|

Ryah Ludins

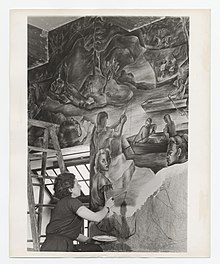

Ryah Ludins (1896–1957) was a Ukrainian-born American muralist, painter, printmaker, art teacher, and writer. She made murals for post offices and other government buildings during the Great Depression and also obtained commissions for murals from Mexican authorities and an industrial concern. Unusually versatile in her technique, she made murals in fresco, mixed media, and wood relief, as well as on canvas and dry plaster. She exhibited her paintings widely but became better known as a printmaker after prints such as "Cassis" (1928) and "Bombing" (about 1944) drew favorable notice from critics. She taught art in academic settings and privately, wrote and illustrated a children's book, and contributed an article to a radical left-wing art magazine. A career spanning more than three decades ended when she succumbed to a long illness in the late 1950s. Early life and educationBorn in Ukraine, Ludins came to New York City aged eight in 1904 and spent most of the rest of her life in the city. After graduating from high school she enrolled in Columbia Teachers College in 1920, intending to take up art education as her career.[1][2] While studying there, she received an honorable-mention award in an exhibition of textile design held at a Manhattan gallery devoted to the applied arts called the Art Alliance of America.[3][4] A year later, having earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Fine Arts and Fine Arts Education, she began studies at the Art Students League of New York where she took life classes from Kenneth Hayes Miller.[5][6] In 1925 she embarked on travels that took her first to Paris, where she studied with André Lhote, and then to Mexico City where she took classes at the National Polytechnic Institute of Mexico.[1] During World War II Ludins studied printmaking under William Hayter at his Atelier 17, then located in Manhattan.[5] Career in artLudins' career in art extended for more than three decades from 1922 to a time close to her death in 1957. During those years, she taught art both in academic settings and privately; she painted canvases and made prints that received warm critical reception; and became a well-known muralist, using both painting and relief methods. She exhibited in New York galleries, including the Morton, Milch, Downtown, and Willard, as well as the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, the National Academy of Design, and the Art Institute of Chicago. She held memberships in the New York Artists Equity Association and American Artists' Congress as well as the Mural Artists Guild and the National Society of Mural Painters.[1][7][8][9] In 1938, a newspaper columnist included her in a list of nine women said to have achieved outstanding success in the arts.[10] For much of her career, Ludins lived and worked in Manhattan's Chelsea Hotel during the colder months and spent her summers in a studio at her parents' home in Putnam Valley, New York.[1][11][12] Art instructorImmediately after graduating from Columbia Teachers College in 1922, Ludins took a position teaching elements and principles of design in the Department of Home Economics at the North Carolina College for Women, Greensboro.[13] After returning from her European travels in the mid-1920s, she began teaching in summer sessions of Columbia Teachers College in a sequence of appointments that ended with the session for 1938.[1][6][14] In 1932, she also served as an art instructor in the College of Education of Ohio University.[15] Later in her life, up to the time when a long illness brought the practice to an end, she gave private lessons to a few students at a time in her Chelsea Hotel studio apartment.[16][11] Painter and printmaker(1) Ryah Ludins, Untitled (Provincetown), 1925, drawing in pencil, 19 1/4 x 12 3/8 inches (2) Ryah Ludins, Cassis, 1928, lithograph, 16 x 11 1/2 inches (3) Ryah Ludins, Mexican Village, 1937, etching, 6 x 8 inches (3) Ryah Ludins, Bombing, about 1944, etching, 9 7/8 x 12 inches After turning from art instruction as her primary career, Ludins became a professional painter and printmaker. In 1928, she made a drawing of a street in Provincetown, Massachusetts, (shown above) which shows her ability at this early stage in her career as artist. A year later, she made a lithograph of Cassis, a town in southern France (shown above) which shows her skill as printmaker. In 1929, she showed oils in a group exhibition of forty artists at the Morton Galleries in Manhattan and a year later showed watercolors in a group exhibition at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh.[17][18] Beginning in 1930, she participated in group shows of prints. That year, she had a print called "Cassis" selected in an exhibition sponsored by the American Institute of Graphic Arts. Called "Fifty Prints of the Year", the show was the fifth in an irregular series that extended from 1925 into the late 1930s.[19] A well-known artist, John Sloan, was responsible for selecting prints. In addition to "Cassis", he selected works by Stuart Davis, Morris Kantor, Raphael Soyer, Max Weber, and others.[20][21] Early in 1931, she showed block prints in a group exhibition at the Philadelphia Print Club and later that year she showed lithographs in another group at the Art Institute of Chicago.[22][23] In 1937, on her return from extensive travels in Mexico, she made an etching called "Mexican Village" (shown above) which shows her ability in that medium. In 1945, another etching, this one called "Bombing" (shown above), attracted attention.[5][24][25] It was shown that year in the 30th annual exhibition by the Society of American Etchers held at the National Academy of Design and also at the Willard Gallery in Manhattan and then, in 1947, at the Leicester Galleries in London.[5] Muralist(1) Ryah Ludins, fresco, (detail, probably of "Modern Industry"), 1934, in the State Museum at Morelia, Mexico) (2) Ryah Ludins, Recreational Grounds of New York City, 1939, fresco in the men's recreation room of Bellevue Hospital, Manhattan, 632 square feet on one wall (3) Ryah Ludins, Cement Industry, 1938, mural in the post office at Nazareth, Pennsylvania (4) Ryah Ludins, Valley of the Seven Hills, 1943, painted wood relief mural 16 ft. 8 in. wide and 7 ft. 6 in. high, located in the post office at Cortland, New York

Robert Rightmire, Living New Deal (in database entry for “Post Office Mural – Nazareth PA”)[26]

Having had an interest in making murals from an early age, Ludins observed examples of the muralist movement in Mexico City during travels in the late 1920s. With a referral from Diego Rivera in hand, she returned to Mexico in 1933 to become an assistant to the Mexican-American muralist, Pablo O'Higgins.[27] 'Higgins taught her the fresco technique of mural making and helped her get her first mural commission. This was a work for the official newspaper of the political party that controlled Mexico from 1929 to 2000.[28] The commission led to others, including, in 1934, a fresco called "Modern Industry" for the State Museum at Morelia.[1][26][29] A photo of what is probably this fresco is shown above. In 1935 she returned to New York from Mexico began work in the Federal Arts Project, serving, at various times, as artist, senior artist, or supervisor.[30] Over the succeeding eight years, she designed seven murals of which four were completed.[26] One of these was a fresco called "Recreational Grounds of New York City" that she made for the men's recreation room of New York's Bellevue Hospital (1939).[1][5] A photo of this fresco is shown above. Other Federal Arts Project murals by her include "New York Harbor" (made in wood intarsia, location unknown).[31] In 1941 she was runner up in Federal Arts Project competitions for two projects in New York City and one in Washington, D.C.[26][32] As well as working for the Federal Arts Project, Ludins was employed by the Section of Fine Arts, then part of the U.S. Treasury Department and later a component of the Federal Works Agency.[9] As a member of the Section of Fine Arts, she completed two post office murals. The first, called "Cement Industry" is located in Nazareth, Pennsylvania (1938, oil on dry plaster, shown above).[33][34] The second, called "Valley of the Seven Hills" is located in Cortland, New York (1943, painted wood relief, also shown above).[35] Also in the late 1930s, Ludins joined with architects, landscape designers, mural painters, and sculptors in an informal collaborative to design buildings for the 1939 New York World's Fair.[36] Two years later, as the opening date of the World's Fair drew near, she joined other Federal Art Project muralists in preparing works for the Works Progress Administration community building. The group was led by Anton Refregier and, in addition to Ludins, it included Philip Guston, Eric Mose, and Seymour Fogel.[37][38] Ludins' mural was a wood relief called "Recreational Activities".[31] In 1937 Ludins exhibited with other Federal Art Project muralists in an exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art and three years later she showed at the Whitney Museum with other members of the National Society of Mural Painters.[36][39] In 1953, she made her last mural. Called "Steel", it was a commission from the J.B. Kendal Steel Company in Washington, D.C.1953 mural for a steel company.[40] Artistic style

Diana Klotts, "Speaking of Women", a syndicated column that appeared in the Jewish Herald-Voice of Houston, Texas, March 24, 1938.[41]

Ludins produced oil paintings on canvas, watercolors, lithographs, and etchings. She made murals via oil on canvas, oil on plaster, fresco, mixed media, and painted wooden relief.[1][33] She was not known for portraiture, but rather for village and harbor scenes, pictures showing groups of people at work and play, and industrial subjects. Her compositions were seen as "lively", displaying "unusually clean, clear technique", and abstract with "few concrete images".[18][23][24][42] She was considered to be a modernist with a delicate touch who was capable of showing "surging movement" in her work.[24][42] Author and illustratorIn 1928, Ludins prepared the cover design and made 120 pen and ink illustrations for three school readers in a set called Adventures in Reading by E. Ehrlich Smith and others (Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, Doran and Co.).[1][43][12] In 1931 Ludins wrote and illustrated a children's book entitled Wonder Rock (New York, Coward & McCann). An early review described it as "an old American Indian legend told and pictured in a beautiful and fascinating small book".[44] It tells a story of two lost children who receive help from animals, including a mouse, a raccoon, a grizzly bear, a mountain lion, and especially an ordinary earthworm in their struggle to find their way back home.[45]

Ryah Ludins, "A Child's Point of View", Art Front, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 17

Ludins wrote an article for the February 1937 issue of the radical magazine, Art Front. Reviewing an exhibition of paintings and graphic art made by children who participated in a Works Progress Agency art teaching project, she said the works on display should be taken seriously but, more importantly, the project demonstrated the importance of giving children "an opportunity to use their natural creative power to express their world of emotion". Art instruction in the schools should be seen as "a logical step in the creation and development of a living growing American culture of creators as well as appreciators".[46] At the time she wrote, Ludins was a member of the Art Front editorial board along with Jacob Kainen, Mitchell Siporin, Charmion Von Wiegand, and others.[46] Personal life and familyLudins was born on March 28, 1896, in Mariupol, a city in south-eastern Ukraine.[47] Her father was David George Ludschinski and her mother was Olga Richman Ludschinski. Her birth name was Ryah Ludschinski.[3] She had three younger siblings.[48][49] Ludins' father, David George Ludschinski, changed the family name to Ludins after bringing his family to the United States in 1904.[26] He was a builder and real estate speculator. He partnered with his brother, Leo Ludins, and a man named Louis Romm, to form the Ludins & Romm Realty Company in 1905.[50] David and Leo also did business as Ludins Brothers. Both firms worked mainly in northern Manhattan and the Bronx.[51][52] In the 1920s, the two brothers built apartment houses in the Bronx, one of them a structure of six stories with 185 rooms and 8 storefronts.[53] David Ludins was characterized as a "Russian Jewish intellectual" when the socialist Zionist, Nachman Syrkin, first encountered him and his family in 1913.[54] Judging by their participation in leftist organizations during the 1930s, Ludins and her two siblings all advocated radical causes.[46][55][56] Tima made headlines when she denounced an investigation by the United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security chaired by William E. Jenner in 1953.[57] She was a teacher in New York City public schools. Eugene was an artist. In 1934, Ludins married a Mexican named Juan de Fuentes, but the marriage lasted only a few months. One source reports that she told her niece, "she liked men, she just didn’t want to find one in her bed in the morning".[26] Following a long illness, Ludins died at her home in the Chelsea Hotel on August 30, 1957.[1] Other names usedDuring her life, Ludins was referred to as Ryah Ludschinski, Ryah Ludins, Ryah R. Ludins, and Ryah L. de Fuentes,[2][7] Her surname was sometimes misspelled Ludens.[42] References

|

||||||||||