|

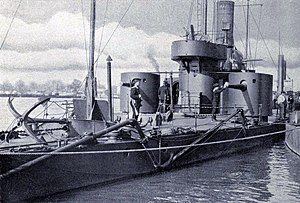

Yugoslav monitor Sava

The Yugoslav monitor Sava is a Temes-class river monitor that was built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy as SMS Bodrog. She fired the first shots of World War I just after 01:00 on 29 July 1914, when she and two other monitors shelled Serbian defences near Belgrade. She was part of the Danube Flotilla, and fought the Serbian and Romanian armies from Belgrade to the mouth of the Danube. In the closing stages of the war, she was the last monitor to withdraw towards Budapest, but was captured by the Serbs when she grounded on a sandbank downstream from Belgrade. After the war, she was transferred to the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), and renamed Sava. She remained in service throughout the interwar period, although budget restrictions meant she was not always in full commission. During the German-led Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, Sava served with the 1st Monitor Division. Along with her fellow monitor Vardar, she laid mines in the Danube near the Romanian border during the first few days of the invasion. The two monitors fought off several attacks by the Luftwaffe, but were forced to withdraw to Belgrade. Due to high river levels and low bridges, navigation was difficult, and Sava was scuttled on 11 April. Some of her crew tried to escape cross-country towards the southern Adriatic coast, but all were captured prior to the Yugoslav surrender. The vessel was later raised by the navy of the Axis puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia and continued to serve as Sava until the night of 8 September 1944 when she was again scuttled. Following World War II, Sava was raised once again, and was refurbished to serve in the Yugoslav Navy from 1952 to 1962. She was then transferred to a state-owned company that was eventually privatised. In 2005, the government of Serbia granted her limited heritage protection after citizens demanded that she be preserved as a floating museum, but little else was done to restore her at the time. In 2015, the Serbian Ministry of Defence and Belgrade's Military Museum acquired the ship. She was restored by early 2019 and opened as a floating museum in November 2021. Description and constructionA Temes-class river monitor, the ship was built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy by H. Schönichen, and designed by Austrian naval architect Josef Thiel. Originally named SMS Bodrog, she was laid down at Neupest on 14 February 1903.[1] Like her sister ship SMS Temes, she had an overall length of 52.6 m (172 ft 7 in),[a] a beam of 9.5 m (31 ft 2 in), and a normal draught of 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in).[3] Her standard displacement was 440 tonnes (430 long tons) with a full load displacement of 484.1 tonnes (476.5 long tons), and her crew consisted of between 77 and 79 officers and enlisted men.[3][b] Bodrog had two triple-expansion steam engines, each driving a single propeller shaft. Steam was provided by two Yarrow water-tube boilers, and her engines were rated at 1,400 indicated horsepower (1,000 kW). As designed, she had a maximum speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph),[2][3] and carried 62 tonnes (61 long tons) of coal.[4] Bodrog was armed with two 120 mm (4.7 in)L/35[c] guns in single gun turrets.[1][3] These were positioned forward on either side of the conning tower, which greatly reduced their firing arcs from the gun arrangement on previous Austro-Hungarian river monitors.[3] She also mounted a single 120 mm (4.7 in)L/10 howitzer in a central pivot mount,[1] positioned aft, but it was a far less effective weapon than the forward guns.[3][5] The maximum range of her Škoda 120 mm guns was 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), and her howitzer could fire its 20 kg (44 lb) shells a maximum of 6.2 km (3.9 mi).[6] Her armour consisted of a belt ranging from 40 mm (1.6 in) to 10 mm (0.39 in) in thickness, casemates and gun turrets 40 mm (1.6 in) to 70 mm (2.8 in) thick, and deck armour 19 mm (0.75 in) thick. The armour on her conning tower was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick.[3][d] Her armour, made of iron–nickel alloy, was an improvement on that of earlier Austro-Hungarian river monitors.[3] Bodrog was launched on 12 April 1904, commissioned on 2 August 1904,[1] and completed on 10 November 1904.[2] CareerWorld War ISerbian campaignBodrog was part of the Danube Flotilla, and at the start of World War I she was based in Zemun, just upstream from Belgrade on the Danube,[7] under the command of Linienschiffsleutnant[e] (LSL) Paul Ekl.[1] She shared the base with three other monitors and three patrol boats.[7] Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914, and a little after 01:00 on the following day, Bodrog and two other monitors fired the first shots of the war against Serb fortifications on the Zemun–Belgrade railway bridge over the Sava river and on Topčider Hill.[9] The Serbs were outgunned by the monitors, and by August began to receive assistance from the Russians. This support included the supply and emplacement of naval guns and the establishment of river obstacles and mines.[10] On 8 September, the Austro-Hungarian base at Zemun was evacuated in the face of a Serbian counterattack.[11] Bodrog and the minesweeper Andor conducted a deception operation towards Pančevo on 19 September, and six days later, Bodrog bombarded Serb positions on the bank of the Sava near Belgrade. On 28 September, she rendezvoused with the monitor SMS Szamos at Banovci, and the following day the two monitors targeted the Belgrade Fortress and conducted a reconnaissance of Zemun. On 1 October, Bodrog sailed to Budapest, where she was placed in dry dock for two weeks. She returned to the flotilla on 15 October.[1] By November, French artillery support had arrived in Belgrade, endangering the monitor's anchorage,[12] and on 12 November, Ekl was replaced by LSL Olaf Wulff. The stalemate continued until the following month, when the Serbs evacuated Belgrade in the face of an Austro-Hungarian assault.[13] On 1 December, Bodrog and the newly commissioned monitor SMS Enns engaged the retreating Serbs.[1] After less than two weeks, the Austro-Hungarians retreated from Belgrade, and it was soon recaptured by the Serbs with Russian and French support. Bodrog continued in action against Serbia and her allies at Belgrade until December, when her base was withdrawn to Petrovaradin, near Novi Sad, for the winter.[13] The Germans and Austro-Hungarians wanted to transport munitions down the Danube to the Ottoman Empire, so on 24 December 1914, Bodrog and the minesweeper Almos escorted the steamer Trinitas loaded with munitions, the patrol boat b and two tugs from Zemun pas Belgrade towards the Iron Gates gorge on the Serbian–Romanian border.[1][14] The convoy ran the gauntlet of the Belgrade defences unharmed, but when it reached Smederevo it received information that the Russians had established a minefield and log barrier just south of the Iron Gates. It turned back under heavy fire, and withdrew as far as Pančevo without serious damage to any vessel. Bodrog returned to base, and the monitor SMS Inn was sent to guard the munitions and escort the convoy back to Petrovaradin.[14] In January 1915, British artillery arrived in Belgrade, further bolstering its defences,[15] and Bodrog spent the first months of the year at Zemun. On 23 February, LSL Kosimus Böhm took command. On 1 March, Bodrog and several other vessels including the monitor SMS Körös were relocated to Petrovaradin.[1] After the commencement of the Gallipoli campaign, munitions supply to the Ottomans became critical, so another attempt was planned. On 30 March, the steamer Belgrad left Zemun, escorted by Bodrog and Enns. The convoy was undetected as it sailed passed Belgrade at night during a storm, but after the monitors returned to base, Belgrad struck a mine near Vinča, and after coming under heavy artillery fire, exploded near Ritopek.[14] On 22 April 1915, a British picket boat that had been brought overland by rail from Salonika was used to attack the Danube Flotilla anchorage at Zemun, firing two torpedoes without success.[16] In September 1915, the Central Powers were joined by Bulgaria, and the Serbian Army soon faced an overwhelming Austro-Hungarian, German and Bulgarian ground invasion. In early October, the Austro-Hungarian 3rd Army attacked Belgrade, and Bodrog, along with the majority of the flotilla, was heavily engaged in support of crossings near the Belgrade Fortress and the island of Ada Ciganlija.[17]  Romanian campaignFollowing the capture of Belgrade on 11 October and the initial clearance of mines and other obstacles, the flotilla sailed downstream to Orșova near the Hungarian–Romanian border and waited for the lower Danube to be swept for mines. Commencing on 30 October 1915, they escorted a series of munitions convoys down the Danube to Lom where the munitions were transferred to the Bulgarian railway system for shipment to the Ottoman Empire.[18] In November 1915, Bodrog and the other monitors were assembled at Rustschuk, Bulgaria.[18] The Central Powers were aware that the Romanians were negotiating to enter the war on the side of the Entente, so the flotilla established a sheltered base in the Belene Canal to protect the 480-kilometre (300 mi) Danube border between Romania and Bulgaria.[19] During 1915, the 120 mm howitzer on the Bodrog was replaced with a single 66 mm (2.6 in)L/18 gun, and three machine guns were also fitted.[3] When the Romanians entered the war on 27 August 1916, the monitors were again at Rustschuk, and were immediately attacked by three improvised torpedo boats operating out of the Romanian river port of Giurgiu. The torpedoes that were fired missed the monitors but struck a lighter loaded with fuel. Tasked with shelling Giurgiu the following day, the Second Monitor Division, consisting of Bodrog and three other monitors, set fire to oil storage tanks, the railway station and magazines, and sank several Romanian lighters. While the attack was underway, the First Monitor Division escorted supply ships back to the Belene anchorage. Bodrog and her companions then destroyed two Romanian patrol boats and an improvised minelayer on their way back to Belene. This was followed by forays of the Division both east and west of Belene, during which both Turnu Măgurele and Zimnicea were shelled.[20] On 2 October 1916, Bodrog and Körös attacked a Romanian pontoon bridge being established across the Danube at Oryahovo, obtaining five direct hits, thus contributing to the defeat of the Romanian Flămânda Offensive.[1] Bodrog herself received five hits from the Romanian artillery during the engagement and had to retreat behind the Taban Island to repair her damaged turret. News that floating mines were launched by the Romanians forced the monitors to leave and later withdraw to Belene.[21] This was followed by action supporting the crossing of Generalfeldmarschall[f] August von Mackensen's Austro-Hungarian Third Army at Sistow. Bodrog then wintered at Turnu Severin.[1] From 21 February 1917, Bodrog and Körös were deployed as guardships at Brăila. On 1 March, Bodrog became stuck in ice at nearby Măcin. LSL Guido Taschler took command of Bodrog in 1918. That year's spring thaw saw Bodrog, Körös, Szamos, Bosna and several other vessels sent through the mouth of the Danube into the Black Sea as part of Flottenabteilung Wulff (Fleet Division Wulff) under the command of Flottenkapitän (Fleet Captain) Olav Wulff, arriving in Odessa on 12 April. On 15 July, she and Bosna sailed to the port of Nikolaev, and from 5 August, Bodrog was stationed at Cherson. On 12 September, she returned to Brăila along with other vessels.[1] Bodrog was sent to Reni near the mouth of the Danube to protect withdrawing Austro-Hungarian troops, arriving there on 1 October. She then sailed upstream, reaching Rustschuk on 11 October, and Giurgiu two days later. On 14 October, she was deployed at Lom.[23] She was the last Austro-Hungarian monitor to withdraw towards Budapest and was the only one that failed to reach the city. On 31 October 1918, Bodrog collided with a sand bank while navigating through heavy fog near Vinča,[24] and heavy Serbian artillery fire prevented her from being salvaged.[3] She was later captured by the Serbian Army.[25] Interwar period and World War II From the Armistice to September 1919, Bodrog was crewed by sailors of the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Serbo-Croatian: Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, KSCS; later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). Under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Bodrog was transferred to the KSCS along with a range of other vessels, including three other river monitors,[26] but was not officially handed over to the KSCS Navy and renamed Sava until 15 April 1920.[27][28] Her sister ship Temes was transferred to Romania and renamed Ardeal.[2] In 1925–26, Sava was refitted, but by the following year only two of the four river monitors of the KSCS Navy were being retained in full commission at any time.[29] In 1932, the British naval attaché reported that Yugoslav ships were engaging in little gunnery training, and few exercises or manoeuvres, due to reduced budgets.[30] Between 1933 and 1934, a single Vickers QF 2-pounder (40 mm (1.6 in)) L/39 anti-aircraft gun, which had been removed from one of the Hrabri-class submarines during a rebuild, was mounted on Sava to improve her anti-aircraft defences. In 1939, this gun was replaced by a single Škoda 40 mm L/67 anti-aircraft gun.[3] Sava was based at Dubovac when the German-led Axis invasion of Yugoslavia began on 6 April 1941. She was assigned to the 1st Monitor Division,[31] and was responsible for the Romanian border on the Danube, under the operational control of the 3rd Infantry Division Dunavska.[32] Her commander was Poručnik bojnog broda[g] Srećko Rojs.[3] On that day, Sava and her fellow monitor Vardar fought off several attacks by individual Luftwaffe aircraft on their base.[34] Over the next three days, the two monitors laid mines in the Danube near the Romanian border.[35] On 11 April, they were forced to withdraw from Dubovac towards Belgrade.[36] During their withdrawal, they came under repeated attacks by Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers.[37] Sava and her fellow monitor were undamaged, and anchored at the confluence of the Danube and Sava near Belgrade at about 20:00, where they were joined by the Morava. The three captains conferred, and decided to scuttle their vessels due to the high water levels in the rivers and low bridges, which meant there was insufficient clearance for the monitors to navigate freely. The crews of the monitors were then transshipped to two tugboats, but when one of the tugs was passing under a railway bridge, charges on the bridge accidentally exploded and the bridge fell onto the tug. Of the 110 officers and men aboard the vessel, 95 were killed.[36][38] After the scuttling of the monitors, around 450 officers and men from the Sava and various other riverine vessels gathered at Obrenovac. Armed only with personal weapons and some machine guns stripped from the scuttled vessels, the crews started towards the Bay of Kotor in the southern Adriatic in two groups. The smaller of the two groups reached its objective, but the larger group only made it as far as Sarajevo by 14 April before they were obliged to surrender.[39] The remainder made their way to the Bay of Kotor, which was captured by the Italian XVII Corps on 17 April.[40] Sava was raised and repaired by the navy of the Axis puppet state the Independent State of Croatia,[38] at the railway rolling stock factory at Slavonski Brod,[3] and served alongside her fellow monitor Morava, which was also raised, repaired, and was renamed Bosna. Along with six captured motorboats and ten auxiliary vessels, they made up the riverine police force of the Croatian state.[41] Sava was part of the 1st Patrol Group of the River Flotilla Command, headquartered at Zemun,[42] and was commanded by Kapetan korvete[h] Stjepan Lerner.[3] In Croatian service, Sava was armed with two 120 mm guns, one 40 mm anti-aircraft gun, one Zbrojovka Brno 15 mm (0.59 in) ZB-60 anti-aircraft machine gun, two light machine guns, and two mine throwers.[3] Her crew scuttled her near Slavonski Brod on the night of 8 September 1944 and defected to the Yugoslav Partisans.[43] Post-war period Sava was again raised and refurbished after World War II. Armed with two single 105 mm (4.1 in) gun turrets, three single 40 mm (1.6 in) gun mounts and six 20 mm (0.79 in) weapons,[44] she served in the Yugoslav Navy from 1952 to 1962. Afterwards, she was placed into the hands of a state-owned company, which was privatised after the breakup of Yugoslavia. In 2005, the government of Serbia granted her limited heritage protection after citizens demanded that she be preserved as a floating museum, though little else had been done to restore her as of 2014, by which time she was serving as a gravel barge.[24] In December 2015, Sava was acquired by the Serbian Ministry of Defence and Belgrade's Military Museum, which planned on restoring her.[45] The ship is one of only two surviving Austro-Hungarian river monitors that served during World War I.[46] The other is SMS Leitha, a much older monitor, which has been a museum ship anchored alongside the Hungarian Parliament Building in Budapest since 2014.[47] By early 2019, Sava had been restored.[48] She was inaugurated as a floating museum along the Sava River in Belgrade in November 2021.[49] Notes

Footnotes

ReferencesBooks and journals

Online sources

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||