|

Ninja

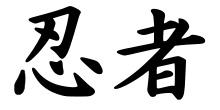

A ninja (Japanese: 忍者; [ɲiꜜɲdʑa]) or shinobi (Japanese: 忍び; [ɕinobi]) was a covert agent, mercenary, or guerrilla warfare expert in feudal Japan. The functions of a ninja included siege and infiltration, ambush, reconnaissance, espionage, deception, and later bodyguarding and their fighting skills in martial arts, including ninjutsu.[1] Their covert methods of waging irregular warfare were deemed dishonorable and beneath the honor of the samurai.[2] Though shinobi proper, as specially trained warriors, spies, and mercenaries, appeared in the 15th century during the Sengoku period,[3] antecedents may have existed as early as the 12th century.[4][5] In the unrest of the Sengoku period, jizamurai families, that is, elite peasant-warriors, in Iga Province and the adjacent Kōka District formed ikki – "revolts" or "leagues" – as a means of self-defense. They became known for their military activities in the nearby regions and sold their services as mercenaries and spies. It is from these areas that much of the knowledge regarding the ninja is drawn.[6] Following the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th century, the ninja faded into obscurity.[7] A number of shinobi manuals, often based on Chinese military philosophy, were written in the 17th and 18th centuries, most notably the Bansenshūkai (1676).[8] By the time of the Meiji Restoration (1868), shinobi had become a topic of popular imagination and mystery in Japan. Ninja figured prominently in legend and folklore, where they were associated with legendary abilities such as invisibility, walking on water, and control over natural elements. Much of their perception in popular culture is based on such legends and folklore, as opposed to the covert actors of the Sengoku period. Etymology Ninja is the on'yomi (Early Middle Chinese–influenced) reading of the two kanji "忍者". In the native kun'yomi reading, it is pronounced shinobi, a shortened form of shinobi-no-mono (忍びの者).[9] The word shinobi appears in the written record as far back as the late 8th century in poems in the Man'yōshū.[10][11] The underlying connotation of shinobi (忍) means "to steal away; to hide" and—by extension—"to forbear", hence its association with stealth and invisibility. Mono (者) means "a person". Historically, the word ninja was not in common use, and a variety of regional colloquialisms evolved to describe what would later be dubbed ninja. Along with shinobi, these include monomi ("one who sees"), nokizaru ("macaque on the roof"), rappa ("ruffian"), kusa ("grass") and Iga-mono ("one from Iga").[7] In historical documents, shinobi is almost always used. Kunoichi (くノ一) is, originally, an argot which means "woman";[12]: p168 it supposedly comes from the characters くノ一 (respectively hiragana ku, katakana no and kanji ichi), which make up the three strokes that form the kanji for "woman" (女).[12]: p168 In fiction written in the modern era kunoichi means "female ninja".[12]: p167 In the Western world, the word ninja became more prevalent than shinobi in the post–World War II culture, possibly because it was more comfortable for Western speakers.[13] In English, the plural of ninja can be either unchanged as ninja, reflecting the Japanese language's lack of grammatical number, or the regular English plural ninjas.[14] HistoryIn Sakura doki onna gyoretsu, this onnagata is attended by three kuroko. In Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji, Ashikaga Mitsuuji is approached unknowingly by a ninja. Despite many popular folktales, historical accounts of the ninja are scarce. Historian Stephen Turnbull asserts that the ninja were mostly recruited from the lower class, and therefore little literary interest was taken in them.[16] The social origin of the ninja is seen as the reason they agree to operate in secret, trading their service for money without honor and glory.[17] The scarcity of historical accounts is also demonstrated in war epics such as The Tale of Hōgen (Hōgen Monogatari) and The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari), which focus mainly on the aristocratic samurai, whose deeds were apparently more appealing to the audience.[13] Historian Kiyoshi Watatani states that the ninja were trained to be particularly secretive about their actions and existence:

However, some ninjutsu books described specifically what tactics ninja should use to fight, and the scenarios in which a ninja might find themselves can be deduced from those tactics. For example, in the manuscript of volume 2 of Kanrin Seiyō (間林清陽) which is the original book of Bansenshūkai (万川集海), there are 48 points of ninja's fighting techniques, such as how to make makibishi from bamboo, how to make footwear that makes no sound, fighting techniques when surrounded by many enemies, precautions when using swords at night, how to listen to small sounds, kuji-kiri that prevents guard dogs from barking, and so on.[19][20] Predecessors The title ninja has sometimes been attributed retrospectively to the semi-legendary 2nd-century prince Yamato Takeru.[21] In the Kojiki, the young Yamato Takeru disguised himself as a charming maiden and assassinated two chiefs of the Kumaso people.[22] However, these records take place at a very early stage of Japanese history, and they are unlikely to be connected to the shinobi of later accounts. The first recorded use of espionage was under the employment of Prince Shōtoku in the 6th century.[23] Such tactics were considered unsavory even in early times, when, according to the 10th-century Shōmonki, the boy spy Hasetsukabe no Koharumaru was killed for spying against the insurgent Taira no Masakado.[24] Later, the 14th-century war chronicle Taiheiki contained many references to shinobi[21] and credited the destruction of a castle by fire to an unnamed but "highly skilled shinobi".[25] Early historyIt was not until the 15th century that spies were specially trained for their purpose.[16] It was around this time that the word shinobi appeared to define and clearly identify ninja as a secretive group of agents. Evidence for this can be seen in historical documents, which began to refer to stealthy soldiers as shinobi during the Sengoku period.[26] Later manuals regarding espionage are often grounded in Chinese military strategy, quoting works such as The Art of War by Sun Tzu.[27] The ninja emerged as mercenaries in the 15th century, where they were recruited as spies, raiders, arsonists and even terrorists. Amongst the samurai, a sense of ritual and decorum was observed, where one was expected to fight or duel openly. Combined with the unrest of the Sengoku period, these factors created a demand for men willing to commit deeds considered disreputable for conventional warriors.[23][2] By the Sengoku period, the shinobi had several roles, including spy (kanchō), scout (teisatsu), surprise attacker (kishu), and agitator (konran).[26] The ninja families were organized into larger guilds, each with their own territories.[28] A system of rank existed. A jōnin ("upper person") was the highest rank, representing the group and hiring out mercenaries. This is followed by the chūnin ("middle person"), assistants to the jōnin. At the bottom was the genin ("lower person"), field agents drawn from the lower class and assigned to carry out actual missions.[29] Iga and Kōga clans The Iga and Kōga "clans" were jizamurai families living in the province of Iga (modern Mie Prefecture) and the adjacent region of Kōka (later written as Kōga), named after a village in what is now Shiga Prefecture. From these regions, villages devoted to the training of ninja first appeared.[30] The remoteness and inaccessibility of the surrounding mountains in Iga may have had a role in the ninja's secretive development.[29] Historical documents regarding the ninja's origins in these mountainous regions are considered generally correct.[31] The chronicle Go Kagami Furoku writes, of the two clans' origins:

Likewise, a supplement to the Nochi Kagami, a record of the Ashikaga shogunate, confirms the same Iga origin:

A distinction is to be made between the ninja from these areas, and commoners or samurai hired as spies or mercenaries. Unlike their counterparts, the Iga and Kōga clans were professionals, specifically trained for their roles.[26] These professional ninja were actively hired by daimyōs between 1485 and 1581.[26] Specifically, the Iga professionals were sought after for their skill at siege warfare, or "shirotori", which included night attacks and ambush.[33] By the 1460s, the leading families in the regions had established de facto independence from their shugo. The Kōka ikki persisted until 1574, when it was forced to become a vassal of Oda Nobunaga. The Iga ikki continued until 1581, when Nobunaga invaded Iga Province and wiped out the organized clans.[34] Survivors were forced to flee, some to the mountains of Kii, but others arrived before Tokugawa Ieyasu, where they were well treated.[35] Some former Iga clan members, including Hattori Hanzō, would later serve as Tokugawa's bodyguards.[36] Prior to the conquest of Kōka in 1574, the two confederacies worked in alliance together from at least 1487. Following the Battle of Okehazama in 1560, Tokugawa employed a group of eighty Kōga ninja, led by Tomo Sukesada. They were tasked to raid an outpost of the Imagawa clan. The account of this assault is given in the Mikawa Go Fudoki, where it was written that Kōga ninja infiltrated the castle, set fire to its towers, and killed the castellan along with two hundred of the garrison.[37] Activities under TokugawaAfter the assassination of Oda Nobunaga, Iga and Kōka ninja, according to tradition, helped Ieyasu undergo an arduous journey to escape the enemies of Nobunaga in Sakai and return to Mikawa. However, their journey was very dangerous due to the existence of "Ochimusha-gari" groups across the route.[a] During this journey, Tokugawa generals such as Ii Naomasa, Sakai Tadatsugu and Honda Tadakatsu fought their way through raids and harassment from Ochimusha-gari (Samurai hunter) outlaws to secure the way for Ieyasu, while sometimes advancing by usage of gold and silver bribes given to some of the more amenable Ochimusha-gari groups.[41] As they reached Kada, an area between Kameyama town and Iga,[42] The attacks from Ochimusha-gari finally ended as they reached the former territory of the Kōka ikki, who were friendly to the Tokugawa clan. The Koka ninja assisted the Tokugawa escort group in eliminating the threats of Ochimusha-gari outlaws then escorting them until they reached Iga Province, where they were further protected by samurai clans from Iga ikki which accompanied the Ieyasu group until they safely reached Mikawa. The Ietada nikki journal records that the escort group of Ieyasu has killed some 200 outlaws during their journey from Osaka.[43][44] The Kōga ninja are said to have played a role in the later Battle of Sekigahara (1600), where several hundred Kōga assisted soldiers under Torii Mototada in the defence of Fushimi Castle.[45] After Tokugawa's victory at Sekigahara, the Iga acted as guards for the inner compounds of Edo Castle, while the Kōga acted as a police force and assisted in guarding the outer gate.[36] In 1603, a group of ninja warriors from Iga clan led by Miura Yo'emon were assigned under the command of Red Demon brigades of Ii Naomasa, the daimyo of Hikone under Tokugawa shogunate.[46][47] In 1608, a daimyo named Tōdō Takatora was assigned by Ieyasu to control of Tsu, a newly established domain which covered portions of Iga and Ise Province. The domain at first worth of to the 220,000,[48] then grow further in productivity to the total revenue of 320,000 koku under Takatora governance.[49][50] It was reported that Tōdō Takatora employs the Iga-ryū Ninjas.[51][46] Aside from Ninjas, he also employs local clans of Iga province as "Musokunin", which is a class of part time Samurai who has been allowed to retain their clan name but does not own any land or Han. The Musokunin also worked as farmer during peace, while they are obliged to take arms in the time of war.[52][51][53] In 1614, The Iga province warriors saw action during the siege of Osaka. Takatora brought the Musokunin auxiliaries from Iga province to besiege the Osaka castle during the winter phase.[52][51] Meanwhile the ninja units of Iga province were deployed under several commanders such as Hattori Hanzō, and Yamaoka Kagetsuge, and Ii Naotora, heir of Naomasa who also given control of Ii clan's Red Demons ninjas after Naomasa died.[46][47] Later in 1615, during the summer phase of Osaka siege, The Ii clan Red Demons ninjas led by Miura Yo'emon, Shimotani Sanzo, Okuda Kasa'emon, and Saga Kita'emon saw action once again during the Battle of Tennōji, as they were reportedly fought together with the Tokugawa regular army storming on the south gate of Osaka castle.[47] In 1614, the initial "winter campaign" at the Siege of Osaka saw the ninja in use once again. Miura Yoemon, a ninja in Tokugawa's service, recruited shinobi from the Iga region, and sent 10 ninja into Osaka Castle in an effort to foster antagonism between enemy commanders.[54] During the later "summer campaign", these hired ninja fought alongside regular troops at the Battle of Tennōji.[54] Shimabara rebellion A final but detailed record of ninja employed in open warfare occurred during the Shimabara Rebellion (1637–1638).[55] The Kōga ninja were recruited by shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu against Christian rebels led by Amakusa Shirō, who made a final stand at Hara Castle, in Hizen Province. A diary kept by a member of the Matsudaira clan, the Amakusa Gunki, relates: "Men from Kōga in Ōmi Province who concealed their appearance would steal up to the castle every night and go inside as they pleased."[56] The Ukai diary, written by a descendant of Ukai Kanemon, has several entries describing the reconnaissance actions taken by the Kōga.

Suspecting that the castle's supplies might be running low, the siege commander Matsudaira Nobutsuna ordered a raid on the castle's provisions. Here, the Kōga captured bags of enemy provisions, and infiltrated the castle by night, obtaining secret passwords.[57] Days later, Nobutsuna ordered an intelligence gathering mission to determine the castle's supplies. Several Kōga ninja—some apparently descended from those involved in the 1562 assault on an Imagawa clan castle—volunteered despite being warned that chances of survival were slim.[58] A volley of shots was fired into the sky, causing the defenders to extinguish the castle lights in preparation. Under the cloak of darkness, ninja disguised as defenders infiltrated the castle, capturing a banner of the Christian cross.[58] The Ukai diary writes,

As the siege went on, the extreme shortage of food later reduced the defenders to eating moss and grass.[59] This desperation would mount to futile charges by the rebels, where they were eventually defeated by the shogunate army. The Kōga would later take part in conquering the castle:

With the fall of Hara Castle, the Shimabara Rebellion came to an end, and Christianity in Japan was forced underground.[61] These written accounts are the last mention of ninja in war.[62] Edo periodAfter the Shimabara Rebellion, there were almost no major wars or battles until the bakumatsu era. To earn a living, ninja had to be employed by the governments of their Han (domain), or change their profession. Many lords still hired ninja, not for battle but as bodyguards or spies. Their duties included spying on other domains, guarding the daimyō, and fire patrol.[63] A few domains like Tsu, Hirosaki and Saga continued to employ their own ninja into the bakumatsu era, although their precise numbers are unknown.[64][65] Many former ninja were employed as security guards by the Tokugawa shogunate, though the role of espionage was transferred to newly created organizations like the onmitsu and the oniwaban.[66] Others used their ninjutsu knowledge to become doctors, medicine sellers, merchants, martial artists, and fireworks manufacturers.[67] Some unemployed ninja were reduced to banditry, such as Fūma Kotarō and Ishikawa Goemon.[68]

OniwabanIn the early 18th century, shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune founded the oniwaban ("garden keepers"), an intelligence agency and secret service. Members of the oniwaban were agents involved in collecting information on daimyō and government officials.[70] The secretive nature of the oniwaban—along with the earlier tradition of using Iga and Kōga clan members as palace guards—have led some sources to define the oniwabanshū as "ninja".[71] This portrayal is also common in later novels and jidaigeki. However, there is no written link between the earlier shinobi and the later oniwaban. Ninja stereotypes in theatreMany ubiquitous stereotypes about ninja were developed within Edo theatre. These include their black clothing, which was supposed to imitate the outfits worn by kuroko, stagehands meant to be ignored by the audience; and their use of shuriken, which was meant to contrast with the use of swords by onstage samurai. In kabuki theatre, ninja were "dishonorable and often sorcerous counterparts" to samurai, and possessed "almost, if not outright, magical means of camouflage."[15] Contemporary Between 1960 and 2010 artifacts dating to the Siege of Odawara (1590) were uncovered which experts say are ninja weapons.[72] Ninja were spies and saboteurs and likely participated in the siege.[72] The Hojo clan failed to save the castle from Toyotomi Hideyoshi forces.[72] The uncovered flat throwing stones are likely predecessors of the shuriken.[72] The clay caltrops preceded makibishi caltrops.[72] Archeologist Iwata Akihiro of Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore said the flat throwing stones "were used to stop the movement of the enemy who was going to attack [a soldier] at any moment, and while the enemy freezed the soldier escaped,".[72] The clay caltrops could "stop the movement of the enemy who invaded the castle," These weapons were hastily constructed yet effective and used by a "battle group which can move into action as ninjas".[72] In 2012, Jinichi Kawakami, the last authentic heir of ninjutsu, decided against passing on his teaching to any student, stating that the art of ninjutsu has no place in modern times.[73] Instead, Kawakami serves as the honorary director of the Iga-ryu Ninja Museum and researches ninjutsu as a specially appointed professor at Mie University.[74][75] Mie University founded the world's first research centre devoted to the ninja in 2017. A graduate master course opened in 2018. It is located in Iga (now Mie Prefecture). There are approximately 3 student enrollments per year. Students must pass an admission test about Japanese history and be able to read historical ninja documents.[76] Scientific researchers and scholars of different disciplines study ancient documents and how it can be used in the modern world.[77] In 2020, the 45-year-old Genichi Mitsuhashi was the first student to graduate from the master course of ninja studies at Mie University. For 2 years he studied historical records and the traditions of the martial art. Similar to the original ninja, by day he was a farmer and grew vegetables while he did ninja studies and trained martial arts in the afternoon.[76] On June 19, 2022, Kōka city in Shiga Prefecture announced that a written copy of "Kanrinseiyo", which is the original source of a famous book on the art of ninja called "Bansenshukai" (1676) from the Edo period was discovered in a warehouse of Kazuraki Shrine.[78] The handwritten reproduction was produced in 1748.[79] The book describes 48 types of ninjutsu.[78] It has information about specific methods such as attaching layers of cotton to the bottom of straw sandals to prevent noise when sneaking around, attacking to the right when surrounded by a large number of enemies, throwing charred owl and turtle powder when trying to hide, and casting spells.[78] It also clarified methods and how to manufacture and use ninjutsu tools, such as cane swords and "makibishi" (Japanese caltrop).[78] RolesThe ninja were stealth soldiers and mercenaries hired mostly by daimyōs.[80] Their primary roles were those of espionage and sabotage, although assassinations were also attributed to ninja. Although they were considered the anti-samurai and were disdained by those belonging to the samurai class, they were necessary for warfare and were even employed by the samurai themselves to carry out operations that were forbidden by bushidō.[17]  In his Buke Myōmokushō, military historian Hanawa Hokinoichi writes of the ninja:

EspionageEspionage was the chief role of the ninja. With the aid of disguises, the ninja gathered information on enemy terrain and building specifications, as well as obtaining passwords and communiques. The aforementioned supplement to the Nochi Kagami briefly describes the ninja's role in espionage:

Later in history, the Kōga ninja would become regarded as agents of the Tokugawa bakufu, at a time when the bakufu used the ninja in an intelligence network to monitor regional daimyōs as well as the Imperial court.[28] SabotageArson was the primary form of sabotage practiced by the ninja, who targeted castles and camps. The Tamon-in Nikki (16th century)—a diary written by abbot Eishun of Kōfuku-ji temple—describes an arson attack on a castle by men of the Iga clans.

In 1558, Rokkaku Yoshikata employed a team of ninja to set fire to Sawayama Castle. A chūnin captain led a force of 48 ninja into the castle by means of deception. In a technique dubbed bakemono-jutsu ("ghost technique"), his men stole a lantern bearing the enemy's family crest (mon), and proceeded to make replicas with the same mon. By wielding these lanterns, they were allowed to enter the castle without a fight. Once inside, the ninja set fire to the castle, and Yoshitaka's army would later emerge victorious.[83] The mercenary nature of the shinobi is demonstrated in another arson attack soon after the burning of Sawayama Castle. In 1561, commanders acting under Kizawa Nagamasa hired three Iga ninja of genin rank to assist the conquest of a fortress in Maibara. Rokkaku Yoshitaka, the same man who had hired Iga ninja just years earlier, was the fortress holder—and target of attack. The Asai Sandaiki writes of their plans: "We employed shinobi-no-mono of Iga... They were contracted to set fire to the castle".[84] However, the mercenary shinobi were unwilling to take commands. When the fire attack did not begin as scheduled, the Iga men told the commanders, who were not from the region, that they could not possibly understand the tactics of the shinobi. They then threatened to abandon the operation if they were not allowed to act on their own strategy. The fire was eventually set, allowing Nagamasa's army to capture the fortress in a chaotic rush.[84] Assassination The best-known cases of assassination attempts involve famous historical figures. Deaths of famous persons have sometimes been attributed to assassination by ninja, but the secretive natures of these scenarios have made them difficult to prove.[16] Assassins were often identified as ninja later on, but there is no evidence to prove whether some were specially trained for the task or simply a hired thug. The warlord Oda Nobunaga's notorious reputation led to several attempts on his life. In 1571, a Kōga ninja and sharpshooter by the name of Sugitani Zenjubō was hired to assassinate Nobunaga. Using two arquebuses, he fired two consecutive shots at Nobunaga, but was unable to inflict mortal injury through Nobunaga's armor.[85] Sugitani managed to escape, but was caught four years later and put to death by torture.[85] In 1573, Manabe Rokurō, a vassal of daimyō Hatano Hideharu, attempted to infiltrate Azuchi Castle and assassinate the sleeping Nobunaga. However, this also ended in failure, and Manabe was forced to commit suicide, after which his body was openly displayed in public.[85] According to a document, the Iranki, when Nobunaga was inspecting Iga province—which his army had devastated—a group of three ninja shot at him with large-caliber firearms. The shots flew wide of Nobunaga, however, and instead killed seven of his surrounding companions.[86] The ninja Hachisuka Tenzō was sent by Nobunaga to assassinate the powerful daimyō Takeda Shingen, but ultimately failed in his attempts. Hiding in the shadow of a tree, he avoided being seen under the moonlight, and later concealed himself in a hole he had prepared beforehand, thus escaping capture.[87] An assassination attempt on Toyotomi Hideyoshi was also thwarted. A ninja named Kirigakure Saizō (possibly Kirigakure Shikaemon) thrust a spear through the floorboards to kill Hideyoshi, but was unsuccessful. He was "smoked out" of his hiding place by another ninja working for Hideyoshi, who apparently used a sort of primitive "flamethrower".[88] Unfortunately, the veracity of this account has been clouded by later fictional publications depicting Saizō as one of the legendary Sanada Ten Braves. Uesugi Kenshin, the famous daimyō of Echigo Province, was rumored to have been killed by a ninja. The legend credits his death to an assassin who is said to have hidden in Kenshin's lavatory, and fatally injured Kenshin by thrusting a blade or spear into his anus.[89] While historical records showed that Kenshin suffered abdominal problems, modern historians have generally attributed his death to stomach cancer, esophageal cancer, or cerebrovascular disease.[90] Psychological warfareIn battle, the ninja were also used to cause confusion amongst the enemy.[91] A degree of psychological warfare in the capturing of enemy banners can be seen illustrated in the Ōu Eikei Gunki, composed between the 16th and 17th centuries:

CountermeasuresA variety of countermeasures were taken to prevent the activities of the ninja. Precautions were often taken against assassinations, such as weapons concealed in the lavatory, or under a removable floorboard.[93] Buildings were constructed with traps and trip wires attached to alarm bells.[94] Japanese castles were designed to be difficult to navigate, with winding routes leading to the inner compound. Blind spots and holes in walls provided constant surveillance of these labyrinthine paths, as exemplified in Himeji Castle. Nijō Castle in Kyoto is constructed with long "nightingale" floors, which rested on metal hinges (uguisu-bari) specifically designed to squeak loudly when walked over.[95] Grounds covered with gravel also provided early notice of unwanted intruders, and segregated buildings allowed fires to be better contained.[96] TrainingThe skills required of the ninja have come to be known in modern times as ninjutsu (忍術), but it is unlikely they were previously named under a single discipline, rather distributed among a variety of espionage and survival skills. Some view ninjutsu as evidence that ninja were not simple mercenaries because texts contained not only information on combat training, but also information about daily needs, which even included mining techniques.[97] The guidance provided for daily work also included elements that enable the ninja to understand the martial qualities of even the most menial task.[97] These factors show how the ninjutsu established among the ninja class the fundamental principle of adaptation.[97]  The first specialized training began in the mid-15th century, when certain samurai families started to focus on covert warfare, including espionage and assassination.[98] Like the samurai, ninja were born into the profession, where traditions were kept in, and passed down through the family.[28][99] According to Turnbull, the ninja was trained from childhood, as was also common in samurai families. Outside the expected martial art disciplines, a youth studied survival and scouting techniques, as well as information regarding poisons and explosives.[100] Physical training was also important, which involved long-distance runs, climbing, stealth methods of walking[101] and swimming.[102] A certain degree of knowledge regarding common professions was also required if one was expected to take their form in disguise.[100] Some evidence of medical training can be derived from one account, where an Iga ninja provided first-aid to Ii Naomasa, who was injured by gunfire in the Battle of Sekigahara. Here the ninja reportedly gave Naomasa a "black medicine" meant to stop bleeding.[103] With the fall of the Iga and Kōga clans, daimyōs could no longer recruit professional ninja, and were forced to train their own shinobi. The shinobi was considered a real profession, as demonstrated in the 1649 bakufu law on military service, which declared that only daimyōs with an income of over 10,000 koku were allowed to retain shinobi.[104] In the two centuries that followed, a number of ninjutsu manuals were written by descendants of Hattori Hanzō as well as members of the Fujibayashi clan, an offshoot of the Hattori. Major examples include the Ninpiden (1655), the Bansenshūkai (1675), and the Shōninki (1681).[8] Modern schools that claim to train ninjutsu arose from the 1970s, including that of Masaaki Hatsumi (Bujinkan), Stephen K. Hayes (To-Shin Do), and Jinichi Kawakami (Banke Shinobinoden). The lineage and authenticity of these schools are a matter of controversy.[105] TacticsThe ninja did not always work alone. Teamwork techniques exist: For example, in order to scale a wall, a group of ninja may carry each other on their backs, or provide a human platform to assist an individual in reaching greater heights.[106] The Mikawa Go Fudoki gives an account where a coordinated team of attackers used passwords to communicate. The account also gives a case of deception, where the attackers dressed in the same clothes as the defenders, causing much confusion.[37] When a retreat was needed during the Siege of Osaka, ninja were commanded to fire upon friendly troops from behind, causing the troops to charge backwards to attack a perceived enemy. This tactic was used again later on as a method of crowd dispersal.[54] Most ninjutsu techniques recorded in scrolls and manuals revolve around ways to avoid detection, and methods of escape.[8] These techniques were loosely grouped under corresponding natural elements. Some examples are:

DisguisesThe use of disguises is common and well documented. Disguises came in the form of priests, entertainers, fortune tellers, merchants, rōnin, and monks.[108] The Buke Myōmokushō states,

A mountain ascetic (yamabushi) attire facilitated travel, as they were common and could travel freely between political boundaries. The loose robes of Buddhist priests also allowed concealed weapons, such as the tantō.[109] Minstrel or sarugaku outfits could have allowed the ninja to spy in enemy buildings without rousing suspicion. Disguises as a komusō, a mendicant monk known for playing the shakuhachi, were also effective, as the large "basket" hats traditionally worn by them concealed the head completely.[110] EquipmentNinja used a large variety of tools and weaponry, some of which were commonly known, but others were more specialized. Most were tools used in the infiltration of castles. A wide range of specialized equipment is described and illustrated in the 17th-century Bansenshūkai,[111] including climbing equipment, extending spears,[103] rocket-propelled arrows,[112] and small collapsible boats.[113] Outerwear  While the image of a ninja clad in black garb (shinobi shōzoku) is prevalent in popular media, there is no hard evidence for such attire.[114] It is theorized that, instead, it was much more common for the ninja to be disguised as civilians. The popular notion of black clothing may be rooted in artistic convention; early drawings of ninja showed them dressed in black to portray a sense of invisibility.[81] This convention may have been borrowed from the puppet handlers of bunraku theater, who dressed in total black in an effort to simulate props moving independently of their controls.[115] However, it has been put forward by some authorities that black robes, perhaps slightly tainted with red to hide bloodstains, was indeed the sensible garment of choice for infiltration.[81] Clothing used was similar to that of the samurai, but loose garments (such as leggings) were tucked into trousers or secured with belts. The tenugui, a piece of cloth also used in martial arts, had many functions. It could be used to cover the face, form a belt, or assist in climbing. The historicity of armor specifically made for ninja cannot be ascertained. While pieces of light armor purportedly worn by ninja exist and date to the right time, there is no hard evidence of their use in ninja operations. Depictions of famous persons later deemed ninja often show them in samurai armor. There were lightweight concealable types of armour made with kusari (chain armour) and small armor plates such as karuta that could have been worn by ninja including katabira (jackets) made with armour hidden between layers of cloth. Shin and arm guards, along with metal-reinforced hoods are also speculated to make up the ninja's armor.[81] Tools Tools used for infiltration and espionage are some of the most abundant artifacts related to the ninja. Ropes and grappling hooks were common, and were tied to the belt.[111] A collapsible ladder is illustrated in the Bansenshukai, featuring spikes at both ends to anchor the ladder.[116] Spiked or hooked climbing gear worn on the hands and feet also doubled as weapons.[117] Other implements include chisels, hammers, drills, picks, and so forth. The kunai was a heavy pointed tool, possibly derived from the Japanese masonry trowel, which it closely resembles. Although it is often portrayed in popular culture as a weapon, the kunai was primarily used for gouging holes in walls.[118] Knives and small saws (hamagari) were also used to create holes in buildings, where they served as a foothold or a passage of entry.[119] A portable listening device (saoto hikigane) was used to eavesdrop on conversations and detect sounds.[120] A line reel device known as a Toihikinawa (間引縄 / probing pulling rope) was used in pitch dark for finding the distance and route of entry. The mizugumo was a set of wooden shoes supposedly allowing the ninja to walk on water.[113] They were meant to work by distributing the wearer's weight over the shoes' wide bottom surface. The word mizugumo is derived from the native name for the Japanese water spider (Argyroneta aquatica japonica). The mizugumo was featured on the show MythBusters, where it was demonstrated unfit for walking on water. The ukidari, a similar footwear for walking on water, also existed in the form of a flat round bucket, but was probably quite unstable.[121] Inflatable skins and breathing tubes allowed the ninja to stay underwater for longer periods of time.[122] Goshiki-mai (go, five; shiki, color; mai, rice) colored (red, blue, yellow, black, purple)[123] rice grains were used in a code system,[124][125] and to make trails that could be followed later.[126][127][128] Despite the large array of tools available to the ninja, the Bansenshukai warns one not to be overburdened with equipment, stating "a successful ninja is one who uses but one tool for multiple tasks".[129] WeaponryAlthough shorter swords and daggers were used, the katana was probably the ninja's weapon of choice, and was sometimes carried on the back.[110] The katana had several uses beyond normal combat. In dark places, the scabbard could be extended out of the sword, and used as a long probing device.[130] The sword could also be laid against the wall, where the ninja could use the sword guard (tsuba) to gain a higher foothold.[131] The katana could even be used as a device to stun enemies before attacking them, by putting a combination of red pepper, dirt or dust, and iron filings into the area near the top of the scabbard, so that as the sword was drawn the concoction would fly into the enemy's eyes, stunning him until a lethal blow could be made. While straight swords were used before the invention of the katana,[132] there's no known historical information about the straight ninjatō pre-20th century. The first photograph of a ninjatō appeared in a booklet by Heishichirō Okuse in 1956.[133][full citation needed][134] A replica of a ninjatō is on display at the Ninja Museum of Igaryu.  An array of darts, spikes, knives, and sharp, star-shaped discs were known collectively as shuriken.[135] While not exclusive to the ninja,[136] they were an important part of the arsenal, where they could be thrown in any direction.[137] Bows were used for sharpshooting, and some ninjas' bows were intentionally made smaller than the traditional yumi (longbow).[138] The chain and sickle (kusarigama) was also used by the ninja.[139] This weapon consisted of a weight on one end of a chain, and a sickle (kama) on the other. The weight was swung to injure or disable an opponent, and the sickle used to kill at close range. Explosives introduced from China were known in Japan by the time of the Mongol Invasions in the 13th century.[140] Later, explosives such as hand-held bombs and grenades were adopted by the ninja.[122] Soft-cased bombs were designed to release smoke or poison gas, along with fragmentation explosives packed with iron or ceramic shrapnel.[106] Along with common shinobi buki (ninja weapons), a large assortment of miscellaneous arms were associated with the ninja.[141] Some examples include poison,[111] makibishi (caltrops),[142] shikomizue (cane swords),[143] land mines,[144] fukiya (blowguns), poisoned darts, acid-spurting tubes, and teppo jutsu (firearms).[122][145] The happō, a small eggshell filled with metsubushi (blinding powder), was also used to facilitate escape.[146] Legendary abilitiesSuperhuman or supernatural powers were often associated with the ninja with a style of Japanese martial arts in ninjutsu. Some legends include flight, invisibility, shapeshifting, teleportation, the ability to "split" into multiple bodies (bunshin), the summoning of animals (kuchiyose), and control over the five classical elements. These fabulous notions have stemmed from popular imagination regarding the ninja's mysterious status, as well as romantic ideas found in later Japanese art of the Edo period. Magical powers were rooted in the ninja's own misinformation efforts to disseminate fanciful information. For example, Nakagawa Shoshunjin, the 17th-century founder of Nakagawa-ryū, claimed in his own writings (Okufuji Monogatari) that he had the ability to transform into birds and animals.[104] Perceived control over the elements may be grounded in real tactics, which were categorized by association with forces of nature. For example, the practice of starting fires to cover a ninja's trail falls under katon-no-jutsu ("fire techniques").[142] By dressing in identical clothing, a coordinated team of ninjas could instill the perception of a single assailant being in multiple locations.  The ninja's adaption of kites in espionage and warfare is another subject of legends. Accounts exist of ninja being lifted into the air by kites, where they flew over hostile terrain and descended into, or dropped bombs on enemy territory.[113] Kites were indeed used in Japanese warfare, but mostly for the purpose of sending messages and relaying signals.[147] Turnbull suggests that kites lifting a man into midair might have been technically feasible, but states that the use of kites to form a human "hang glider" falls squarely in the realm of fantasy.[148] Kuji-kiriKuji-kiri is an esoteric practice which, when performed with an array of hand "seals" (kuji-in), was meant to allow the ninja to enact superhuman feats. The kuji ("nine characters") is a concept originating from Taoism, where it was a string of nine words used in charms and incantations.[149] In China, this tradition mixed with Buddhist beliefs, assigning each of the nine words to a Buddhist deity. The kuji may have arrived in Japan via Buddhism,[150] where it flourished within Shugendō.[151] Here too, each word in the kuji was associated with Buddhist deities, animals from Taoist mythology, and later, Shinto kami.[152] The mudrā, a series of hand symbols representing different Buddhas, was applied to the kuji by Buddhists, possibly through the esoteric Mikkyō teachings.[153] The yamabushi ascetics of Shugendō adopted this practice, using the hand gestures in spiritual, healing, and exorcism rituals.[154] Later, the use of kuji passed onto certain bujutsu (martial arts) and ninjutsu schools, where it was said to have many purposes.[155] The application of kuji to produce a desired effect was called "cutting" (kiri) the kuji. Intended effects range from physical and mental concentration, to more incredible claims about rendering an opponent immobile, or even the casting of magical spells.[156] These legends were captured in popular culture, which interpreted the kuji-kiri as a precursor to magical acts. Foreign ninjaOn February 25, 2018, Yamada Yūji, the professor of Mie University and historian Nakanishi Gō announced that they had identified three people who were successful in early modern Ureshino, including the ninja Benkei Musō (弁慶夢想).[65][157] Musō is thought to be the same person as Denrinbō Raikei (伝林坊頼慶), the Chinese disciple of Marume Nagayoshi.[157] It came as a shock when the existence of a foreign samurai was verified by authorities. Famous people Many famous people in Japanese history have been associated or identified as ninja, but their status as ninja is difficult to prove and may be the product of later imagination. Rumors surrounding famous warriors, such as Kusunoki Masashige or Minamoto no Yoshitsune sometimes describe them as ninja, but there is little evidence for these claims. Some well known examples include:

In popular culture The image of the ninja entered popular culture in the Edo period, when folktales and plays about ninja were conceived. Stories about the ninja are usually based on historical figures. For instance, many similar tales exist about a daimyō challenging a ninja to prove his worth, usually by stealing his pillow or weapon while he slept.[167] Novels were written about the ninja, such as Jiraiya Gōketsu Monogatari, which was also made into a kabuki play. Fictional figures such as Sarutobi Sasuke would eventually make their way into comics and television, where they have come to enjoy a culture hero status outside their original mediums. Ninja appear in many forms of Japanese and Western popular media, including books (Kōga Ninpōchō), movies (Enter the Ninja, Revenge of the Ninja, Ninja Assassin), television (Akakage, The Master, Ninja Warrior), video games (Shinobi, Ninja Gaiden, Tenchu, Sekiro, Ghost of Tsushima), anime (Naruto, Ninja Scroll, Gatchaman), manga (Basilisk, Ninja Hattori-kun, Azumi), Western animation (Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu) and American comic books (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles). From ancient Japan to the modern world media, popular depictions range from the realistic to the fantastically exaggerated, both fundamentally and aesthetically. Gallery

See also

Notes

ReferencesCitations

Sources

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Ninja. |

||||||||||||||||||||||