|

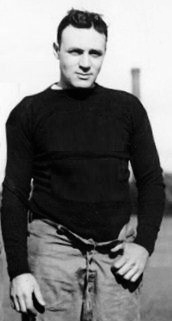

Ralph Horween

Ralph Horween (born Ralph Horwitz; also known as Ralph McMahon or B. McMahon; August 3, 1896 – May 26, 1997) was an American football player and coach. He played fullback and halfback and was a punter and drop-kicker for the unbeaten Harvard Crimson football teams of 1919 and 1920, which won the 1920 Rose Bowl. He was voted an All-American. Horween played three seasons in the National Football League (NFL), for the Racine Cardinals/Chicago Cardinals. In addition, he was an assistant coach for the Cardinals during his playing years. His brother, Arnold Horween, was also an All-American football player for Harvard, and also played in the NFL for the Cardinals. They were the last Jewish brothers to play in the NFL until Geoff Schwartz and Mitchell Schwartz, in the 2000s. After retiring from football, Horween attended Harvard Law School, and became a patent attorney, and later a federal government official. He was also a successful businessman, as he raised cattle and helped run the family leather tannery business, Horween Leather Company. He was the first NFL player to live to the age of 100.[1] Early and personal life Horween's Jewish parents, Isidore and Rose (Rabinoff), immigrated to Chicago from Ukraine in the Russian Empire in 1892.[2][3][4] His family changed its name during his youth to Horween from its original name, which was either Horwitz or Horowitz.[5][6][7][8] Horween was born in Chicago.[8][9] He was the brother of Arnold Horween, who was two years younger.[10] The Horween brothers were the last Jewish brothers to play in the NFL until offensive tackles Geoff Schwartz and Mitchell Schwartz in the 2000s.[11][12] Horween played high school football at Francis W. Parker School.[4][13] He was 5' 10" (1.78 m), and weighed 200 pounds (91 kg).[14] He eloped and married Genevieve Brown (born March 4, 1901) in October 1924; they were married for 64 years until her death on November 25, 1987.[3][6] They moved to Cismont, Virginia, in 1952, and later to Charlottesville, Virginia.[15] He had two sons, Ralph Stow and Frederick Stow.[15] College and Navy careerHorween played fullback and halfback in the backfield, the two running back positions, and was known as a good punter and drop-kicker, at Harvard University for the Harvard Crimson. He was an All-American.[13][16][17][18][19][20] He was described as a "line plunger" of "tremendous power."[21] On November 11, 1916, he kicked a 35-yard (32 m) field goal to lead Harvard over previously unbeaten Princeton, 3–0.[22] That year, he was named Walter Camp All-America honorable mention at fullback, and New York Times All-East honorable mention.[14] During World War I, he enlisted and was a Junior Lieutenant in the United States Navy, on active duty from April 1917 to July 1919.[23][24] He attended cadet school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and served on the patrol vessel USS Talofa, the battleship USS Connecticut, the destroyer USS Maury, and the destroyer USS Gregory.[23][25] In both 1919 and 1920 Harvard was undefeated (9–0–1, as they outscored their competition 229–19, and 8–0–1, respectively).[14][26][27] In 1919, Donald Grant Herring ranked Horween the Third-Team center on the Princeton-Yale-Harvard composite team, and opined that if he had played regularly at center for the entire season he might have been the number one choice, and the New York Times named him All-East honorable mention.[14][21] Horween was part of the unbeaten Harvard football team that won the 1920 Rose Bowl against Oregon, 7–6.[18][28][29] Horween sustained a chipped collarbone and dislocated shoulder in the victory.[30][31] It remain's the only bowl game appearance in Harvard football history.[32] He graduated with an A.B. in May 1920.[33] Professional football careerHe played 22 career games in the National Football League.[14] Playing under the alias of the Irish name Ralph McMahon or B. McMahon or R. McMahon,[6][8][18][34][35] Horween started playing professional football a year after the NFL was founded, and played for the Cardinals for three years (first as they were called the Racine Cardinals, in the American Professional Football Association, the predecessor to the NFL).[36] He played for the renamed Chicago Cardinals from 1921 to 1923.[18] He was paid $40 ($700 in current dollar terms) a week.[37] His brother Arnold teamed up with him, playing for the Cardinals as well.[18] On November 30, 1922, he kicked a 34-yard (31 m) field goal as the Cardinals beat the Chicago Staleys 6–0.[35] On October 7, 1923, he and his brother both scored in the same game, as he ran for a touchdown and his brother kicked two extra points as the Cardinals beat the Rochester Jeffersons 60–0 at Normal Park in Chicago.[22] On December 2, 1923, they did it again, as ran for a touchdown and his brother kicked a 35-yard (32 m) field goal as the Cardinals beat the Oorang Indians 22–19.[22] In 1923, his brother became head coach of the Cardinals and Ralph joined him as an assistant coach, as both continued to play as well.[14][32] He played in 11 games that season as the team went 8–4–0.[14] He was paid $275 ($4,900 in current dollar terms) for a late season game, and used it to buy an engagement ring and elope.[6] He retired following the 1923 season.[14] Life after footballHarvard Law School, and law careerAfter retiring from football, Horween returned to Harvard Law School, where he wrote "The Effect of Certain Types of State Statutes Upon the Criteria, in the Federal Courts, of the Adequacy of the Remedy at Law as a Basis for Federal Equity Jurisdiction", which was published by the law school in 1929.[38] He earned an LL.B. law degree in 1929, and that year became a member of the Illinois State Bar and a patent attorney.[18][39][40][41] He later had a successful law practice in Chicago, known as Topliff, Horween & Merrick from 1940 to 1942, and Topliff & Horween after 1942.[3][18][19][42] He was also a successful businessman, as he raised cattle and helped run a family business that supplied the leather for the footballs used in the NFL.[18][41] He served as chief of the Chicago office of the federal Petroleum Administrative Board that administered crude oil permits, and was a special assistant federal attorney who handled prosecutions of oil code violations.[18][43][44][45] Horween served as Assistant for Oil to Harold L. Ickes, the Oil Administrator and United States Secretary of the Interior, resigning in 1934.[45][46][47] He authored What are the Essentials of Sound Oil Conservation Legislation for Illinois?, which was published in 1939, and presented on "Illinois Oil and Gas Legislation" to the Illinois State Bar Association and the Indiana State Bar Association the same year.[48][49] Horween Leather CompanyHe and his brother inherited the family leather tannery business, Horween Leather Company in Chicago which had been founded in 1905. Among other things, the company provided the leather used in NFL footballs for many years. He was the company's chief manufacturing executive, and was working at the company in 1950.[15][32][40][44] [50] Horween ProfessorshipHe endowed the Horween Professorship at the University of Virginia, a research chair in the field of small manufacturing enterprises, in honor of his father and in memory of his wife, Genevieve Brown Horween.[51][52] CentenarianIn 1994, the NFL honored 95-year-old Arda Bowser as the league's oldest living ex-NFL player.[53] It was only later that NFL officials discovered that they had made a mistake – because Horween, who was 99 years old at the time, was still alive.[53] In 1996, Horween turned 100, becoming the first NFL player to turn 100.[18][19] He died in Charlottesville, Virginia, on May 26, 1997.[18] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||