|

Whiskey Bottom Road

Whiskey Bottom Road is a historic road north of Laurel, Maryland that traverses Anne Arundel and Howard Counties[1] in an area that was first settled by English colonists in the mid-1600s. The road was named in the 1880s in association with one of its residents delivering whiskey after a prohibition vote. With increased residential development after World War II, it was designated a collector road in the 1960s; a community center and park are among the most recent roadside developments. 39°06′58″N 076°49′53″W / 39.11611°N 76.83139°W Route descriptionWhiskey Bottom Road runs through North Laurel, Maryland starting at the later Maryland Route 198 in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. The road continues westward across U.S. Route 1 and terminates at a dead end just prior to the I-95 and Route 216 interchange in Howard County, Maryland, which were built long after this historic road.

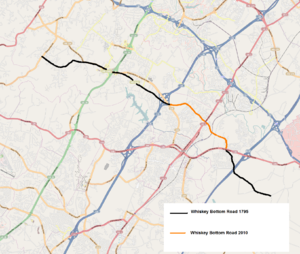

Martenet's 1860 Map of Howard County Maryland, and the 1861 Map of Prince George's County, Maryland, from the Library of Congress, clearly depict the original road. Approximately 60% of that original has been renamed after being bisected by I-95, then further divided by Maryland Route 198 and I-295. Starting from the northwest to the southeast:

Whiskey Bottom Road maintains its original historical path and name until meeting with Maryland route 198 in Anne Arundel County. The path continues to the southeast under several different names.

Intersections

HistoryOriginsThe North Laurel region has origins dating to 1650.[10] In a passage from the book The founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland, the author cites letters describing the conflict between the Native Americans and the new settlers of the area... In 1681, Robert Proctor, from his town on the Severn, Thomas Francis, from South River and Colonel Samuel Lane, from the same section, all wrote urgent letters stating that the Indians had killed and wounded both Negroes and English men "at a plantation of Major Welsh's," and "had attempted to enter the houses of Mr. Mareen Duvall and Richard Snowden."[11] The farms and their owners described are shown later as being along the original starting point of Whiskey Bottom Road. In the 1950s, inn owner Albert L. Dalton posted a sign along Route 1 which read "Historical Whiskey Bottom Road—Circa 1732 A.D."[12] The majority of the modern road falls within "Robinhood's Forest", a land grant between Laurel and Sandy Spring, Maryland that was part of the accumulated 10,500-acre (42 km2) Birmingham Manor estate of the Snowden family starting in 1669 with a 500-acre (2.0 km2) patent purchased in exchange for 1,100 lb (500 kg) of tobacco.[13] A 1795 map of Anne Arundel County by Dennis Griffith[14] shows the unnamed path that is now known as Whiskey Bottom Road starting at the Ridgley Farm in Highland, Maryland, passing south of Whites Mill in Savage, Maryland and terminating at the original Birmingham Manor site in South Laurel.[15] Martenet's 1861 Map of Prince George's County and 1860 Map of Howard County show the route in more detail. The Howard County – District 6, Guilford, Savage Factory, Annapolis Junction, Laurel City map published by G. M. Hopkins in 1878 referenced the dirt road as Old Annapolis Road, the expanded 1878 county map from the same publisher contradicted this name and listed it as Laurel Road.[16] The date when the road obtained its name is not well published. Its first newspaper mention was in 1892 as Whisky Bottom.[17] One resident who lived on the road since the 1890s explained that the road name came from the low point near the railroad tracks where trains would pick up wagon-delivered barrels of Maryland Rye whiskey from a distillery near the Laurel Mill.[18] Others have referenced the road as Sandy Bottom, and Rural Route No. 1.[19] The Howard County School Board used Whiskey Bottom as the name rather than alternatives in 1939.[20] Geographically, following the fall-line of the road, the "Bottom" of Whiskey Bottom would be the convergence of the Western and Southwestern Branches of the Patuxent River, where goods could be shipped to nearby Upper Marlboro, The Chesapeake Bay, or to Europe.[21] A large section of the original road is now called Scaggsville Road or Maryland Route 216. The 1600sMany roads of the region followed Native American footpaths, which themselves followed the most advantageous paths for travel over terrain. Despite the name, Whiskey Bottom follows the highest elevation between rivers to either side, making it the least prone path to flooding or muddy conditions. The path of the modern road very closely aligns with the fall line between the Patuxent River and its Northern branches. The fall line originates near modern New Carrollton to the convergence of the Southwest and Western branch of the Patuxent river near Crofton.[22] Prior to settlement by the English, the lands up and down the Patuxent river were occupied by various tribes of Algonquin speaking Native Americans. The Native American trails were not paved or marked, but were commonly cleared regularly of underbrush and saplings by controlled fires, creating wide corridors lined only with mature trees up to six feet in diameter.[23] In the 1620s The Susquehannocks pushed tribes out to the Southeast to reduce competition occupying the area as far south as the Potomac river.[24] The Susquehannocks were well armed hunters and profited from Beaver trading with the English. By 1632 Lord Baltimore claimed title to issue land grants in Maryland through Charles I of England. In 1652, the Susquehannocks treatied with Marylanders to keep trade flowing and receive arms to use against the Iroquois to the north.[25] By 1675, efforts were underway to eliminate the Susquehannocks from the region.[26] In 1666, Maryland issued its first road laws, with the path between Leonardtown to Port Tobacco as one of the earliest examples.[27]  In 1685 Lord Baltimore granted Richard Snowden Sr. 1,976 acres (8.00 km2) of land on the Patuxent river (Patented as Robinhood's Forest). The iron works would form the start of the road heading upriver to the northwest.[28] Snowden built Birmingham Manor at the site in 1690 at the terminus of the old post road and the start of Whiskey Bottom. It lasted until a fire on August 20, 1891. In 1686, the nearby Warfield's range was laid out. Overlook Farm was built on the site; its operators would later account that they would roll tobacco product down Whiskey Bottom Road in barrels toward the Patuxent for shipping.[29] In 1696, Maryland ordered the construction of four "Rolling Roads" to move tobacco to Annapolis in "hogshead" barrels that would be hand rolled, or later pulled by oxen via rope with an axle through the center. This account would have made Old Annapolis (Whiskey Bottom) one of these work roads.[30][31] The 1700sIn 1704, Maryland issued instructions to mark all trees along trails to Annapolis with a "AA" mark, and notches for paths that lead to a county seat or church.[32] In 1732, the Maryland Assembly voted to provide incentives to encourage the iron industry in Maryland. They enacted a law excluding iron workers from required road service. In 1750, this was modified to one in every ten iron laborers were required to perform road maintenance.[33] In 1736, roadside residents Richard Snowden III "Ironmaster" (1688–1763), Joseph Cowman, and three other partners founded "Patuxent Iron Work Company", Maryland's first ironworks.[34] The ironworks were built on the site of an even older forge that predated it by some time.[35] From the 1760s to the 1780s the ironworks were managed by Samuel, John and Thomas Snowden, employing a workforce of about 45 slaves.[36] The ironworks peaked with an annual output of 1200 tons. The owners dismantled the furnace in 1856 due to a lack of wood and ore. The 1800s  Most residents of Whiskey Bottom Road in this time were farmers. Typical crops that they would plant were butter beans and sugar corn, radishes, beets, eggplant, tobacco, and apple trees.[37] Slavery was in common practice among the farmers along the road until emancipation. Runaway slave ads were regularly placed by Whiskey Bottom residents in the Baltimore Sun newspaper.[38][39] In 1822, the Savage Manufacturing Company purchased 600 acres along the northwest corner of the crossroads with the Washington Turnpike to build the Savage Mill. 181 acres of mixed farm and forest that formed the crossroads with Whiskey Bottom and the Washington Turnpike were sold by the company to John Holland in 1841. The semi-formal stone house he bought still stands, with a Route 1 address due to subdivision.[40] In 1828, a survey was conducted to run a canal across the road to connect Elkridge to the proposed C&O Canal via Bladensburg.[41] Rather, the B&O was constructed. In 1834, fights broke out among rival Irish and German railroad workers.[42] The violence escalated in November when John Watson and William Messer were murdered at the construction site around Whiskey Bottom. Horace Capron and other militiamen gathered some 300 workers to be questioned for the murders. In January 1835, Owen Murphey was sentenced to death by hanging at the location of the murders. Patrick Gallagher and Terence Coyle were also sentenced to 18 years of hard labor.[43] In 1853, the State of Maryland put into law a requirement that all public roads be widened to at least 30 feet (9.1 m) between fences.[44] Born in Montgomery County, Gustavus Ober was a prominent Presbyterian Sunday School teacher at All Saint's church and owned several properties along Whiskey Bottom Road. The successful entrepreneur was married into, and partnered with, the Kettlewell family with residences on nearby Gorman road.[45] Together in 1856, they formed the successful Baltimore company G Ober and Sons, marketing "Kettlewell's Manipulated Guano". The company stopped production when the civil war cut off its customer base in the southern states.[46][47][48]  The Bacontown community along the Anne Arundel portion of Whiskey Bottom Road was established by the freed slave Maria Bacon. A road sign proclaims "Bacontown EST. 1860". Approximately 3 dozen small homes were established along with a church and schoolhouse. The community consists of multi-generational families who have worked together to drive out crime and prevent redevelopment of a community that looks much the same as it did in the 20th century. Bacontown was the last neighborhood along the road to link to city water and sewer service, in 1997.[49] The Mount Zion United Methodist Church and Bacontown Park are the most visible landmarks.[50] In 1862, during the Civil War, Brig.-Gen. John C. Robinson commanded troops guarding the B&O railroad. The First Michigan Regiment was assigned to the section crossing Whiskey Bottom Road.[51] United States postal mail started service to residents of "Whiskey Bottom Road" from the Laurel post office in 1899.[52] By 1874, Prince George's County disallowed gates across public roads. Prior to this law, it was common for roads running through large farms and plantations to gate the road rather than fence along either side. Riders would have to dismount, open and close each gate along the way.[53] The 1900sA 1-mile (1.6 km) dirt oval racetrack once operated in the early 20th century at the southeast corner of Whiskey Bottom and Brock Bridge Roads.[54] During prohibition, the road hosted speakeasies with houses outfitted with hidden rooms and liquor storage in the walls to hide supplies from stills along the Hammond Branch river (Patuxent).[18] The road became the link for communities such as Highland to the nearest train station in Laurel.[55] After the great depression, many family farms were sold to pay back taxes and were subdivided into lots for owner-built homes. Construction of these homes peaked after World War II. Shortly after city water was provided to the Howard county residents in the 1960s,[56] Whiskey Bottom Road was designated a collector road. The majority of home construction from that point on has been in the form of developments on subdivided property managed by homeowners associations. Only one house on the historic road is listed in Howard County's Historic property inventory: The Joseph Travers House, a Folk Victorian dwelling built on land called "Sappington's Sweep" in 1890 over the site of an earlier 1862 house.[57]  Between 1936 and 1940 the construction of the Patuxent Research Refuge displaced all residents along the southeast section of the road. The construction of I-295 cut off access to the road, and its remaining sections were renamed. The cut-off-road sections were used to train troops and tank operators during WWII, and were returned to the wildlife research center in 1991.[58]  After WWII, Israel Kroop operated Kroop's Goggles on Whiskey Bottom behind the racetrack. He developed innovative semi-disposable vented goggles that have become the standard for jockeys and skydivers. The business continued after Kroop's death in 1991; the family sold it in 2008, and its product remains locally produced in Savage, Maryland.[59] In 1959, the plans for construction of the I-95 highway that eventually bisected Whiskey Bottom Road were met with protests.[60] On the northwest corner of U.S. Route 1 and Whiskey Bottom Road, Crickett's California Inn hosted live bands from the 1960s until its relocation in 2008. The bar hosted various formats, switching to country in the 1990s and karaoke in the first decade of the 21st century.[61] The bar was previously known as Randy's California Inn, and The California Inn.  The Edy's Ice Cream plant on the northeast corner of U.S. Route 1 and Whiskey Bottom Road is the second-largest ice cream manufacturing facility in the world. A smaller plant was originally built by Clifford Y. Stephens at the site in 1961.[62] The factory packaged goods for High's Dairy Stores. In 1987 the facility was acquired by Southland and later by Nestle, which owns the Edy's and Dreyer's brands. In 2003 a $210 million expansion was built on land previously operated as Pfister's mobile home park. Seventy three families were moved out of the trailer park that had operated since World War II. Prior to that, the land was operated as a chicken farm.[63] The adjoining office complex once occupied by High's management is now the Phillip's School for Contemporary Education.[citation needed] In 1958, Melville W. Beardsley founded National Research Associates company and settled on Whiskey Bottom Road in 1961. NRA developed and tested over 30 air cushion vehicles, with the Air Gem Air cushion vehicle produced as their first product. NRA also sold Disney's Flying Saucers attraction under license. The Company went out of business in 1963.[64][65] In 1962, 47 acres (190,000 m2) were rezoned at the corner of Whiskey Bottom and All Saint's Road to form the Whiskey Bottom Apartments, the first development along the road.[66] The New MillenniumThe 2001 Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. tornado outbreak brought an F3 tornado on a direct path crossing Whiskey Bottom Road. The tornado lifted momentarily and set back down on the other side of the road. Nearby buildings just a few hundred feet North and South of the road showed significant tornado damage.[67]  In 2009, the primary entrance to the North Laurel Community Center was realigned to Whiskey Bottom Road. A 63,000 sq ft (5,900 m2) Leed Silver certified community center and park was built at the location and opened on June 3, 2011.[68][69] It features amenities similar to the Glenwood Community Center in Northern Howard County. The funding and takeover of the various undeveloped properties through eminent domain was a multi-decade effort. The project has been supported by local leaders and community groups, with some criticism over the environmental impact, effect on adjoining properties, and the safety of the road entrance.[70] Namesake distillery In 1899 a large monopoly, The Distilling Company of America, pooled $125 million to buy all the distilleries on the east coast, and consolidate the production to a few sites, effectively wiping out all large Maryland Rye Distilleries.[71] The path that is now Whiskey Bottom Road, would have included settlements, farms and plantations spanning from Davidsonville to Highland, any of which commonly produced whiskey in small quantities. One resident's recollection from the late 1800s noted the "Maryland Rye" distillery was near the Laurel Mill, which used wagons to get the product to "Whiskey Bottom".[18] In the 1879 book History of Tama County, Iowa, the author states that after a prohibition vote in April 1855, the residents drank the first barrel of pure whiskey delivered by a man named Rouse living on Whiskey Bottom Road. "The road was named from this circumstance".[72] The Iowa Meskwaki Reservation shares an area with the uncommon Whiskey Bottom name. The Maryland road was named about the same time, under similar circumstances, and a family named Rouse also played an influential role in the area. Due to unflattering connotations, the Meskwaki reservation eventually changed its Whiskey Bottom Road name to "Battlefield Road".[73] Road name controversyWhiskey Bottom or PatuxentLong-time residents associate the Whiskey Bottom name with a former whiskey distillery, a whiskey cart trail, and in later years with speakeasys and stills that were hosted in various farmhouses along the road.[74] For some, the perceived negative connotation of alcohol or alcoholism prompted attempts to hide, or change the road's name. Proponent W.R. Skeels took the connotation more seriously, declaring Whisky as the "Water of degradation and death".[18] Name change efforts were publicized as far away as Florida in an Ocala Star-Banner newspaper article from May 3, 1955, titled "Battle of Whiskey Bottom Road Rages".[12]

In the 1950s, a lawyer named W.O. Skeels petitioned a Maryland Congressman Steele to rename the street Patuxent Drive. Resident W.R. Shauck complained to the press that he was told by a realtor that he was on Old Annapolis Road when he purchased the land a decade earlier, and it had to be changed.[18] The change was passed without notice to the residents.[37] A 1950 Washington Post article proclaimed that the new Patuxent Drive was now "dignified".[75] In 1954 the matter was brought to the Maryland State Roads Commission.[76] Markers for Patuxent Drive were placed at US Route 1.[77] In the ensuing battle of county vs. state rights, Howard County sided with the name of Whiskey Bottom. Residents in this time would address their mail to both street names depending on their preference, but Patuxent Drive fell out of use over time. C.H. Lamparter, owner of "Randy's California Inn" noted that "The name was changed when nobody was even looking"..."When the petitions are finished going around, we will still be calling the road what we always have called it."[18] Whiskey and school In October 1962, the Laurel Planning and Redevelopment Corporation gave Howard County 27 acres of woodland to build the Whiskey Bottom Road Elementary School within a proposed high-density development seeking zoning approval. The name was chosen in a 1972 board meeting. There were concerns about the name from the first hearings, but board members believed the historical value outweighed any negative connotations.[78] The new "open layout" school opened in 1973. Although the property reached to Whiskey Bottom Road, the school entrance and address was on North Laurel Road. The name was later shortened to Whiskey Bottom Elementary School. In 1991 a student movement considered the name unsuitable due to associations with alcohol and being considered ranked at "The Bottom". The new name for the school was Laurel Woods Elementary due to its proximity to the largest remaining stand of woods in Laurel. The majority of these woods were cleared in 2010 for the North Laurel Community Center.[79][80][81] Whiskey or WhiskyThe road name has been spelled Whisky Bottom Road and more recently, Whiskey Bottom Road. Although both are valid spellings, the later name associates it with liquor distilled in America or Ireland rather than Canada, Japan or Wales.[82] Scaggsville or Rocky GorgeWestern sections of the original road ran past the farm of the Scaggs family, in Scaggsville, Maryland, and have the name Scaggsville Road. Just like Whiskey Bottom, the name Scaggsville was considered distasteful enough to warrant a name change by some in 2002, but did not have enough public support to proceed.[83] In 1899, the post office dropped rural service to Scaggsville's other name, "Hells Corner".[84] Whiskey themesThe name "Whiskey Bottom Road" has inspired adjoining roads, schools, developments and businesses to adopt the whiskey theme or the entire name. The region is better known for producing a rye based Whiskey, "Maryland Rye",[85] but that name has not been adopted in the neighborhoods. Nearby Bourbon street is based on another whiskey variation, Bourbon, that has a corn base. A partial list of local items that have adopted the theme:

Although most of the Whiskey Bottom Road neighborhoods consist of single family homes fronting the street, the various developments of Canterbury Riding, The Seasons Apartments and Whiskey Bottom Town homes, form a well defined neighborhood frequently called Whiskey Bottom or the "Whiskey Bottom Area". Traffic control  The heavily traveled Baltimore-Washington corridors that Whiskey Bottom Road crosses have been the site of fatal accidents since automobiles were introduced.[88] The introduction of traffic lights improved safety, but increasing volume of traffic has kept the intersections on many "Most Dangerous" lists.[89] The B&O Railroad crossing also was a frequent historical source of accidents with carts and pedestrians. A steep curving bridge was first built over the railroad tracks reducing train collisions, but occasionally creating its own hazardous driving conditions. In 1990, a long-standing home pottery business was removed to regrade a modern bridge over the railroad. Pedestrians still travel along the tracks despite the improvements, with occasional deaths in the same place.[90][91] In 1950 Whiskey Bottom Road was straightened, widened, and Macadamized. By the end of the 20th century, the amount of transient traffic as well as local traffic from developments reached the point where residents of the street facing homes could not safely turn into and out of their driveways. The occasional auto accidents where vehicles struck houses[92][93] became commonplace. Traffic surveys concluded that the majority of accidents were from vehicles striking turning vehicles from behind. The traffic engineering departments of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties took two different approaches to the issue. In 1993 the Anne Arundel section adopted a road widening approach, taking eminent domain of properties and adding a shared center left-hand turn lane down the middle of the road. This was partially funded by the pending Russett development as a condition of zoning approval.[94] Howard County planned to follow suit in 2002 but opted to explore traffic calming after 98% of roadside residents petitioned against widening the road. A series of narrow choking islands, and roundabouts were placed along the roadway with the intention of physically restricting the maximum speed of a vehicle to the 30 mph (48 km/h) limit. Transient drivers have objected to the obstacles. Howard County engineers defend their usefulness in controlling reckless driving without the need for increased traffic patrols.[95][96] Howard County Project J4229 plans to modify Whiskey Bottom Road from U.S. Route 1 to the Anne Arundel County Line in 2011 to prepare for future BRAC-related development traffic.[97] DevelopmentThe population of residents along the road has increased substantially. In 1939 the number of roadside houses totaled nine. By 1950, only 30 families lived along the road.[18]  Adjacent developed properties include:

In 1994, an effort to redevelop land occupied by the Laurel Racetrack and its adjacent properties would have placed a new Washington Redskins Stadium at the crossroads of Whiskey Bottom Road and Brock Bridge Road. Citizens and clergy launched a successful effort that killed the proposal. A lack of sufficient parking space was a significant factor in the decision.[101] CrimeCrime along Whiskey Bottom Road is on par with the region and times. Newsworthy crime incidents provide a historical context of this quiet rural road's transition to a dense suburban thoroughfare. One of the first recorded incidents occurred on the road itself. On July 6, 1892, Rebecca Cager (Hensin) was found shot in the head by Dr. Hunt alongside "Whisky Bottom Road".[102][103] The earliest mention of carjacking occurred in 1959 with the abduction of two separate women at gunpoint ending at Whiskey Bottom Road.[104] The community of Bacontown was targeted for cross burnings in the 1950s followed by drug dealing issues in the 1980s. Lifelong residents Audrey Garnett and Lenore Carter worked with the community to drive out crime.[105] Occasionally a body is still found along the road.[106][107] The busy intersections of Whiskey Bottom Road with US Route 1 and Maryland 198 have a decades long history of prostitution.[108] Over the years police have made efforts to reduce the problem, but it persists to present times. One-day prostitution stings are held several times a year with 16–40 arrests a day.[109][110][111][112] In 2013, A string of arson attacks occurred up and down the wooded areas of the Patuxent river valley in Laurel. The Fieldstone development, and the historic Duvall Farm were burned from large brush fires.[113] In fictionIn the 2006 fiction book, Borrow Trouble by Mary Monroe and Victor McGlothin, the character Franchetta wound up in a small tick on the map called "Whiskey Bottom, Maryland" at the age of 18 hawking boxes of popcorn.[114] In musicA local Blues Band in Portsmouth, Hampshire, United Kingdom took up the moniker "Whiskey Bottom Road".[115][116] The Hitman Blues Band published a song named Whiskey Bottom Road in 1999 on their debut album "Blooztown" about being down and out.[117]

Notes

|