|

Shah Shujah Durrani

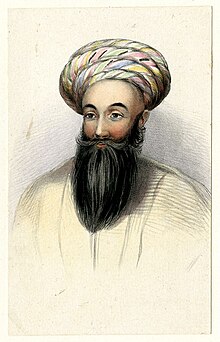

Shah Shujah Durrani (Pashto/Persian: شاه شجاع درانی ; November 1785 – 5 April 1842) was ruler of the Durrani Empire from 1803 to 1809. He then ruled from 1839 until his death in 1842. Son of Timur Shah Durrani, Shujah was of the Sadduzai line of the Abdali group of ethnic Pashtuns. He became the fifth King of the Durrani Empire.[1] LifeFirst reignShujah was the governor of Herat and Peshawar from 1798 to 1801. He proclaimed himself King of Afghanistan in October 1801 (after the deposition of his brother Zaman Shah), but only properly ascended to the throne on July 13, 1803. In Afghanistan, a blind man by tradition cannot be Emir, and so Shujah's step-brother Mahmud Shah had Zaman blinded, however not killed.[2] After coming to power in 1803, Shujah ended the blood feud with the powerful Barakzai family and also forgave them. To create an alliance with them, he married their "sister" Wafa Begum.[3]  In 1809, Shujah allied Afghanistan with British India, as a means of defending against an invasion of Afghanistan and the Punjab Region by France.[4] In 1809, a British diplomatic mission was sent to Afghanistan, which at the time was to the British a remote and mysterious part of Asia. According to Mountstuart Elphinstone, "The King of Kabul [Shah Shujah] was a handsome man". He also wrote "of an olive complexion with a thick black beard ... his voice clear, his address princely." Shujah wore the Koh-i-Noor ("Mountain of Light") diamond in one of his bracelets when Elphinstone visited him, but rather undiplomatically described Shujah as having a "vulgar nose".[5] William Fraser, who accompanied Elphinstone to meet Shah Shujah was "struck with the dignity of his appearance and the romantic Oriental awe."[6] Fraser also judged him to be "about five feet six inches (168 cm) tall" and his skin colour was "very fair, but dead...his beard was thick jet black and shortened a little by the obliquely upwards, but turned again at the corners ... The eyelashes and the edges of his eyelids were blackened with antimony." He also described Shujah's voice as "loud and sonorous".[7]

In June 1809,[8] he was overthrown by his predecessor Mahmud Shah in the battle of Nimla, and went into exile in The Punjab, where he was captured by Jahandad Khan Bamizai and imprisoned at Attock (1811–1812) and then taken to Kashmir (1812–1813) by Atta Muhammad Khan. When Mahmud Shah's vizier Fateh Khan invaded Kashmir alongside Ranjit Singh's army, Shujah chose to leave with the Sikh army. He stayed in Lahore from 1813 to 1814. During his time in India, Shujah was imprisoned and forced to give up the Timur Ruby, Koh-i-Noor, and the sister diamond Dray-i-Nur to Ranjit Singh .[9] He escaped from Ranjit's detention at the Mubarek Haveli Lahore for Ludhiana and the East India Company.[10] From 1818 onward, Shujah who liked to live in a lavish style with his wives and concubines had collected a pension from the East India Company, which thought Shujah might prove useful one day.[11] Shujah stayed first in Ludhiana where he was joined by Zeman Shah in 1821. The place where he stayed in Ludhiana was occupied by the Main Post Office near Mata Rani Chowk and inside it there used to be a white marble stone commemorating his stay there.[12] Exile During his time in exile, Shujah indulged his cruelty by removing the noses, ears, tongues, penises, and testicles of his courtiers and slaves when they displeased him in the slightest.[13] When the American adventurer Dr. Josiah Harlan visited Shujah's court in exile, he noted that all of Shujah's courtiers and slaves were missing some part of their bodies as all had in some way displeased their master at some point along the line — and yet they were all slavishly devoted to him — as Harlan noted that there was an "earless assemblage of mutes and eunuchs in the ex-king's service".[13] When Shujah went out for a picnic with his four wives and the wind blew down his tent, Shujah flew into a rage and, much to Harlan's horror, he had the man responsible for putting up his tent, Khwajah Mika—a slave from East Africa who had already had his ears chopped off—to be castrated on the spot.[13] Shujah's grand vizier, Mullah Shakur, had grown his hair long to cover up that both his ears had been chopped off, and he spoke in the distinctive high-pitched voice of a eunuch; Harlan noted he was lucky as the rest of his body was still intact.[13] Despite or perhaps because he was mutilated, Shujah's grand vizier took a great deal of pleasure in mutilating others and was always inciting his master to have somebody mutilated.[13] Harlan commented on "the grace and dignity of His Highness's demeanor", observing the sense of power he projected, but also that "years of disappointment had created in the countenance of the ex-King an appearance of melancholy and resignation."[14] Harlan, a man without much military experience and knowledge of Pashto, offered to lead an invasion of Afghanistan to restore Shujah, an offer that led the former monarch to break "into a poetical effusion in praise of Kabul" and its gardens, its trees laden with fruits, and its music, culminating with "Kabul is called the Crown of the Air. I pray for the possession of those pleasures which my native country alone can afford".[15] When Harlan pressed him on whether he wanted to accept his offer or not, Shujah agreed.[15] Harlan had a tailor sew up an American flag, which Harlan hoisted up in Ludhiana, and started to recruit mercenaries for the invasion of Afghanistan, suggesting that he was working for the U.S. government (which he was not).[16] Harlan ultimately grew disillusioned with Shujah, writing that he did not view him as the "legitimate monarch, the victim of treasonable practices", but rather as "a wayward tyrant, inflexible in moods, vindictive in his enmities, faithless in his attachments, unnatural in his affections. He remembered his misfortunes only to avenge them".[17] In 1833, Shujah struck a deal with Ranjit Singh of Punjab where he was allowed to march his troops through Punjab, and in return, he would cede Peshawar to the Sikhs if they could manage to take it. In a concerted campaign, the following year, Shujah marched on Kandahar, while the Sikhs commanded by General Hari Singh Nalwa, attacked Peshawar. In July, Shujah was defeated at Kandahar by an alliance between the Qandahar Sardars and Dost Mohammad Khan. Shujah fled. The Sikhs for their part reclaimed Peshawar.[18] Restoration of power In 1838, Shujah had gained the support of the British and Ranjit Singh for wresting power from Dost Mohammad Khan. George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland, believed that most Afghans would welcome the return of Shujah as their rightful ruler, but in fact, by 1838, most people in Afghanistan could not remember him, and those that did, remembered him as a cruel, tyrannical ruler and absolutely hated him.[19] During the march on Kabul, the main British camp was attacked by a force of Ghazis, of whom 50 were captured.[20] When the prisoners were brought before Shujah, one of them used a knife, hidden in his robes, to stab one of Shujah's ministers to death, causing Shujah to fly into one of his rages and order all 50 prisoners to be beheaded on the spot.[20] The British historian, Sir John William Kaye wrote the "wanton barbarity" of the mass execution as all 50 prisoners were beheaded strained the campaign, stating the "shrill cry" of the prisoners as they waited to be executed, was the "funeral wail" of the "unholy policy" of attempting to restore Shujah.[20] Shujah was restored to the throne by the British with the help of the Sikhs, on August 7, 1839,[21] 30 years after his deposition. He did not, however, remain long in power when the British and Sikhs left. Upon being restored, Shujah announced that he considered his own people "dogs" who needed to be taught how to be obedient to their master. He generally shut himself away in Bala Hissar,[citation needed] the citadel of Kabul, and spent his time exacting bloody vengeance on those Afghans whom he felt had betrayed him, making him extremely unpopular with his people.[22] AssassinationObliged by religious pressure, he mustered an army near Kabul on April 4, 1842, notionally to launch an attack on the British. Having been passed over for a command in this expedition, his godson Shujah ud-Daula ("Shoojah Adowlah"), son of his nawab Muhammad Zaman Khan ("vizier" or "nawaub Zeman Khan"), led a gang that ambushed and assassinated the shah the next day. In particular, Shujah ud-Daula had been urged in this course by his Usman Khan ("Oosman Khan").[23][24][25] ReferencesCitations

Sources

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Shuja Shah Durrani. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||