|

The Ten (Expressionists)

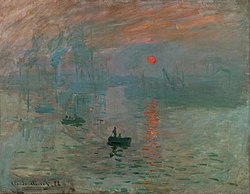

The Ten, also known as The Ten Whitney Dissenters, were a group of New York–based artists active from 1935 to 1940.[1][a] Expressionist in tendency, the group was founded to gain exposure for its members during the economic difficulty of the Great Depression, and also in response to the popularity of Regionalism which dominated the gallery space its members sought. Work exhibited by The Ten included figurative art; however some of its members later rose to prominence as abstract artists. Although short-lived, The Ten were a seminal group, noted by art historians in connection with its members Ilya Bolotowsky, Adolph Gottlieb, and Mark Rothko. Background The tradition of artists jointly exhibiting work outside major venues extends at least as far back as Impressionism; this was typically done to circumvent the dominance of academic art and its associated institutions. Following their repeated rejections from the Salon, the Impressionists formed their own society in 1873—the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs ("Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers")[3]—and began holding independent exhibitions in Paris.[4] In the same vein, an American group of Impressionist artists known as "The Ten" formed in 1897 to exhibit independently of the Society of American Artists and the National Academy of Design, showing regularly in New York and other East Coast cities from 1898 to 1918.[5] Further, another American group known as The Eight[b] showed at the Macbeth Gallery in 1908, similarly to work around the National Academy of Design after certain of its members were not accepted for the Academy's spring 1907 show.[5] Due to overlapping membership and their then-controversial depictions of urban scenery and the life of the working poor in New York, The Eight were closely associated with, but distinct from, The Ashcan school. FormationDuring the mid 1930s, the gallerist Robert Ulrich Godsoe organized a variety of shows to promote American modern art. Head of the exhibition division of the WPA Federal Art Project and director of the Uptown Gallery as of May 1934, Godsoe opened his own gallery in late 1934/early 1935, dubbing it "Gallery Secession" (or: Secession Gallery) after the German and Austrian Secession movements of the 1890s.[6][7] The Secession was short lived however, closing the following summer. According to Joseph Solman, it was during this period that he and a group of fellow artists who had exhibited with Godsoe—including Ilya Bolotowsky, who had not[6]—decided to leave and organize their own exhibitions, naming themselves "The Ten".[8] Despite having taken the same name as the earlier Impressionist group, Solman recalled that the name was chosen simply because "it sounded good", and not as homage to the earlier group.[9] The name was non-literal; at the time of founding there were only nine members, though "the group considered that a tenth man could be easily found at a later date".[10] The size of the group was also motivated by the exhibition opportunities it opened up. The Ten's second show was held at the Municipal Art Gallery, which adopted a policy based on that used for the MacDowell Club exhibitions: any self-organized group of eight to twelve artists could show their work.[11] Similarly, the city government had announced plans for the Municipal Art Gallery to exhibit self-organized groups of ten to fifteen artists.[12] In Solman's account, the decision to start a new group was motivated in part by Godsoe's indiscriminate curation, which he felt diluted the quality of the shows:

Although Godsoe's account of the founding has taken on the status of a standard version,[12] fellow member Yankel "Jack" Kufeld remembered things differently, stressing Godsoe's organizing role as the catalyst for the group's formation:

Louis Schanker- In a letter to Louis Schanker, Ilya Bolotowsky wrote of his vision for the formation of a group of like-minded artists. He asked for Schanker’s assistance because he was well respected in the art community and had a wide circle of friends. Schanker’s list in his sketch pad eventually became the original members of the Ten. Bolotowsky also spoke of this during a memorial service for Schanker in 1981. The Ten held their first work meeting at Solman's studio, the first of the group's monthly meetings to be held regularly for the next five years. Despite the difficulty of showing and selling work during the Depression, The Ten were one among several artists' groups active in 1930s New York, certain of which had left-wing or communist affiliation. The Artists' Union formed in February 1934 and its activities helped precipitate the WPA Federal Art Project; during the same period, The American Artists' Congress formed in 1935, having ties to the American Communist Party. All founding members of The Ten were members of both groups.[13] Despite the politics of related groups, The Ten were primarily motivated by the practical considerations of showing and selling their work. Similarly although their work sometimes touched on social themes, it was not overtly political or doctrinaire—the artists sought new forms of expression which would not imitate European art or American regionalism. As Gottlieb put it,

Exhibitions

The Ten held nine exhibitions of their work, including one international show and a brief art auction benefit. Joseph Solman recalled that after the members tasked themselves with "knocking at many doors with dark photographs of dark paintings", The Ten secured their first show at the Montross Gallery from December 16, 1935 through January 4, 1936. Titled "The Ten: an Independent Group", the exhibition consisted of 36 paintings, four by each of the nine founding members.[11][13][14] Immediately following the first show, the second was held at the Municipal Art Gallery[15] from January 7–18, 1936, alongside other artists. In all one hundred works were shown, including paintings from The Ten on the Gallery's third floor, devoted to modern painting.[11] In the fall the group won its third—and only international—exhibition from November 10–24 at the Parisian Galerie Bonaparte, brokered by art dealer Joseph Brummer.[16] At year's end the group had its fourth and "second annual" show at Montross, from December 14, 1936 – January 2, 1937. By this point founding member Tschacbasov had been "frozen out" owing to "brashness and opportunism", but was replaced by guest artist Lee Gatch.[16] The period following The Ten's first productive year included two exhibitions at the Georgette Passedoit Gallery, the first running from April 26-May 28, 1937, while the latter was a year later, May 9–21, 1938. Between these, the group held a brief art auction from December 3–5, 1937 for the benefit of children affected by the Spanish Civil War. [c] These comprised the group's fifth, sixth and seventh exhibitions. Throughout this period the group's membership changed moderately, with certain guest artists appearing and disappearing from show to show. The eighth and penultimate show was held at Bernard Braddon's Mercury Galleries from November 5–26, 1938, next door to the Whitney Museum of American Art.[20] Itself recently established in 1931, The Whitney was then holding its Annual show (later to become the Whitney Biennial);[21] although most of The Ten sought to participate, only Bolotowsky was successful. During this period the Whitney placed a heavy emphasis on regionalism, social realism and established painters, at the expense of expressionist and abstract work. Thus, The Ten staged their own show in direct competition with the Whitney Annual, titling it "The Ten: Whitney Dissenters".[2] Though marketed as a provocation, the exhibit was still primarily meant to meet the practical goals of showing and selling work, while attracting attention—the group hoped to benefit from the Annual's popularity.[22] The artists also proposed a distinct vision for modern American art, one which was not identical with regionalism. The exhibit's catalogue essay, co-written by Mark Rothko and Bernard Braddon, ran thus:

The Whitney Dissenters show drew more critical attention than any of The Ten's other exhibits. Like the collectives which preceded them, The Ten had staged their own show as an explicit alternative to a particular institution which rejected their work. However, Bolotowsky's simultaneous representation in both shows was noted with irony by critics.[17][22][23] Compared with the Dissenters show, the Ten's ninth and final exhibition "passed relatively unnoticed"[24] at the Bonestell Gallery, from October 23-November 4, 1939. By this point the founders Gottlieb and Harris had departed, and the group had served its purpose: individuals had branched out into personal styles[2] and had established relationships with galleries, and the political tensions of World War II inflamed differences among the members.[25] The Ten ceased functioning as a group in early 1940.[24] MembersOver the course of the group's existence, seventeen[1] artists exhibited as members of The Ten at nine[6] different shows. The founders formed a core membership of nine, at times joined by eight different guest artists on short term bases. Over time, certain of the founders left while participating guest artists kept the group's size at nine or ten for each show. The group's nine shows were held at galleries and locations around New York City, including one international exhibition in Paris. The count of nine shows includes a brief art auction held from December 3–5, 1937, for the benefit of children affected by the Spanish Civil War.[d]

Timeline Exhibited works Members of The Ten exhibited several dozen works at its shows, commonly in equal proportion at a given show.[e] Although some members disliked the descriptor "social realism", earlier works nevertheless dealt with social themes and working class life, subject matter unavoidable during the Depression. To illustrate, the art historian Isabelle Dervaux detailed three pictures from the first Montross exhibition. Lynching by Ben-Zion used expressionistic distortion to convey the horror and confusion of a lynching. Despite his personal ambivalence to social themes and preference for abstraction, Bolotowsky contributed a figurative cubist work—Sweatshop—depicting a seamstress; his mother-in-law was the model. A more placid scene was Adolph Gottlieb's Conference which depicted a meeting of five women, showing the influence of Milton Avery on the group.[26] As the 1930s progressed the group moved away from explicitly social themes and toward urban scenery and abstraction; Dervaux noted several titles describing nocturnes and cityscapes at the Whitney Dissenters exhibit. She also identified Rothko's Interior as an early work which featured coloristic division of space into rectangular forms, anticipating his later color field paintings, an observation repeated by the art historian David Anfam.[27]  In his study of Rothko's paintings, Anfam gave a partial reconstruction of Rothko's contributions to The Ten's shows. The first Montross show included four works: Seated Nude, Woman Sewing, City Phantasy, and Subway. Anfam observed that the grouping had identical recto and verso signatures, uniquely in Rothko's catalogue, and also had pairwise consonances and contrasts, a theme in each artist's group-of-four noted by contemporary critic Herbert Lawrence.[28] Woman Sewing and Subway were both sent to the Paris Bonaparte show, together with Crucifixion, a painting based on Rembrandt's Lamentation which is now lost.[29] Anfam conjectured that Rothko contributed a group of four works to the Spanish war benefit auction; joined by their depictions of girls in cityscapes, he described them as an "oblique embroidery" suggesting child victims of the Spanish Civil War, in keeping with the auction's theme, but without explicitly depicting the war itself.[30] As Dervaux had noted, none of the paintings put up for auction took the war itself for subject matter. CriticismContemporary reception of The Ten's shows ranged from scorn to measured praise; later art historians treated The Ten for its early significance to the artists' careers, and more broadly to the New York School. While Edward Alden Jewell described the group's second Montross exhibit as "inchoate" and "silly smudges", Emily Genauer gave a more positive opinion of the group, praising their "strong inward preoccupation with the quality of painting."[31] Writing in the left-wing review Art Front, Herbert Lawrence gave moderate praise of the group's original Montross show, albeit with reservations.[28] When laborers set up the Municipal Art Gallery exhibit, one gave a negative opinion of Gottlieb's Seated Nude: "No, we don't like it... Why couldn't he paint a good-looking dame?"[32] The fact that The Ten routinely exhibited with nine members was noted with humor by various critics.[14] The art historians Lucy Embick and Isabelle Dervaux later identified The Ten as continuing a tradition of artists' groups breaking away from dominant institutions, citing The Eight and The (earlier) Ten as precursors.[33][34] Notes

Bibliography

Further reading

References

|