|

Retour des cendres

The retour des cendres (literally "return of the ashes", though "ashes" is used here as a metaphor for his mortal remains, as he was not cremated) was the return of the mortal remains of Napoleon I of France from the island of Saint Helena to France and the burial in Hôtel des Invalides in Paris in 1840, on the initiative of Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers and King Louis Philippe I.[1] Background After his defeat in the War of the Sixth Coalition in 1814, Napoleon abdicated as Emperor of the French, and was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba. The following year he returned to France and took up the throne once more, beginning the Hundred Days. The Coalition powers which had prevailed against him the previous year mobilised against him, and defeated the French in the Battle of Waterloo. Napoleon returned to Paris and abdicated on 22 June 1815. Foiled in his attempt to sail to the United States, he gave himself up to the British, who exiled him to the remote island of St Helena in the South Atlantic. He died and was buried there in 1821. Previous attemptsIn a codicil to his will, written in exile at Longwood House on St Helena on 16 April 1821, Napoleon had expressed a wish to be buried "on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people [whom I] loved so much". On the emperor's death, General Henri Bertrand unsuccessfully petitioned the British government to let Napoleon's wish be granted. He then petitioned the ministers of the newly restored King Louis XVIII of France, from whom he did not receive an absolute refusal. Instead, the explanation given was that the arrival of the remains in France would undoubtedly be the cause or pretext for political unrest that the government would be wise to prevent or avoid, but that his request would be granted as soon as the situation had calmed and it was safe enough to do so. CoursePolitical discussionsEarly daysAfter the July Revolution, a petition demanding the remains' reburial in the base of the Colonne Vendôme (on the model of Trajan's ashes, buried in the base of his column in Rome) was refused by the Chamber of Deputies on 2 October 1830. However, ten years later, Adolphe Thiers, the new President of the Council (prime minister) under King Louis Philippe I and a historian of the French Consulate and First French Empire, dreamed of the return of the remains as a grand political coup de théâtre which would definitively achieve the rehabilitation of the Revolutionary and Imperial periods on which he was engaged in his Histoire de la Révolution française and Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire.[2][3] He also hoped to flatter the left's dreams of glory and restore the reputation of the July Monarchy (whose diplomatic relations with the rest of Europe were then under threat from its problems in Egypt, arising from its support for Muhammad Ali). It was, nonetheless, Louis Philippe's policy to try to regain "all the glories of France", to which he had dedicated the Château de Versailles, turning it into a museum of French history. Yet he was still reluctant and had to be convinced to support the project against his own doubts. Among the rest of the royal family, the Prince de Joinville did not want to be employed on a job suitable for a "carter" or an "undertaker"; Queen Maria Amalia adjudged that such an operation would be "fodder for hot-heads"; and their daughter Louise saw it as "pure theatre".[4] In early 1840, the government led by Thiers appointed a twelve-member committee (Commission des douze) to decide on the location and outline of the funerary monument and select its architect. The committee was chaired by politician Charles de Rémusat and included writers and artists such as Théophile Gautier, David d'Angers, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.[5] On 10 May 1840, François Guizot, then French ambassador in London, against his own will submitted an official request to the British government, which was immediately approved according to the promise made in 1822. For his part, the British Foreign Secretary (later Prime Minister) Lord Palmerston privately found the idea nonsensical and wrote about it to his brother, presenting it in the following terms: "Here's a really French idea".[4] 12 MayOn 12 May, during discussion of a bill on sugars, French Interior Minister Charles de Rémusat mounted the rostrum at the Chamber of Deputies and said:

The minister then introduced a bill to authorise "funding of 1 million [francs] for translation of the Emperor Napoleon's mortal remains to the Église des Invalides and for construction of his tomb". This announcement caused a sensation. A heated discussion began in the press, raising all sorts of objections as to the theory and to the practicalities. The town of Saint-Denis petitioned on 17 May that he instead be buried at their basilica, the traditional burial place of French kings. 25–26 MayOn 25 and 26 May, the bill was discussed in the Chamber. It was proposed by Bertrand Clauzel, an old soldier of the First French Empire who had been recalled by the July Monarchy and promoted to Marshal of France. In the name of the Commission des douze he endorsed the choice of Les Invalides as the burial site, not without discussing the other suggested solutions (besides Saint-Denis, the Arc de Triomphe, the Colonne Vendôme, the Panthéon de Paris, and even the Madeleine had been suggested to him). He proposed that the funding be raised to 2 million, that the ship bringing the remains back be escorted by a whole naval squadron and that Napoleon would be the last person to be buried in the Invalides. Speeches were made by republican critic of the Empire Glais-Bizoin, who stated that "Bonapartist ideas are one of the open wounds of our time; they represent that which is most disastrous for the emancipation of peoples, the most contrary to the independence of the human spirit." The proposal was defended by Odilon Barrot (the future president of Napoleon III's council in 1848), whilst the hottest opponent of it was Alphonse de Lamartine, who found the measure dangerous. Lamartine stated before the debate that "Napoleon's ashes are not yet extinguished, and we're breathing in their sparks".[7] Before the sitting, Thiers tried to dissuade Lamartine from intervening but received the reply "No, Napoleon's imitators must be discouraged." Thiers replied "Oh! But who could think to imitate him today?", only to receive Lamartine's reply that then spread right round Paris – "I do beg your pardon, I meant to say Napoleon's parodists."[7] During the debate Lamartine stated:

In conclusion, Lamartine invited France to show that "she [did not wish] to create out of this ash war, tyranny, legitimate monarchs, pretenders, or even imitators".[7] Hearing this peroration, which was implicitly directed against him, Thiers looked devastated on his bench. Even so, the Chamber was largely favourable and voted through the measures requested, although by 280 votes to 65 it did refuse to raise the funding from 1 to 2 million. The Napoleonic myth was already fully developed and only needed to be crowned. The July Monarchy's official poet Casimir Delavigne wrote:

4–6 JuneOn 4 or 6 June, Bertrand was received by Louis Philippe, who gave him the Emperor's arms, which were placed in the treasury. Bertrand stated on this occasion:

Louis Philippe replied, with studied formality:

This ceremony angered Joseph and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the latter writing in The Times:

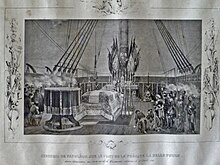

After the arms ceremony, Bertrand went to the Hôtel de Ville and offered to the president of the Municipal Council the council chair that Napoleon had left to the capital – it is now in the Musée Carnavalet. Arrival at Saint Helena At 7 pm on 7 July 1840, the frigate Belle Poule left Toulon, escorted by the corvette Favourite. The Prince of Joinville, the king's third son and a career naval officer, was in command of the frigate and the expedition as a whole. Also on board the frigate were Philippe de Rohan-Chabot, an attaché to the French ambassador to the United Kingdom and commissioned by Thiers (wishing to gain reflected glory from any possible part of the expedition) to superintend the exhumation operations; generals Bertrand and Gaspard Gourgaud; Count Emmanuel de Las Cases (député for Finistère and son of Emmanuel de Las Cases, the author of Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène); and five people who had been domestic servants to Napoleon on Saint Helena (Saint-Denis – better known by the name Ali Le Mameluck – Noverraz, Pierron, Archambault, and Coursot). Captain Guyet was in command of the corvette, which transported Louis Marchand, Napoleon's chief valet de chambre, who had been with him on Saint Helena. Others on the expedition included Abbé Félix Coquereau (fleet almoner); Charner (Joinville's lieutenant and second in command), Hernoux (Joinville's aide-de-camp), Lieutenant Touchard (Joinville's orderly), Bertrand's young son Arthur, and ship's doctor Rémy Guillard. Once the bill had been passed, the frigate was adapted to receive Napoleon's coffin: a candlelit chapel was built in the steerage, draped in black velvet embroidered with the Napoleonic symbol of silver bees, with a catafalque at the centre guarded by four gilded wooden eagles. The voyage lasted 93 days and, due to the youth of some of its crews, turned into a tourist trip, with the Prince dropping anchor at Cádiz for four days, Madeira for two days, and Tenerife for four days, while 15 days of balls and festivities were held at Bahia, Brazil. The two ships finally reached Saint Helena on 8 October and in the roadstead found the French brig Oreste, commanded by Doret, who had been one of the ensigns who had come up with a daring plan at île-d'Aix to get Napoleon away on a lugger after Waterloo and who would later become a capitaine de corvette. Doret had arrived at Saint Helena to pay his last respects to Napoleon but he also brought worrying news – the Egyptian incident, combined with Thiers' aggressive policy, were very close to causing a diplomatic rupture between France and the UK. Joinville knew that the ceremony would be respected but began to fear he would be intercepted by British ships on the return trip. The mission disembarked the following day and went to Plantation House, where the island's governor, Major General George Middlemore was waiting for them. After a long interview with Joinville (with the rest of the mission waiting impatiently in the lounge), Middlemore appeared before the rest of the mission and announced "Gentlemen, the Emperor's mortal remains will be handed over to you on Thursday 15 October". The mission then set off for Longwood, via the Valley of the Tomb (or Geranium Valley).[13] Napoleon's tomb was in a solitary spot, covered by three slabs placed level with the soil. This very simple monument was surrounded by an iron grille, solidly fixed on a base and shaded by a weeping willow, with another such tree lying dead by its side. All this was surrounded by a wooden fence and very close by was a spring whose fresh and clear water Napoleon had enjoyed. At the gate to the enclosure, Joinville dismounted, bared his head, and approached the iron grille, followed by the rest of the mission. In a deep silence they contemplated the severe and bare tomb. After half an hour Joinville remounted and the expedition continued on its way. Lady Torbet, owner of the land where the tomb was sited, had set up a booth to sell refreshments for the few pilgrims to the tomb and was unhappy about the exhumation since it would eliminate her already small profits from it. They then went in pilgrimage to Longwood, which was in a very ruinous state – the furniture had disappeared, many walls were covered with graffiti, Napoleon's bedroom had become a stable where a farmer pastured his beasts and got a little extra income by guiding visitors around it. The sailors from Oreste grabbed the billiard table, which had been spared by the goats and sheep, and carried off the tapestry and anything else they could carry, all the while being shouted at by the farmer with demands for compensation. Exhumation The party returned to the Valley of the Tomb at midnight on 14 October, though Joinville remained on board ship since all the operations up until the coffin's arrival at the embarkation point would be carried out by British soldiers rather than French sailors, and so he felt he could not be present at work that he could not direct. The French section of the party was led by the Count of Rohan-Chabot and included generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, Emmanuel de Las Cases, the Emperor's old servants, Abbé Coquereau, two choirboys, captains Guyet, Charner, and Doret, Dr. Guillard (chief surgeon of the Belle-Poule), and a lead-worker, Monsieur Leroux. The British section was made up of William Wilde, Colonel Hodson and Mr Scale (members of the island's colonial council), Mr. Thomas, Mr. Brooke, Colonel Trelawney (the island's artillery commander), Lieutenant Littlehales, Captain Alexander (representing Middlemore, who was indisposed, although he eventually arrived accompanied by his son and an aide), and Mr. Darling (interior decorator at Longwood during Napoleon's captivity).[14] By the light of torches, the British soldiers set to work. They removed the grille, then the stones that formed a border to the tomb. The topsoil had already been removed and the French shared among themselves the flowers that had been growing in it. The soldiers then pulled up the three slabs that were closing the pit over. Long efforts were needed to break through the masonry enclosing the coffin. At 9:30 the last slab was raised and the coffin could be seen. Coquereau took some water from the nearby spring, blessed it and sprinkled it over the coffin, before reciting the psalm De profundis. The coffin was raised and transported into a large blue and white striped tent that had been put up the previous day. Then they proceeded to open the bier, in complete silence. The first coffin, of mahogany, had to be sawn off at both ends to get out the second coffin, made of lead. Middlemore and Touchard then arrived and presented themselves, before the party proceeded to unsolder the lead coffin. The coffin inside this, again of mahogany, was remarkably well-preserved. Its screws were removed with difficulty. It was then possible to open, with infinite care, the final coffin, made of tin.[14]  When the lid was lifted what appeared was described by a witness as "a white form – of uncertain shape", which was the only thing visible at first at the light of the torches, briefly sparking fears that the body had decomposed extensively; however, it was discovered that the white satin padding from the coffin lid had detached and fallen over Napoleon's body, covering it like a shroud. Guillard slowly rolled the satin back, from the feet up: The body lay comfortably in a natural position with the head resting over a cushion while its left forearm and hand lay over his left thigh; Napoleon's face was immediately recognisable and only the sides of the nose seemed to have slightly contracted but overall, the face seemed, on the opinion of the witnesses, peaceful, and his eyes were fully closed, the eyelids even retaining most of the eyelashes; at the same time, the mouth was slightly open, showing three white incisors. As the body became dehydrated, its hairs started to protrude more and more from the skin, making it look as if the hairs had grown; this being a common phenomenon in well-preserved bodies. In Napoleon's case, this phenomenon was most prominently displayed in what would have been his beard and his chin was stippled with the beginnings of a bluish beard. The hands for their part were very white and the fingers were thin and long; the fingernails were still intact and attached to the fingers and they seemed to have grown longer, also protruding because of the dryness of the skin.[15][14] Napoleon wore his famous green uniform of the colonel of chasseurs which was perfectly preserved; his chest was still crossed by the red ribbon of the Legion of Honour, but all other decorations and medals over the uniform were slightly tarnished. His hat lay sideways across his thighs. The boots he wore had cracked at the seams, showing his four smaller toes in each foot.[15] All the spectators were in a state of visible shock: Gourgaud, Las Cases, Philippe de Rohan, Marchand, and all the servants wept; Bertrand barely fought his tears back. After two minutes' examination, Guillard proposed that he continue examining the body and open the jars containing the heart and the stomach, in part so that they could confirm or disprove the findings of the autopsy performed by the British when Napoleon died and which had found a perforated ulcer in his stomach. Gourgaud, however, suppressing his tears, became angry and ordered that the coffin be closed at once. The doctor complied and replaced the satin padding, spraying it with a little creosote as a preservative before putting back on the original tin lid (though without re-soldering it) and the original mahogany lid. The original lead coffin was then re-soldered.[15] The original lead coffin and its contents were then placed into a new lead coffin brought in from France[16] which, once soldered, was placed into the ebony coffin with combination lock that had been brought from France. This ebony coffin, made in Paris, was 2.56 m long, 1.05 m wide, and 0.7 m deep. Its design imitated classical Roman coffins. The lid bore the sole inscription "Napoléon" in gold letters. Each of the four sides was decorated with the letter N in gilded bronze and there were six strong bronze rings for handles. On the coffin were also inscribed the words "Napoléon Empereur mort à Sainte-Hélène le 05 Mai 1821" (Napoleon, Emperor, died at St Helena on 5 May 1821).[14] After the combination lock had been closed, the ebony coffin was placed in a new oak coffin, designed to protect that of ebony. Then this mass, totalling 1,200 kg, was hoisted by 43 gunners onto a solid hearse, draped in black with four plumes of black feathers at each corner and drawn with great difficulty by four horses caparisoned in black. The coffin was covered with a large (4.3 m by 2.8 m) black pall made of single piece of velvet sown with golden bees and bearing eagles surmounted by imperial crowns at its corners as well as a large silver cross. The ladies of Saint Helena offered to the French commissioner the tricolour flags that would be used in the ceremony and which they had made with their own hands, and the imperial flag that would be flown by Belle Poule.[17] Transfer to Belle Poule At 3:30, in driving rain, with the citadel and Belle Poule firing alternate gun salutes, the cortège slowly moved along under the command of Middlemore. Bertrand, Gourgaud, Las Cases the younger, and Marchand walked holding the corners of the pall. A detachment of militia brought up the rear, followed by a crowd of people, while the forts fired their cannon on every minute. Reaching Jamestown, the procession marched between two ranks of garrison soldiers with arms reversed. The French ships lowered their launches, with that of Belle Poule, ornamented with gilded eagles, carrying Joinville. At 5:30, the funeral procession stopped at the end of the jetty. Middlemore, old and ill, walked painfully over to Joinville. Their brief conversation, more or less in French, marked the point at which the remains were officially handed over to France. With infinite caution, the heavy coffin was placed in the launch. The French ships (up until then showing signs of mourning) hoisted their colours and all the ships present fired their guns. On Belle Poule 60 men were paraded, drums beat a salute, and funeral airs were played. The coffin was hoisted onto the deck and its oak envelope was taken off. Coquereau gave absolution and Napoleon had returned to French territory. At 6:30 the coffin was placed in a candlelit chapel, ornamented with military trophies, on the stern of the ship. At 10 the following day, mass was said on deck, then the coffin was lowered into the candlelit chapel in the steerage, while the frigate's band played.[18] Once this had been done, each officer received a commemorative medal.[19] The sailors divided up among themselves the oak coffin and the dead willow that had been taken away from the Valley of the Tomb. Return from Saint Helena At 8 am on Sunday, 18 October, Belle Poule, Favourite, and Oreste set sail. Oreste rejoined the Levant division, whilst the two other ships sailed towards France at full speed, fearful of being attacked. No notable setback occurred to Belle Poule and Favourite during the first 13 days of this voyage, though on 31 October they met the merchantman Hambourg, whose captain gave Joinville news of Europe, confirming the news he had received from Doret. The threat of war was confirmed by the Dutch ship Egmont, en route for Batavia. Joinville was sufficiently worried to summon the officers of both his ships to a council of war, to plan precautions to keep the remains out of harm's way should they meet British warships. He had Belle Poule prepared for possible battle. So that all the ship's guns could be mounted, the temporary cabins set up to house the commission to Saint Helena were demolished and the dividers between them, as well as their furniture, were thrown into the sea – earning the area the nickname "Lacédémone".[20] The crew were frequently drilled and called to action stations. Most importantly, he ordered Favourite to sail away immediately and make for the nearest French port. Joinville was aware that no British warship would attack the ship carrying the body, but also that they would be unlikely to extend the same generosity to Favourite. He doubted, with good reason, that he would be able to save the corvette if she got within range of an enemy ship, without risking his frigate and its precious cargo. Another hypothesis is that Favourite was the slower ship and would only have held Belle Poule back if they had been attacked. On 27 November Belle-Poule was only 100 leagues from the coasts of France, without having encountered any British patrol. Nonetheless, her commander and crew continued with their precautions – even though these were now unnecessary, because Anglo-French tensions had ceased, after France had had to abandon Egypt and Thiers been forced to resign. Arrival in FranceIn the meantime, in October 1840, a new ministry nominally presided over by Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult, but in reality headed by François Guizot, succeeded Thiers's cabinet in an attempt to resolve the crisis Thiers had provoked with the UK over the Middle East. This new arrangement gave rise to fresh hostile comment in the press as to the "retour des cendres":

Fearful of being overthrown thanks to the "retour" initiative (the future Napoleon III had just attempted a coup d'État) yet unable to abandon it, the government decided to rush it to a conclusion – as Victor Hugo commented, "It was pressed into finishing it."[22] Interior minister Tanneguy Duchâtel affirmed that "Whether the preparations are ready or not, the funeral ceremony will take place on 15 December, whatever weather should happen or arise."[23]  Everyone in Paris and its suburbs was conscripted to get the preparations done as quickly as possible, with the coffin's return voyage being faster than expected and internal political problems having caused considerable delays. From the Pont de Neuilly to Les Invalides, papier-mâché structures were set up which would line the funeral procession, though these were slapped together only late on the night before the ceremony. The funeral carriage itself, resplendently gilded and richly draped, was 10 m high, 5.8 m wide, 13 m long, weighed 13 tonnes, and was drawn by four groups of four richly caparisoned horses. It had four massive gilded wheels, on whose axles rested a thick tabular base. This supported a second base, rounded at the front and forming a semi-circular platform on which were set a group of genii supporting Charlemagne's crown. At the back of this rose a dais, like an ordinary pedestal, on which stood a smaller pedestal in the shape of a quadrangle. Finally 14 statues, larger than life and gilded all over, held up a vast shield on their heads, above which was placed a model of Napoleon's coffin; this whole ensemble was veiled in a long purple crêpe, sown with gold bees. The back of the car was made up of a trophy of flags, palms, and laurels, with the names of Napoleon's main victories. To avoid any revolutionary outbreak, the government (which had already insisted on the remains being buried with full military honours in Les Invalides) ordered that the ceremony would be strictly military, dismissing the civil cortège and thus infuriating the law and medical students who were to have formed it. Eventually, the students protested in Le National: "Children of the new generations, [the law and medical students] do not understand the exclusive cult that gives in to force of arms, in the absence of the civil institutions that are the foundation of liberty. [The students] do not prostrate themselves before the spirit of invasion and conquest, but, at the moment when our nationality seems to be demeaned, the schools had wished to pay homage by their presence to the man who was from the outset the energetic and glorious representative of this nationality."[24] The diplomatic corps gathered at the British embassy in Paris and decided to abstain from participating in the ceremony due to their antipathy to Napoleon as well as to Louis Philippe.[1] On 30 November, Belle-Poule entered the roadstead of Cherbourg, and six days later the remains were transferred to the steamer la Normandie. Reaching Le Havre, and then on to Val-de-la-Haye, near Rouen, where the coffin was transferred to la Dorade 3 for carrying further up the Seine, on whose banks people had gathered to pay homage to Napoleon. On 14 December, la Dorade 3 moored at Courbevoie in the northwest of Paris. Reburial The date for the reburial was set for 15 December. Victor Hugo evoked this day in his Les Rayons et les Ombres:

Even as far as London, poems commemorating the event were published; one read in part:

Despite the temperature never rising above 10 degrees Celsius, the crowd of spectators stretching from the Pont de Neuilly to the Invalides was massive. Some houses' rooftops were covered with people. Respect and curiosity won out over irritation, and the biting cold cooled all restlessness in the crowd. Under pale sunlight after snow, the plaster statues and gilded-card ornaments produced an ambiguous effect upon Hugo: "the niggardly clothing the grandiose".[27] Hugo also wrote:

The cortège arrived at the Invalides around 1:30, and at 2 pm it reached the gate of honour. The king and all France's leading statesmen were waiting in the royal chapel, the Église du Dôme. Joinville was to make a short speech, but nobody had remembered to forewarn him – he contented himself with a sabre salute and the king mumbled a few unintelligible words.[29] Le Moniteur described the scene as best it could:

General Louis Marie Baptiste Atthalin stepped forward, bearing on a cushion the sword that Napoleon had worn at the battles of Austerlitz and Marengo, which he presented to Louis Philippe. The king then turned to Bertrand and said: "General, I charge you with placing the Emperor's glorious sword upon his coffin." Overcome with emotion, Bertrand was unable to complete this task, and Gourgaud rushed over and seized the weapon. The king turned to Gourgaud and said: "General Gourgaud, place the Emperor's sword upon the coffin."[31] In the course of the funeral ceremony, the Paris Opera's finest singers were conducted by François Habeneck in a performance of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Requiem. The ceremony was more worldly than reverent – the deputies were particularly uncomfortable:

The bearing of Marshal Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey, the governor of the Invalides, somewhat redeemed the impertinence of the court and the politicians. For a fortnight he had been in agony, pressing his doctor to keep him alive at least to complete his role in the ceremony. At the end of the religious ceremony he managed to walk to the catafalque, sprinkled holy water on it and pronounced as the closing words: "And now, let us go home to die".[33] From 16 to 24 December, the Église des Invalides, illuminated as on the day of the ceremony, remained open to the public. The people had long disbelieved in Napoleon's death and a rumour spread that the tomb was only a cenotaph. It was claimed that on Saint Helena the commission had found only an empty coffin and that the British had secretly sent the body to London for an autopsy;[34] and yet another rumour was that in 1870 the Emperor's mortal remains had been removed from the Invalides to save them from being captured in the Franco-Prussian War and had never been returned.[35] Hugo wrote that, though the actual body was there, the people's good sense was not amiss:

Political failureThe return of the remains had been intended to boost the image of the July Monarchy and to provide a tinge of glory to its organisers, Adolphe Thiers and Louis Philippe. Thiers had spotted the rise of the French infatuation with the Empire that would go on to become the Napoleonic myth. He also thought that returning the remains would seal the new spirit of accord between France and the United Kingdom even though the Egyptian affair was beginning to agitate Europe.[36] As for Louis Philippe he would be disappointed in his hope to use the remains' return to give additional legitimacy to his monarchy, which was rickety and indifferent to the French people.[1] The great majority of the French, excited by the return of the remains of one whom they had come to see as a martyr, felt betrayed that they had been unable to render him the homage that they had wished. Hence, the government began to fear rioting and took every possible measure to prevent the people from assembling. Accordingly, the cortège had been mostly riverborne and had spent little time in towns outside Paris. In Paris, only important personages were present at the ceremony. Worse, the lack of respect shown by most of the politicians shocked public opinion and revealed a rift between the people and their government.[36] The "retour" also did not prevent France from losing its diplomatic war with the United Kingdom. France was forced to give up supporting its Egyptian ally. Thiers, losing his way in aggressive policies, was ridiculed, and the king was compelled to dismiss him even before Belle Poule arrived. Thiers had managed to push through the return of the remains but was unable to profit from that success. MonumentIn April 1840 the Commission des douze organised a competition in which 81 architects participated, whose projects were exhibited in the recently completed Palais des Beaux-Arts. After a protracted process, Louis Visconti was selected as project architect in 1842 and finalised his design around mid-1843.[5] Visconti created a circular hollow beneath the dome, as a kind of open crypt. At its center is a massive sarcophagus which has often been described as made of red porphyry, including in the Encyclopædia Britannica as of mid-2021,[37] but is actually a purple Shoksha quartzite from a geological region near Lake Onega in Russian Karelia. These quarries were located in the Karelian region of Finland which then belonged to the Russian Empire and were under the suzerainty of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia;[38] the French ended up paying around 200,000 francs for the stones, borne by the French government.[39] The sarcophagus rests upon a base of green granite from the Vosges, which rests in turn upon a slab of black marble, 5.5m x 1.2m x 0.65m, quarried at Sainte-Luce and transported to Paris with great difficulty.[40] The monument took years to complete, not least because of the exceptional requirements for the stone to be used. The Shoksha quartzite, intended as an echo of the porphyry used for late Roman imperial burials, was quarried in 1848 upon Nicholas I's special permission by Italian engineer Giovanni Bujatti, and shipped via Kronstadt and Le Havre to Paris, where it arrived on 10 January 1849. The sarcophagus was then sculpted by marbler A. Seguin using innovative steam-machinery techniques. It was almost finished by December 1853, but the final stages were delayed by the sudden death of Visconti that month and by Napoleon III's alternative project to move his uncle's resting place to the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which he renounced after having commissioned plans for it from Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.[5][17] On 2 April 1861, Napoleon's coffin was transferred from the chapel of Saint-Jérôme, where it had lain since 1840. The transfer was accompanied only by an intimate ceremony: present were Napoleon III, Empress Eugénie, Napoléon Eugène, Prince Imperial, other related princes, government ministers, and senior officials of the crown.[36] Sources

Bibliography

Notes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Retour des Cendres.

|