|

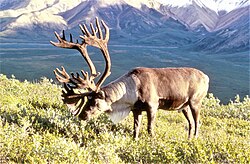

Wildlife of AlaskaThe wildlife of Alaska is both diverse and abundant. The Alaskan Peninsula provides an important habitat for fish, mammals, reptiles, and birds. At the top of the food chain are the bears. Alaska contains about 70% of the total North American brown bear population and the majority of the grizzly bears, as well as black bears and Kodiak bears. In winter, polar bears can be found in the Kuskokwim Delta, St. Matthew Island, and at the southernmost portion of St. Lawrence Island. Other major mammals include moose and caribou, bison, wolves and wolverines, foxes, otters and beavers. Fish species are extensive, including: salmon, graylings, char, rainbow and lake trout, northern pike, halibut, pollock, and burbot. The bird population consists of hundreds of species, including: bald eagles, owls, falcons, ravens, ducks, geese, swans, and the passerines. Sea lions, seals, sea otters, and migratory whales are often found close to shore and in offshore waters. The Alaskan waters are home to two species of turtles, the leatherback sea turtle and the green sea turtle. Alaska has two species of frogs, the Columbia spotted frog and wood frog, plus two introduced species, the Pacific tree frog and the red-legged frog.[1] The only species of toad in Alaska is the western toad. There are over 3,000 recorded species of marine macroinvertebrates inhabiting the marine waters, the most common being the various species of shrimp, crab, lobster, and sponge. MammalsBrown bear Alaska contains about 98% of the U.S. brown bear population and 70% of the total North American population.[2] An estimated 30,000 brown bears live in Alaska.[3] Of that number, about 1,450 are harvested by hunters yearly.[4] Brown bears can be found throughout the state, with the minor exceptions of the islands west of Unimak in the Aleutians, the islands south of Frederick Sound in southeast Alaska, and the islands in the Bering Sea.[2] The brown bear is the top predator in Alaska. The density of brown bear populations in Alaska varies according to the availability of food, and in some places is as high as one bear per square mile.[2] Alaska's McNeil River Falls has one of the largest brown bear population densities in the state.[2] Brown bears can be dangerous if they are not treated with respect. Between the years 1998 and 2002, there were an average of 14.6 brown bear attacks per year in the state.[5] Brown bears are most dangerous when they have just made a fresh kill, and when a sow has cubs.[2][6] Grizzly bearsAlaska also contains a majority of the grizzly bear population, both U.S. and total North American population (the grizzly bear is a subspecies of brown bear found throughout North America). Kodiak bearsKodiak Island is home to Kodiak bears, another subspecies that is the largest type of brown bear in the world.[2] Black bear The black bear is much smaller than the brown bear. They are found in larger numbers on the mainland of Alaska, but are not found on the islands off of the Gulf of Alaska and the Seward Peninsula.[7] Black bears have been seen in Alaska in a few different shades of colors such as black, brown, cinnamon, and even a rare blue shade.[8] They are widely scattered over Alaska, and pose more of a problem to humans because they come in close contact with them on a regular basis. They are considered a nuisance because they frequently stroll through local towns, camps, backyards, and streets because of their curiosity and easy food sources such as garbage.[8] While black bear attacks are exceedingly rare, they can pose a risk to public safety when food conditioned and habituated to humans due to an availability of human food sources. As many as 100,000 black bears live in Alaska.[9] Polar bear Alaska's polar bear populations are concentrated along its Arctic coastlines. In the winter, they are most common in the Kuskokwim Delta, St. Matthew Island, and at the southernmost portion of St. Lawrence Island. During the summer months, they migrate to the coastlines of the Arctic Ocean and the Chukchi Sea.[10] There are two main polar bear populations in Alaska. The Chukchi population is found off in the western part of Alaska near the Wrangell Islands, and the Beaufort Sea population is located near Alaska's North Slope.[10] Until the late 1940s, polar bears were hunted almost exclusively for subsistence by Inupiats and dogs teams, though from the late 1940s until 1972, sport hunting by others took place.[10] The 1958 Statehood Act set up a program for polar bear management, and further conservation efforts, including the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, have limited polar bear hunts.[10] Polar bear populations may be threatened by oil development and global warming.[10][11] Only about 4700 polar bears are known to inhabit Alaska.[12] Grizzly-polar bear hybridDue to climate change it has become more common to see more interbreed hybrids. Often called pizzly or grolar bears, these hybrid bears are rare. The ranges of both grizzlies and polar overlap one other.[13][14][15] Caribou Alaska is home to the caribou subspecies Rangifer tarandus granti.[16] While other parts of the world use the terms "caribou" and "reindeer" synonymously, in Alaska "reindeer" refers exclusively to domesticated caribou.[16] Caribou in Alaska generally are found in tundra and mountain regions, where there are few trees. However, many herds spend the winter months in the boreal forest areas.[16] Caribou are large-scale migratory animals and have been known to travel up to 50 miles (80 km) a day. The migratory activities of caribou are usually driven by weather conditions and food availability.[16] Changes in caribou migration can be problematic for Alaska Natives, who depend on caribou for food.[16] Caribou in Alaska are abundant; currently there are an estimated 950,000 in the state.[16] The populations of caribou are controlled by predators and hunters (who shoot about 22,000 caribou a year).[16] Though in the 1970s there were worries that oil drilling and development in Alaska would harm caribou populations, they seem to have adapted to the presence of humans, and so far there have been few adverse effects.[16] Moose The Alaskan subspecies of moose (Alces alces gigas) is the largest in the world; adult males weigh 1,200 to 1,600 pounds (542–725 kg), and adult females weigh 800 to 1,300 pounds (364–591 kg)[17] Alaska's substantial moose population is controlled by predators such as bears and wolves, which prey mainly on vulnerable calves, as well as by hunters.[17] Because of the abundance of moose in Alaska, moose-human interactions are frequent. Moose have played an important role in the state's history; professional hunters once supplied moose meat to feed mining camps. Athabascan people have hunted them to provide food as well as supplies for clothing and tools.[17] They are now hunted frequently by big game hunters, who take 6,000 to 8,000 moose per year.[17] Today, moose are often seen feeding and grazing along the state's highways. Moose can sometimes cause problems, as when they eat crops, stand in the middle of airfields, or dangerously cross the path of cars and trains. Moose are also a very popular icon in Alaska. Mountain goatMountain goats are found in the rough and rocky mountain regions of Alaska, throughout the southeastern Panhandle and along the Coastal Mountains of the Cook Inlet.[18] Populations are generally confined in the areas of the Chugach and Wrangell Mountains. Mountain goats have been transplanted to the islands of Baranof and Kodiak, where they have maintained a steady population.[18] The mountain goat is the only representation in North America of the goat-like ungulates.[18] Very little was known about mountain goats up until 1900.[18] They constantly migrate to different areas from the alpine ridges in the summer, and to the tree-line in the winter. BisonThe ancestors of the American bison (Bison bison) now in Alaska were transplanted from Montana in 1928, when 20 animals were imported by the Alaska Game Commission and released in the area of what is now Delta Junction. Additional herds have developed along the Copper River, Chitina River, and near Farewell from natural emigration and transplant. Small domesticated herds have also been established near Kodiak and Delta Junction, as well as on Popov Island.[19] Another subspecies of bison, the wood bison (b. b. athabascae) was once Alaska's most common large land mammal. The combined effects of pre-contact habitat change and human harvest were probably responsible for their disappearance. The last reported sighting of wood bison in Alaska was in the early 1900s. Oral history accounts from Alaska Native elders suggest that these bison were a resource for indigenous peoples in Alaska as recently as 200 years ago.[20] In 2003, there were approximately 900 wild American bison in Alaska.[21] Their numbers are controlled by managed sport hunting, as predation is not common. Bison can occasionally be seen on their summer range from the Richardson Highway south of Delta Junction, on the Delta Junction Bison range and on the Delta Agricultural Project. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game is currently reviewing plans to reintroduce wood bison to Alaska from Canada. Dall sheep Dall sheep live, rest, and feed in the mountain regions of Alaska where there is rocky terrain and steep, inclined land,[22] and are seen below their usual high elevation only when food is scarce. In their rocky environment, they are able to avoid predators and human activities. Alaska contains a good size population of Dall sheep, and are commonly sighted in the eastern and western sides of Denali National Park.[23] The most commonly known name for the male Dall sheep is a "ram" and they are distinguishable from the female Dall sheep, the ewe, by their thicker and more massive curling horns. The curling of the horns on a male Dall sheep correlate with age, and reach their full circular potential in seven to eight years.[24] Orca The orca is also known as the killer whale, despite the term receiving controversy over the fact that orcas are part of the dolphin family. The name comes from the way in which orcas hunt in large groups. The hunting style has often been compared to that of wolves. Another reason is their tendencies to eat other whales and large prey animals such as seals and sea lions.[25] Orcas in Alaska are notable for their size; the adult female orca can reach the length of twenty-three feet (7.0 m) whilst the adult male orca can reach up to twenty-seven feet (8.2 m).[26] Orcas are scattered among the Continental Shelf from southeast Alaska through the Aleutian Islands. They can also be seen in the waters of Prince William Sound.[25] Birds Hundreds of bird species inhabit Alaska, especially in coastal regions. Some of the more notable birds in Alaska include: ReptilesTurtlesAlaskan waters are home to two species of turtles, the leatherback sea turtle and the green sea turtle.[27] Leatherback sea turtleLeatherback sea turtles often inhabit open waters but are still sometimes seen on coastal waters because of their title of the most migratory sea turtle species. It is the largest turtle in the world, weighing up to two thousand pounds and reaching up to six and a half feet by their adult years. The shell of the leatherback turtle, also called a carapace, can develop to one and a half inches and is the only shell on a sea turtle that is not hard and boney but rather soft and leather like to the touch. The front flippers on the leatherback turtle are not equipped with scales and claws unlike other species, and they outgrow the flippers on other species of sea turtles.[28] Green sea turtleThe green sea turtle is named after its distinct green skin color, contrary to the idea that the green comes from their shell, which is typically brown or a dark olive. This turtle is capable of gaining up to 700 pounds and growing up to 5 feet. Most of these turtles live in coastal waters near Europe and North America. The male green sea turtle is larger in size than the female, and they also have longer tails. Both turtles have paddle shaped flippers that they use to burrow in sand and lay their eggs. One Green Sea Turtle can have up to 200 eggs.[29] AmphibiansFrogsAlaska has two species of frogs. They are the Columbia spotted frog and wood frog. Alaska also is inhabited by two introduced frog species, the Pacific tree frog (also referenced as the Pacific chorus frog), and the red-legged frog.[1] The only species of toad in Alaska is the western toad.[30] Pacific chorus frogThe Pacific chorus frog's name derives from their auditory performance in their mating call. The two-note male can signal a mating call via the two large and round vocal sacs that inflate beneath the chin repeatedly, sounding like a chorus. The Pacific chorus frog itself is visually identified as a frog reaching up to two inches long with a black stripe extending from the nose tip to shoulder, whose color changes with the temperature and humidity.[31] Red-legged tree frogThe red-legged tree frog can grow past five inches given their long hind legs and elongated abdomen. The body is translucent red. This species of tree frogs live in wet environments such as wetlands and moist forest and typically breed in well shaded streams and rivers.[32] Columbia spotted frogThe Columbia spotted frog is typically dark brown, grey, or green and has spots on its back and sides. It lives in aquatic environments such as lakes, rivers, ponds, and marshes. They typically breed in aquatic areas such as still rivers and breed between 200 and 500 eggs at a time.[33] Wood frogThe wood frog is a light brown frog with dark patches over its eyes and extending down its back. These palm size frogs typically grow up to 3 inches. The Wood Frog is notorious for its verbal spring calling to attract other frogs, which is short and harsh. This frog gets its name from its habitat choice, which consists of heavily forested areas containing rocks, trees, and more. The Wood Frog however, breeds in wetlands and can breed up to 3,000 eggs at a time.[34] Western toadThe western toad is a large toad that has small circular or oval shaped warts down its back. This toad is often green or brown and have dark parotoid glands above the eyes. The eyes on the western toad are horizontal, unlike other toads who have vertical pupils. Western toads inhabit low elevation aquatic areas like wetlands, lake shores, wet meadows, marshes, and beaver ponds.[35] SalamandersAlaska is also home to three species of salamanders; they are the northwestern salamander, long-toed salamander, and rough-skinned newt. Northwestern salamanderAmbystoma gracile, the northwestern salamander, is a dark brown salamander reaching up to 23 centimeters long with dark protruding eyes and a visible parotoid glands. This salamander can be poisonous to its predators because of the excretion of a white poison through its glands when threatened. The northwestern salamander inhabits both forest and water bodies, but has a proclivity to live in burrows in the forest. The salamander also chooses to live under rocks, debris, and trees in the forest environment.[36] Long-toed salamanderAmbystoma macrodactylum, the long-toed salamander, is a salamander that occupies widespread regions, including the coastal regions of the pacific northwest. Long-toed salamanders live in a variety of habitats including sagebrush communities, coniferous forest, and in alpine meadows. Eggs and larvae have been spotted in watery areas including lakes, ponds, wetlands, springs, and puddles. An adult salamander can grow between 5 centimeters and 8.1 centimeters and are typically black with multicolored dorsal stripes and white speckling on their sides. This salamander has a long hind toe, which is where the name is derived from.[37] Rough-skinned newtTaricha granulosa, the rough-skinned newt, is a salamander.[38] This newt is multicolored, typically light brown on the back and yellow bellied, but can sometimes be olive green on the back. The rough-skinned newt is capable of growing up to 26.1 centimeters and will typically reach at least 12.7 centimeters. The newt's name comes from the granular and rough texture on their skin. The skin on the newt is toxic and releases a powerful neurotoxin called Tetrodotoxin, which can effect mucous glands and skin. FishAlaska has quite a variety of fish species. Its lakes, rivers, and oceans are home to fish, some including trout, salmon, char, grayling, halibut, lampreys, lingcod, longnose sucker, pacific herring, black rockfish, salmon shark, sculpin, walleye pollock, white sturgeon, and various forms of whitefish.[39] Salmon Alaska is home to five species of salmon: The chum salmon, which is banded green, yellow, and purple with a white tip on the anal fin, sockeye salmon, a deep red salmon with a white mouth, coho salmon, a maroon salmon with black spots, the Chinook salmon, also called the "king salmon", has a black gum line and black mouth and the pink salmon, which can be distinguished by its small size and overall pink hue.[40] Every year, the salmon participate in the great spawning migration up against the river currents. They do this in large numbers and are frequently seen jumping out of the water. This is a physical effort of them trying to go against the current. Bears, particularly brown bears, take advantage of this event by swarming to the rivers, and indulging in the salmon feast. Bear Lake, near Seward on the Kenai Peninsula, has been the site of salmon enhancement activities since 1962. Rainbow troutThe most common types of rainbow trout that lives in Alaska are the stream-resident and the steelhead. The rainbow trout lives most of its life in freshwater and migrates into estuaries upon maturation.[41] The largest rainbow trout caught weighed close to 15 pounds and was 19 inches in lengths. Rainbow trout live in streams and are native to the North Pacific Ocean. CharArctic char in Alaska are closely related to both trout and salmon, but are heartier and can live in harsher conditions such as colder and deeper northern water. The Arctic char can weigh up to 20 pounds.[42] GraylingThe grayling, inhabit mountain lakes and still rivers.[43] The grayling has a long dorsal fin that is multicolored, typically consisting of reds and aquas.[44] HalibutThe Pacific halibut is the largest flatfish in the family Pleuronectidae. The halibut swims sideways due to its lateral flattening, and most adults have both eyes on their upward-facing side. The scales on the halibut are embedded into the skin, giving the illusion that the halibut is smooth.[45] LampreyThe lamprey is an eel-like jawless vertebrate that is a part of the family Petromyzonidae. Lampreys are freshwater fish often found around coastal waters and burrow their larvae in such waters.[46] LingcodThe lingcod is a bottom feeder and are commercially harvested. It is a large fish that can grow up to 5 feet and weigh up to 80 pounds by their maturation stage. Colors range from brown, grey, green, blue, and pink, and they have dark and light spotting. The lingcod thrives in the depths of the ocean floor and are found in coastal regions around Alaska and in the Bering Strait.[47] Longnose suckerThe longnose sucker is the sucker fish with the greatest statewide distribution. It can weigh up to 5 pounds and lives in cold water streams. The sides, head, and top of the longnose sucker range from dark green to slate black while the belly is often white or yellow.[48] Pacific herringThe Pacific herring does not have any distinct markings, but are rather sleek and silver with a bluish green tint. Its scales on its underside create a slightly serrated effect. The Pacific herring is capable of growing up to 18 inches, but rarely grow past 9 inches.[49] Black rockfishThe black rockfish is a blackish grey fish with a large mouth, spinous dorsal fin, and dark stripes for its eyes to its gills. This fish can weigh up to 11 pounds and grow up to 27.6 inches by the time they reach adulthood.[50] Salmon sharkThe salmon shark is a shark that can grow up to 10 feet. This shark is light grey with a white tail. The male salmon shark matures between 9–10 years while the female shark matures at around 10–11 years.[51] SculpinSculpin are small, fresh or saltwater fish that rarely grow any longer than 7 inches. Their habitats range form headwater streams to slow and rocky streams to coastal saltwater areas. The sculpin are flattened and have wide fins to help them secure themselves to the bottom of water bodies in harsh conditions.[52] Walleye pollockThe walleye pollack is a key species to Alaska's fisheries. The pollack is a cod, and is multicolored, ranging from brown, green, silver, and white. The walleye pollack can grow up to 3 and a half feet and weight up to 13.3 pounds and is also called the fake Walleye.[53][54] White sturgeonThe white sturgeon is different from other fish because they do not have scales, but rather boney plates extending from its gill to tail called scutes instead. The white sturgeon is considered a bottom-feeder and rummages the sea floor for food. This fish is toothless and ingests through means of suction, and has tastebuds on the outside of its mouth.[55] Marine macroinvertebratesAlaska has 3,708 recorded species of marine macroinvertebrates inhabiting the marine waters from the intertidal zone, the continental shelf, and upper continental slope to abyssal depths, from the Beaufort Sea at the Arctic border with Yukon, Canada; the eastern Chukchi Sea, the eastern Bering Sea, the Aleutian Islands to the western border with Russia; and the Gulf of Alaska to Dixon Entrance at the southern border with British Columbia.[56] Among the more commonly encountered are various species of shrimp, crab, lobster, and sponge. Endangered speciesAlaska has one of the smallest endangered species lists of U.S. states. According to the Alaska Department of Fish & Game there are only 12 endangered species, nearly all marine. They are: Extinct speciesSeveral local species have become extinct since Europeans reached the region. They include:[57] See alsoReferences

|