|

Rhön Mountains

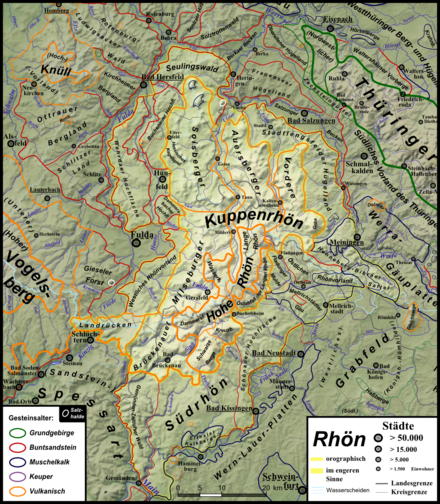

The Rhön Mountains (German: [ˈʁøːn] ⓘ) are a group of low mountains (or Mittelgebirge) in central Germany, located around the border area where the states of Hesse, Bavaria and Thuringia come together. These mountains, which are at the extreme southeast end of the East Hesse Highlands (Osthessisches Bergland), are partly a result of ancient volcanic activity. They are separated from the Vogelsberg Mountains by the river Fulda and its valley. The highest mountain in the Rhön is the Wasserkuppe (950.2 metres or 3,117 feet), which is in Hesse. The Rhön Mountains are a popular tourist destination and walking area. OriginsThe name Rhön is often thought to derive from the Celtic word raino (=hilly), but numerous other interpretations are also possible. Records of the monks at Fulda Abbey from the Middle Ages describe the area around Fulda as well as more distant parts of the Rhön as Buchonia, the land of ancient beech woods. In the Middle Ages beech was an important raw material. Large scale wood clearing resulted in the "land of open spaces" (Land der offenen Fernen), 30% of which, today, is forested. GeographyLocationLying within the states of Hesse, Bavaria and Thuringia, the Rhön is bounded by the Knüll to the northwest, the Thuringian Forest to the northeast, the Grabfeld to the southeast, Lower Franconia to the south, the Spessart forest to the southwest and the Vogelsberg mountains to the west. Division by type of volcanic activityBased on the effects of ancient volcanic activity, the Rhön can be divided into the "Anterior Rhön" (Vorderrhön), the "Kuppen Rhön" (geographical region 353, Kuppenrhön) and the "High Rhön" (354, Hohe Rhön). The terms "Anterior Rhön" (Vorderrhön) and "Kuppen Rhön" (Kuppenrhön or Kuppige Rhön) are somewhat misleading, since the "Anterior Rhön" also consists mainly of Kuppen or low mountains with dome-shaped summits. The name has genuine historic origins: the "Anterior Rhön", as viewed from Thuringia, forms the foothills (or anterior part) of the mountain region. In this gently rolling landscape numerous individual dome-shaped mountains rise on both sides of the border of Hesse and Thuringia and also, in some places, in Bavaria. These Kuppen are the remnants of ancient volcanos or volcanic activity. Natural regionsNatural region divisionsThe Rhön and its immediate declivities are divided by the Handbook of the Natural Region Divisions of Germany into the following natural regions:[1]

High Rhön   The High Rhön (German: Hohe Rhön or Hochrhön) is that part of the central Rhön that lies in Hesse, Bavaria, and to a lesser extent in Thuringia; it covers an area of 344 km2 (132.8 sq mi)[3] Landscape fact files by the BfN (c.f. section on Natural region division) and is up to 950.0 m (3,117 ft) and whose highland plateaux with elevations starting at 600 to 700 m (1,969 to 2,297 ft) are covered by solid basalt. Its core area in the northeast used to be called the Plattenrhön. The High Rhön is a natural regional major unit in the East Hesse Highlands; see Natural regions. The High Rhön has five main mountainous regions:

At the heart of the Rhön, albeit only the fourth highest summit of these mountains, is the Heidelstein (925.7 m (3,037 ft)) on the border between Bavaria and Hesse on the Rhine-Weser watershed. It forms the main high point on the plateau of the Long Rhön, which runs northeast over the Stirnberg (901.9 m (2,959 ft)) as far as the Ellenbogen (Schnitzersberg) (815.5 m (2,676 ft)) without crossing any significant lower ground. Within the Long Rhön the basalt layer is almost unbroken. At the Heidelstein, another natural region, the Wasserkuppen Rhön, branches off in a north to northwesterly direction to the Rhön's highest summit, the Wasserkuppe (950.0 m (3,117 ft)), whose basalt likewise covers a wide area, but is broken in places by bunter sandstone and muschelkalk – in particular the basalt kuppen of the Weiherberg (785.7 m (2,578 ft), northwest) and Ehrenberg (816.5 m (2,679 ft) northeast) are slightly separated from the rest. Between the northeastern end of the Wasserkuppen Rhön at the Ehrenberg and the plateau of the Long Rhön from the Heidelstein to just beyond the Stirnberg is the Upper Ulster valley, which cuts into the bunter sandstone by up to about 300 m (984 ft) and divides the Plattenrhön in two. The Long Rhön runs southwest along the main watershed to the Dammersfeld ridge which continues along the watershed via the Hohe Hölle (893.8 m (2,932 ft)) and Eierhauckberg (909.9 m (2,985 ft)) to the Dammersfeldkuppe (927.9 m (3,044 ft)), the ridge being clearly narrower than the Long Rhön and its basalt layer being interrupted several times. The Großer (808.6 m (2,653 ft)) and Kleiner Auersberg (about 808 m (2,651 ft)), separated by the valley of the Schmale Sinn, are also part of this natural region. South of Heidelstein and Hoher Hölle the narrow head of the Brend valley near Bischofsheim forms the boundary with another mountain group of the High Rhön, the Kreuzberg Group, which contains the Arnsberg (843.1 m (2,766 ft)) and the Kreuzberg (927.8 m (3,044 ft)). In between these two mountains lies the source of the Sinn. This river, which forms a wide and deep valley head flanked by the Dammersfeld ridge, flows to the southwest. On the other side of the Sinn valley, and southwest of the Kreuzberg Group, are the Black Mountains (German: Schwarze Berge), which include the Schwarzenberg (Feuerberg, 832.0 m (2,730 ft)) and Totnansberg (839.4 m (2,754 ft)). They are separated from the Kreuzberg Group by the narrow valley of the Premich's upper reaches, the Kellersbach. Clearly different from the aforementioned ridges is the eastern slope of the Long Rhön, which forms the transition zone from the High Rhön to the muschelkalk region of the Mellrichstadt Gäu (Mellrichstädter Gäu), the eastern part of the Werra Gäu Plateaux. Individual domes rise from the descending Triassic beds east of the solid basalt covering of the Long Rhön in the interfluvials of the tributaries of the Franconian Saale between Brend and Streu, notably the Gangolfsberg (735.8 m (2,414 ft)) and the Rother Kuppe (710.6 m (2,331 ft)). This landscape bears a clear resemblance to the Kuppen Rhön. The Wildflecken Training Area, which covers an area of 74 km2 (28.6 sq mi), equivalent to almost a quarter of the High Rhön, is not accessible to the public. Kuppen Rhön   The 1,200 square kilometres (460 sq mi)[3] of the "Kuppen Rhön in its narrow sense", to which the Anterior Rhön also belongs,[4] is the wide outer fringe of markedly different relief, that circles around the High Rhön from the northeast (in Thuringia) through the northwest (in Hesse) to the southwest (with small parts in Bavaria). Numerous dome-shaped isolated mountains and hills rise above the valleys to 500–800 metres (1,640–2,625 ft), whose basalt covering is concentrated around the summit regions and does not blanket the entire landscape, as it does in the High Rhön. The domes or kuppen are the stumps of heavily weathered former volcanoes or volcanic pipes. Between pointed cones and broad domes lie many small plateaux, especially common in the Anterior Rhön. Over a foundation of Middle Bunter sandstone lie stratigraphic sequences of Upper Bunter (Röt), muschelkalk and keuper, the last two rocks only surviving where they have been protected by an overlying sheet of basalt. Woods cover less than a third of the area and are largely restricted to the summit regions. Five natural regions may be distinguished:

The eastern part of the Kuppen Rhön is the Thuringian Anterior Rhön, which reaches a height of 750.7 m (2,463 ft) at the huge plateau of the Gebaberg in the southeast. There is hardly any keuper escarpment there at all. The kuppen and plateaux rest directly on a bedrock of muschelkalk. This natural region runs northeast from the wide, pyramidal Pleß, 645.4 m (2,117 ft), far into the Bunter sandstone of the Stadlengsfeld Hills that descend to the River Werra. In the west the Middle Felda Valley forms a natural boundary between Kaltensundheim in the south and below Dermbach in the north. West of the Felda valley is the Auersberg Kuppenrhön (Auersberger Kuppenrhön), which lies mainly in Thuringia, but extends into Hesse in the southwest. This natural region runs from the town of Auersberg in the south, which gives the region its name, to the boundary with the Long Rhön at the Ellenbogen, 756.8 m (2,483 ft). In the northeast of the region, the prominent kuppe of the Baier reaches a height of 713.9 m (2,342 ft), but its northernmost summit is the popular viewing mountain of Oechsen. The western boundary is the Middle Ulster Valley between Hilders in the south and below Buttlar in the north. West of the Ulster valley is the Soisberg Kuppenrhön (Soisberger Kuppenrhön), which lies mainly in Hesse, with elements in the southeast also extending into Thuringia. This region reaches a height of 629.9 m (2,067 ft) at the Soisberg in the north where the countryside is enclosed by the Seulingswald forest. It reaches even greater elevations in the extreme southeast, where the Habelberg (718.5 m (2,357 ft)) west of Tann stands opposite to and north of the Auersberg. This natural region is well known for the Hessian Skittles, a striking regular array of high, gently rounded, basalt cones up to 552.9 m (1,814 ft). North and south of the skittles most of the kuppen in this natural region are also arranged in a row along the watershed between the Werra and the Fulda and between the Ulster and the Haune respectively. To the west they do not quite reach the Haune at the Haune Plateaux; to the south the Nüst valley below Obernüst forms a natural boundary. The almost entirely Hessian range of the Milseburg Kuppenrhön (Milseburger Kuppenrhön), which bounds the Wasserkuppen Rhön, up to 950.0 m (3,117 ft), south of the Nüst valley and west of the Ulster valley. Again the keuper escarpment is missing and even the muschelkalk only appears in islands around individual domes. The majority of the basalt and phonolite cones sit directly on the sandstones of the Middle Bunter. Cutting deeply into the sandstone, the rivers of the Haune and the Fulda flow westwards. The phonolitic cone of the Milseburg (835.2 m (2,740 ft)) is the only mountain in the Kuppen Rhön that exceeds the 800-metre-mark. Even the height of the Großer Nallenberg (768.3 m (2,521 ft)) south of the Fulda, is not reached in other parts of the region. To the southwest the area is bounded by the rocky sandstone of the Hoher Kammer (700.0 m (2,297 ft)), as it descends from the heights of the Dammersfeld ridge (up to 927.9 m (3,044 ft)).  Separated from the Kammer by the upper reaches of the Döllbach, the Döllau, the Große Haube (658.1 m (2,159 ft)) on the Rhine-Weser watershed opens the Brückenau Kuppenrhön, whose western half is in Hesse and whose eastern half is in Bavaria. The valleys of the Schmaler and Breiter Sinn running southwestwards, divide the natural region, which is clearly more heterogenous than the other ranges of the Kuppen Rhön, into three segments. In the west, the rugged plateaux of dolerite and basalt transition into the Landrücken, whilst the northeast of the Kleiner Auersberg (c. 808 m (2,651 ft)) leads up to the Dammersfeld ridge. Between the more rugged plateaux and ridges there are gently domed basalt intrusions that rise up, especially in the southeast, left of the Sinn near Bad Brückenau. The Dreistelzberg in the extreme south reaches 660.4 m (2,167 ft). Peaks The most well-known peaks in the Rhön Mountains include:

RiversThe following rivers rise in the Rhön Mountains or flow by or through them (length given in brackets):

History The name Rhön is believed to be of Celtic origin. A regional Celtic presence is well established, with an important Celtic town at Milseburg. Furthermore, there are circular embankments that could be both of Celtic and of Germanic origin in the Kuppenrhön on the Stallberg and the Kleinberg mountains. Many names of places, mountains and meadows in the Rhön likely have their origins in Celtic root words. Up to the 10th century parts of the Rhön belonged to Altgau Buchonia. This term was coined by the Romans in Late Antiquity and described an ancient beech forest in the Rhön and the neighbouring low mountain ranges of the Spessart and Vogelsberg. Expansive stands of beech still exist today in the area. Due to the far reaching view from the Rhön mountains, they became sites for hilltop castles in the Middle Ages. One example is Hauneck Castle (Burg Hauneck) on the Stoppelsberg, the ruins of which can still be seen. It served to oversee and protect traffic on the ancient road, the Antsanvia, as well as protecting the villages in the Haune valley. In the Middle Ages the Würzburg Defences (landwehr) were erected on the Hochrhön for the protection of its farmers. The Rhön was also home to the Christian Community known as the Bruderhof from 1926 to 1937 when it was dissolved by Nazi persecution.[5] Biosphere ReserveIn 1991 UNESCO declared parts of the Rhön a Biosphere Reserve on account of its unique high-altitude ecosystem. Flora and faunaAs a result of its geography and geology the Rhön is an area with higher-than-average number of different habitats and species. But man, too, has generated valuable secondary habitats by creating a rich cultural landscape. Plant life  Compared with other low mountain regions, the Rhön is particularly rich in plant varieties. Its natural vegetation would probably be dominated by beech woods with scattered groups of other trees, but today beech trees are very much in decline. A few of these ancient woods were identified as core elements of the Rhön biosphere reserve. The higher beech woods are a habitat for rare, sometimes isolated, species of plant such as the Alpine blue-sow-thistle, giant bellflower and annual honesty. The vegetation of the lower-lying beech woods has a mix of mountain and other varieties. In addition to common wildflowers like the martagon lily, lily of the valley, wild chervil and wild garlic, various orchids also flourish here including Cephalanthera orchids, the yellow coralroot, bird's-nest orchid, lady's slipper and lady orchid. Only small areas of the Rhön landscape are essentially open: the raised bogs (Hochmoore), the rock outcrops and the stone runs. These habitats are home to highly specialised species. The raised bogs of the Long Rhön - the Red Moor (Rotes Moor) and the Black Moor (Schwarzes Moor) are floristically important links between the northern and Alpine raised bogs. Here, for example, can be found sundews, crowberry and cottongrass. Growing amongst the rocks of the volcanic mountains are rare species such as Cheddar pink, sweet william catchfly, oblong woodsia and fir clubmoss. There are no naturally occurring coniferous forests in the Rhön, but notable species of wild flower such as the lady's slipper orchid, creeping lady's tresses and burning-bush are found in the forests of mixed pine. The cultural landscape formed by humankind over the centuries also has a great variety of habitats and plants however, today, the extensive grassland areas are amongst the most threatened and heavily cultivated habitats. It is on the semi-arid grasslands and juniper heaths that the silver thistle, symbol of the Rhön region, grows, alongside gentians, pasque flowers and wood anemones, as well as orchids like the early purple, fragrant and fly orchids. Rarer flowers include the various bee orchids and the military, lady, burnt, green-winged, man, pyramidal, frog and lizard orchids. Along the southern fringes of the Rhön, on the so-called slopes of steppe heathland (Steppenheidenhängen) grow warmth-loving plants such as white rock-rose, erect clematis and honewort. Amongst the most valuable habitats in the Rhön are the mountain meadows and fields of mat grass (Nardetum strictae) on the higher slopes.[6] Characteristic plants here include the monkshood, northern wolfsbane, common moonwort, martagon lily, greater butterfly orchid, perennial cornflower and wig knapweed. Bog-bean, grass of Parnassus' western marsh orchid and lousewort are found in the wet meadows and low marshes; and the extremely rare large brown clover, hairy stonecrop and Pyrenean scurvygrass in the springwater marshes of the Hohe Rhön. WildlifeThe wildlife in the Rhön mountains is similar to that of other low mountain ranges, but there are also some unusual species. In addition to the more common mammals such as roe deer, fox, badger, hare and wild boar, there are also smaller mammals such as the dormouse, common water shrew and Miller's water shrew. One unusual regional species is the alpine shrew. Birds occurring here include the black grouse, the capercaillie, the black stork, the eagle owl, the corncrake, the red-backed shrike and the wryneck. There are also two species endemic to the Rhön: the rove beetle and a local snail, the Rhönquellschnecke (Bythinella compressa). Rhön umbrella brandThe Dachmarke Rhön project (Rhön umbrella brand project) is run by the Rhön working group and its aim is to promote a common identity for the Rhön region and to present a unified view of the area to the outside world and to harmonise the marketing measures of the three participating federal states. TourismThese mountains are a popular tourist destination. Hikers come for the nearly 6,000 km (3,700 mi) of trails, and gliding enthusiasts have been drawn to the area since the early 20th century. More recently, farm holidays have been flourishing in the region. Attractions

Villages and towns in the Rhön

Towns in the vicinity of the RhönTowns and larger villages close to the Rhön are: Walks and hiking trails There are well-marked walks and hiking trails in the Rhön which are looked after by the Rhön Club. The Rhön-Höhen-Weg ("Rhön Heights Walk" or RHW) is marked with a horizontal, red teardrop. It is 137 km (85 mi) long and runs from Burgsinn in Main-Spessart district through Roßbach, Dreistelz, Würzburger Haus on the Farnsberg, Kissinger Hütte on the Feuerberg, Kreuzberg (monastery), Oberweißenbrunn, through the Red and Black Moors, over the Ellenbogen and the Emberg via Oberalba, past Baier to Stadtlengsfeld and on to its destination at Bad Salzungen on the Werra River. Other hiking trails are:

In addition the following pass through the Rhön:

See alsoReferences

Sources

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||