|

Picnic on the Grass

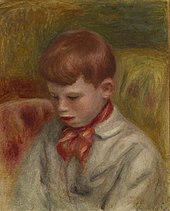

Picnic on the Grass (French: Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe) is a 1959 French comedy film written and directed by Jean Renoir, starring Paul Meurisse, Fernand Sardou and Catherine Rouvel. It is known in the United Kingdom by its original title or in translation as Lunch on the Grass. A satire on contemporary science and politics, it revolves around a prominent biologist and politician who wants to replace sex with artificial insemination, but begins to reconsider when a picnic he organizes is interrupted by the forces of nature. The film brings up issues of modernity, human reproduction, youth and European integration. It ridicules rationalist idealism and celebrates a type of materialism it associates with classical mythology and ancient Greek philosophy. The title is taken from the painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe by Édouard Manet. The female lead in Picnic on the Grass was the first major role for Rouvel, who due to an unusual contract would not appear in another film until 1963. Filming took place around Renoir's childhood home in Provence, and inspiration came from the impressionist paintings of his father, Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The filming technique was influenced by live television and involved multiple cameras and direct audio recording. The press reviews were generally positive and described the film as charming and beautiful. Negative response came from the political left, where critics disapproved of the film's treatment of progress and depiction of a European superstate; the subject of European unification was topical and sensitive due to the creation of the European Economic Community in 1957. In spite of the generally good reviews, the film was a commercial failure, and has attracted little attention from general audiences over the years. Some later critics have seen its critiques of technocracy and dogged rationalism as both prophetic and of increasing relevance. PlotThe famous French biologist Étienne Alexis is the frontrunner in the upcoming election for the first President of Europe. He advocates mandatory artificial insemination in order to improve humanity and make it worthy of modern science. He is newly engaged to his German cousin Marie-Charlotte and has invited her to a picnic near his mansion in Provence. Nénette, a farmer's daughter, is disappointed with men after a failed relationship, but still wants children and applies to be a test subject for Étienne's insemination project. She ends up hired as his chambermaid and accompanies the picnic with the other servants. Present at the picnic are several cousins of the engaged couple—stiff, rationally minded people who profess belief in scientific progress. They have invited journalists to document the picnic event, which they want to present as a symbol for the new unified Europe. The picnic takes place next to the ruins of a temple of Diana, the goddess who the ancient Romans believed presided over childbirth. Nearby is also a group of young campers. Nénette is worried when she spots the goatherd Gaspard; she knows that when he plays his flute, strange things tend to happen. Gaspard plays and suddenly a strong wind blows away the picnic chairs and tables. As everybody takes cover, Étienne and Nénette are separated from the rest. When the wind subsides, the two are invited to sit down with the campers, to whom Étienne explains how he hopes to eliminate passion. Meanwhile, a Bacchanalia breaks out among the picnic guests not far away. Leaving the campers to look for Marie-Charlotte, Étienne ends up seeing Nénette swimming nude, and becomes visibly affected; when Nénette emerges from the water and joins him, Gaspard's flute is heard playing again, and the two run off into the high reeds together. After returning, they see the cousins and servants leaving in cars. They choose to not approach them, and instead rejoin the campers, who offer to let them stay the night in their camp. The next morning, Étienne says he wants to escape from the world for a while, so he and Nénette go to stay at Nénette's father Nino's house. Étienne begins to reconsider the relationship between humans and the natural world. The cousins eventually discover his whereabouts and arrive at the house, where they convince Nénette to leave. Realizing she is gone, Étienne becomes agitated and goes to look for her, running into Gaspard, the goatherd, who recommends that he kneel before his goat and ask for help. After doing so, Étienne turns ecstatic and shouts "Down with science!" before being forcibly restrained by his cousins. Étienne goes back to his old life, but on the day of his wedding he discovers Nénette, happily pregnant with his child, working in a hotel kitchen. He abruptly brings her instead of Marie-Charlotte to the waiting crowd. He will launch his presidential campaign with a speech about science and nature, and he intends to marry Nénette. CastCast adapted from A Companion to Jean Renoir and the British Film Institute.[1]

ThemesModernity and nature The themes of Picnic on the Grass revolve around modern issues such as artificial insemination, the pharmaceutical industry and the mass media. Jean Renoir's biographer Pascal Mérigeau writes that the film "deals with disturbingly serious subjects using a farcical tone".[2] The film historian Jean Douchet wrote that the film should be taken seriously, but describes its story as an invitation to not do so.[3] Renoir satirizes a modernity he does not think highly of, and uses story and tone to suggest to the viewer that it is not very important.[4] The central conflict is built on several dichotomies: between the Apollonian and Dionysian, the technocratic Northern Europe and underdeveloped Mediterranean region, and the rationalist idealism of Postchristianity and materialist philosophy of ancient Greece.[5] The film ridicules the idealist notion of progress and celebrates the Dionysian world.[6] It portrays an empty spirituality produced by a bureaucratic utilitarianism, and thereby seeks to justify the celebration of a material world imbued with spirit.[7] When Étienne converses with a Christian priest, the two are shown to have disagreements, but to simultaneously understand each other well; this is because both still belong to the idealist side in the film's conflict.[6] According to Douchet, the film sets up a scenario where harmonious equilibrium is achieved when science abandons idealism and submits to a materialist view of nature. This happens when Étienne marries Nénette, who is pregnant with their naturally conceived child.[8] Étienne is an intellectual who lives in a theoretical world. This makes him similar to the main characters in two earlier works by Renoir: the play Orvet (1955) and the television film The Doctor's Horrible Experiment (1959).[9] Étienne's eugenic ideology combines rationalism and moralism in a way that gives Darwinism an active role in concord with individualism. Human reproduction and evolution become tied to Étienne's notions of self-sufficiency and to ideas about social responsibility.[10] Nénette is comfortable with her human physicality, but is also driven by self-sufficiency in her wish to have her own child through artificial insemination. She is emancipated and mobile, and it is her actions that twice bring her to Étienne. Another—militaristic—type of women's emancipation is represented by Marie-Charlotte.[11] Allied against Western rationalism are the gods Pan and Diana. Pan is evoked through the flute-playing goatherd, and Diana presides over chastity and childbirth, which in this classical mythological context are aspects of female independence.[11] Youth and experience Renoir had spent years of his childhood and adolescence in the area where Picnic on the Grass was filmed.[2] He had recently begun to write a book about his father, the painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, which made him reminisce about his early life.[12] According to Mérigeau, the film sees Renoir return to the perspective he had as a young boy and adolescent, from where he confronts the troubling questions of the contemporary world. Renoir's reconnection to his younger self is paralleled in the mode of storytelling, which is reminiscent of the silent cinema in which he began his filmmaking career in the 1920s; Mérigeau writes that the film thereby creates a paradox, since it was made using new techniques from television. Another parallel to Renoir's earlier experiences is how the portrayal of eroticism is similar to that of his 1936 film Partie de campagne.[2] The filmmaker Shirley Clarke said that Picnic on the Grass "could only have been made by someone of 6 or 60".[13] European integrationThe historian Hugo Frey groups Picnic on the Grass with a number of French comedies that deal with a "modernist invasion".[14] These include the films of Jacques Tati, Mr. Freedom (1968), directed by William Klein, and The Holes (1974), directed by Pierre Tchernia. Renoir's film stands out in the group because it targets the nascent European Union rather than the United States.[15] The vision of a European superstate was conceived as the logical continuation of the European Economic Community (EEC), created in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome. The film's depiction of a French and German elite couple follows a convention where European integration is understood as something that particularly concerns France and Germany, or France and Germanic-speaking Europe overall. The way Étienne speaks to journalists, with technical and obscure terminology, envisions a future political elite as the only people who will comprehend the European project.[16] ProductionDevelopmentAfter working in Hollywood in the 1940s, Renoir had re-established himself in European cinema following the international success of The River (1951). During the 1950s, he developed a more detached and depoliticized approach to filmmaking than before. Simultaneously, he became a more prominent celebrity in France due to television appearances and an increased appreciation for his films from the 1930s. His work became more oriented toward personal subjects.[17] The title of Picnic on the Grass is taken from the painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) by Édouard Manet.[12] Renoir wrote seven versions of the screenplay.[18] He made the film through his own production company, Compagnie Jean Renoir; it was the last time he did so, as annoyances about logistics during the production made him decide to never produce his own films again. Financial backing was provided by Pathé and the UCIF, to whom Renoir also offered 50% of his earnings from La Grande Illusion (1937) as a reimbursement guarantee, to a limit of 10 million francs.[2] Pre-productionCatherine Rouvel—who was married to Georges Rouveyre—had her first major role in Picnic on the Grass. Renoir had met her in 1958, shortly after her 19th birthday, during a tribute to Robert J. Flaherty at the Cinémathèque Française. She had accompanied her husband Georges Rouveyre, whose friend Claude Beylie, a film critic, introduced her to Renoir. A few weeks earlier, she had enrolled at the drama school Centre d'art dramatique de la rue Blanche, and that same winter, Renoir contacted her for a reading and an informal screen test.[19] Later, when the casting process for Picnic on the Grass formally began, she was not the only candidate for the role of Nénétte; Renoir auditioned Michèle Mercier the same day, and also considered giving the part to the dancer Ludmilla Tchérina, whom he had directed in a ballet. Renoir told Rouveyre in April 1959 that the role was hers; soon thereafter, he suggested that she should change her name to Rouvel.[20] For the male lead, Renoir first considered Pierre Blanchar, a man in his mid 60s, before giving the role to the 20-years-younger Paul Meurisse; Renoir had previously worked with Meurisse in a production of Julius Caesar and the two were good friends.[20] In the role of the goatherd Gaspard he cast Charles Blavette, who had played the title role in Renoir's film Toni (1935).[21] Renoir rehearsed with the actors for a week before adding technicians to the rehearsals. After this, the director, designer, camera operator and assistant scouted the filming locations. The rehearsals then resumed, with markers chalked on the floor of the rehearsal room corresponding to the filming locations' topography.[22] Working with markers was something Renoir abandoned after Picnic on the Grass, because he thought it was better if the actors could discover the surroundings more freely.[23] Filming and post-production Filming took place from 6 to 30 July 1959 at Studio Francœur in Paris, and in Cagnes-sur-Mer and La Gaude in Alpes-Maritimes.[25] Picnic on the Grass borrows visual traits from French impressionist painting, in particular that of Pierre-Auguste Renoir. This is reflected in the choices of filming locations; Jean Renoir called the film "something of a homage to the olive-trees under which my father worked so much".[21] A major location was the property Les Collettes in Cagnes-sur-Mer, which Renoir the elder had bought in 1907, and which had been the home of Jean Renoir for a part of his childhood and adolescence.[26] Renoir the elder had spent significant time in the town La Gaude where a part of the film was shot, and several of his paintings feature the nearby river Le Coup, which also appears in the film.[21] Another stylistic choice came from the director's desire to follow impulses on location and encourage improvisation; Renoir said he wanted to make a "sort of filmed poem" written in one sitting.[22] After the rehearsals, he gave very little instruction to the actors.[22] He used a rapid working method influenced by live television,[2] a technique he had first used in his recent television film The Doctor's Horrible Experiment, which he called an "experimental film".[27] He also took advantage of the cinematographer's experience from making newsreel footage, with six cameras placed around a scene to cover all useful angles and shots.[22] In addition to saving time and money, the aim was to retain the uninterrupted, intensive acting of a long take and still be able to make cuts within the scene.[28] This method made it possible to record most of the dialogue directly, without problems of continuity due to surrounding sounds such as that from airplanes. Up to twelve microphones were present and only around 20 phrases had to be dubbed in post-production.[22] Several key crew members were reused from The Doctor's Horrible Experiment. They included the cinematographer Georges Leclerc and the editor Renée Lichtig, both of whom would work with Renoir again on his next film, The Elusive Corporal, which became his final feature film,[2] although the multiple-camera technique was abandoned after Picnic on the Grass.[29] The original music for Picnic on the Grass was composed by Joseph Kosma, who first collaborated with Renoir in 1936 and had provided music for several of his best known films.[30] The score includes a melody the goatherd plays in high pitch on his flute during the wind scene, an upbeat piece played on clarinet in jazz style, and a melody played on flute with harp glissandos during a lyrical passage.[31] ReleasePathé released Picnic on the Grass theatrically in France on 11 November 1959.[32] In the United Kingdom it was released by Mondial Films in April 1960 under the title Lunch on the Grass.[33] It was released in the United States as Picnic on the Grass on 12 October 1960 by Kingsley-International Pictures.[32] For the French home-media market, it was first released on VHS in 1990 by Fil à film and on DVD in 2003 by StudioCanal vidéo. The DVD, which was re-released in 2008, includes a 30-minute documentary directed by Pierre-François Glaymann.[34] The film was released on DVD in the United Kingdom in 2007 by Optimum Releasing, as part of a box set with other Renoir films. The DVD uses the original French title, Le Déjeuner Sur L'Herbe.[35] ReceptionContemporary critical responseFrench film critics generally gave Picnic on the Grass a positive reception, characterized by respect for Renoir. They highlighted the film's connection to impressionism and described it as charming.[36] Rouvel's face was on the cover of the December 1959 issue of Cahiers du cinéma, and the magazine called the film "the most beautiful of a month rich in masterpieces".[37][a] The review by Éric Rohmer stressed the technical novelty of the film, released in "the year of the 'New Wave'", which Renoir had influenced profoundly.[38][b] With its detached and intentionally naive style, Rohmer described it as "avant-garde popular theater" in the vein of Mr Puntila and his Man Matti.[39][c] For Rohmer, the satire against science should be understood through Renoir's role as an artist, not philosopher or moralist, and not as a rejection of practical science.[40] As for politics, he defended the artist's right to look at the problems of the world without being politically engaged.[41] Picnic on the Grass made 13th place on Cahiers du cinéma's composite list of the best films of 1959.[42] Pierre Braunberger, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Rohmer and François Truffaut were among the Cahiers critics who named it to year-end top ten lists.[43]  Renoir had supported the French Communist Party (PCF) in the 1930s, but Picnic on the Grass received negative reviews from critics with communist sympathies. It was released at a time when the PCF idealized progress and its members were enthusiastic about the Soviet space program.[44] Samuel Lachize of L'Humanité considered the film flawed on a technical level, and criticized its lack of a clear choice between scientific progress and the rejection of it. He dismissed the philosophical content, which he took as a pseudo-Rousseauesque message about going back to nature.[45] The Doctor's Horrible Experiment received a similar treatment from communist critics.[46] Left-wing critics also criticized Picnic on the Grass for its evident acceptance of a European superstate, which was taken as an approval of the EEC, opposed by the left at the time. Furthermore, upsetting for the left, the reservations Étienne appears to have developed toward the end of the film were interpreted as support for Charles de Gaulle's Europe des patries ("Europe of fatherlands").[47] In the 1970s, the film critic Raymond Durgnat related the response to the left's own struggle to oppose the EEC without turning to patriotism. Durgnat wrote that it was "perhaps not too unkind to suggest that my left-wing colleagues were making their 'lost leader' a scapegoat for the very real difficulties of the left itself—or should one say the lefts themselves?"[48] Gideon Bachmann wrote in Film Quarterly that many American critics gave Picnic on the Grass a "silly treatment", because they did not understand it through its director as a person.[49] He used Hollis Alpert of the Saturday Review as a positive counterexample.[49] Alpert called it "a nonsensically unconventional movie" where viewers "would be better off not trying to make sense or logic out of it, but simply allowing M. Renoir to have his day in the fields".[50] Bachmann wrote that the film is reminiscent of Tati's films, both in message and how the message is conveyed through colors.[49] He contrasted the seeming simplicity with the serious content, and the impressionism with the surreal elements. He called it "almost facile in impact but lasting in the perturbations it causes".[51] Retrospective critical responsePicnic on the Grass has received little attention from general audiences over time, but it has been embraced by individual critics.[18] In 2006, Luc Arbona of Les Inrockuptibles called it an "extraordinary pamphlet" portraying "the peddlers of progress" who "only care about security, asepticity and uniformity".[52][d] Arbona called the satire "abundant and exhilirating" and the film "brilliantly prophetic", because by the time of his writing, Arbona wrote, "these progress-obsessed, these ad-agency apostles who have nothing but the politically correct to say, have seized power and are leading the dance."[52][e] The New Yorker's Richard Brody wrote about the film in conjunction with Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Taking its message as a rejection of modern technology, he compared it favorably to Steven Soderbergh's Contagion, which shows science and the government triumphant in a crisis of natural origin. Brody made a point of separating art and politics: "Looking to filmmakers for practical advice in the teeth of trouble is usually as pointless as turning to politicians for visions of beauty."[53] Time Out called it "one of Renoir's most ravishing, and simultaneously most irritating films", because the "sumptuous photography" repeatedly "collapses into cold argument".[54] Box officePicnic on the Grass had 757,024 admissions in France,[55] and was a commercial failure. Renoir addressed this in a letter to the producer Ginette Doynel a few weeks after the Paris premiere. He wrote that the failure had given him a distaste for film and television work in general; from now on, he would instead focus on his teaching position at the University of California, Berkeley, his plays, and his book about his father.[18] Picnic on the Grass later had a significant theatrical run in the United States, which delighted him.[56] LegacyRouvel signed an unusual contract which had the practical effect of giving Renoir the power to approve all her engagements for the next three years. Renoir decided to keep her away from the film industry and only accepted offers of theater roles. He rejected roles for her in The Green Mare and a film by Gérard Oury. Rouvel returned to film acting in Claude Chabrol's Bluebeard, released in January 1963.[57] The film Le Bonheur (1965), directed by Agnès Varda, pays tribute to Picnic on the Grass by including a passage which plays on a television screen.[58] The film scholar Nancy Pogel argues in her book on Woody Allen that Allen's A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy (1982) is indebted to Picnic on the Grass.[59] See also

ReferencesOriginal quotations

Notes

Sources

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||