|

Senescence

Senescence (/sɪˈnɛsəns/) or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics in living organisms. Whole organism senescence involves an increase in death rates or a decrease in fecundity with increasing age, at least in the later part of an organism's life cycle.[1][2] However, the resulting effects of senescence can be delayed. The 1934 discovery that calorie restriction can extend lifespans by 50% in rats, the existence of species having negligible senescence, and the existence of potentially immortal organisms such as members of the genus Hydra have motivated research into delaying senescence and thus age-related diseases. Rare human mutations can cause accelerated aging diseases. Environmental factors may affect aging – for example, overexposure to ultraviolet radiation accelerates skin aging. Different parts of the body may age at different rates and distinctly, including the brain, the cardiovascular system, and muscle. Similarly, functions may distinctly decline with aging, including movement control and memory. Two organisms of the same species can also age at different rates, making biological aging and chronological aging distinct concepts. Definition and characteristicsOrganismal senescence is the aging of whole organisms. Actuarial senescence can be defined as an increase in mortality or a decrease in fecundity with age. The Gompertz–Makeham law of mortality says that the age-dependent component of the mortality rate increases exponentially with age. Aging is characterized by the declining ability to respond to stress, increased homeostatic imbalance, and increased risk of aging-associated diseases including cancer and heart disease. Aging has been defined as "a progressive deterioration of physiological function, an intrinsic age-related process of loss of viability and increase in vulnerability."[3] In 2013, a group of scientists defined nine hallmarks of aging that are common between organisms with emphasis on mammals:

In a decadal update, three hallmarks have been added, totaling 12 proposed hallmarks: The environment induces damage at various levels, e.g. damage to DNA, and damage to tissues and cells by oxygen radicals (widely known as free radicals), and some of this damage is not repaired and thus accumulates with time.[6] Cloning from somatic cells rather than germ cells may begin life with a higher initial load of damage. Dolly the sheep died young from a contagious lung disease, but data on an entire population of cloned individuals would be necessary to measure mortality rates and quantify aging.[citation needed] The evolutionary theorist George Williams wrote, "It is remarkable that after a seemingly miraculous feat of morphogenesis, a complex metazoan should be unable to perform the much simpler task of merely maintaining what is already formed."[7] Variation among speciesDifferent speeds with which mortality increases with age correspond to different maximum life span among species. For example, a mouse is elderly at 3 years, a human is elderly at 80 years,[8] and ginkgo trees show little effect of age even at 667 years.[9] Almost all organisms senesce, including bacteria which have asymmetries between "mother" and "daughter" cells upon cell division, with the mother cell experiencing aging, while the daughter is rejuvenated.[10][11] There is negligible senescence in some groups, such as the genus Hydra.[12] Planarian flatworms have "apparently limitless telomere regenerative capacity fueled by a population of highly proliferative adult stem cells."[13] These planarians are not biologically immortal, but rather their death rate slowly increases with age. Organisms that are thought to be biologically immortal would, in one instance, be Turritopsis dohrnii, also known as the "immortal jellyfish", due to its ability to revert to its youth when it undergoes stress during adulthood.[14] The reproductive system is observed to remain intact, and even the gonads of Turritopsis dohrnii are existing.[15] Some species exhibit "negative senescence", in which reproduction capability increases or is stable, and mortality falls with age, resulting from the advantages of increased body size during aging.[16] Theories of aging

More than 300 different theories have been posited to explain the nature (mechanisms) and causes (reasons for natural emergence or factors) of aging.[17][additional citation(s) needed] Good theories would both explain past observations and predict the results of future experiments. Some of the theories may complement each other, overlap, contradict, or may not preclude various other theories.[citation needed] Theories of aging fall into two broad categories, evolutionary theories of aging and mechanistic theories of aging. Evolutionary theories of aging primarily explain why aging happens,[18] but do not concern themselves with the molecular mechanism(s) that drive the process. All evolutionary theories of aging rest on the basic mechanisms that the force of natural selection declines with age.[19][20] Mechanistic theories of aging can be divided into theories that propose aging is programmed, and damage accumulation theories, i.e. those that propose aging to be caused by specific molecular changes occurring over time.

The aging process can be explained with different theories. These are evolutionary theories, molecular theories, system theories and cellular theories. The evolutionary theory of ageing was first proposed in the late 1940s and can be explained briefly by the accumulation of mutations (evolution of ageing), disposable soma and antagonistic pleiotropy hypothesis. The molecular theories of ageing include phenomena such as gene regulation (gene expression), codon restriction, error catastrophe, somatic mutation, accumulation of genetic material (DNA) damage (DNA damage theory of aging) and dysdifferentiation. The system theories include the immunologic approach to ageing, rate-of-living and the alterations in neuroendocrinal control mechanisms. (See homeostasis). Cellular theory of ageing can be categorized as telomere theory, free radical theory (free-radical theory of aging) and apoptosis. The stem cell theory of aging is also a sub-category of cellular theories.[citation needed] Evolutionary aging theoriesAntagonistic pleiotropyOne theory was proposed by George C. Williams[7] and involves antagonistic pleiotropy. A single gene may affect multiple traits. Some traits that increase fitness early in life may also have negative effects later in life. But, because many more individuals are alive at young ages than at old ages, even small positive effects early can be strongly selected for, and large negative effects later may be very weakly selected against. Williams suggested the following example: Perhaps a gene codes for calcium deposition in bones, which promotes juvenile survival and will therefore be favored by natural selection; however, this same gene promotes calcium deposition in the arteries, causing negative atherosclerotic effects in old age. Thus, harmful biological changes in old age may result from selection for pleiotropic genes that are beneficial early in life but harmful later on. In this case, selection pressure is relatively high when Fisher's reproductive value is high and relatively low when Fisher's reproductive value is low. Cancer versus cellular senescence tradeoff theory of agingSenescent cells within a multicellular organism can be purged by competition between cells, but this increases the risk of cancer. This leads to an inescapable dilemma between two possibilities—the accumulation of physiologically useless senescent cells, and cancer—both of which lead to increasing rates of mortality with age.[2] Disposable somaThe disposable soma theory of aging was proposed by Thomas Kirkwood in 1977.[1][21] The theory suggests that aging occurs due to a strategy in which an individual only invests in maintenance of the soma for as long as it has a realistic chance of survival.[22] A species that uses resources more efficiently will live longer, and therefore be able to pass on genetic information to the next generation. The demands of reproduction are high, so less effort is invested in repair and maintenance of somatic cells, compared to germline cells, in order to focus on reproduction and species survival.[23] Programmed aging theoriesProgrammed theories of aging posit that aging is adaptive, normally invoking selection for evolvability or group selection. The reproductive-cell cycle theory suggests that aging is regulated by changes in hormonal signaling over the lifespan.[24] Damage accumulation theoriesThe free radical theory of agingOne of the most prominent theories of aging was first proposed by Harman in 1956.[25] It posits that free radicals produced by dissolved oxygen, radiation, cellular respiration and other sources cause damage to the molecular machines in the cell and gradually wear them down. This is also known as oxidative stress. There is substantial evidence to back up this theory. Old animals have larger amounts of oxidized proteins, DNA and lipids than their younger counterparts.[26][27] Chemical damage One of the earliest aging theories was the Rate of Living Hypothesis described by Raymond Pearl in 1928[28] (based on earlier work by Max Rubner), which states that fast basal metabolic rate corresponds to short maximum life span. While there may be some validity to the idea that for various types of specific damage detailed below that are by-products of metabolism, all other things being equal, a fast metabolism may reduce lifespan, in general this theory does not adequately explain the differences in lifespan either within, or between, species. Calorically restricted animals process as much, or more, calories per gram of body mass, as their ad libitum fed counterparts, yet exhibit substantially longer lifespans.[citation needed] Similarly, metabolic rate is a poor predictor of lifespan for birds, bats and other species that, it is presumed, have reduced mortality from predation, and therefore have evolved long lifespans even in the presence of very high metabolic rates.[29] In a 2007 analysis it was shown that, when modern statistical methods for correcting for the effects of body size and phylogeny are employed, metabolic rate does not correlate with longevity in mammals or birds.[30] With respect to specific types of chemical damage caused by metabolism, it is suggested that damage to long-lived biopolymers, such as structural proteins or DNA, caused by ubiquitous chemical agents in the body such as oxygen and sugars, are in part responsible for aging. The damage can include breakage of biopolymer chains, cross-linking of biopolymers, or chemical attachment of unnatural substituents (haptens) to biopolymers.[citation needed] Under normal aerobic conditions, approximately 4% of the oxygen metabolized by mitochondria is converted to superoxide ion, which can subsequently be converted to hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical and eventually other reactive species including other peroxides and singlet oxygen, which can, in turn, generate free radicals capable of damaging structural proteins and DNA.[6] Certain metal ions found in the body, such as copper and iron, may participate in the process. (In Wilson's disease, a hereditary defect that causes the body to retain copper, some of the symptoms resemble accelerated senescence.) These processes termed oxidative stress are linked to the potential benefits of dietary polyphenol antioxidants, for example in coffee,[31] and tea.[32] However their typically positive effects on lifespans when consumption is moderate[33][34][35] have also been explained by effects on autophagy,[36] glucose metabolism[37] and AMPK.[38] Sugars such as glucose and fructose can react with certain amino acids such as lysine and arginine and certain DNA bases such as guanine to produce sugar adducts, in a process called glycation. These adducts can further rearrange to form reactive species, which can then cross-link the structural proteins or DNA to similar biopolymers or other biomolecules such as non-structural proteins. People with diabetes, who have elevated blood sugar, develop senescence-associated disorders much earlier than the general population, but can delay such disorders by rigorous control of their blood sugar levels. There is evidence that sugar damage is linked to oxidant damage in a process termed glycoxidation. Free radicals can damage proteins, lipids or DNA. Glycation mainly damages proteins. Damaged proteins and lipids accumulate in lysosomes as lipofuscin. Chemical damage to structural proteins can lead to loss of function; for example, damage to collagen of blood vessel walls can lead to vessel-wall stiffness and, thus, hypertension, and vessel wall thickening and reactive tissue formation (atherosclerosis); similar processes in the kidney can lead to kidney failure. Damage to enzymes reduces cellular functionality. Lipid peroxidation of the inner mitochondrial membrane reduces the electric potential and the ability to generate energy. It is probably no accident that nearly all of the so-called "accelerated aging diseases" are due to defective DNA repair enzymes.[39][40] It is believed that the impact of alcohol on aging can be partly explained by alcohol's activation of the HPA axis, which stimulates glucocorticoid secretion, long-term exposure to which produces symptoms of aging.[41] DNA damageDNA damage was proposed in a 2021 review to be the underlying cause of aging because of the mechanistic link of DNA damage to nearly every aspect of the aging phenotype.[42] Slower rate of accumulation of DNA damage as measured by the DNA damage marker gamma H2AX in leukocytes was found to correlate with longer lifespans in comparisons of dolphins, goats, reindeer, American flamingos and griffon vultures.[43] DNA damage-induced epigenetic alterations, such as DNA methylation and many histone modifications, appear to be of particular importance to the aging process.[42] Evidence for the theory that DNA damage is the fundamental cause of aging was first reviewed in 1981.[44] Mutation accumulationNatural selection can support lethal and harmful alleles, if their effects are felt after reproduction. The geneticist J. B. S. Haldane wondered why the dominant mutation that causes Huntington's disease remained in the population, and why natural selection had not eliminated it. The onset of this neurological disease is (on average) at age 45 and is invariably fatal within 10–20 years. Haldane assumed that, in human prehistory, few survived until age 45. Since few were alive at older ages and their contribution to the next generation was therefore small relative to the large cohorts of younger age groups, the force of selection against such late-acting deleterious mutations was correspondingly small. Therefore, a genetic load of late-acting deleterious mutations could be substantial at mutation–selection balance. This concept came to be known as the selection shadow.[45] Peter Medawar formalised this observation in his mutation accumulation theory of aging.[46][47] "The force of natural selection weakens with increasing age—even in a theoretically immortal population, provided only that it is exposed to real hazards of mortality. If a genetic disaster... happens late enough in individual life, its consequences may be completely unimportant". Age-independent hazards such as predation, disease, and accidents, called 'extrinsic mortality', mean that even a population with negligible senescence will have fewer individuals alive in older age groups. Other damageA study concluded that retroviruses in the human genomes can become awakened from dormant states and contribute to aging which can be blocked by neutralizing antibodies, alleviating "cellular senescence and tissue degeneration and, to some extent, organismal aging".[48] Stem cell theories of agingThe stem cell theory of aging postulates that the aging process is the result of the inability of various types of stem cells to continue to replenish the tissues of an organism with functional differentiated cells capable of maintaining that tissue's (or organ's) original function. Damage and error accumulation in genetic material is always a problem for systems regardless of the age. The number of stem cells in young people is very much higher than older people and thus creates a better and more efficient replacement mechanism in the young contrary to the old. In other words, aging is not a matter of the increase in damage, but a matter of failure to replace it due to a decreased number of stem cells. Stem cells decrease in number and tend to lose the ability to differentiate into progenies or lymphoid lineages and myeloid lineages. Maintaining the dynamic balance of stem cell pools requires several conditions. Balancing proliferation and quiescence along with homing (See niche) and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells are favoring elements of stem cell pool maintenance while differentiation, mobilization and senescence are detrimental elements. These detrimental effects will eventually cause apoptosis. There are also several challenges when it comes to therapeutic use of stem cells and their ability to replenish organs and tissues. First, different cells may have different lifespans even though they originate from the same stem cells (See T-cells and erythrocytes), meaning that aging can occur differently in cells that have longer lifespans as opposed to the ones with shorter lifespans. Also, continual effort to replace the somatic cells may cause exhaustion of stem cells.[49]

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) regenerate the blood system throughout life and maintain homeostasis.[50] DNA strand breaks accumulate in long term HSCs during aging.[51][52] This accumulation is associated with a broad attenuation of DNA repair and response pathways that depends on HSC quiescence.[52] DNA ligase 4 (Lig4) has a highly specific role in the repair of double-strand breaks by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Lig4 deficiency in the mouse causes a progressive loss of HSCs during aging.[53] These findings suggest that NHEJ is a key determinant of the ability of HSCs to maintain themselves over time.[53]

A study showed that the clonal diversity of stem cells that produce blood cells gets drastically reduced around age 70 to a faster-growing few, substantiating a novel theory of ageing which could enable healthy aging.[54][55]

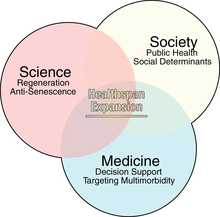

A 2022 study showed that blood cells' loss of the Y chromosome in a subset of cells, called 'mosaic loss of chromosome Y' (mLOY) and reportedly affecting at least 40% of 70 years-old men to some degree, contributes to fibrosis, heart risks, and mortality in a causal way.[56][57] Biomarkers of agingIf different individuals age at different rates, then fecundity, mortality, and functional capacity might be better predicted by biomarkers than by chronological age.[58][59] However, graying of hair,[60] face aging, skin wrinkles and other common changes seen with aging are not better indicators of future functionality than chronological age. Biogerontologists have continued efforts to find and validate biomarkers of aging, but success thus far has been limited. Levels of CD4 and CD8 memory T cells and naive T cells have been used to give good predictions of the expected lifespan of middle-aged mice.[61] Aging clocksThere is interest in an epigenetic clock as a biomarker of aging, based on its ability to predict human chronological age.[62] Basic blood biochemistry and cell counts can also be used to accurately predict the chronological age.[63] It is also possible to predict the human chronological age using transcriptomic aging clocks.[64] There is research and development of further biomarkers, detection systems and software systems to measure biological age of different tissues or systems or overall. For example, a deep learning (DL) software using anatomic magnetic resonance images estimated brain age with relatively high accuracy, including detecting early signs of Alzheimer's disease and varying neuroanatomical patterns of neurological aging,[65] and a DL tool was reported as to calculate a person's inflammatory age based on patterns of systemic age-related inflammation.[66] Aging clocks have been used to evaluate impacts of interventions on humans, including combination therapies.[67][additional citation(s) needed] Exmploying aging clocks to identify and evaluate longevity interventions represents a fundamental goal in aging biology research. However, achieving this goal requires overcoming numerous challenges and implementing additional validation steps.[68][69] Genetic determinants of agingA number of genetic components of aging have been identified using model organisms, ranging from the simple budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to worms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster). Study of these organisms has revealed the presence of at least two conserved aging pathways. Gene expression is imperfectly controlled, and it is possible that random fluctuations in the expression levels of many genes contribute to the aging process as suggested by a study of such genes in yeast.[70] Individual cells, which are genetically identical, nonetheless can have substantially different responses to outside stimuli, and markedly different lifespans, indicating the epigenetic factors play an important role in gene expression and aging as well as genetic factors. There is research into epigenetics of aging. The ability to repair DNA double-strand breaks declines with aging in mice[71] and humans.[72] A set of rare hereditary (genetics) disorders, each called progeria, has been known for some time. Sufferers exhibit symptoms resembling accelerated aging, including wrinkled skin. The cause of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome was reported in the journal Nature in May 2003.[73] This report suggests that DNA damage, not oxidative stress, is the cause of this form of accelerated aging. A study indicates that aging may shift activity toward short genes or shorter transcript length and that this can be countered by interventions.[74] Healthspans and aging in society   Healthspan can broadly be defined as the period of one's life that one is healthy, such as free of significant diseases[76] or declines of capacities (e.g. of senses, muscle, endurance and cognition).

With aging populations, there is a rise of age-related diseases which puts major burdens on healthcare systems as well as contemporary economies or contemporary economics and their appendant societal systems. Healthspan extension and anti-aging research seek to extend the span of health in the old as well as slow aging or its negative impacts such as physical and mental decline. Modern anti-senescent and regenerative technology with augmented decision making could help "responsibly bridge the healthspan-lifespan gap for a future of equitable global wellbeing".[77] Aging is "the most prevalent risk factor for chronic disease, frailty and disability, and it is estimated that there will be over 2 billion persons age > 60 by the year 2050", making it a large global health challenge that demands substantial (and well-orchestrated or efficient) efforts, including interventions that alter and target the inborn aging process.[78] Biological aging or the LHG comes with a great cost burden to society, including potentially rising health care costs (also depending on types and costs of treatments).[75][79] This, along with global quality of life or wellbeing, highlight the importance of extending healthspans.[75] Many measures that may extend lifespans may simultaneously also extend healthspans, albeit that is not necessarily the case, indicating that "lifespan can no longer be the sole parameter of interest" in related research.[80] While recent life expectancy increases were not followed by "parallel" healthspan expansion,[75] awareness of the concept and issues of healthspan lags as of 2017.[76] Scientists have noted that "[c]hronic diseases of aging are increasing and are inflicting untold costs on human quality of life".[79] InterventionsLife extension is the concept of extending the human lifespan, either modestly through improvements in medicine or dramatically by increasing the maximum lifespan beyond its generally-settled biological limit of around 125 years.[81] Several researchers in the area, along with "life extensionists", "immortalists", or "longevists" (those who wish to achieve longer lives themselves), postulate that future breakthroughs in tissue rejuvenation, stem cells, regenerative medicine, molecular repair, gene therapy, pharmaceuticals, and organ replacement (such as with artificial organs or xenotransplantations) will eventually enable humans to have indefinite lifespans through complete rejuvenation to a healthy youthful condition (agerasia[82]). The ethical ramifications, if life extension becomes a possibility, are debated by bioethicists. The sale of purported anti-aging products such as supplements and hormone replacement is a lucrative global industry. For example, the industry that promotes the use of hormones as a treatment for consumers to slow or reverse the aging process in the US market generated about $50 billion of revenue a year in 2009.[83] The use of such hormone products has not been proven to be effective or safe.[83][84][85][86]See also

References

External linksLook up senescence in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Senescence. |