was empty. The battle was an important landmark in military history though: the Burgundian pikemen were the precursors of the Landsknechte, while the French side derived the momentum for military reform from their loss.[39]  According to some, Maximilian and Mary's wedding contract stipulated that their children would succeed them but that the couple could not be each other's heirs. Mary tried to bypass this rule with a promise to transfer territories as a gift in case of her death, but her plans were confounded. After Mary's death in a riding accident on 27 March 1482 near the Wijnendale Castle, Maximilian's aim was now to secure the inheritance to his and Mary's son, Philip the Handsome.[41] According to Haemers and Sutch, the original marriage contract stipulated that Maximilian could not inherit her Burgundian lands if they had children.[42][43] The Guinegate victory made Maximilian popular, but as an inexperienced ruler, he hurt himself politically by trying to centralize authority without respecting traditional rights and consulting relevant political bodies. The Belgian historian Eugène Duchesne comments that these years were among the saddest and most turbulent in the history of the country, and despite his later great imperial career, Maximilian unfortunately could never compensate for the mistakes he made as regent in this period.[44][45] Some of the Netherlander provinces were hostile to Maximilian, and, in 1482, they signed a treaty with Louis XI in Arras that forced Maximilian to give up Franche-Comté and Artois to the French crown.[35] They openly rebelled twice in the period 1482–1492, attempting to regain the autonomy they had enjoyed under Mary. Flemish rebels managed to capture Philip and even Maximilian himself, but they released Maximilian when Frederick III intervened.[46][47] In 1489, as he turned his attention to his hereditary lands, he left the Low Countries in the hands of Albert of Saxony, who proved to be an excellent choice, as he was less emotionally committed to the Low Countries and more flexible as a politician than Maximilian, while also being a capable general.[48] By 1492, rebellions were completely suppressed. Maximilian revoked the Great Privilege and established a strong ducal monarchy undisturbed by particularism. But he would not reintroduce Charles the Bold's centralizing ordinances. Since 1489 (after his departure), the government under Albert of Saxony had made more efforts in consulting representative institutions and showed more restraint in subjugating recalcitrant territories. Notables who had previously supported rebellions returned to city administrations. The Estates General continued to develop as a regular meeting place of the central government.[49][50] The harsh suppression of the rebellions did have an unifying effect, in that provinces stopped behaving like separate entities each supporting a different lord.[51][52] Helmut Koenigsberger opines that it was not the erratic leadership of Maximilian, who was brave but hardly understood the Netherlands, but the Estates' desire for the survival of the country that made the Burgundian monarchy survive.[53] Jean Berenger and C.A. Simpson argue that Maximilian, as a gifted military champion and organizer, did save the Netherlands from France, although the conflict between the Estates and his personal ambitions caused a catastrophic situation in the short term.[54] Peter Spufford opines that the invasion was prevented by a combination of the Estates and Maximilian, although the cost of war, Maximilian's spendthrift liberality and the interests enforced by his German bankers did cause huge expenditure while income was falling.[55] Jelle Haemers comments that the Estates stopped their support towards the young and ambitious impresario (director) of war because they knew that after Guinegate, the nature of the war was not defensive anymore.[a] Maximilian and his followers had managed to achieve remarkable success in stabilizing the situation though, and a stalemate was kept in Ghent as well as in Bruges, before the tragic death of Mary in 1482 completely turned the political landscape in the whole country upside down.[57] According to Haemers, while Willem Zoete's indictment of Maximilian's government was a one-sided picture that exaggerated the negative points and the Regency Council displayed many of the same problems, Maximilian and his followers could have been more prudent when dealing with the complaints of their opponents before matters became bigger.[58]  During his time in the Low Countries, he had experimented with all kinds of military models available, first urban militia and vassalic troops, then French-style companies that were too rigid and costly, and finally Germanic mercenaries. The brutal efficiency of Germanic mercenaries, together with the financial support of cities outside Flanders like Antwerp, Amsterdam, Mechelen and Brussels as well as a small group of loyal landed nobles proved decisive in the Burgundian-Habsburg regime's final triumph.[58][60][61] Reviewing the French historian Amable Sablon du Corail's La Guerre, le prince et ses sujets. Les finances des Pays-Bas bourguignons sous Marie de Bourgogne et Maximilien d'Autriche (1477–1493), Marc Boone comments that the brutality described shows Maximilian and the Habsburg dynasty's insatiable greed of expansion and inability to adapt to local traditions, while Jean-François Lassalmonie opines that the nation building process (successful, with the establishment of a common tax) was remarkably similar to the same process in France, including the hesitation in working with local levels of the political society, except that the struggle was shorter and after 1494 a peaceful dialogue between the prince and the estates was reached.[61][62] Jelle Haemers suggests that the level of violence associated with the suppression of the revolts as traditionally imagined has been exaggerated and that most of the violence happened in a symbolical manner, but also cautions against the tendency to consider the "central state" in the sense of a modern state.[58][63] While it has been suggested that Maximilian displayed a class-based mentality that favoured the aristocrats,[64] recent studies suggest that, as evidenced by the court ordinance of 1482 among others, he sought to promote "parvenus" who were beholden to himself, and at an alarming speed for the traditional elites.[65][66][67] After the rebellions, concerning the aristocracy, although Maximilian punished few with death, their properties were largely confiscated and they were replaced with a new elite class loyal to the Habsburgs—among whom, there were noblemen who had been part of traditional high nobility but elevated to supranational importance only in this period. The most important of these were John III and Frederik of Egmont, Engelbrecht II of Nassau, Henry of Witthem and the brothers of Glymes–Bergen.[68]  In early 1486, he retook Mortaigne, l'Ecluse, Honnecourt and even Thérouanne, but the same thing like in 1479 happened—he lacked financial resources to exploit and keep his gains. Only in 1492, with a stable internal situation, he was able to reconquer and keep Franche-Comté and Arras on the pretext that the French had repudiated his daughter.[51][73] In 1493, Maximilian and Charles VIII of France signed the Treaty of Senlis, with which Artois and Franche-Comté returned to Burgundian rule while Picardy was confirmed as French possession. The French also continued to keep the Duchy of Burgundy. Thus a large part of the Netherlands (known as the Seventeen Provinces) stayed in the Habsburg patrimony.[35] On 8 January 1488, using a similar 1373 French ordinance as the model, together with Philip, he issued the Ordinance of Admiralty, that organized the Admiralty as a state institution and strove to centralize maritime authority (this was a departure from the policy of Philip the Good, whose 1458 ordinance tried to restore maritime order by decentralizing power).[74][75] This was the beginning of the Dutch navy,[76][77] although initially the policy faced opposition and unfavourable political climate, which only improved with the appointment of Philip of Burgundy-Beveren in 1491.[78] A permanent navy only took shape after 1555 under the governorship of his granddaughter Mary of Hungary.[79] In 1493, Frederick III died, thus Maximilian I became de facto leader of the Holy Roman Empire. He decided to transfer power to the 15-year-old Philip.[80] During the time in the Low Countries, he contracted such emotional problems that except for rare, necessary occasions, he would never return to the land again after gaining control. When the Estates sent a delegation to offer him the regency after Philip's death in 1506, he evaded them for months.[81][82]  As suzerain, Maximilian continued to involve himself with the Low Countries from afar. His son's and daughter's governments tried to maintain a compromise between the states and the Empire.[83] Philip, in particular, sought to maintain an independent Burgundian policy, which sometimes caused disagreements with his father.[84] As Philip preferred to maintain peace and economic development for his land, Maximilian was left fighting Charles of Egmond over Guelders on his own resources. At one point, Philip let French troops supporting Guelders's resistance to his rule pass through his own land.[84] Only at the end of his reign, Philip decided to deal with this threat together with his father.[85] By this time, Guelders had been affected by the continuous state of war and other problems. The duke of Cleves and the bishop of Utrecht, hoping to share spoils, gave Philip aid. Maximilian invested his own son with Guelders and Zutphen. Within months and with his father's skilled use of field artillery, Philip conquered the whole land and Charles of Egmond was forced to prostrate himself in front of Philip. Maximilian would have liked to see the Guelders matter to be dealt with once and for all, but as Charles later escaped and Philip was at haste to make his 1506 fatal journey to Spain, troubles would soon arise again, leaving Margaret to deal with the problems. Maximilian was exasperated by the attitude of Philip (who, in Maximilian's imagination, was probably influenced by insidious French agency) and the Estates, whom he considered to be unbelievably nonchalant and tightfisted about a threat to their own country's security.[86] Philip's death in Burgos was a heavy blow personally (Maximilian's entourage seem to have concealed it from him for more than ten days) and also politically, as by this time, he had become his father's most important international ally, although he retained his independent judgement. All their joint ventures fell apart, including the planned Italian expedition in 1508.[87][88][89]  The Estates preferred to maintain peace with France and Guelders. But Charles of Egmont, the de facto lord of Guelders continued to cause trouble. In 1511, Margaret made an alliance with England and besieged Venlo, but Charles of Egmont invaded Holland so the siege had to be lifted.[90] James D. Tracy opines that Maximilian and Margaret were reasonable in demanding more stern measures against Guelders, but their critics in the Estates General (that had continuously voted against providing funds for wars against Guelders) and among the nobles naively thought that Charles of Egmont could be controlled by maintaining the peaceful relationship with the King of France, his patron. Leading Renaissance humanists in the Netherlands like Erasmus and Hadrianus Barlandus displayed a distrust towards the government and especially the person of Maximilian, whom they believed to be a warlike and greedy prince. After the brutal 1517 campaign of Charles of Egmont in Friesland and Holland, these humanists, in their mistaken belief, spread the stories that the emperor and other princes were concocting clever schemes and creating wars just to expand the Habsburg dominion and extracting money.[91][92][93] By the time Margaret became Regent, Maximilian was less inclined to help regarding the Guelders matter. He suggested to her that the Estates in the Low Countries should defend themselves, forcing her to sign the 1513 treaty with Charles. Habsburg Netherlands would only be able to incorporate Guelders and Zutphen under Charles V.[94][95][96] Following Margaret's strategy of defending the Low Countries with foreign armies, in 1513, at the head of Henry VIII's army, Maximilian gained a victory against the French at the Battle of the Spurs, at little cost to himself or his daughter (in fact according to Margaret, the Low Countries got a profit of one million of gold from supplying the English army).[97][90] For the sake of his grandson Charles's Burgundian lands, he ordered Thérouanne's walls to be demolished (the stronghold had often served as a backdoor for French interference in the Low Countries).[97][98] Reign in the Holy Roman EmpireRecapture of Austria Maximilian was elected King of the Romans on 16 February 1486 in Frankfurt-am-Main and was crowned on 9 April 1486 in Aachen. Much of the Austrian territories and Vienna were under the rule of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, as a result of the Austrian–Hungarian War (1477–1488). Maximilian was now a king without lands. Matthias Corvinus offered Emperor Frederick and his son Maximilian, the return of Austrian provinces and Vienna, if they would renounce the treaty of 1463 and accept Matthias as Frederick's designated heir and favoured successor as Holy Roman Emperor. Before this was settled, Matthias died in Vienna in 1490.[99] However, after Matthias Corvinus' death, civil war broke out in Hungary between the supporters of John Corvinus and the supporters of Vladislaus of Bohemia. Due to the Hungarian civil war, new possibilities were opened for Maximilan. In July 1490, Maximilian began a series of short sieges that reconquered cities and fortresses that his father had lost in Austria. Maximilian entered Vienna, already evacuated by the Hungarians, in August 1490. He was injured while attacking the citadel guarded by a garrison of 400 Hungarians troops who repelled his forces twice, but after a few days they surrendered.[100][101] In addition, the County of Tyrol and Duchy of Bavaria went to war in the late 15th century. Bavaria demanded money from Tyrol that had been loaned on the collateral of Tyrolean lands. In 1490, the two states demanded that Maximilian I step in to mediate the dispute. His Habsburg cousin, the childless Archduke Sigismund, was negotiating to sell Tyrol to their Wittelsbach rivals rather than let Emperor Frederick inherit it. Maximilian's mediation led to a reconciliation and a reunited dynastic rule in the 1490.[102] Because Tyrol had no law code at this time, the nobility freely expropriated money from the populace, which caused the court in Innsbruck to fester with corruption. After taking control, Maximilian instituted immediate financial reform. Gaining control of Tyrol for the Habsburgs was of strategic importance because it linked the Swiss Confederacy to the Habsburg-controlled Austrian lands, which facilitated some imperial geographic continuity. From 1497 to 1498, Maximilian negotiated an inheritance contract with the last Meinhardin prince, Count Leonhard of Gorizia, which was intended to bring the County of Gorizia to the Habsburgs. However, it was only after a dispute with the Republic of Venice that the Gorizia stadtholder, Virgil von Graben, finally succeeded in realizing this contract.[103] Expedition in HungaryBeatrice of Naples, Matthias Corvinus's widow, initially supported Maximilian out of hope that he would marry her, but Maximilian did not want this.[104] The Hungarian magnates found Maximilian impressive, but they wanted a king they could dominate. The crown of Hungary thus fell to King Vladislaus II, who was deemed weaker in personality and also agreed to marry Beatrice.[105][106][107] Tamás Bakócz, the Hungarian chancellor, allied himself with Maximilian and helped him to circumvent the 1505 Diet which declared that no foreigner could be elected as King of Hungary.[108] With money from Innsbruck and southern German towns, he raised enough cavalry and Landsknechte to campaign into Hungary. Despite Hungary's gentry's hostility to the Habsburg, he managed to gain many supporters from higher aristocracy, including several of Corvinus's supporters. One of them, Jakob Székely, handed over Styrian castles to him.[109] He claimed his status as King of Hungary. In the meantime, Vladislas was proclaimed King of Hungary on July 15, 1490, and was crowned at Székesfehérvár in September. Maximilian responded with great force, using a massive grant of funds from the Tyrolean Estates to invade Hungary with an army of around 17,000 men. Crossing the Raab River in late October, Maximilian encountered little resistance in Hungary, as the unprepared Vladislas was not inclined towards action. Maximilian was joined by numerous Hungarian nobles and even magnates. Despite stiff resistance, the city was bombarded, and eventually captured. This resulted in looting and slaughter that Maximilian and his officers were unable to prevent. The next day became a turning point in the campaign, as his mercenaries mutinied due to the prohibition of looting.[110] Faced with a severe winter, his troops refused to continue fighting, requesting Maximilian to double their pay, which he could not afford. The revolt turned the situation in favour of the Jagiellonian forces[105] and Maximilian was forced to return. He depended on his father and the territorial estates for financial support. Soon he reconquered Lower and Inner Austria for his father, who returned and settled at Linz. Worrying about his son's adventurous tendencies, Frederick decided to starve him financially.   In 1491, they signed the Peace of Pressburg, which provided that Maximilian recognized Vladislaus as King of Hungary, but the Habsburgs would inherit the throne on the extinction of Vladislaus's male line and the Austrians also received 100,000 golden florins as war reparations.[112] It was Maximilian that the Croatians began to harbour a connection with. However, the Croatian nobility wanted him as King. Worrying that a multi-fronted war would leave him overextended , Maximilian evacuated from Croatia and accepted the treaty with the Jagiellons.[113][114][115] Italian and Swiss wars As the Treaty of Senlis had resolved French differences with the Holy Roman Empire, King Louis XII of France had secured borders in the north and turned his attention to Italy, where he made claims to the Duchy of Milan. In 1499 and 1500 he conquered it and drove Lodovico il Moro into exile.[116] This brought him into a potential conflict with Maximilian, who on 16 March 1494 had married Bianca Maria Sforza, a daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, duke of Milan.[35][116] However, Maximilian was unable to prevent Louis from capturing Milan.[116] The Italian Wars resulted[35] in Maximilian joining the Holy League to counter the French. His campaigns in Italy generally went poorly, and his progress was quickly stopped. Maximilian's campaigns tend to be criticized for being wasteful and gaining him little. Despite his work in enhancing his army, due to financial difficulties, the forces he could muster were too small to make a difference.[117][118] In Italy, he gained the nickname of "Massimiliano di pochi denari" (Maximilian the Moneyless).[119] One particularly humiliating campaign occurred in 1508, with a force mustered from hereditary lands and with limited resources, he decided to attack Venice. The force under Sixt Trautson were routed by Bartolomeo d'Alviano, while Maximilian's advance was blocked by the Venetian force under Niccolò di Pitigliano and a French army under Alessandro Trivulzio. Bartolomeo d'Alviano then pushed into the Imperial territory, seizing Gorizia and Trieste, and forcing Maximilian to sign a very unfavourable truce.[120] Afterwards, he formed the League of Cambrai with Spain, France and Pope Julius II and won back territories he had conceded and some Venetian land. Most of the Slovenian areas were transferred to the Habsburgs. But atrocities and expenses for war devastated Austria and Carniola.[121] Lack of financial means meant that he depended on allies' resources.[54][122][123] When Schiner suggested they should let war feed war, he did not agree and was not brutal enough to do that.[124] He acknowledged French control of Milan in 1515.[125] The situation in Italy wasn't the only problem Maximilian had then. The Swiss won a decisive victory against the Empire at Dornach on 22 July 1499. Maximilian had no choice but to agree to a peace treaty signed on 22 September 1499 in Basel that granted the Swiss Confederacy independence. Jewish and Romani policies Jewish policy under Maximilian fluctuated greatly, usually influenced by financial considerations and the emperor's vacillating attitude when facing opposing views. In 1496, Maximilian issued a decree which expelled all Jews from Styria and Wiener Neustadt.[126] Between 1494 and 1510, he authorized thirteen expulsions of Jews in return for fiscal compensations from local government.[127][128] After 1510, this happened only once, and he showed resistance in a campaign to expel Jews from Regensburg. David Price comments that during the first seventeen years of his reign, he was a great threat to the Jews, but after 1510, even if his attitude was still exploitative, his policy gradually changed. A factor that probably played a role in the change was Maximilian's success in expanding imperial taxing over German Jewry, at this point, he likely considered the possibility of generating taxes from stable Jewish communities, instead of temporary compensations from local jurisdictions.[129] Noflatscher and Péterfi note that Maximilian had a deep dislike for Jews since childhood, the reason of which is unknown, since both of his parents greatly favoured the Jews.[130] In 1509, relying on the influence of Kunigunde, Maximilian's pious sister and the Cologne Dominicans, the anti-Jewish agitator Johannes Pfefferkorn was authorized by Maximilian to confiscate all offending Jewish books, except the Bible. The confiscations happened in Frankfurt, Bingen, Mainz and other German cities. Responding to the order, the archbishop of Mainz, the city council of Frankfurt and various German princes tried to intervene in defense of the Jews. Maximilian consequently ordered the confiscated books to be returned. On 23 May 1510 though, influenced by a supposed "host desecration" and blood libel in Brandenburg, as well as pressure from Kunigunde, he ordered the creation of an investigating commission and asked for expert opinions from German universities and scholars. The prominent humanist Johann Reuchlin argued strongly in defense of the Jewish books, especially the Talmud.[131] Reuchlin's arguments seemed to leave an impression on the emperor,[132] who gradually developed an intellectual interest in the Talmud and other Jewish books. Maximilian later urged the Hebraist Petrus Galatinus to defend Reuchlin's position. Galatinus dedicated his work De Arcanis Catholicae Veritatis, which provided 'a literary "threshold" where Jews and gentiles might meet', to the emperor.[133][134] It was Maximilian's support that enabled Reuchlin to fully devote himself to Jewish literature. Like his father Frederick III and his grandson Ferdinand I, he held Jewish physicians and teachers in high esteem.[135] In 1514, he appointed Paulus Ricius, a Jew who converted to Christianity, as his personal physician. He was more interested in Ricius's Hebrew skills than in his medical abilities though. In 1515, he reminded his treasurer Jakob Villinger that Ricius was admitted for the purpose of translating the Talmud into Latin, and urged Villinger to keep an eye on him. Perhaps overwhelmed by the emperor's request, Ricius only managed to translate two out of sixty-three Mishna tractates before the emperor's death.[136] Ricius managed to publish a translation of Joseph Gikatilla's Kabbalistic work The Gates of Light, which was dedicated to Maximilian, though.[137] It was under Frederick and Maximilian that the foundation of Modern Judaism arose, steeped in Humanism.[135] It was under Maximilian that policies concerning the Romani became harsher. In 1500, a notice was given to the Romani that they had to leave Germany by the next Easter, or become outlaws (the Romani had to evade the law by following a constant circuit from an area to another, and at times, obtain patronage from aristocrats). The Reformation beginning in 1517 did not consider them foreigners anymore,[citation needed] but as local beggars, they also faced discrimination. The change in policy was seemingly linked to the fear of the Turks (the Romani were accused of being spies for the Turks). Kenrich and Puxon explains that connect the situation with the consolidation of European nation-states, that also stimulated similar policies elsewhere.[138][139] Reforms Within the Holy Roman Empire, there was consensus that reforms were needed to preserve the unity of the Empire.[142] For most of his reign, Frederick III had considered reform as a threat to his imperial prerogatives and wanted to avoid confrontations on the matter. However, in his last years, mainly to secure election for Maximilian, he presided over the initial phase of reform. Maximilian was more open to reform. From 1488 through his reign as sole ruler, he practiced a policy of brokerage, acting as the impartial judge between options suggested by the princes.[143][144] Many measures were launched in the 1495 Reichstag at Worms. A new court was introduced, the Reichskammergericht, that was largely independent from the Emperor. A new tax was launched to finance the Empire's affairs, the Gemeine Pfennig.[142][145][146][147] It was levied for the first time between 1495 and 1499, raising 136,000 florins, and another five times during the 1512–1551 period, before being supplanted by the matricular system which allowed common burdens to be assessed at imperial as well as Kreis level.[148] To create a rival for the Reichskammergericht, Maximilian established the Reichshofrat, which had its seat in Vienna. Unlike the Reichskammergericht, the Reichshofrat looked into criminal matters and even allowed the emperors the means to depose rulers who did not live up to expectations. Pavlac and Lott note that, during Maximilian's reign, this council was not popular though.[149] According to Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger though, throughout the early modern period, the Reichshofrat remained the faster and more efficient among the two Courts. The Reichskammergericht on the other hand was often torn by matters related to confessional alliance.[150] Around 1497–1498, as part of his administrative reforms, he restructured his Privy Council (Geheimer Rat), a decision which today induces much scholarly discussion. Apart from balancing the Reichskammergericht with the Reichshofrat, this act of restructuring seemed to suggest that, as Westphal quoting Ortlieb, the "imperial ruler—independent of the existence of a supreme court—remained the contact person for hard pressed subjects in legal disputes as well, so that a special agency to deal with these matters could appear sensible".[151] In 1500, as Maximilian urgently needed assistance for his military plans, he agreed to establish an organ called the Reichsregiment (central imperial government, consisting of twenty members including the Electors, with the Emperor or his representative as its chairman), first organized in 1501 in Nuremberg and consisted of the deputies of the Emperor, local rulers, commoners, and the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. Maximilian resented the new organization as it weakened his powers, and the Estates failed to support it. The new organ proved politically weak, and its power returned to Maximilian in 1502.[116][152][153] According to Thomas Brady Jr. and Jan-Dirk Müller, the most important governmental changes targeted the chancery. Early in Maximilian's reign, the Court Chancery at Innsbruck competed with the Imperial Chancery. By referring the political matters in Tyrol as well as Imperial problems to the Court Chancery, Maximilian gradually centralized its authority. The two chanceries became combined in 1502.[141] Jan-Dirk Müller opines that this chancery became the decisive government institution since 1502. In 1496, the emperor created a general treasury (Hofkammer) in Innsbruck, which became responsible for all the hereditary lands. The chamber of accounts (Raitkammer) at Vienna was made subordinate to this body.[154] Under Paul von Liechtenstein, the Hofkammer was entrusted with not only hereditary lands' affairs, but Maximilian's affairs as the German king too.[155] Historian Joachim Whaley points out that there are usually two opposite views on Maximilian's rulership: one side is represented by the works of nineteenth century historians like Heinrich Ullmann or Leopold von Ranke, which criticize him for selfishly exploiting the German nation and putting the interest of his dynasty over his Germanic nation, thus impeding the unification process; the more recent side is represented by Hermann Wiesflecker's biography of 1971–86, which praises him for being "a talented and successful ruler, notable not only for his Realpolitik but also for his cultural activities generally and for his literary and artistic patronage in particular".[156][157]  According to Brady Jr., Ranke is right regarding the fact Berthold von Henneberg and other princes did play the leading role in presenting the proposals for creating institutions (that would also place the power in the hands of the princes) in 1495. However, what Maximilian opposed was not reform per se. He generally shared their sentiments regarding ending feuds, sounder administrative procedures, better record-keeping, qualifications for offices etc. Responding to the proposal that an Imperial Council (the later Reichsregiment) should be created, he agreed and welcomed the participation of the Estates, but he alone should be the one who appointed members and the council should function only during his campaigns. He supported modernizing reforms (which he himself pioneered in his Austrian lands), but also wanted to tie it to his personal control, above all by permanent taxation, which the Estates consistently opposed. In 1504, when he was strong enough to propose his own ideas of such a Council, the cowered Estates tried to resist.[158] At his strongest point though, he still failed to find a solution for the common tax matter, which led to disasters in Italy later.[158] Stollberg-Rilinger notes that had the Common Penny been successful, modern governmental structures would likely emerge on the Empire's level, but that was why it failed as it was not in the interest of territorial lords.[159] Meanwhile, he explored Austria's potential as a base for Imperial power and built his government largely with officials drawn from the lower aristocracy and burghers in Southern Germany.[158] Whaley notes that the real foundation of his Imperial power lay with his networks of allies and clients, especially the less powerful Estates, who helped him to recover his strength in 1502—his first reform proposals as King of the Romans in 1486 were about the creation of a network of regional unions. According to Whaley, "More systematically than any predecessor, Maximilian exploited the potential of regional leagues and unions to extend imperial influence and to create the possibility of imperial government in the Reich." To the Empire, the mechanisms involving such regional institutions bolstered the Land Piece (Ewiger Landfriede) declared in 1495 as well as the creation of the Reichskreise (Imperial Circles, which would serve the purpose of organize imperial armies, collect taxes and enforce orders of the imperial institutions: there were six at first; in 1512, the number increased to ten),[160][161] between 1500 and 1512, although they were only fully functional some decades later.[162] While Brady describes Maximilian's thinking as "dynastic and early modern", Heinz Angermeier (also focusing on his intentions at the 1495 Diet) writes that for Maximilian, "the first politician on the German throne", dynastic interests and imperial politics had no contradiction. Rather, the alliance with Spain, imperial prerogatives, anti-Ottoman agenda, European leadership and inner politics were all tied together.[158][163] In Austria, Maximilian defined two administrative units: Lower Austria and Upper Austria (Further Austria was included in Upper Austria).[164]  Another development arising from the reform was that, amidst the prolonged struggles between the monarchical-centralism of the emperor and the estates-based federalism of the princes, the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) became the all-important political forum and the supreme legal and constitutional institution (without any declared legal basis or inaugural act), which would act as a guarantee for the preservation of the Empire in the long run.[166][167] Ultimately, the results of the reform movement presided over by Maximilian, as presented in the shape of newly formed structures as well as the general framework (functioning as a constitutional framework), were a compromise between emperor and estates, who more or less shared common cause but separate interests. Although the system of institutions that arose from this was not complete, a flexible, adaptive problem-solving mechanism for the Empire was formed.[168][169][170] Stollberg also links the development of the reform to the concentration of supranational power in the Habsburgs' hand, which manifested in the successful dynastic marriages of Maximilian and his descendants (and the successful defense of those lands, notably the rich Low Countries) as well as Maximilian's development of a revolutionary post system that helped the Habsburgs to maintain control of their territories (Additionally, the communication revolution created by the combination of the postal system with printing would boost the empire's capability of disseminating orders and policies as well as its coherence in general, elevating cultural life, and also help reformers like Luther to broadcast their views effectively.).[171][172][173] Recent German research explores the importance of the Reichstags that followed the 1495 one in Worms. The 1512 Reichstag in Trier that Maximilian assembled, for example, was decisive for the development of the Reichskammergericht, the Land Peace and the Gemeine Pfennig, although by this point it was clear that Maximilian was already past his best years (the early signs of crisis seemed to have showed already in Cologne, 1505)—which, according to Dietmar Heil, resulted in the fact that the Gemeine Pfennig was only partially approved and then partially implemented.[174][175] Seyboth notes that, in his later years, he became more irritable, obstinate and closed, which led to growing alienation with the Estates. He recognized the trend of the Reichstag to become a more modern institution, the concern of the Estates with internal problems, and contributed to the solutions, but only so that his own interests will not be ignored.[176] According to Whaley, if Maximilian ever saw Germany as a source of income and soldiers only, he failed miserably in extracting both. His hereditary lands and other sources always contributed much more (the Estates gave him the equivalent of 50,000 gulden per year, a lower than even the taxes paid by Jews in both the Reich and hereditary lands, while Austria contributed 500,000 to 1 million gulden per year). On the other hand, the attempts he demonstrated in building the imperial system alone shows that he did consider the German lands "a real sphere of government in which aspirations to royal rule were actively and purposefully pursued." Whaley notes that, despite struggles, what emerged at the end of Maximilian's rule was a strengthened monarchy and not an oligarchy of princes. If he was usually weak when trying to act as a monarch and using imperial instituations like the Reichstag, Maximilian's position was often strong when acting as a neutral overlord and relying on regional leagues of weaker principalities such as the Swabian league, as shown in his ability to call on money and soldiers to mediate the Bavaria dispute in 1504, after which he gained significant territories in Alsace, Swabia and Tyrol. His fiscal reform in his hereditary lands provided a model for other German princes.[177] Benjamin Curtis suggests that while Maximilian was not able to fully create a common government for his lands (although the chancellery and court council were able to coordinate affairs across the realms), he strengthened key administrative functions in Austria and created central offices to deal with financial, political and judicial matters—these offices replaced the feudal system and became representative of a more modern system that was administered by professionalized officials. After two decades of reforms, the emperor retained his position as first among equals, while the empire gained common institutions through which the emperor shared power with the estates.[178] Dietmar Heil argues that the Estates actually offered Maximilian considerable financial help, in consideration of their financial capacity. According to Heil, historians have traditionally been too receptive to the statements of the deceptive emperor (who tried to create such an impression in order to generate motivation).[179] In 1508, Maximilian, with the assent of Pope Julius II, took the title Erwählter Römischer Kaiser ("Elected Roman Emperor"), thus ending the centuries-old custom that the Holy Roman Emperor had to be crowned by the Pope.  At the 1495 Diet of Worms, the Reception of Roman Law was accelerated and formalized. The Roman Law was made binding in German courts, except in the case it was contrary to local statutes.[182] In practice, it became the basic law throughout Germany, displacing Germanic local law to a large extent, although Germanic law was still operative at the lower courts.[183][184][185][186] Other than the desire to achieve legal unity and other factors, the adoption also highlighted the continuity between the Ancient Roman empire and the Holy Roman Empire.[187] To realize his resolve to reform and unify the legal system, the emperor frequently intervened personally in matters of local legal matters, overriding local charters and customs. This practice was often met with irony and scorn from local councils, who wanted to protect local codes.[188] Maximilian had a general reputation of justice and clemency, but could occasionally act in a violent and resentful manner if personally affronted.[189][190][191][192]  In 1499, as the ruler of Tyrol, he introduced the Maximilianische Halsgerichtsordnung (the Penal Code of Maximilian). This was the first codified penal law in the German speaking world. The law attempted to introduce regularity into contemporary discrete practices of the courts. This would be part of the basis for the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina established under Charles V in 1530.[194][195] Regarding the use of torture, the court needed to decide whether someone should be tortured. If such a decision was made, three council members and a clerk should be present and observe whether a confession was made only because of the fear of torture or the pain of torture, or that another person would be harmed.[196] During the Austrian-Hungarian war (1477–1488), Maximilian's father Frederick III issued the first modern regulations to strengthen military discipline. In 1508, using this ordinance as the basis, Maximilian devised the first military code ("Articles"). This code included 23 articles. The first five articles prescribed total obedience to imperial authority. Article 7 established the rules of conduct in camps. Article 13 exempted churches from billeting while Article 14 forbade violence against civilians: "You shall swear that you will not harm any pregnant women, widows and orphans, priests, honest maidens and mothers, under the fear of punishment for perjury and death". These actions that indicated the early developments of a "military revolution" in European laws had a tradition in the Roman concept of a just war and ideas of sixteenth-century scholars, who developed this ancient doctrine with a main thesis which advocated that war was a matter between two armies and thus the civilians (especially women, children and old people) should be given immunity. The code would be the basis for further ordinances by Charles V and new "Articles" by Maximilian II, which became the universal military code for the whole Holy Roman Empire until 1642.[197] The legal reform seriously weakened the ancient Vehmic court (Vehmgericht, or Secret Tribunal of Westphalia, traditionally held to be instituted by Charlemagne but this theory is now considered unlikely),[198][199] although it would not be abolished completely until 1811 (when it was abolished under the order of Jérôme Bonaparte).[200][201] In 1518, after a general diet of all Habsburg hereditary lands, the emperor issued the Innsbrucker Libell which set out the general defence order (Verteidigungsordnung) of Austrian provinces, which "gathered together all the elements that had appeared and developed over the preceding centuries.". The provincial army, based on noble cavalry, was for defence only; bonded labourers were conscripted using a proportional conscription system; upper and lower Austrian provinces agreed on a mutual defence pact in which they would form a joint command structure if either were attacked. The military system and other reforms were threatened after Maximilian's deạth but would be restored and reorganized later under Ferdinand I.[202] According to Brady Jr., Maximilian was no reformer of the church though. Personally pious, he was also a practical caesaropapist who was only interested in the ecclesiastical organization as far as reforms could bring him political and fiscal advantages.[203] He met Luther once at the Diet of Augsburg in 1518, "a rehearsal for Worms in 1521". He saw the grievances and agreed with Luther on some points. However as the religious question was a matter of money and power to him, he had no interest in stopping the indulgences. At this point, he was too busy with his grandson's election. As Luther was about to be arrested by the papal legate, he granted him a letter of safe passage. Brady notes that blindness to the need to reform from above would lead to the reform from below.[204][205] Finance and Economy Maximilian was always troubled by financial shortcomings; his income never seemed to be enough to sustain his large-scale goals and policies. For this reason he was forced to take substantial credits from Upper German banker families, especially from the Gossembrot, Baumgarten, Fugger, and Welser families.[206] Jörg Baumgarten even served as Maximilian's financial advisor. The connection between the emperor and banking families in Augsburg was so widely known that Francis I of France derisively nicknamed him "the Mayor of Augsburg" (another story recounts that a French courtier called him the alderman of Augsburg, to which Louis XII replied: "Yes, but every time that this alderman rings the tocsin from his belfry, he makes all France tremble.", referring to Maximilian's military ability).[207][208] Around 70 percent of his income went to wars (and by the 1510s, he was waging wars on almost all sides of his border).[209][210] At the end of Maximilian's rule, the Habsburgs' mountain of debt totalled six million gulden to six and a half million gulden, depending on the sources. By 1531, the remaining amount of debt was estimated at 400,000 gulden (about 282,669 Spanish ducats).[211] In his entire reign, he had spent around 25 million gulden, much of which was contributed by his most loyal subjects—the Tyrolers. The historian Thomas Brady comments: "The best that can be said of his financial practices is that he borrowed democratically from rich and poor alike and defaulted with the same even-handedness".[212] By comparison, when he abdicated in 1556, Charles V left Philip a total debt of 36 million ducats (equal to the income from Spanish America for his entire reign), while Ferdinand I left a debt of 12.5 million gulden when he died in 1564.[213][214][215][216] Economy and economic policies under the reign of Maximilian is a relatively unexplored topic, according to Benecke.[217]  Overall, according to Whaley, "The reign of Maximilian I saw recovery and growth but also growing tension. This created both winners and losers.", although Whaley opines that this is no reason to expect a revolutionary explosion (in connection to Luther and the Reformation).[218] Whaley points out, though, that because Maximilian and Charles V tried to promoted the interests of the Netherlands, after 1500, the Hanseatic League was negatively affected and their growth relative to England and the Netherlands declined.[b] In the Low Countries, during his regency, to get more money to pay for his campaigns, he resorted to debase coins in the Burgundian mints, causing more conflicts with the interests of the Estates and the merchant class.[219][220][221] In Austria, although this was never enough for his needs, his management of mines and salt works proved efficient, with a marked increase in revenue, the fine silver production in Schwaz increased from 2,800 kg in 1470 to 14,000 kg in 1516. Benecke remarks that Maximilian was a ruthless, exploitative businessman while Hollegger sees him as a clearheaded manager with sober cost-benefit analysis.[222][223] Ultimately, he had to mortgage these properties to the Fuggers to get quick cash. The financial price would ultimately fall on the Austrian population. Fichtner states that Maximilian's pan-European vision was very expensive, and his financial practices antagonized his subjects both high and low in Burgundy, Austria and Germany (who tried to temper his ambitions, although they never came to hate the charismatic ruler personally), this was still modest in comparison with what was about to come, and the Ottoman threat gave the Austrians a reason to pay.[224][225] For both economic and military purposes, he encouraged the mining of copper, silver and calamine, coining, brass manufacturing and the arms industry. He took pains to protect the local economy, especially in Tyrol, where there was a mining boom (accompanied by a population boom), although Safley notes that he also enabled families like the Hochstetters to exploit the economy for their own ends. Agriculture also developed significantly, except in Lower Austria which suffered from the war with Matthias Corvinus.[226][227][228] Augsburg benefitted majorly from the establishment and expansion of the Kaiserliche Reichspost as well as Maximilian's personal attachment to the city. The imperial city became "the dominant centre of early capitalism" of the 16th century, and "the location of the most important post office within the Holy Roman Empire". From Maximilian's time, as the "terminuses of the first transcontinental post lines" began to shift from Innsbruck to Venice and from Brussels to Antwerp, in these cities, the communication system and the news market started to converge. As the Fuggers as well as other trading companies based their most important branches in these cities, these traders gained access to these systems as well. (Despite a widely circulated theory which holds that the Fuggers themselves operated their own communication system, in reality they relied upon the imperial posts, presumably from the 1490s onwards, as official members of the court of Maximilian I).[229] Leipzig started its rise into one of the largest European trade fair cities after Maximilian granted them wide-ranged privileges in 1497 (and raised their three markets to the status of Imperial Fair in 1507).[230][231] Tu felix Austria nubeBackgroundTraditionally, German dynasties had exploited the potential of the imperial title to bring Eastern Europe into the fold, in addition to their lands north and south of the Alps. Under Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, the House of Luxembourg, predecessors of the Habsburgs as the Imperial dynasty, had managed to gain an empire almost comparable in scale to the later Habsburg empire, although at the same time they lost the Kingdom of Burgundy and control over Italian territories. Their focus on the East, especially Hungary (which was outside the Holy Roman Empire and also gained by the Luxembourgs with a marriage), allowed the new Burgundian rulers from the House of Valois to foster discontent among German princes. Thus, the Habsburgs were forced to refocus their attention on the West. Frederick III's cousin and predecessor, Albert II (who was Sigismund's son-in-law and heir through his marriage with Elizabeth of Luxembourg) had managed to combine the crowns of Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia under his rule, but he died young.[232][233][234] During his rule, Maximilian had a double focus on both the East and the West. The successful expansion (with the notable role of marriage policy) under Maximilian bolstered his position in the Empire, and also created more pressure for an imperial reform, so that they could get more resources and coordinated help from the German territories to defend their realms and counter hostile powers such as France.[235][236] Marriage and foreign policy under Maximilian  As part of the Treaty of Arras, Maximilian betrothed his three-year-old daughter Margaret to the Dauphin of France (later Charles VIII), son of his adversary Louis XI.[238][239] The betrothal was the result of clandestine negotiations between Louis XI and Ghent—as Maximilian's position was temporarily weakened by his wife's death, he had no say in the matter.[240] Dying shortly after signing the Treaty of Le Verger, Francis II, Duke of Brittany, left his realm to his daughter Anne. In search of alliances to protect her domain from neighboring interests, she betrothed herself to Maximilian I in 1490. About a year later, they married by proxy.[241][242][243] However, Charles VIII and his sister Anne wanted her inheritance for France. So, when the former came of age in 1491, and taking advantage of Maximilian and his father's interest in the succession of their adversary Mathias Corvinus, King of Hungary,[244] Charles repudiated his betrothal to Margaret, invaded Brittany, forced Anne of Brittany to repudiate her unconsummated marriage to Maximilian, and married her himself.[245][246][247] Margaret then remained in France as a hostage of sorts until 1493, when she was finally returned to her father with the signing of the Treaty of Senlis.[248][249] In the same year, as the hostilities of the lengthy Italian Wars with France were in preparation,[250] Maximilian contracted another marriage for himself, this time to Bianca Maria Sforza, daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, with the intercession of his brother, Ludovico Sforza,[251][252][253][254] then regent of the duchy after the former's death.[255] In the East, Maximilian faced the need to reduce the growing pressures on the Empire brought about by treaties between the rulers of France, Poland, Hungary, Bohemia, and Russia, as well as to bolster his dynasty's position—temporarily threatened by the union between Anne of Foix-Candale and Vladislaus II of Hungary, in addition to resistance of the Hungarian magnates—in Bohemia and Hungary (that the Habsburgs claimed through inheritance and overlordship). Maximilian met with the Jagiellonian kings Ladislaus II of Hungary and Bohemia and Sigismund I of Poland at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515. There they arranged for Maximilian's granddaughter Mary to marry Louis, the son of Ladislaus, and for Anne (the sister of Louis) to marry Maximilian's grandson Ferdinand (both grandchildren being the children of Philip the Handsome, Maximilian's son, and Joanna of Castile).[256][257][258] The marriages arranged there brought Habsburg kingship over Hungary and Bohemia in 1526.[259][260] In 1515, Louis was adopted by Maximilian.[261] Maximilian had to serve as the proxy groom to Anna in the betrothal ceremony, because only in 1516 did Ferdinand agree to enter into the marriage, which would happen in 1521.[262]  These political marriages were summed up in the following Latin elegiac couplet, reportedly spoken by Matthias Corvinus: Bella gerant aliī, tū fēlix Austria nūbe/ Nam quae Mars aliīs, dat tibi regna Venus, "Let others wage war, but thou, O happy Austria, marry; for those kingdoms which Mars gives to others, Venus gives to thee."[263][264] Contrary to the implication of this motto though, Maximilian waged war aplenty (In four decades of ruling, he waged 27 wars in total).[265] Late in his life though, only the military situation in the East worked well—the Magyars was said to fear him more than the Turks or the Devil. In the West, he could do no more than blocking French expansion and only with Spanish aid.[118] His general strategy was to combine his intricate systems of alliance, military threats and offers of marriage to realize his expansionist ambitions. Using overtures to Russia, Maximilian succeeded in coercing Bohemia, Hungary and Poland into acquiesce in the Habsburgs' expansionist plans. Combining this tactic with military threats, he was able to gain the favourable marriage arrangements In Hungary and Bohemia (which were under the same dynasty).[266] According to Bence Péterfi, many Hungarian nobles maintained dual loyalty to both the Habsburgs and the Jagiellons. After the Peace of Pressburg (1491) legalized this phenomenon, there was a change in dynamic: "While at the time of the conflicts between Frederick III and Matthias Corvinus it was primarily those who took the side of the Hungarian king who were able to pursue successful careers, after 1491, the situation reversed, and those who were on the side of the Habsburgs seemed to have more opportunities."[267] At the same time, his sprawling panoply of territories as well as potential claims constituted a threat to France, thus forcing Maximilian to continuously launch wars in defense of his possessions in Burgundy, the Low Countries and Italy against four generations of French kings (Louis XI, Charles VIII, Louis XII, Francis I). Coalitions he assembled for this purpose sometimes consisted of non-imperial actors like England. Edward J. Watts comments that the nature of these wars was dynastic, rather than imperial.[268] Fortune was also a factor that helped to bring about the results of his marriage plans. The double marriage could have given the Jagiellon a claim in Austria, while a potential male child of Margaret and John, a prince of Spain, would have had a claim to a portion of the maternal grandfather's possessions as well. But as it turned out, Vladislaus's male line became extinct, while the frail John died without offspring, so Maximilian's male line was able to claim the thrones.[269] Death and succession  During his last years, Maximilian began to focus on the question of his succession.[270] His goal was to secure the throne for Charles. According to the traditional view, a credit of one million gulden was provided (to Charles, after Maximilian's death, according to Wiesflecker and Koenigsberger) by the Fuggers (the Cortes had voted over 600,000 crowns for Charles's election campaign, but money from Spain could not arrive quick enough), which was used for advertising and to bribe the prince-electors, and that this was the decisive factor in Charles's successful election.[271][272][273][274] Others point out that while the electors were paid, this was not the reason for the outcome, or at most played only a small part.[275] The important factor that swayed the final decision was that Frederick refused the offer, and made a speech in support of Charles on the ground that they needed a strong leader against the Ottomans, Charles had the resources and was a prince of German extraction.[276][277][278][279] The death of Maximilian in 1519 seemed to put the succession at risk, but in a few months the election of Charles V was secured.[116] In 1501, Maximilian fell from his horse and badly injured his leg, causing him pain for the rest of his life. Some historians have suggested that Maximilian was "morbidly" depressed: from 1514, he travelled everywhere with his coffin.[280][281] In 1518, feeling his death near after seeing an eclipse, he returned to his beloved Innsbruck, but the city's innskeepers and purveyors did not grant the emperor's entourage further credit. The resulting fit led to a stroke that left him bedridden on 15 December 1518. However, he continued to read documents and received foreign envoys right until the end. Maximilian died in Wels, Upper Austria, at three o'clock in the morning on 12 January 1519.[282][283][284] Different historians have listed different diseases as the main cause of death, including cancer (likely stomach cancer or intestinal cancer), pneumonia, syphilis, gall stones, stroke (he did have a combination of dangerous medical problems) etc.[282][283][285][286] Maximilian was succeeded as Emperor by his grandson Charles V, his son Philip the Handsome having died in 1506. For penitential reasons, Maximilian gave very specific instructions for the treatment of his body after death. He wanted his hair to be cut off and his teeth knocked out, and the body was to be whipped and covered with lime and ash, wrapped in linen, and "publicly displayed to show the perishableness of all earthly glory".[287] Gregor Reisch, the emperor's friend and confessor who closed his eyes, did not obey the instruction though. He placed a rosary in Maximilian's hand and other sacred objects near the corpse.[288][289] He was buried in the Castle Chapel at Wiener Neustadt on borrowed money.[282] The casket was opened during renovation under Maria Theresa. After that, the body was reinterred in a Baroque sarcophagus, that later was found unscathed amidst the wreckage of the chapel (due to the Second World War) on 6 August 1946. The emperor was ceremoniously buried again in 1950.[290] LegacyAncestry

Official style

We, Maximilian, by the Grace of God, elected Roman Emperor, always Augmenter of the Empire, King of Hungary, Dalmatia, Croatia, etc. Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Brittany, Lorrain, Brabant, Stiria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limbourg, Luxembourg, and Guelders; Count of Flanders, Habsburg, Tyrol, Pfiert, Kybourg, Artois, and Burgundy; Count Palatine of Haynault, Holland, Zeland, Namur, and Zutphen; Marquess of the Roman Empire and of Burgau, Landgrave of Alsatia, Lord of Frisia, the Wendish Mark, Portenau, Salins, and Malines, etc. etc.[296] Chivalric ordersMaximilian's coin with the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece On 30 April 1478, Maximilian was knighted by Adolph of Cleves, a senior member of the Order of the Golden Fleece and on the same day he became the sovereign of this exalted order. As its head, he did everything in his power to restore its glory as well as associate the order with the Habsburg lineage. He expelled the members who had defected to France and rewarded those loyal to him, and also invited foreign rulers to join its ranks.[297] Maximilian I was a member of the Order of the Garter, nominated by King Henry VII of England in 1489. His Garter stall plate survives in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[298] Maximilian was patron of the Order of Saint George founded by his father, and also the founder of its secular confraternity.[299] Appearance and personality Maximilian was strongly built, had an upright posture, was over six feet tall, had blue eyes, neck length blond or reddish hair, a large hooked nose and a jutting jaw (like his father, he always shaved his beard.[300][301] Although not conventionally handsome, he was well-proportioned and considered physically attractive, with abiding youthfulness and an affable, pleasing manner.[302][303] A womanizer since his teenager days, he increasingly sought distraction from the tragedy of the first marriage and the frustration of the second marriage in the company of "sleeping women" in all corners of his empire. Sigrid-Maria Grössing describes him as a charming heartbreaker for all his life.[304][305] He could manoeuvre with one hand a seven-meter lance comfortably.[306][307] Maximilian was a late developer. According to his teacher Johannes Cuspinian, he did not speak until he was nine-years-old, and after that only developed slowly. Frederick III recalled that when his son was twelve, he still thought that the boy was either mute or stupid.[308] In his adulthood, he spoke six languages (he learned French from his wife Mary)[309] and was a genuinely talented author.[156] Other than languages, mathematics and religion, he painted and played various instruments and was also trained in farming, carpentry and blacksmithing, although the focus of his education was naturally kingship.[310] According to Fichtner, he did not learn much from formal training though, because even as a boy, he never sat still and tutors could not do much about that.[311] Gerhard Benecke opines that by nature he was the man of action, a "vigorously charming extrovert" who had a "conventionally superficial interest in knowledge, science and art combined with excellent health in his youth" (he remained virile into his late thirties and although later his health was damaged due to a leg accident and other ailments, the emperor displayed remarkable self-discipline and hardly ever recognized a weakness; at the 1510 Reichstag in Augsburg, Maximilian, 51, fought against Frederick of Saxony, 47, in front of a large audience.).[312][313] He was brave to the point of recklessness, and this did not only show in battles. He once entered a lion's enclosure in Munich alone to tease the lion, and at another point climbed to the top of the Cathedral of Ulm, stood on one foot and turned himself round to gain a full view, at the trepidation of his attendants. In the nineteenth century, an Austrian officer lost his life trying to repeat the emperor's "feat", while another succeeded.[314][315] While he paid magnificently for a princely style, he required little for personal needs.[316] In his mature years, he exerted restraint on personal habits, except during his depressive phases (when he drank night and day, sometimes incapacitating the government, to the great annoyance of Chancellor Zyprian von Sernteiner) or in the companion of his artist friends. The artists got preferential treatment in criminal matters too, such as the case of Veit Stoss, whose sentence (imprisonment and having his hands chopped off for an actual crime) issued by Nuremberg got cancelled on the sole basis of genius. The emperor's reasoning was that, what came as a gift from God should not be treated according to usual norms or human proportions.[317] To the astonishment of contemporaries, he laughed at the satire directed against his person and organized celebrations after defeats.[318][319] Historian Ernst Bock, with whom Benecke shares the same sentiment, writes the following about him:[320]

Historian Paula Fichtner describes Maximilian as a leader who was ambitious and imaginative to a fault, with self-publicizing tendencies as well as territorial and administrative ambitions that betrayed a nature both "soaring and recognizably modern", while dismissing Benecke's presentation of Maximilian as "an insensitive agent of exploitation" as influenced by the author's personal political leaning.[322] Berenger and Simpson consider Maximilian a greedy Renaissance prince, and also, "a prodigious man of action whose chief fault was to have 'too many irons in the fire'".[323] On the other hand, Steven Beller criticizes him for being too much of a medieval knight who had a hectic schedule of warring, always crisscrossing the whole continent to do battles (for example, in August 1513, he commanded Henry VIII's English army in the second Guinegate, and a few weeks later joined the Spanish forces in defeating the Venetians) with little resources to support his ambitions. According to Beller, Maximilian should have spent more time at home persuading the estates to adopt a more efficient governmental and fiscal system.[324] Thomas A. Brady Jr. praises the emperor's sense of honour, but criticizes his financial immorality—according to Geoffrey Parker, both points, together with Maximilian's martial qualities and hard-working nature, would be inherited from the grandfather by Charles V:[209][325]

Certain English sources describe him as a ruler who habitually failed to keep his words.[326] According to Wiesflecker, people could often depend on his promises more than those of most princes of his days, although he was no stranger to the "clausola francese" and also tended to use a wide variety of statements to cover his true intentions, which unjustly earned him the reputation of being fickle.[327] Hollegger concurs that Maximilian's court officials, except Eitelfriedrich von Zollern and Wolfgang von Fürstenberg, did expect gifts and money for tips and help, and the emperor usually defended his counselors and servants even if he acted against the more blatant displays of material greed. Maximilian though was not a man who could be controlled or influenced easily by his officials. Hollegger also opines that while many of his political and artistic schemes leaned towards megalomania, there was a sober realist who believed in progression and relied on modern modes of management underneath. Personally, "frequently described as humane, gentle, and friendly, he reacted with anger, violence, and vengefulness when he felt his rights had been injured or his honor threatened, both of which he valued greatly." The price for his warlike ruling style and his ambition for a globalized monarchy (that ultimately achieved considerable successes) was a continuous succession of war, that earned him the sobriquet "Heart of steel" (Coeur d'acier).[16][191] Marriages and offspring Maximilian was married three times, but only the first marriage produced offspring:

The marriage produced three children, of whom only two survived:

The drive behind this marriage, to the great annoyance of Frederick III (who characterized it as "disgraceful"), was the desire of personal revenge against the French (Maximilian blamed France for the great tragedies of his life: Mary of Burgundy's death, political upheavals that followed, his troubled relationship with his son, and later, Philip's death[334][335]). The young King of the Romans had in mind a pincer grip against France, while Frederick wanted him to focus on expansion towards the east and maintenance of stability in newly reacquired Austria.[6][7] But Brittany was so weak that by itself it could not resist French attack even briefly as the Burgundian State had done, while Maximilian could not even personally come to Brittany to consummate the marriage.[48]

In addition, he had several illegitimate children, but the number and identities of those are a matter of great debate. Johann Jakob Fugger writes in Ehrenspiegel (Mirror of Honour) that the emperor began fathering illegitimate children after becoming a widower, and that there were eight children in total, four boys and four girls.[341] These were:

Triumphal woodcutsA set of woodcuts called the Triumph of Emperor Maximilian I. In arts and popular cultureMale-line family treeWorks

See also

Notes

References

Sources

Hodnet, Andrew Arthur (2018). The Othering of the Landsknechte. North Carolina State University.

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||