|

Predicate (grammar)

The term predicate is used in two ways in linguistics and its subfields. The first defines a predicate as everything in a standard declarative sentence except the subject, and the other defines it as only the main content verb or associated predicative expression of a clause. Thus, by the first definition, the predicate of the sentence Frank likes cake is likes cake, while by the second definition, it is only the content verb likes, and Frank and cake are the arguments of this predicate. The conflict between these two definitions can lead to confusion.[1] SyntaxTraditional grammarThe notion of a predicate in traditional grammar traces back to Aristotelian logic.[2] A predicate is seen as a property that a subject has or is characterized by. A predicate is therefore an expression that can be true of something.[3] Thus, the expression "is moving" is true of anything that is moving. This classical understanding of predicates was adopted more or less directly into Latin and Greek grammars; from there, it made its way into English grammars, where it is applied directly to the analysis of sentence structure. It is also the understanding of predicates as defined in English-language dictionaries. The predicate is one of the two main parts of a sentence (the other being the subject, which the predicate modifies).[a] The predicate must contain a verb, and the verb requires or permits other elements to complete the predicate, or else precludes them from doing so. These elements are objects (direct, indirect, prepositional), predicatives, and adjuncts:

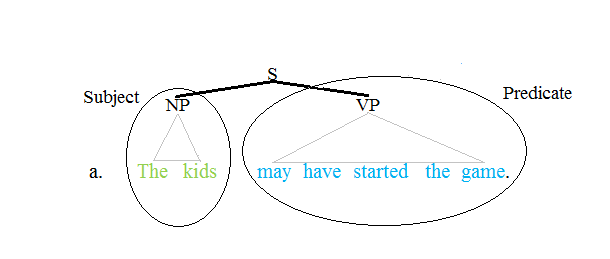

The predicate provides information about the subject, such as what the subject is, what the subject is doing, or what the subject is like. The relation between a subject and its predicate is sometimes called a nexus. A predicative nominal is a noun phrase: in the sentence George III is the king of England, the phrase the king of England is the predicative nominal. In English, the subject and predicative nominal must be connected by a linking verb, also called a copula. A predicative adjective is an adjective, such as in Ivano is attractive, attractive being the predicative adjective. The subject and predicative adjective must also be connected by a copula. Modern theories of syntaxSome theories of syntax adopt a subject-predicate distinction. For instance, a textbook phrase structure grammar typically divides an English declarative sentence (S) into a noun phrase (NP) and verb phrase (VP).[4] The subject NP is shown in green, and the predicate VP in blue. Languages with more flexible word order (often called nonconfigurational languages) are often also treated differently in phrase structure approaches.[citation needed] On the other hand, dependency grammar rejects the binary subject-predicate division and places the finite verb as the root of the sentence. The matrix predicate is marked in blue, and its two arguments are in green. While the predicate cannot be construed as a constituent in the formal sense, it is a catena. Barring a discontinuity, predicates and their arguments are always catenae in dependency structures.[5] Some theories of grammar accept both a binary division of sentences into subject and predicate while also giving the head of the predicate a special status. In such contexts, the term predicator is used to refer to that head.[6] Non-subject predicandsThere are cases in which the semantic predicand has a syntactic function other than subject. This happens in raising constructions, such as the following:

Here, you is the object of the make verb phrase, the head of the main clause, but it is also the predicand of the subordinate think clause, which has no subject.[7]: 329–335 Semantic predicationThe term predicate is also used to refer to properties and to words or phrases which denote them. This usage of the term comes from the concept of a predicate in logic. In logic, predicates are symbols which are interpreted as relations or functions over arguments. In semantics, the denotations of some linguistic expressions are analyzed along similar lines. Expressions which denote predicates in the semantic sense are sometimes themselves referred to as "predication".[8] Carlson classesThe seminal work of Greg Carlson distinguishes between types of predicates.[9] Based on Carlson's work, predicates have been divided into the following subclasses, which roughly pertain to how a predicate relates to its subject. Stage-level predicatesA stage-level predicate is true of a temporal stage of its subject. For example, if John is "hungry", then he typically will eat some food. His state of being hungry therefore lasts a certain amount of time, and not his entire lifespan. Stage-level predicates can occur in a wide range of grammatical constructions and are probably the most versatile kind of predicate. Individual-level predicatesAn individual-level predicate is true throughout the existence of an individual. For example, if John is "smart", this is a property that he has, regardless of which particular point in time we consider. Individual-level predicates are more restricted than stage-level ones. Individual-level predicates cannot occur in presentational "there" sentences (a star in front of a sentence indicates that it is odd or ill-formed):

Stage-level predicates allow modification by manner adverbs and other adverbial modifiers. Individual-level predicates do not, e.g.

When an individual-level predicate occurs in past tense, it gives rise to what is called a lifetime effect: The subject must be assumed to be dead or otherwise out of existence.

Kind-level predicatesA kind-level predicate is true of a kind of a thing, but cannot be applied to individual members of the kind. An example of this is the predicate are widespread. One cannot meaningfully say of a particular individual John that he is widespread; one may only say this of kinds, as in

Certain types of noun phrases cannot be the subject of a kind-level predicate. We have just seen that a proper name cannot be. Singular indefinite noun phrases are also banned from this environment:

Collective vs. distributive predicatesPredicates may also be collective or distributive. Collective predicates require their subjects to be somehow plural, while distributive ones do not. An example of a collective predicate is "formed a line". This predicate can only stand in a nexus with a plural subject:

Other examples of collective predicates include meet in the woods, surround the house, gather in the hallway and carry the piano together. Note that the last one (carry the piano together) can be made non-collective by removing the word together. Quantifiers differ with respect to whether or not they can be the subject of a collective predicate. For example, quantifiers formed with all the can, while ones formed with every or each cannot.

See alsoNotes

References

Literature

External links

|