|

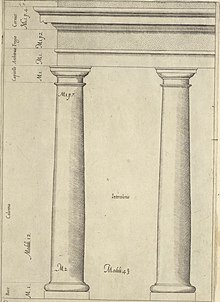

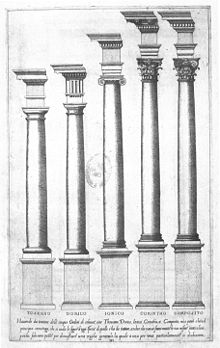

Tuscan order    The Tuscan order (Latin Ordo Tuscanicus or Ordo Tuscanus, with the meaning of Etruscan order) is one of the two classical orders developed by the Romans, the other being the composite order. It is influenced by the Doric order, but with un-fluted columns and a simpler entablature with no triglyphs or guttae. While relatively simple columns with round capitals had been part of the vernacular architecture of Italy and much of Europe since at least Etruscan architecture, the Romans did not consider this style to be a distinct architectural order (for example, the Roman architect Vitruvius did not include it alongside his descriptions of the Greek Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders). Its classification as a separate formal order is first mentioned in Isidore of Seville's 6th-century Etymologiae and refined during the Italian Renaissance.[1] Sebastiano Serlio described five orders including a "Tuscan order", "the solidest and least ornate", in his fourth book[2] of Regole generali di architettura sopra le cinque maniere de gli edifici (1537). Though Fra Giocondo had attempted a first illustration of a Tuscan capital in his printed edition of Vitruvius (1511), he showed the capital with an egg and dart enrichment that belonged to the Ionic. The "most rustic" Tuscan order of Serlio was later carefully delineated by Andrea Palladio. In its simplicity, the Tuscan order is seen as similar to the Doric order, and yet in its overall proportions, intercolumniation and simpler entablature, it follows the ratios of the Ionic. This strong order was considered most appropriate in military architecture and in docks and warehouses when they were dignified by architectural treatment. Serlio found it "suitable to fortified places, such as city gates, fortresses, castles, treasuries, or where artillery and ammunition are kept, prisons, seaports and other similar structures used in war." Italian writers on architectureFrom the perspective of these writers, the Tuscan order was an older primitive Italic architectural form, predating the Greek Doric and Ionic, associated by Serlio with the practice of rustication and the architectural practice of Tuscany.[3] Giorgio Vasari made a valid argument for this claim by reference to Il Cronaca's graduated rustication on the facade of Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.[4] Like all architectural theory of the Renaissance, precedents for a Tuscan order were sought for in Vitruvius, who does not include it among the three canonic orders, but peripherally, in his discussion of the Etruscan temple (book iv, 7.2–3). Later Roman practice ignored the Tuscan order,[5] and so did Leon Battista Alberti in De re aedificatoria (shortly before 1452). Following Serlio's interpretation of Vitruvius (who gives no indication of the column's capital), in the Tuscan order the column had a simpler base—circular rather than squared as in the other orders, where Vitruvius was being followed—and with a simple torus and collar, and the column was unfluted, while both capital and entablature were without adornments. The modular proportion of the column was 1:7 in Vitruvius, and in Palladio's illustration for Daniele Barbaro's commentary on Vitruvius), in Vignola's Cinque ordini d'architettura (1562), and in Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura (1570).[6] Serlio alone gives a stockier proportion of 1:6.[7] A plain astragal or taenia ringed the column beneath its plain cap. Palladio agreed in essence with Serlio:

Unlike the other authors Palladio found Roman precedents, of which he named the arena of Verona and the Pula Arena, both of which, James Ackerman points out,[9] are arcuated buildings that did not present columns and entablatures. A striking feature is his rusticated frieze resting upon a perfectly plain entablature[10] Examples of the use of the order are the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome, by Baldassarre Peruzzi, 1532–1536, and the pronaos portico to Santa Maria della Pace added by Pietro da Cortona (1656–1667). Later spreadA relatively rare church in the Tuscan order is St Paul's, Covent Garden by Inigo Jones (1633). According to an often repeated story, recorded by Horace Walpole, Lord Bedford gave Jones a very low budget and asked him for a simple church "not much better than a barn", to which the architect replied "Then you shall have the handsomest barn in England".[11] Christ Church, Spitalfields in London (1714–29) by Nicholas Hawksmoor, uses it outside, and Corinthian within. In a typical usage, at the very grand Palladian house of Wentworth Woodhouse in Yorkshire, which is mainly Corinthian, the stable court of 1768 uses Tuscan. Another English house, West Wycombe Park, has a loggia facade in two storeys with Tuscan on the ground floor and Corinthian above. This recalls Palladio's Palazzo Chiericati, which uses Ionic over Doric. The Neue Wache is a Greek Revival guardhouse in Berlin, by Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1816). Though in most respects the Greek temple frontage is a careful exercise in revivalism, there are minimal plain bases to the thick fluted columns and, despite having metope reliefs and a large group of sculpture in the pediment, there are no triglyphs or guttae. Nonetheless, despite these "Tuscan" aspects, the overall impression is strongly Greek and it is rightly always described as "Doric". Tuscan is often used for doorways and other entrances where only a pair of columns are required, and using another order might seem pretentious. Because the Tuscan mode is easily worked up by a carpenter with a few planing tools, it became part of the vernacular Georgian style that lingered in places like New England and Ohio deep into the 19th century. In gardening, "carpenter's Doric" which is Tuscan, provides simple elegance to gate posts and fences in many traditional garden contexts. Gallery

See alsoNotes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Tuscanic order. |

![Baroque Solomonic Tuscan columns of the Monastery of San Francisco, Antigua, Guatemala, unknown architect, early 17th century[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/39/2010.05.13.173939_Iglesia_San_Francisco_Antigua_Guatemala.jpg/450px-2010.05.13.173939_Iglesia_San_Francisco_Antigua_Guatemala.jpg)

![Neoclassical Tuscan columns of the Hôtel du Châtelet (Rue de Grenelle no. 127), Paris, by Mathurin Cherpitel, 1776[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Paris_-_H%C3%B4tel_du_Ch%C3%A2telet_-_127_rue_de_Grenelle_-_001.jpg/450px-Paris_-_H%C3%B4tel_du_Ch%C3%A2telet_-_127_rue_de_Grenelle_-_001.jpg)

![Neoclassical Tuscan columns of the Chapelle expiatoire du Champ-des-Martyrs, Brech, France, by Auguste Caristie, 1824[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Morbihan_Auray_Champs_Martyrs_-_panoramio.jpg/400px-Morbihan_Auray_Champs_Martyrs_-_panoramio.jpg)

![Neoclassical Tuscan columns in the Neues Museum, Berlin, by Friedrich August Stüler, 1845–1850[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/Interior_of_the_Neues_Museum_%2813%29.jpg/174px-Interior_of_the_Neues_Museum_%2813%29.jpg)

![Neoclassical Tuscan columns of the Abingdon War Memorial, Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, by John George Timothy West, 1921[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/The_war_memorial_in_Abingdon_-_geograph.org.uk_-_4262210.jpg/215px-The_war_memorial_in_Abingdon_-_geograph.org.uk_-_4262210.jpg)