|

The Modern Theatre Is the Epic Theatre

Conceptualised by 20th century German director and theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), "The Modern Theatre Is the Epic Theatre" is a theoretical framework implemented by Brecht in the 1930s, which challenged and stretched dramaturgical norms in a postmodern style.[1] This framework, written as a set of notes to accompany Brecht's satirical opera, ‘Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’, explores the notion of "refunctioning" and the concept of the Separation of the Elements.[2] This framework was most proficiently characterised by Brecht's nihilistic anti-bourgeois attitudes that “mirrored the profound societal and political turmoil of the Nazi uprising and post WW1 struggles”.[3] Brecht's presentation of this theatrical structure adopts a style that is austere, utilitarian and remains instructional rather than systematically categorising itself as a form that is built towards a more entertaining and aesthetic lens.[4] ‘The Modern Theatre Is the Epic Theatre’ incorporates early formulations of Brechtian conventions and techniques such as Gestus and the V-Effect (or Verfremdungseffekt). It employs an episodic arrangement rather than a traditional linear composition and encourages an audience to see the world as it is regardless of the context.[5] The purpose of this new avant-garde outlook on theatrical performance aimed to “exhort the viewer to greater political vigilance, bringing the Marxist objective of a classless utopia closer to realisation”.[5] Influences and Context Born in Augsburg, Bavaria (February 10, 1898), Bertolt Brecht's upbringing and involvement in the Marxist revolution was highly significant in shaping his ‘Epic Theatre’ conventions and techniques.[6] Epic Theatre’ is known as the “umbrella phrase Brecht used to describe all the technical devices and methods of interpretation that contributed to the creation of an artistic socialist commentary and engaged the spectActor”.[7] During his youth, Brecht studied at the University of Munich, majoring in medicine and he also worked in Augsburg as a medical assistant in a military hospital. During the outbreak of the first World War, Brecht watched his own patients avidly enlist in the army which prompted him to become a radical opponent of war and the nationalistic attitudes associated with it.[8] However, in 1926, with the launch of one of Brecht's earlier agitprop works, ‘A Mans A Man’, he had already established himself as a well-known playwright in the artistic world. Brecht's prospective agitprop displays were informed by Hans Eisler's agitprop principles, as staging didactic and rapid events became the equivalent to offering a visceral radicalisation of the proletariat under totalitarian authority.[8] As Brecht became more progressive, he developed himself into a multifaceted theatre practitioner, breaking apart from expressionistic trends as he started to experiment with new dramaturgical forms which ultimately set precedent for ‘The Modern Theatre’.[9] Brecht's political voice was strengthened by the constitutional and social upheaval that he faced as a proletariat citizen during the time of war and post Hitlers uprising.[10] This came with the emergence of opposing Marxist and Communist ideologies, particularly the influence of the dissident Karl Korsch and anti-Stalinist Walter Benjamin which prompted the emergence of Brecht's theory of aesthetics (guided by Korsch's Marxist dialectic) and set paradigm for his new theatrical presentation.[11] However, Korsch didn't only have significant effect on Brecht's understanding of Marxian dialectics, but the Marxist concepts that were most beneficial for Brecht's practise were the same ideas that they shared in their understanding revolutionary practise.[12]  Although Brecht was predominantly influenced by various poets, writers and other practitioners, his lens on modernist philosophy was heavily governed by Karl Marx. Marx is viewed as the “great contributor who unified scattered trains of socialist thought into a coherent ideology”.[13] Within this ideology, Marx presented the notion of ‘alienation’ as being crucial in truly understanding his theory as he aimed to contextualise through his art what was happening at that particular point in time.[14] His definition of alienation comes from the belief that “work serves as the essence of human nature. Marx argued that who we are stems from what we do”.[10] Under the capitalist regime, Marx asserted that people were forcefully detached from their labour, desensitised from artistic and creative expression and alienated from tangible forums of theatre. He labelled this mode of alienation through examining four fundamental concepts; “first, alienation from the product of labor; second, alienation from the activity of labor; third, alienation from one’s own humanity; and fourth, alienation from society”.[10] While Marxist philosophy dominates the majority of Brechtian theatre, its impact extends beyond the story's subject. Based on a myriad of political events, within the modern framework of theatrical performance Brecht endowed to provide a reactionary response to other arguments provided by authors, writers and critics of his industry. Similarly to how Marx acknowledged the concepts of other philosophers such as Hegel's view on world history, epic theatre as modern establishment rejected the Westernised aesthetic of performance as originally initiated by Aristotle.[12] Aristotle's analysis in what was known as the ‘Poetics’ is the “thesis, with epic theatre the antithesis”.[11] The parallel between Marxist theory and epic theatre shapes the overall approach to representing the marginalisation of the proletariat class structure and aims to signify their peripheral maltreatment via a visual dialogue.[5] These theories coincide and agree that not only contradictions but the struggles faced by the masses are fundamental in supporting the foundation of the modern theatre.[15] Both primarily rely on Marxist poetics and highlight the dialectical link between economics as the foundation. They draw attention to the idea of 'facility', in which awareness is shaped by material interactions and current ideologies.[4] Theoretical Practises During his career, Brecht's theory and practice of theatre had developed immensely as he became more and more fascinated with the emergence of the modernist movement. Particularly when he acquired a Marxist view of society during the early 1930s, Brecht developed a new theatrical notion that was heavily based on German Expressionism but was preoccupied with the idea that man and society could be psychologically and contextually examined.[16] Based on these theatrical convictions, Brecht proposed an alternative route for theatre that merged the functions of didacticism and entertainment.[17] Within this Brecht incorporated Marxist dialectics as he speculates upon the notions of thesis, antithesis and synthesis.[18] These terms are then utilised to examine the epic theatre genre as a piece of instructional drama and encourages a reimagining of conventionalist presentation.[7]  Brecht ensured that his practices would expose his audiences to the repercussions of Nazism and the social injustices that came with it.[7] He wanted to reveal the conceptual similarities between reality itself and the theatre, rather than presenting a climactic catharsis of emotion.[19] Intentionally, he sought to disrupt the customary five act structure of a conventional play, breaking up the main plot, which was originally inspired by the Russian revolutionary theatre.[20] To stifle the audiences natural curiosity, he employed audience-directed comments on the action, songs in between, and text projections with additional information that was aimed to educate them.[21] Brecht then introduced the principle of historicisation, which was fundamental to his theory as it constituted an interpretative attitude (also known as a "grund-gestus").[7] Historicisation presents an event as a product of a particular historical context; paralleling the past to the present, led by Marxist philosophy.[4] Brecht offers a vivid representation of this concept in his speech "Speech to Danish working-class actors on the art of observation"[22]  Brecht's form of the ‘Modern Theatre' was a reaction against the conventional style of performance, particularly Konstantin Stanislavski’s naturalistic approach.[23] Although both Brecht and Stanislavsky opposed the manipulative plots of traditional theatre and the heightened emotional baggage that came with melodrama, Stanislavsky's method to engender real human behaviour influenced Brecht's theoretical practice as he saw Stanislavsky's system as a framework for producing escapism.[24] Brecht's own theatrical progression also departed from surrealism and Antonin Artaud's Theatre of Cruelty, which sought to affect its audiences viscerally, irrationally and psychologically.[25] However Artaud's collection of works concur with Brecht's as they both encourage transformation through a recontextualisation of theatrical perspective and challenge the appropriation of form.[4] Artaudian performance is seen as apolitical and provides an anarchist outlook, entreats collective feeling and evokes an emotional response from the viewer.[26] Contrastingly, Brecht’s epic theatre approach is rational and politically focused. Both practitioners theorise about political and social change as well as diverge in their representation of the actor-audience relationship.[27] Brecht maintained that a man is determined by social conditions and that change should be found first in economic or ideological forces, Artaud argues that reform should begin with the individual.[28] Brecht emphasises the notion that social and cultural being frames meaning, as he reinforces that man should be seen as merely a "process" when distinguishing between dramatic and epic theatre.[5] Although Brecht wrote little on actor training in his extensive analysis of theatre, he wanted his message to clearly come across to his audiences. Brecht demanded that actors needed to function as political and social observers in order to reflect history through an artistic lens.[8] Amidst many of Brecht's dramaturgical innovations, his rehearsal methods established a directing collective, particularly within the Berliner Ensemble which he founded with his wife Helene Weigel in January 1949.[2] However, he immediately clashed with the Stalinist cultural bureaucracy which compelled him to make revisions to several of his productions.[29] By distributing the authority evenly between the director, dramaturge, actor and composer, Brecht's process of rehearsal challenged the standard norms of storytelling and allowed for feedback to refine a play's strongest and weakest characteristics.[30] Bertolt Brecht, as one of the most important figures in the world of theatre, has left an everlasting imprint on his audiences through his distinctive approaches. His search for a political theatre changed him into a modern avant-garde who influenced the creation of new postmodern works.[5] Techniques and MethodologyBrecht's theoretical work of ‘The Modern Theatre Is the Epic Theatre’ employs irregular artistic conventions that subvert traditionalist theatre and aim to alienate the viewer by invoking political and social pedagogy.[14] Brecht invented various techniques such as Separation of Elements, Gestus and the V-Effect to reflect the struggles of a German post war modern society.[2] Separation of ElementsSeparation of Elements is a principle that focuses specifically on performance and the theatrical aesthetic. Its primary objective is to oppose the concept behind the "integrated work of art", proposed by Wagner which refers to various visual forms that seek to make use of other artistic forms.[12] Brecht employs the ‘Separation of Elements’ with his methodology of epic theatre’ to demonstrate his social and political climate during the 20th century.[2] GestusGestus is one of Brecht's most significant theatrical techniques that combines the use of gestic expression and social meaning within a certain movement, vocal display or physical stance.[7] It is used to communicate the thematic and contextual ideas of the play or a specific scene within the play, and highlights a character's relationship with others by revealing their social attitudes.[31] According to theatrologist Meg Mumford, she attains that Brecht labels gestus as “presenting artistically the mutable socioeconomic and ideological construction of human behaviour and emotions” through “moulded and sometimes subconscious body language”.[7] This gestic action becomes transformed into a source of visual narrative that conveys "particular perspectives towards others and their circumstances".[5] V-EffectThe V-Effect (also known as the Verfremdungseffekt) was one of Brecht's earlier techniques that aimed to distance or alienate the audience from connecting to the play from an emotional standpoint.[5] Brecht does this by constantly reminding his audience of the artificiality of theatrical performance by implementing various abrasive reminders that signify to the viewer that they are purely watching a show for educational purposes.[2] Some of the ways he alienates his audience includes; the use of signs and placards, actors speaking the stage directions out loud, use of projection and technology, use of narrator, song and music and breaking the fourth wall.[7] By creating stage effects that were unusual and obscure, Brecht intended to encourage the audience to be active participants rather than passive, forcing them to ask questions about the artificial environment and how each dramatic element coincides with each other to depict real life events on stage.[32] Practical Works and ProductionsMajority of Brechts most notable productions were created during the mid-1920s and late 1940s in which he wrote, produced, cast and directed a comprehensive 31 plays in total that all were constructed and based on the modern epic theatre framework.[22] Some of these include; The Measures Taken, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and The Threepenny Opera. The Threepenny Opera (1928) Defined as a "socialist critique of capitalist life", The Threepenny Opera was another musical drama Brecht did in collaboration with Kurt Weill that focused on the repercussions of living in a capitalist utopia "driving people to do anything to make money".[33] Through an informative yet confronting lens, this production demonstrated the lengths the masses would go to in order to achieve a fruitful living amidst a society that rewards ruthless and competitive behaviour.[33] Created as a reaction towards communism and in favour of the rising proletariat, Brecht and Weill sought to empower the working class, hoping that they would obtain power and reform the corrupt political agenda enforced by the ruling class.[4] Incorporating the conventions of epic theatre, utilising signs, narrative, v-effect and montage, The Three Penny Opera created a setting that shocked the everyday spectator, providing a more rational and authentic perspective on the action.[22] The Measures Taken (1930)‘The Measures Taken’ by Bertolt Brecht - a theatrical phenomena, representative of political change, power and social constructivism, encapsulates the repercussions of living in a totalitarian and capitalist system and exposes the tactics of clandestine agitation within it.[34] This play, among many others, marked the strengthening of Brecht's public voice, pioneering a proletarian theatre that is reflective of the constitutional and social upheaval he faced as German citizen.[34] Through the political characterisation of various characters such as The Control Chorus (who hold the dominant status in the play) and The Four Agitators (who become a product of them), Brecht immediately confronts the notion of repressive collectivism, as the treatment of the lower-class in the play, particularly towards the working class, signify immense proletarian struggle and despotism.[15] Brecht's representation of characters remains cynical, proposing that there is more tyranny present in the world rather than optimism.[15] The classical 15th century western narrative of Taniko (also known as The Valley Hurling) by Zenchiku was one of the biggest influences in Brecht's construction of 'The Measures Taken', relaying a narrative of a Buddhists journey to a sacred mountain, focusing on the purificatory notion of human sacrifice.[35] This representation of the Japanese ‘Noh’ (with the inclusion of the Noh mask) focuses on the theatrical concept of the ‘mission’ which Brecht emulates in his own production through the political characterisation of The Control Chorus, The Four Agitators and The Young Comrade.[29] Adopting a Shitoist structure, Taniko highlights the repercussions of living in a collective hegemony and propagates the shift from individual to social consciousness which later becomes paralleled in ‘The Measures Taken’.[36] Brecht utilises these radical distancing/estranging techniques such as the employment of the verfremdungseffekt to explore the dramatic tensions between political strategy, the notion of obligation and moral integrity in which the conception of individualism becomes blurred.[37] Rise and Fall of the City Mahagonny (1930)A didactic critique of traditional American society, The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny was one of Brecht's most successful productions that was constructed in collaboration with German-American composer Kurt Weill. It projected a cynical view of German civilisation that played on the concept of the ‘modern myth’.[22] It was regarded as a tale of an “imaginary yet plausible town, peopled by fortune seekers, prostitutes and shady businessmen (and women), where absolutely anything goes, except having no money”.[38] This satirical opera blurs the boundaries of theatrical representation as it blends song, rhythm, jazz and drama into a dramatic fusion of character visuals.[2] Brecht wanted to present through a new and unique avenue the functionality of a capitalist society and how people interacted within it.[22] References

|

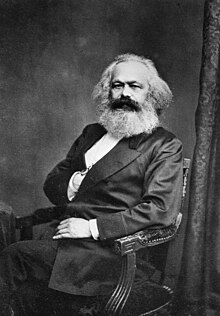

||||||||||||||||