|

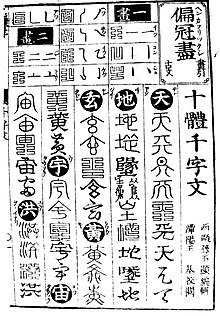

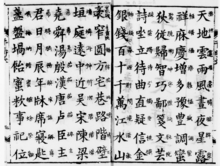

Thousand Character Classic

The Thousand Character Classic (Chinese: 千字文; pinyin: Qiānzì wén), also known as the Thousand Character Text, is a Chinese poem that has been used as a primer for teaching Chinese characters to children from the sixth century onward. It contains exactly one thousand characters, each used only once, arranged into 250 lines of four characters apiece and grouped into four line rhyming stanzas to facilitate easy memorization. It is sung, akin to alphabet songs for phonetic writing systems. Along with the Three Character Classic and the Hundred Family Surnames, it formed the basis of traditional literacy training in the Sinosphere. The first line is Tian di xuan huang (traditional Chinese: 天地玄黃; simplified Chinese: 天地玄黄; pinyin: Tiāndì xuán huáng; Jyutping: Tin1 dei6 jyun4 wong4; lit. 'Heaven earth dark yellow') and the last line, Yan zai hu ye (焉哉乎也; Yān zāi hū yě; Yin1 zoi1 fu4 jaa5) explains the use of the grammatical particles yan, zai, hu, and ye.[1] HistoryThere are several stories of the work's origin. One says that Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty (r. 502–549) commissioned Zhou Xingsi (traditional Chinese: 周興嗣; simplified Chinese: 周兴嗣; pinyin: Zhōu Xìngsì, 470–521) to compose this poem for his prince to practice calligraphy. Another says that the emperor commanded Wang Xizhi, a noted calligrapher, to write out one thousand characters and give them to Zhou as a challenge to make into an ode. Another story is that the emperor commanded his princes and court officers to compose essays and ordered another minister to copy them on a thousand slips of paper, which became mixed and scrambled. Zhou was given the task of restoring these slips to their original order. He worked so intensely to finish doing so overnight that his hair turned completely white.[2] The Thousand Character Classic is understood to be one of the most widely read texts in China in the first millennium.[3] The popularity of the book in the Tang dynasty is shown by the fact that there were some 32 copies found in the Dunhuang archaeological excavations. By the Song dynasty, since all literate people could be assumed to have memorized the text, the order of its characters was used to put documents in sequence in the same way that alphabetical order is used in alphabetic languages.[4] The Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho used the thousand character classic and the Qieyun and it was written that "In Qocho city were more than fifty monasteries, all titles of which are granted by the emperors of the Tang dynasty, which keep many Buddhist texts as Tripitaka, Tangyun, Yupuan, Jingyin etc."[5] In the dynasties following the Song, the Three Character Classic, Hundred Family Surnames, and 1,000 Character Classic came to be known collectively as San Bai Qian (Three, Hundred, Thousand), from the first character in their titles. They were the almost universal introductory literacy texts for students, almost exclusively boys, from elite backgrounds and even for a number of ordinary villagers. Each was available in many versions, printed cheaply, and available to all since they did not become superseded. When a student had memorized all three, he could recognize and pronounce, though not necessarily write or understand the meaning of, roughly 2,000 characters (there was some duplication among the texts). Since Chinese did not use an alphabet, this was an effective, albeit time-consuming, way of giving a "crash course" in character recognition before going on to understanding texts and writing characters.[6] During the Song dynasty, the noted neo-Confucianism scholar Zhu Xi, inspired by the three classics, wrote Xiaoxue or Elementary Learning[citation needed]. CalligraphyDue to the fact that the Thousand Character Classic contains a thousand unique Chinese characters, and its wide circulation, it has been highly favored by calligraphers in East Asian countries. According to the Xuanhe Calligraphy Catalogue (宣和画谱), the Northern Song imperial collection included twenty-three authentic works by Sui dynasty calligrapher Zhiyong (a descendant of Wang Xizhi), fifteen of which were copies of the Thousand Character Classic. Chinese calligraphers such as Chu Suiliang, Sun Guoting, Zhang Xu, Huaisu, Mi Yuanzhang (Northern Song), Emperor Gaozong of Southern Song, Emperor Huizong of Song, Zhao Mengfu, and Wen Zhengming all have notable calligraphic works of the Thousand Character Classic. Manuscripts unearthed from Dunhuang also contain practice fragments of the Thousand Character Classic, indicating that by the 7th century at the latest, using the Thousand Character Classic to practice Chinese calligraphy had become quite widespread. JapanWani, a semi-legendary Chinese-Baekje scholar,[7] is said to have translated the Thousand Character Classic to Japanese along with 10 books of the Analects of Confucius during the reign of Emperor Ōjin (r. 370?-410?). However, this alleged event precedes the composition of the Thousand Character Classic. This makes many assume that the event is simply fiction, but some[who?] believe it to be based in fact, perhaps using a different version of the Thousand Character Classic. KoreaThe Thousand Character Classic has been used as a primer for learning Chinese characters for many centuries. It is uncertain when the Thousand Character Classic was introduced to Korea. The book is noted as a principal force—along with the introduction of Buddhism into Korea—behind the introduction of Chinese characters into the Korean language. Hanja was the sole means of writing Korean until the Hangul script was created under the direction of King Sejong the Great in the 15th century; however, even after the invention of Hangul, most Korean scholars continued to write in Hanja until the late 19th century. The Thousand Character Classic's use as a writing primer for children began in 1583, when King Seonjo ordered Han Ho (1544–1605) to carve the text into wooden printing blocks. The Thousand Character Classic has its own form in representing the Chinese characters. For each character, the text shows its meaning (Korean Hanja: 訓; saegim or hun) and sound (Korean Hanja: 音; eum). The vocabulary to represent the saegim has remained unchanged in every edition, despite the natural evolution of the Korean language since then. However, in the editions Gwangju Thousand Character Classic and Seokbong Thousand Character Classic, both written in the 16th century, there are a number of different meanings expressed for the same character. The types of changes of saegims in Seokbong Thousand Character Classic into those in Gwangju Thousand Character Classic fall roughly under the following categories:

From these changes, replacements between native Korean and Sino-Korean can be found. Generally, "rare saegim vocabularies" are presumed to be pre-16th century, for it is thought that they may be a fossilized form of native Korean vocabulary or affected by the influence of a regional dialect in Jeolla Province. South Korean senior scholar, Daesan Kim Seok-jin (Korean Hangul: 대산 김석진), expressed the significance of Thousand Character Classic by contrasting the Western concrete science and the Asian metaphysics and origin-oriented thinking in which "it is the collected poems of nature of cosmos and reasons behind human life".[8] The first 44 characters of the Thousand Character Classic were used on the reverse sides of some Sangpyeong Tongbo cash coins of the Korean mun currency to indicate furnace or "series" numbers.[9] Vietnam There is a version of Thousand Character Classic that was changed to the Vietnamese lục bát (chữ Hán: 六八) verse form. The text itself is called Thiên tự văn giải âm (chữ Hán: 千字文解音), and it was published in 1890 by Quan Văn Đường (chữ Hán: 觀文堂). The text is annotated with chữ Nôm characters, for example, the character 地 is annotated with its chữ Nôm equivalent 坦. Because it was changed to the lục bát verse form, many characters are changed such as in the first line,[10]

Manchu textsSeveral different Manchu texts of the Thousand Character Classic are known today. They all use the Manchu script to transcribe Chinese characters. They are utilized in research on Chinese phonology. The Man han ciyan dzi wen (simplified Chinese: 满汉千字文; traditional Chinese: 滿漢千字文; pinyin: Mǎn hàn qiān zì wén; Jyutping: mun5 hon3 cin1 zi6 man4) written by Chen Qiliang (simplified Chinese: 沉启亮; traditional Chinese: 沈啓亮; pinyin: Chénqǐliàng; Jyutping: cam4 kai2 loeng6), contains Chinese text and Manchu phonetic transcription. This version was published during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor.[11] Another text, the Qing Shu Qian Zi Wen (simplified Chinese: 清书千字文; traditional Chinese: 清書千字文; pinyin: Qīngshū qiān zì wén; Jyutping: cing1 syu1 cin1 zi6 man4) by You Zhen (Chinese: 尤珍; pinyin: Yóu Zhēn; Jyutping: jau4 zan1), was published in 1685 as a supplement to the Baiti Qing Wen (simplified Chinese: 百体清文; traditional Chinese: 百體清文; pinyin: Bǎi tǐ qīngwén; Jyutping: baak3 tai2 cing1 man4). It provides Manchu transcription without original Chinese. It is known for being referred to by Japanese scholar Ogyū Sorai for Manchu studies as early as the 18th century.[12] The undated ciyan dzi wen which is owned by the Bibliothèque nationale de France is a variant of the Qing Shu Qian Zi Wen. It is believed to have been used by the translation office of the Joseon Dynasty of Korea. It contains Hangul transcription for both Manchu and Chinese.[13] It is valuable to the study of Manchu phonology. Text variantsThe text of the Qiānzì Wén is not available in an authoritative, standardized version. Comparison of various manuscript, printed and electronic editions shows that these do not all contain exactly the same 1,000 characters. In many cases the differences concern just small graphic variations (for example character no. 4, 黃 or 黄, both huáng "yellow"). In other cases variant characters are quite different, although still associated with the same pronunciation and meaning (for example character no. 123, 一 or 壹, both yì "one"). In a few cases, variant characters represent different pronunciations and meanings (for example character no. 132, 竹 zhú "bamboo" or 樹 shù "tree"). These textual variants are not noted or discussed in any existing edition of the text in a western language. In fact, even the text appended to this article differs from the text presented in Wikisource in 25 places (nos. 123 一/壹, 132 竹/樹, 428 郁/鬱, 438 彩/綵, 479 群/羣, 482 稿/稾, 554 回/迴, 617 岳/嶽, 619 泰/恆, 643 綿/緜, 645 岩/巖/, 693 鑒/鑑, 733 沉/沈/, 767 蚤/早, 776 搖/颻, 787 玩/翫, 803 餐/飡, 846 筍/笋, 849 弦/絃, 852 宴/讌, 854 杯/盃, 881 箋/牋, 953 璿/璇, 980 庄/莊). A critical text edition of the Qiānzì Wén, based upon the best manuscript and printed sources, has not yet been attempted. Text

See also

Similar poems in other languages

References

Bibliography

External linksWikisource has original text related to this article:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||