|

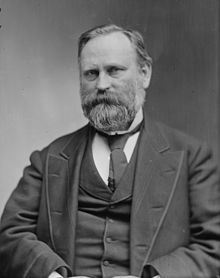

Stanley Matthews (judge)

Thomas Stanley Matthews (July 21, 1824 – March 22, 1889), known as Stanley Matthews in adulthood,[2] was an American attorney, soldier, judge and Republican senator from Ohio who became an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from May 1881 to his death in 1889. A progressive justice,[citation needed] he was the author of the landmark rulings Yick Wo v. Hopkins and Ex parte Crow Dog Early life and educationMatthews was born July 21, 1824, in Cincinnati, Ohio.[a] He was the oldest of 11 children born to Thomas J. Matthews and Isabella Brown Matthews (his second wife).[2] He graduated from Kenyon College in 1840. While there he met future president of the United States Rutherford B. Hayes and close friend John Celivergos Zachos. Matthews moved to his hometown Cincinnati with Zachos. Zachos and Matthews were roommates. In Cincinnati Matthews studied law under Salmon P. Chase but he moved to Columbia, Tennessee, where he practiced law and edited the local newspaper from 1842 and 1844. Matthews returned to Cincinnati in 1844, and was admitted to the bar the following year.[2] In Cincinnati Matthews edited the antislavery newspaper Cincinnati Morning Herald and practiced law from 1853 to 1858.[4][5] In 1849, Stanley Matthews, John Celivergos Zachos, Ainsworth Rand Spofford and 9 others founded the Literary Club of Cincinnati. One year later Rutherford B. Hayes became a member. Other prominent members included future President William Howard Taft and notable club guests Ralph Waldo Emerson, Booker T. Washington, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde and Robert Frost.[6] Early legal careerMatthews was selected to serve as the clerk of the Ohio House of Representatives in 1848, and afterward served as a county judge in Hamilton County, Ohio. He was then elected to the Ohio State Senate for the 1st district, where he served from 1856 to 1858. He was then appointed as United States Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio, serving from 1858 to 1861. Military serviceAt the outbreak of the American Civil War, Matthews resigned as U.S. Attorney and accepted a commission as lieutenant colonel with the 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment of the Union Army.[7] His superior officers included Colonel William S. Rosecrans and Major Rutherford B. Hayes, who would later become President of the United States.[8][9] The regiment also included future President William McKinley, who served as a private and later rose to the rank of major.[8][9] Matthews served with the 23rd Ohio Infantry during the early campaigns in West Virginia and fought at the Battle of Carnifex Ferry on September 10, 1861.[8][9][10] But Matthews did not enjoy the respect of his troops, and within a year he resigned from the 23rd Ohio Infantry.[8] After leaving the 23rd Ohio Infantry, Matthews was appointed colonel of the 51st Ohio Infantry Regiment in 1862.[11] He commanded a brigade in the Army of the Ohio, which later became known as the Army of the Cumberland.[7] State judge, lawyer and politicianIn 1863, Matthews resigned from the Union Army and returned to Ohio, where he was elected judge of the Superior Court of Cincinnati.[7] Two years later, he returned to private practice. During the post-war reconstruction era, Matthews represented the railroad industry. His clients included Jay Gould.[12] He ran for the United States House of Representatives in 1876, but was defeated. Then, in early 1877, he represented Rutherford B. Hayes before the electoral commission that Congress created to resolve the disputed 1876 presidential election.[12] That same year Matthews won a special election to the Senate to fill a vacancy created by the resignation of John Sherman. He did not seek reelection. Associate justiceMatthews was initially nominated an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court on January 26, 1881, by President Hayes[13] in the last weeks of Hayes's presidency. The nomination ran into opposition in the U.S. Senate because of Matthews's close ties to railroad interests and due to his close long-term friendship with Hayes. Consequently, the Judiciary Committee took no action on the nomination during the remainder of the 46th Congress.[14][15] On March 14, 1881, 10 days after taking office, President James A. Garfield re-nominated Matthews to the Court.[13] Though a new nomination from a new president, earlier concerns about Matthews's suitability for the Court persisted, and Garfield was widely criticized for re-submitting Matthews's name.[14] In spite of the opposition, and, although the Judiciary Committee made a recommendation to the Senate that it reject the nomination,[16] on May 12, the Senate voted 24–23 to confirm Matthews. The vote was the closest for any successful Supreme Court nominee in U.S. Senate history;[b] no other justice has been confirmed by a single vote.[13][15][18] Matthews's tenure as a member of the Supreme Court began on May 17, 1881, when he took the judicial oath, and ended March 22, 1889, upon his death.[1][12] He was regarded as one of the more progressive justices on the Court at the time.[18] Yick Wo v. HopkinsIn 1880, the city of San Francisco, California passed an ordinance that persons could not operate a laundry in a wooden building without a permit from the Board of Supervisors. The ordinance conferred upon the Board of Supervisors the discretion to grant or withhold the permits. At the time, about 95% of the city's 320 laundries were operated in wooden buildings. Approximately two-thirds of those laundries were owned by Chinese persons. Although most of the city's wooden building laundry owners applied for a permit, none were granted to any Chinese owner, while virtually all non-Chinese applicants were granted a permit. Yick Wo (益和, Pinyin: Yì Hé, Americanization: Lee Yick), who had lived in California and had operated a laundry in the same wooden building for many years and held a valid license to operate his laundry issued by the Board of Fire-Wardens, continued to operate his laundry and was convicted and fined $10.00 for violating the ordinance. He sued for a writ of habeas corpus after he was imprisoned in default for having refused to pay the fine. The Court, in a unanimous opinion written by Justice Matthews, found that the administration of the statute in question was discriminatory and that there was therefore no need to even consider whether the ordinance itself was lawful. Even though the Chinese laundry owners were usually not American citizens, the court ruled they were still entitled to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Matthews also noted that the court had previously ruled that it was acceptable to hold administrators of the law liable when they abused their authority. He denounced the law as a blatant attempt to exclude Chinese from the laundry trade in San Francisco, and the court struck down the law, ordering dismissal of all charges against other laundry owners who had been jailed. Personal lifeIn 1843, Matthews married Mary Ann "Minnie" Black. They had 10 children, four of whom died during an outbreak of scarlet fever in 1859.[2] Over a three-week period, the outbreak claimed the lives of their three eldest sons (nine-year-old Morrison, six-year-old Stanley, and four-year-old Thomas) as well as younger daughter Mary (age two-and-a-half). Oldest daughter Isabella (seven at the time) and baby William Mortimer survived the devastating outbreak, although Isabella would die in 1868 at the age of sixteen. Their four younger children (Grace, Eva, Jane, and another son named Stanley, later called Paul) were born after the scarlet fever outbreak.[19] "Minnie" died in Washington, D.C., on January 22, 1885, at age 63.[20] Matthews married Mary K. Theaker, widow of Thomas Clarke Theaker, on June 23, 1886, in New York.[21] Death and legacyMatthews's health declined precipitously during 1888; he died in Washington, D.C., on March 22, 1889.[22][23] He was survived by second wife Mary, as well as five of his children with Minnie: Mortimer, Grace, Eva, Jane, and Paul.[24] He is interred at Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio.[25][26] Daughter Jane Matthews married her late father's colleague on the Court, Associate Justice Horace Gray, on June 4, 1889.[27] Daughter Eva Lee Matthews became a schoolteacher and monastic, founding the Community of the Transfiguration, which engaged in charity work in Ohio, Hawaii and in China, leading to her liturgical commemoration in the Episcopal Church.[28] Son Paul Clement was bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey from 1915 to 1937. His son, Justice Matthews's grandson, Thomas Stanley, was editor of Time magazine from 1949 to 1953.[29][30] A collection of Justice Matthews's correspondence and other papers is located at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center library in Fremont, Ohio and open for research. Additional papers and collections are at: Cincinnati Historical Society, Cincinnati, Ohio; Library of Congress, Manuscript and Prints & Photographs Divisions, Washington, D.C.; Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio; Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, New York; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Archives Division, Madison, Wisconsin; and Mississippi State Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.[31] See alsoNotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Stanley Matthews.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||