|

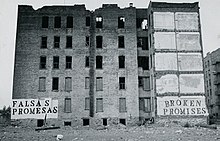

Municipal disinvestmentMunicipal disinvestment is a term in the United States which describes an urban planning process in which a city or town or other municipal entity decides to abandon or neglect an area. It can happen when a municipality is in a period of economic prosperity and sees that its poorest and most blighted communities are both the cheapest targets for revitalization as well as the areas with the greatest potential for improvement.[1] It is when a city is facing urban decay and chooses to allocate fewer resources to the poorest communities or communities with less political power,[2] and disenfranchised neighborhoods are slated for demolition, relocation, and eventual replacement. Disinvestment in urban and suburban communities tends to fall strongly along racial and class lines and may perpetuate the cycle of poverty exerted upon the space, since more affluent individuals with social mobility can more easily leave disenfranchised areas.[3] HistoryNew Deal and postwar eraOut of the New Deal came the Public Works Administration, funding the construction of thousands of low-rent homes and infrastructure development. Meanwhile the Homeowners Refinancing Act, as well as the Wagner-Steagall Housing Act three years later, provided generous incentives and reimbursements aimed at Americans recovering from the Great Depression who could not yet afford to invest in equity. In the postwar era, returning veterans were seeking homes to start families.[4] There was a period of intense residential expansion surrounding major US cities, and banks were gratuitously providing loans in order for families to afford moving there. It is in this new economic landscape where redlining, exclusionary zoning, and predatory lending flourished. The programs that were then enacted provided more displacement than replacement,a nd the beginning years of housing and infrastructure development were defined by their clearance and destruction of communities.[1] The Housing Act of 1949 increased the mandate for public housing, but in claiming to combat "slums" and "blight," it was worded so vaguely that those terms could have been applied to almost all post-Depression urban neighborhoods. What was intended to rebuild in decayed communities was used against poor but otherwise-flourishing neighborhoods by labeling them ghettos.[1] The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 extended demolition of neighborhoods with new roads cutting through the most vulnerable ones to create more direct arteries between the metropolitan and the downtown areas. Highway construction expanded upon the already--widening schism of urban poor and the suburban by further enabling white flight and reducing the focus on public transport. Civil Rights Movement and Great SocietyDuring the postwar era, municipalities sought to grow enriched and modernized communities from the slums that they demolished. As the Civil Rights Movement was in full display through highway revolts and responses to racial violence, there was a growing mindset among urban planners that a communal-focused, people-first approach should be taken, along the same lines as community development handled by the recently-enacted Peace Corps.[5] President Lyndon B. Johnson continued the policies of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy, by signing into law during his first year in office the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and soon a series of bills that comprised the foundation of what was termed the "War on Poverty" and "Great Society" despite the protests from Congress, which was largely against racial integration.[1] The new philosophy of the administration focused intently on Community Action Agencies, fulfilled the demand from modernist social theorists and poured funding and resources into volunteer forces.[5] The direction of policy was seen as some as a form of direct investment in impoverished and minority neighborhoods, in contrast to the previous focus on new construction. Daniel Patrick Moynihan served as Assistant Secretary of Labor under the Johnson administration and was a primary influence on policy development. Stemming from his controversial Moynihan Report, many of the programs that were enacted within the War on Poverty were intended to educate black and poor families to modernize their "culture." Government assistance, in the hundreds of millions of dollars, was intended for organic community growth, the nurturing of local governance, and a gradual transition from developing to developed urban regions. However, when municipalities shrank programs that they directly ran, the money was diverted to smaller unorthodox community action associations with unions or "social protest agendas." For example, in a community center funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Black Panther Party started its development.[5] Change in urban development policyJohnson responded to the radicalization of Watts riots by ceding control of local Offices of Economic Opportunity to municipal authorities such as the mayor, a reversal of the original strategy of community-lead development; funding was reduced; and the practices of the offices and local community projects were more closely supervised.[5] Moynihan was startled by what he perceived as the consequences of the War on Poverty and changed his philosophy and its practice under Johnson. Moynihan found the social policies of the past decades naive in trying to fix the "tangled pathology," which he described in the white paper that he authored for the US Department of Labor, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, nicknamed the Moynihan Report.[1][5][6] Under the Richard Nixon administration, Moynihan remained as Counselor to the President, where he further pushed for dismantling the Offices of Economic Opportunity.[5] It is during that time that Moynihan suggested to Nixon that black communities be treated with a "benign neglect," a philosophy of action that would later be translated into the planned shrinkage policies of the 1970s and 1980s. In 1981, during the Ronald Reagan administration, the OEO changed into the Office of Community Services and became put under the control of Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, who more tightly controlled its function.[5] RedliningExclusionary zoningBenign neglectBenign neglect is a policy proposed in 1969 by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was then on President Richard Nixon's staff as an urban affairs adviser. While serving in this capacity, he sent Nixon a memo that suggested, "The time may have come when the issue of race could benefit from a period of 'benign neglect.' The subject has been too much talked about. The forum has been too much taken over to hysterics, paranoids, and boodlers on all sides. We need a period in which Negro progress continues and racial rhetoric fades."[7] The policy was designed to ease tensions after the Civil Rights Movement of the late 1960s. Moynihan was particularly troubled by the speeches of Vice-President Spiro Agnew. However, the policy was widely seen as the municipal disinvestment to abandon urban neighborhoods, particularly ones with a majority-black population, as Moynihan's statements and writings appeared to encourage, for instance, fire departments engaging in triage to avoid a supposedly-futile war against arson.[2] Planned shrinkage Planned shrinkage is a controversial public policy of the deliberate withdrawal of city services to blighted neighborhoods as a means of coping with dwindling tax revenues.[8] Planned shrinkage involves decreasing city services such as police patrols, garbage removal, street repairs, and fire protection from selected city neighborhoods. It has been advocated as a way to concentrate city services for maximum effectiveness given serious budgetary constraints, but it has been criticized as an attempt to "encourage the exodus of undesirable populations"[8] and to open up blighted neighborhoods for development by private interests. Planned shrinkage occurred in the South Bronx of New York City and in the city of New Orleans.[9][10] The term was first used in New York City in 1976 by Housing Commissioner Roger Starr.[11][12] For example, in the South Bronx, many firehouses were closed from the 1960s to the 1980s. Although firehouses were shut down all over the city during this period, the average number of people per engine by was over 44,000 in the South Bronx compared to just 17,000 in Staten Island. Firehouses in the Bronx were closed even as the fire alarm rate rose during the 1960s and the 1970s. Many of those planning decisions can be tracked to models created by the Rand corporation.[2]: 7 BackgroundDuring the 20th century, a boom in suburban growth caused in part by increased automobile use led to urban decline, particularly in the poorer sections of many large cities in the United States and elsewhere. A dwindling tax base depleted many municipal resources. A common view was that it was part of a "downward spiral" caused first by an absence of jobs, the creation of a permanent underclass, and a declining tax base hurting many city services, including schools. It was that interplay of factors that made change difficult.[13] New York City was described as "so broke" by the 1970s, with neighborhoods that had become "so desperate and depleted" that municipal authorities wondered how to cope.[14] Some authorities felt the process of decline was inevitable and, instead of trying to fight it, searched for alternatives. According to one view, authorities searched for ways to have the greatest population loss in the areas with the poorest non-white populations.[2][12] RAND studyIn the early 1970s, a RAND study examining the relation between city services and large city populations concluded that when services such as police and fire protection were withdrawn, the numbers of people in the neglected areas would decrease.[2] There had been questions about many fires that had been happening in the South Bronx during the 1970s. One account, including the RAND report, suggested that neighborhood fires were predominantly caused by arson though a contrasting report suggested that arson was not a major cause.[15] If arson was a primary cause, according to the RAND viewpoint, it did not make sense financially for the city to try to invest further funds to improve fire protection The RAND report allegedly influenced then US Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who used the report's findings to make recommendations for urban policy. In Moynihan's view, arson was one of many social pathologies caused by large cities, and he suggested that a policy of "benign neglect" would be appropriate as a response.[2] Case studiesNew York City Partly in response to the RAND report, and in an effort to address New York's declining population, New York's housing commissioner, Roger Starr, proposed a policy which he termed planned shrinkage to reduce the impoverished population and better preserve the tax base. According to the "politically toxic" proposal, the city would stop investing in troubled neighborhoods and divert funds to communities "that could still be saved."[16] He suggested that the city should "accelerate the drainage" in what he called the worst parts of the South Bronx through a policy of planned shrinkage by closing subway stations, firehouses, and schools. Starr felt that those actions were the best way to save money.[17] Starr's arguments soon became predominant in urban planning thinking nationwide.[12] The people who lived in the communities where his policies were applied protested vigorously; without adequate fire service and police protection, the residents faced waves of crime and fires that left much of the South Bronx and Harlem devastated.[2] A report in 2011 in the New York Times suggested that the planned shrinkage approach was "short-lived."[18] Under the planned shrinkage program, for example, an abandoned 100-unit development on one piece of land could be cleared by a real estate developer. Such an outcome would be preferable to ten separate neighborhood-based efforts to produce 100 housing units each, according to advocates of planned shrinkage. According to their view, a planned shrinkage approach would encourage so-called "monolithic development," resulting in new urban growth but at much lower population densities than the neighborhoods which had existed previously.[12] The remark by Starr caused a political firestorm, and Mayor Abraham Beame disavowed the idea while City Council members called it "inhuman," "racist," and "genocidal."[11] According to one report, the high inflation during the 1970s combined with the restrictive rent control policies in the city meant that buildings were worth more dead for the insurance money than alive as sources of rental income. As investments, they had limited ability to provide a solid stream of rental income. Accordingly, there was an economic incentive on the part of building owners, according to this view, to simply let the buildings burn. An alternative view was that the fires were a result of the city's municipal policies. While there are differing views about whether planned shrinkage caused fire outbreaks in the 1970s or was a result of such fires, there is agreement that the fires in the South Bronx during those years were extensive.[2]

By the mid-1970s, the Bronx had 120,000 fires per year, or an average of 30 fires every 2 hours. 40 percent of the housing in the area was destroyed. The response time for fires also increased, as the firefighters did not have the resources to keep responding promptly to numerous service calls. A report in The New York Post suggested that the cause of the fires was not arson but resulted from decisions by bureaucrats to abandon sections of the city. According to one report, of the 289 census tracts within the borough of the Bronx, seven census tracts lost more than 97% of their buildings, with 44 tracts losing more than 50% of their buildings, to fire and abandonment.[15] There have been claims that planned shrinkage impacted public health negatively.[19][20] According to one source, public shrinkage programs targeted to undermine populations of African-Americans and Hispanic-Americans in the South Bronx and Harlem had an effect on the geographic pattern of the AIDS outbreak. According to this view, municipal abandonment was interrelated with health issues and helped to cause a phenomenon termed "urban desertification".[21] The populations in the South Bronx, Lower East Side, and Harlem plummeted during the two decades after 1970. Only then would the city again begin to invest in these areas.[citation needed] New OrleansNew Orleans differed from other cities in that the cause of decline was based not on economic or political shifts but by rather a destructive flood caused by a hurricane. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, planned shrinkage was proposed as a means to create a "more compact, more efficient and less flood-prone city".[10] Areas of the city that were most damaged by the flooding and thus were the most likely to be flooded again would not be rebuilt but become green space.[10] Those areas were frequently less desirable, lower-income areas which had lower property values precisely because of the risk of flooding.[10] Some residents rejected a "top-down" approach of planned shrinkage of municipal planners and attempted to rebuild in flood-prone areas.[9] DetroitThe city of Detroit has gone through a major economic and demographic decline in recent decades. The population of the city has fallen from a high of 1,850,000 in 1950 to 677,116 in 2015, kicking it off the top 20 of US cities by population for the first time since 1850.[22] However, the city has a combined statistical area of 5,318,744 people, which currently ranks 12th in the United States. Local crime rates are among the highest in the United States (however, the overall crime rate in the city has seen a decline during the 21st century[23]), and vast areas of the city are in a state of severe urban decay. In 2013, Detroit filed the largest municipal bankruptcy case in US history, which it successfully exited on December 10, 2014. Poverty, crime, shootings, drugs and urban blight in Detroit continue to be ongoing problems. As of 2017[update] median household income is rising,[24] criminal activity is decreasing by 5% annually as of 2017,[25] and the city's blight removal project is making progress in ridding the city of all abandoned homes that cannot be rehabilitated. Roxbury, BostonPlanned shrinkage in Roxbury, Boston is not unique to the RAND policies enacted in the 1970s and 1980s. The neighborhood succumbed to numerous fires by out-of-town landlords seeking out the only way to earn back some profit on homes that no longer sold. However, the neighborhood's response to planned shrinkage through community action has made it an example to other neighborhoods of the success of people-first organizing. The neighborhood had worked with the Boston's administration but refused to give in to bureaucratic control by the city and protested whenever the city neglected its redevelopment.[26] "Shrink to survive""Shrink to survive" is a contemporary form of planned shrinkage which emphasizes short-term razing of the city. If a city enacting planned shrinkage policies takes a laissez-faire approach to disinvesting in its communities, cities can take an active role in that reduction. That includes investing in more aggressive land buyback and enforcement of eminent domain in order to obtain ownership of a property, relocate its residents, and demolish it.[27]  Such proposals, which began around 2009, entail razing entire districts within some cities or else bulldozing them to return the land to its pre-construction rural state.[28] The policies have been studied not only by municipal and state authorities but also by the federal government, and may affect dozens of declining cities in the United States.[29] One report suggested that 50 US cities were potential candidates; they include Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Baltimore and Memphis.[28] Proponents claim the plan will bring efficiency with less waste and fraud;[28] detractors complain the policy has been a "disaster" and advocate for community-based efforts instead.[30] FlintShrink to survive was initiated by Dan Kildee during his term as Treasurer of Genesee County, Michigan.[31] He proposed it as a way to handle municipal problems in Flint, which had experienced an exodus of people and business during the automobile industry downturn.[32] Flint had been described as one of the poorest Rust Belt cities.[28] One estimate was that its population had declined by half since 1950.[32][33] In 2002, authorities established a "municipal land bank" to buy abandoned or foreclosed homes to prevent them from being bought up by real estate speculators.[31] One report was that by the summer of 2009, 1,100 homes in Flint had been bulldozed and that another 3,000 had been scheduled for demolition. One estimate was that the city's size would shrink by twenty per cent,[31][34] while a second estimate was that it needed to contract by 40% to once again become viable financially. In other citiesShrink to survive has been enacted in other medium-sized cities in the American Rust belt such as the Michigan city Benton Harbor,[13] as well as the Ohio city of Youngstown.[35] One report suggested that city authorities in Youngstown had demolished 2,000 derelict homes and businesses.[35] In addition, shrink-to-survive has been considered for inner city suburbs of Detroit.[32] Municipal authorities in Gary, Indiana, are considering plans to shrink the city by 40%, possibly by demolition or by letting nature overgrow abandoned buildings, as a way to raise values for existing structures, reduce crime, and restore the city to fiscal health.[36] The city has suffered a sustained decline in job losses, followed by a housing bust.[36]

See also

References

Further reading

External linksLook up benign neglect in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

|