|

Winnie-the-Pooh (book)

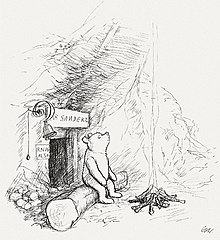

Winnie-the-Pooh is a 1926 children's book by English author A. A. Milne and English illustrator E. H. Shepard. The book is set in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood, with a collection of short stories following the adventures of an anthropomorphic teddy bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, and his friends Christopher Robin, Piglet, Eeyore, Owl, Rabbit, Kanga, and Roo. It is the first of two story collections by Milne about Winnie-the-Pooh, the second being The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Milne and Shepard collaborated previously for English humour magazine Punch, and in 1924 created When We Were Very Young, a poetry collection. Among the characters in the poetry book was a teddy bear Shepard modelled after his son's toy. Following this, Shepard encouraged Milne to write about his son Christopher Robin Milne's toys, and so they became the inspiration for the characters in Winnie-the-Pooh. The book was published on 14 October 1926, and was both well-received by critics and a commercial success, selling 150,000 copies before the end of the year. Critical analysis of the book has held that it represents a rural Arcadia, separated from real-world issues or problems, and is without purposeful subtext. More recently, criticism has been levelled at the lack of positive female characters (i.e. that the only female character, Kanga, is depicted as a bad mother). Winnie-the-Pooh has been translated into over fifty languages; a 1958 Latin translation, Winnie ille Pu, was the first foreign-language book to be featured on the New York Times Best Seller List, and the only book in Latin ever to have been featured. The stories and characters in the book have been adapted in other media, most notably into a franchise by The Walt Disney Company, beginning with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, released on 4 February 1966 as a double feature with The Ugly Dachshund. It remains protected under copyright in other countries, including the UK. Background and publicationBefore writing Winnie-the-Pooh, A. A. Milne was already a successful writer. He wrote for English humour magazine Punch, had published a mystery novel, The Red House Mystery (1922), and was a playwright.[1] Milne began writing poetry for children after being asked by fellow Punch contributor, Rose Fyleman.[2] Milne compiled his first verses for publishing, and though his publishers were initially hesitant to publish children's poetry, the poetry collection When We Were Very Young (1924) was a success.[1] The illustrations were done by artist and fellow Punch staff E. H. Shepard.[1]  Among the characters in When We Were Very Young was a teddy bear that Shepard modelled after one belonging to his son.[1] With the book's success, Shepard encouraged Milne to write stories about Milne's young son, Christopher Robin Milne, and his stuffed toys.[1] Among Christopher's toys was a teddy bear he called "Winnie-the-Pooh". Christopher got the name "Winnie" from a bear at the London Zoo, Winnipeg. "Pooh" was the name of a swan in When We Were Very Young.[1] Milne used Christopher and his toys as inspiration for a series of short stories, which were compiled and published as Winnie-the-Pooh. The model for Pooh remained the bear belonging to Shepard's son.[1] Winnie-the-Pooh was published on 14 October 1926 by Methuen & Co. in England and E. P. Dutton in the United States.[1] As a work first published in 1926, the book entered the public domain in the United States on 1 January 2022. British copyright of the text expires on 1 January 2027 (70 calendar years after Milne's death) while British copyright of the illustrations expires on 1 January 2047 (70 calendar years after Shepard's death). Stories  Some of the stories in Winnie-the-Pooh were adapted by Milne from previous published writings in Punch, St. Nicholas Magazine, Vanity Fair and other periodicals.[3] The first chapter, for instance, was adapted from "The Wrong Sort of Bees", a story published in the London Evening News in its issue for Christmas Eve 1925.[4] Classics scholar Ross Kilpatrick contended in 1998 that Milne adapted the first chapter from "Teddy Bear's Bee Tree", published in 1912 in Babes in the Woods by Charles G. D. Roberts.[5][6] The stories in the book can be read independently. The plots do not carry over between stories (with the exception of Stories 9 and 10).

ReceptionThe book was a critical and commercial success; Dutton sold 150,000 copies before the end of the year.[1] First editions of Winnie-the-Pooh were published in low numbers. Methuen & Co. published 100 copies in large size, signed and numbered. E. P. Dutton issued 500 copies of which only 100 were signed by Milne.[2] The book is Milne's best-selling work;[7] the author and literary critic John Rowe Townsend described Winnie-the-Pooh and its sequel The House at Pooh Corner as "the spectacular British success of the 1920s" and praised its light, readable prose.[8] Contemporary reviews of the book were generally positive. A review in The Elementary English Review reviewed the book positively, describing it as containing "delightful nonsense" and "unbelievably funny" illustrations.[9] In 2003, Winnie the Pooh was listed at number 7 on the BBC's survey The Big Read, a survey of the British public to determine their favourite books.[10] In 2012 it was ranked number 26 on a list of the top 100 children's novels published by School Library Journal.[11] AnalysisTownsend describes Milne's Pooh works as being "as totally without hidden significance as anything written." In 1963 Frederick Crews published The Pooh Perplex, a satire of literary criticism that contains essays by fake authors on Winnie-the-Pooh.[8] The book is introduced as trying to make sense of "one of the greatest books ever written" on the meaning of which "nobody can quite agree".[12] Crews' book had a chilling effect on any substantive analysis of the book, particularly for the ten years following its publication.[13] Although Winnie-the-Pooh was published shortly after the end of the First World War, it takes place in a isolated world free from major issues, which scholar Paula T. Connolly describes as "largely Edenic" and later as an Arcadia standing in stark contrast to the world in which the book was created. She goes on to describe the book as nostalgic for a "rural and innocent world". The book was published towards the end of an era when writing fantasy works for children was very popular, sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Children's Literature.[14] In Alison Lurie's 1990 essay on Winnie-the-Pooh, she argues that its popularity, despite its simplicity, comes from its "universal appeal" to people who find themselves at a "social disadvantage," and gives kids as one obvious example of this. The power and wise status that Christopher Robin receives, she claims, also appeals to children. Lurie draws a parallel from the setting of an environment that feels small and is devoid of aggression, with most of the activities involving exploring, to Milne's childhood, which he spent at a small suburban same-sex school. In addition, the rural backdrop without cars and roads is similar to his life as a child in Essex and Kent, before the start of the 20th century. She argues that the characters have widespread appeal because they draw from Milne's own life, and contain common feelings and personalities found in childhood, such as gloominess (Eeyore) and shyness (Piglet).[13] In Carol Stranger's feminist analysis of the book, she criticises this idea, arguing that, since every character other than Kanga is male, Lurie must believe that the "male experience is universal." The main critique, however, that Stranger levels is that Kanga, the only female character and the mother of Roo, is consistently made out as negative and a bad mother, citing a passage in which Kanga mistakes Piglet for Roo and threatens to put soap in his mouth if he resists taking a cold bath. This, she claims, forces female readers either to identify themselves with Kanga, and "call up the dependency, the pain, vulnerability and disappointment" many babies feel towards their caregivers, or to identify with the male characters, and see Kanga as cruel. She also notes that Christopher Robin's mother is mentioned only in the dedication.[15] TranslationsThe work has been translated into 72 languages,[16] including Afrikaans, Czech, Finnish and Yiddish.[1] The Latin translation by the Hungarian Lénárd Sándor (Alexander Lenard), Winnie ille Pu, was first published in 1958, and, in 1960, became the first foreign-language book to be featured on the New York Times Best Seller List, and the only book in Latin ever to have been featured therein.[17] It was also translated into Esperanto in 1972, by Ivy Kellerman Reed and Ralph A. Lewin, Winnie-La-Pu.[18] The work was featured in the iBooks app for Apple's iOS as the "starter" book for the app. Winnie-the-Pooh also received two Polish translations, which vastly differed in their interpretation of the work. Irena Tuwim published the first translation of the work in 1938, titled Kubuś Puchatek. This version prioritized adopting Polish language and culture over a direct translation, which was well received by readers.[19] The second translation, titled Fredzia Phi-Phi, was published by Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska in 1986. Adamczyk-Garbowska's version was more faithful to the original text, but was widely criticized by Polish readers and scholars, including Robert Stiller and Stanisław Lem.[19] Lem harshly described Tuwim's easy-to-read translation as being "castrated" by Adamczyk-Garbowska.[19] The titular character's new Polish name, Fredzia Phi-Phi, also drew criticism from readers who assumed Adamczyk-Garbowska had changed Pooh's gender by using a female name.[20][21][22] Many of the new character names were also seen as being overly complicated compared to Tuwim's version.[19] Adamczyk-Garbowska defended her translation, stating that she simply wanted to convey Milne's linguistic subtleties that were not present in the first translation.[20] Legacy In 2018, five works of original art from the book sold for £917,500, including a map of the Hundred Acre Wood that sold for £430,000 and set a record for the most expensive book illustration.[23] SequelsMilne and Shepard authoredMilne and Shepard went on to collaborate on two more books: Now We Are Six (1927) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928).[1] Now We Are Six is a poetry volume like When We Were Very Young, and includes some poetry about Winnie-the-Pooh. The House at Pooh Corner is a second volume of stories about Pooh, and introduces the character Tigger.[1] Milne never wrote another Pooh book, and died in 1956. Penguin Books has called When We Were Very Young, Winnie-the-Pooh, Now We Are Six, and The House At Pooh Corner "the basis of the entire Pooh canon."[1] AuthorizedThe first authorized Pooh book after Milne's death was Return to the Hundred Acre Wood in 2009, by David Benedictus. It was written with the full backing of Milne's estate, which took the trustees ten years to agree to.[24] In the story, a new character, Lottie the Otter, is introduced.[25] The illustrations are by Mark Burgess.[26] The next authorized sequel, The Best Bear in All The World, was published in 2016 by Egmont.[27] It was written by Paul Bright, Jeanne Willis, Kate Saunders and Brian Sibley with illustrations again by Mark Burgess. The four authors each wrote a short story about one of the seasons: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall.[28][29] AdaptationsFollowing The Walt Disney Company's licensing of certain rights to Pooh from Stephen Slesinger and the A. A. Milne Estate in the 1960s, the Milne storylines were used by Disney in its cartoon featurette Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree.[30] The "look" of Pooh was adapted by Disney from Stephen Slesinger's distinctive American Pooh with his famous red shirt that had been created and used in commerce by Slesinger since the 1930s.[31] Parts of the book were adapted to three Russian-language short animated films directed by Fyodor Khitruk: Winnie-the-Pooh (based on chapter 1), Winnie-the-Pooh Pays a Visit (based on chapter 2), and Winnie-the-Pooh and a Busy Day (based on chapters 4 and 6).[32] In 2022, Jagged Edge Productions announced that a horror film starring the character was put in production, and was released on February 15, 2023.[33] This production became possible after the book became public domain in the United States.[34] A sequel was released in 2024. Passage into the public domainWinnie-the-Pooh's entrance into the public domain in the United States on January 1, 2022 was noted by several news publications, generally in the context of a greater Public Domain Day article.[35][36][37][38] The book entered the public domain in Canada in 2007.[39][40][41] The UK copyright will expire at the end of 2026, the 70th year since Milne's death. As Shepard lived until 1976, the UK copyright on his illustrations will remain in effect until 2047. See also

References

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Winnie The Pooh, 1926. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

||||||||||||||||||||