|

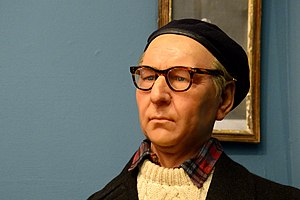

Patrick Kavanagh

Patrick Kavanagh (21 October 1904 – 30 November 1967) was an Irish poet and novelist. His best-known works include the novel Tarry Flynn, and the poems "On Raglan Road" and "The Great Hunger".[1] He is known for his accounts of Irish life through reference to the everyday and commonplace.[2] Life and workEarly lifePatrick Kavanagh was born in rural Inniskeen, County Monaghan, in 1904, the fourth of ten children of James Kavanagh and Bridget Quinn.[3] His grandfather was a schoolteacher called "Kevany",[4][5] which a local priest changed to "Kavanagh" at his baptism. The grandfather had to leave the area following a scandal and never taught in a national school again, but married and raised a family in Tullamore. Patrick Kavanagh's father, James, was a cobbler and farmer. Kavanagh's brother Peter became a university professor and writer, two of their sisters were teachers, three became nurses, and one became a nun. Patrick Kavanagh was a pupil at Kednaminsha National School from 1909 to 1916, leaving in sixth class at the age of 13.[6] He became apprenticed to his father as a shoemaker and worked on his farm. He was also goalkeeper for the Inniskeen Gaelic football team.[7][8] He later reflected: "Although the literal idea of the peasant is of a farm labouring person, in fact a peasant is all that mass of mankind which lives below a certain level of consciousness. They live in the dark cave of the unconscious and they scream when they see the light." He also commented that, although he had grown up in a poor district, "the real poverty was lack of enlightenment [and] I am afraid this fog of unknowing affected me dreadfully."[9] Writing career Kavanagh's first published work appeared in 1928[7] in the Dundalk Democrat and the Irish Independent. Kavanagh had encountered a copy of the Irish Statesman, edited by George William Russell, who published under the pen name AE and was a leader of the Irish Literary Revival. Russell at first rejected Kavanagh's work but encouraged him to keep submitting, and he went on to publish verses by Kavanagh in 1929 and 1930.[9] This inspired the farmer to leave home and attempt to further his aspirations. In 1931, he walked 80 miles (abt. 129 kilometres) to meet Russell in Dublin, where Kavanagh's brother was a teacher.[7][9] Russell gave Kavanagh books, among them works by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Victor Hugo, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Robert Browning, and became Kavanagh's literary adviser.[9] Kavanagh joined Dundalk Library and the first book he borrowed was The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot. Kavanagh's first collection, Ploughman and Other Poems, was published in 1936. It is notable for its realistic portrayal of Irish country life, free of the romantic sentiment often seen at the time in rural poems, a trait he abhorred.[7] Published by Macmillan in its series on new poets,[9] the book expressed a commitment to colloquial speech and the unvarnished lives of real people, which made him unpopular with the literary establishment.[7] Two years after his first collection was published he had yet to make a significant impression. The Times Literary Supplement described him as "a young Irish poet of promise rather than of achievement," and The Spectator commented that, "like other poets admired by A.E., he writes much better prose than poetry. Mr Kavanagh's lyrics are for the most part slight and conventional, easily enjoyed but almost as easily forgotten."[9] In 1938 Kavanagh went to London. He remained there for about five months. The Green Fool, a loosely autobiographical novel, was published in 1938 and Kavanagh was accused of libel.[6] Oliver St. John Gogarty sued Kavanagh for his description of his first visit to Gogarty's home: "I mistook Gogarty's white-robed maid for his wife or his mistress; I expected every poet to have a spare wife." Gogarty, who had taken offence at the close coupling of the words "wife" and "mistress", was awarded £100 in damages.[10] The book, which recounted Kavanagh's rural childhood and his attempts to become a writer, received international recognition and good reviews.[9] However, it was also claimed to be somewhat 'anti-Catholic' in tone, to which Kavanagh reacted by demanding that the work be prominently displayed in Dublin bookshop windows.[11] The Emergency

From "Dark Haired Miriam Ran Away", 1946[12]

The outbreak of World War II (known as The Emergency in the Republic of Ireland) had a damaging effect on the emerging careers of some Irish writers, including Flann O'Brien as well as Kavanagh [13] as they lost access to their publishers in London and reprints of their books could not be arranged. The Republic, which was neutral during the war, shared a border with Northern Ireland (which, as part of the United Kingdom was involved on the Allied side). There were smuggling opportunities on the border, especially in County Monaghan, which would have been more lucrative than writing at this time. [13] In 1939 Kavanagh settled in Dublin. In his biography John Nemo describes Kavanagh's encounter with the city's literary world: "he realized that the stimulating environment he had imagined was little different from the petty and ignorant world he had left. He soon saw through the literary masks many Dublin writers wore to affect an air of artistic sophistication. To him, such men were dandies, journalists, and civil servants playing at art. His disgust was deepened by the fact that he was treated as the literate peasant he had been rather than as the highly talented poet he believed he was in the process of becoming".[9][14] During this time he met John Betjeman who was based in Dublin during the Emergency nominally as a press attaché but also working for British intelligence.[15] Betjeman, impressed by Kavanagh's wide range of social contacts, his ability to get invited to events, and his political ambiguity, tried to recruit him as a British spy.[16] In 1942 he published his long poem The Great Hunger, which describes the privations and hardship of the rural life he knew well. Although it was rumoured at the time that all copies of Horizon, the literary magazine in which it was published, were seized by the Garda Síochána, Kavanagh denied that this had occurred, saying later that he was visited by two Gardaí at his home (probably in connection with an investigation of Horizon under the Special Powers Act).[13] Written from the viewpoint of a single peasant against the historical background of famine and emotional despair, the poem is often held by critics to be Kavanagh's finest work. It set out to counter the saccharine romanticising of the Irish literary establishment in its view of peasant life. Richard Murphy in The New York Times Book Review described it as "a great work" and Robin Skelton in Poetry praised it as "a vision of mythic intensity".[9] Post-warKavanagh worked as a part-time journalist, writing a gossip column in the Irish Press under the pseudonym Piers Plowman from 1942 to 1944 and acted as film critic for the same publication from 1945 to 1949. In 1946 the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, found Kavanagh a job at the Catholic magazine The Standard. McQuaid continued to support him throughout his life.[17] Tarry Flynn, a semi-autobiographical novel, was published in 1948 and was banned for a time.[7] It is a fictional account of rural life. It was later made into a play, performed at the Abbey Theatre in 1966. In late 1946 Kavanagh moved to Belfast, where he worked as a journalist and as a barman in a number of public houses in the Falls Road area. During this period he lodged in the Beechmount area in a house where he was related to the tenant through the tenant's brother-in-law in Ballymackney, County Monaghan. Before returning to Dublin in November 1949 he presented numerous manuscripts to the family, all of which are now believed to be in Spain. Kavanagh's personality became progressively quixotic as his drinking increased over the years and his health deteriorated. Eventually becoming a dishevelled figure, he moved among the bars of Dublin, drinking whiskey and displaying his predilection for turning on benefactors and friends.[18] Later career In 1949 Kavanagh began to write a monthly "Diary" for Envoy, a literary publication founded by John Ryan, who became a lifelong friend and benefactor. Envoy's offices were at 39 Grafton Street, but most of the journal's business was conducted in a nearby pub, McDaid's, which Kavanagh subsequently adopted as his local. Through Envoy he came into contact with a circle of young artists and intellectuals including Anthony Cronin, Patrick Swift, John Jordan and the sculptor Desmond MacNamara, whose bust of Kavanagh is in the Irish National Writers Museum. Kavanagh often referred to these times as the period of his "poetic rebirth".[19] In 1952 Kavanagh published his own journal, Kavanagh’s Weekly: A Journal of Literature and Politics, in conjunction with, and financed by, his brother Peter. It ran to some 13 issues, from 12 April to 5 July 1952.[6]  The Leader lawsuit and lung cancerIn 1954 two major events changed Kavanagh's life. First, he issued libel proceedings against a magazine called The Leader for publishing an anonymously-written profile of him as an alcoholic sponger.[20] Kavanagh had made numerous enemies in his film and literary criticism and had written diatribes against the Civil Service, the Arts Council, the Irish Language movement so there were many possible authors of the piece.[20] Based on his previous experience of libel, he believed he would get an out-of-court settlement. However, the magazine hired former (and future) Taoiseach and Attorney General (1926–1932) John A. Costello as their barrister, who won the case when it came to trial.[6] Second, shortly after Kavanagh lost this case, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and was admitted to hospital, where he had a lung removed.[7] It was while recovering from this operation by relaxing on the banks of the Grand Canal in Dublin that Kavanagh rediscovered his poetic vision. He began to appreciate nature and his surroundings, and took his inspiration from them for many of his later poems.[7] Costello and Kavanagh eventually became good friends,[9] with Kavanagh remarking that he voted for him after the trial. Turning point: Kavanagh begins to receive acclaimIn 1955 Macmillan rejected a typescript of poems by Kavanagh, which left the poet very depressed.[21] Patrick Swift, on a visit to Dublin in 1956, was invited by Kavanagh to look at the typescript. Swift then arranged for the poems to be published in the English literary journal Nimbus[22](19 poems were published). This proved a turning point and Kavanagh began receiving the acclaim that he had always felt he deserved. His next collection, Come Dance with Kitty Stobling, was directly linked to the mini-collection in Nimbus.[23] Between 1959 and 1962 Kavanagh spent more time in London, where he contributed to Swift's X magazine.[24] During this period Kavanagh occasionally stayed with the Swifts in Westbourne Terrace.[25] He gave lectures at University College Dublin and in the United States,[7] represented Ireland at literary symposiums, and became a judge of the Guinness Poetry Awards. In London, he often stayed with his publisher, Martin Green, and Green's wife Fiona, in their house in Tottenham Street, Fitzrovia. It was at this time that Martin Green produced Kavanagh's Collected Poems (1964) with prompting from Patrick Swift and Anthony Cronin".[26] In the introduction Kavanagh wrote: "A man innocently dabbles in words and rhymes, and finds that it is his life." Marriage and death Kavanagh married his long-term companion Katherine Barry Moloney (niece of Kevin Barry) in April 1967 and they set up home together on Waterloo Road in Dublin.[6][7] Kavanagh fell ill at the first performance of Tarry Flynn by the Abbey Theatre company in Dundalk Town Hall and died a few days later, on 30 November 1967, in Dublin.[7] His grave is in Inniskeen adjoining the Patrick Kavanagh Centre. His wife Katherine died in 1989; she is also buried there. LegacyNobel Laureate Séamus Heaney is acknowledged to have been influenced by Kavanagh.[27] Heaney was introduced to Kavanagh's work by the writer Michael McLaverty when they taught together at St Thomas's, Belfast. Heaney and Kavanagh shared a belief in the capacity of the local, or parochial, to reveal the universal.[28] Heaney once said that Kavanagh's poetry "had a transformative effect on the general culture and liberated the gifts of the poetic generations who came after him." Heaney noted: "Kavanagh is a truly representative modern figure in that his subversiveness was turned upon himself: dissatisfaction, both spiritual and artistic, is what inspired his growth.... His instruction and example helped us to see an essential difference between what he called the parochial and provincial mentalities". As Kavanagh put it: "All great civilizations are based on the parish". He concludes that Kavanagh's poetry vindicates his "indomitable faith in himself and in the art that made him so much more than himself".[29]   The actor Russell Crowe has stated that he is a fan of Kavanagh. He commented: "I like the clarity and the emotiveness of Kavanagh. I like how he combines the kind of mystic into really clear, evocative work that can make you glad you are alive". On 24 February 2002, after winning the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role for his performance in A Beautiful Mind, Crowe quoted Kavanagh during his acceptance speech at the 55th British Academy Film Awards. When he became aware that the Kavanagh quote had been cut from the final broadcast, Crowe became aggressive with the BBC producer responsible, Malcolm Gerrie.[30] He said: "it was about a one minute fifty speech but they've cut a minute out of it".[31] The poem that was cut was a four-line poem: To be a poet and not know the trade, When the Irish Times compiled a list of favourite Irish poems in 2000, ten of Kavanagh's poems were in the top 50, and he was rated the second favourite poet behind W. B. Yeats. Kavanagh's poem "On Raglan Road", set to the traditional air "Fáinne Geal an Lae", composed by Thomas Connellan in the 17th century, has been performed by numerous artists as diverse as Van Morrison, Luke Kelly, Mark Knopfler, Billy Bragg, Sinéad O'Connor, Joan Osborne and many others. There is a statue of Kavanagh beside Dublin's Grand Canal, inspired by his poem "Lines written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin": O commemorate me where there is water This statue is featured in the short film Yu Ming Is Ainm Dom, about a Chinese man who learns Irish in order to live in Ireland. Every 17 March, after the St Patrick's Day parade, a group of Kavanagh's friends gather at the Kavanagh seat on the banks of the Grand Canal at Mespil road in his honour. The seat was erected by his friends, led by John Ryan and Denis Dwyer, in 1968.[32] A bronze sculpture of the writer stands outside the Palace Bar on Dublin's Fleet Street.[33] There is also a statue of Patrick Kavanagh located outside the Irish pub and restaurant, Raglan Road, at Walt Disney World's Downtown Disney in Orlando, Florida. His poetic tribute to his friend the Irish American sculptor Jerome Connor was used in the plaque overlooking Dublin's Phoenix Park dedicated to Connor. The Patrick Kavanagh Poetry Award is presented each year for an unpublished collection of poems. The annual Patrick Kavanagh Weekend takes place on the last weekend in September in Inniskeen, County Monaghan, Ireland. The Patrick Kavanagh Centre, an interpretative centre set up to commemorate the poet, is located in Inniskeen. Kavanagh Archive

From "The Self-Slaved"

In 1986, Peter Kavanagh negotiated the sale of Patrick Kavanagh's papers as well as a large collection of his own work devoted to the late poet to University College Dublin. The purchase was enabled by a public appeal for funds by the late Professor Gus Martin. Peter included in the sale his original hand press which he had built.[34] The archive is housed in a special collections room in UCD's library, and the hand press is on loan to the Patrick Kavanagh Centre, Inniskeen. The contents include:[34]

Peter Kavanagh's papers include thesis, plays, autobiographical writing, printed material, personal and general correspondence memorabilia, tape recordings, galley proofs (1941–82) and family memorabilia (1872–1967). CopyrightOwnership of the copyright is vested in the Trustees of The Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Trust by virtue of the terms of the will of the late Kathleen Kavanagh, widow of the poet, who in turn became entitled to the copyright on the death of her husband. The proceeds of the trust are used to support deserving writers. The Trustees are Patrick MacEntee, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, and Eunan O'Halpin.[35] This was disputed by the late Peter Kavanagh who continued publishing his work after Patrick's death. This dispute led some books to go out of print. Most of his work is now available in the UK and Ireland but the status in the United States is more uncertain. WorksPoetry

Prose

Dramatisations

References

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Patrick Kavanagh.

|

||||||||||||||||||